Tales of the Talmud: Tragedies and Triumphs

| June 9, 2024The Reading Room at the National Library of Israel (NLI) is home to innumerable sets of Gemaras

The Reading Room at the National Library of Israel (NLI), three soaring stories covered by a massive domed skylight, has been likened to an immense well. The building’s lowest level contains a large, circular shelf designed for oversized books, home to the library’s innumerable sets of Gemaras — our nation’s life source stored there like water deep in the heart of a well.

The Past Is Prologue

After the Churban, when Klal Yisrael began their long exile, our Sages realized that Torah shebe’al peh (oral halachic transmission) was at risk, and halachah needed to be written to avoid getting lost. Rabi Yehuda Hanasi compiled the Mishnah around the year 200; 300 years later, Ravina and Rav Ashi compiled the Talmud.

Few handwritten manuscripts remain, for various reasons. For starters, Gemaras weren’t written for display; rather they were designed for daily use. A town might have only a few masechtos, shared by all, and however durable the parchment, constant use took its toll.

Another — tragic — reason we have few surviving copies: the Talmud was viewed as an existential threat to the reigning church. Christian leadership would frequently stage biased “debates” and “trials” of the Talmud, designed to prove which religion was the truth, and most, if not all, copies of the Talmud would be destroyed or heavily censored.

Photos: Bavarian State Library, the National Library of Israel.

“Ktiv” Project, the National Library of Israel

The Lone Survivor

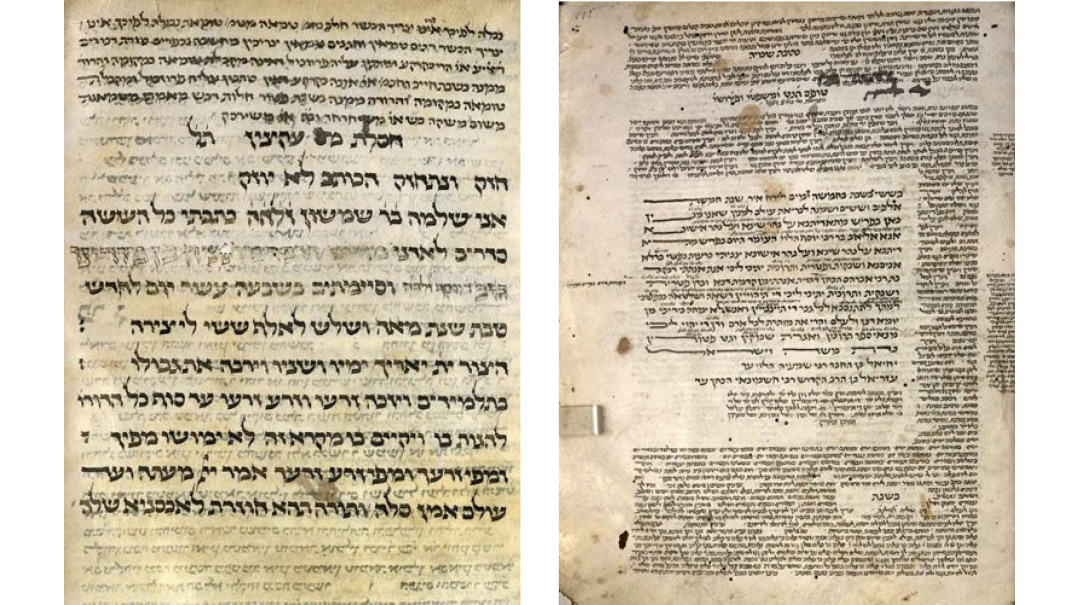

Munich 95 | 1342

There is one known complete handwritten Talmud, a rare miracle with the unassuming name: Munich 95, named for a cataloging term at the Bavarian State Library, its current home.

Written in 1342 by the sofer Shlomo ben Shimshon (who often decorated the name Shlomo when it appeared in the text), this colossal, handwritten work is comprised of 577 painstakingly detailed pages, with all 37 tractates of the Talmud text written in smaller print around the Mishnah being discussed, 62 tractates of Mishnah in all. It also contains various baraisas, a section with 40 halachic contract samples, and even poetry; an anthology of Torah in one leatherbound edition.

This safrus marvel is crafted on the thinnest parchment, likely from newborn goat’s skin, with microscopic lettering measuring one-and-a-half millimeters high (compare that to Times New Roman size 12 font, which is over 3 millimeters high), legible due to the invention of glasses in Italy several decades earlier.

The 14th century was a dangerous time for the French Jews, who suffered expulsions, forced conversions, and other atrocities. The Chief Rabbi of Paris, Yochanan ben Mattisyahu, owned the Munich 95, but the church confiscated it and imprisoned him under the charges of using the Talmud to spread anti-Christian ideas. Despite the danger, Rav Yochanan wrote letters from his prison cell, urging others to create more copies of the Talmud to replace those that were destroyed. He was eventually released from prison after he paid 3,000 florins and agreed to erase anything “anti-Christian” from the Talmud. Close examination of the Munich 95 manuscript does reveal some erased lines, but Rav Yochanan’s defense allowed this copy to survive for centuries.

While the NLI doesn’t have the physical Munich 95 print, it does have online access and a facsimile.

Start The Presses!

Guadalajara Talmud | 1482

In 1440, Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, a former goldsmith and gem cutter, invented something more powerful and potentially more precious than the gold and jewels he once worked with: the Gutenberg printing press. The world of books — indeed, the world as a whole — would never be the same.

The Jewish world changed drastically, as well. Before the creation of the printing press, writing a sefer was laborious, time-consuming, and costly. As printing quickly spread, hundreds of printers mass-produced books, making them cheaper and more accessible. However, few sets of the Talmud were printed initially, as publishers were wary of printing a long-persecuted book.

In 1482, Guadalajara, Spain, saw the first printed masechtos of Gemara. This early printing was short-lived; ten years later, during the Spanish expulsion, most copies were lost or destroyed.

Building The Foundation

Soncino Gemaras | 1484

When printing in Spain came to a tragic close, Italy took up the mantle. In the 15th century, a German Jewish family settled in Soncino, Italy, following an expulsion. Adopting their new hometown as their last name, the Soncino family became involved with moneylending, a Jewish field due to the church’s ban on interest. With time, Italy allowed non-Jewish banks to open. The Soncinos lost their business, but their next venture, Soncino Press, would make them famous.

Soncino Press’s first work, Talmud Bavli Maseches Berachos, was printed in in 1484, with an innovative format that placed Mishnah and Gemara in the center of the page with Rashi’s commentary on the inside and Tosafos on the outside. Sound familiar? This layout resembles tzuras hadaf, standard on every Gemara page today. The Soncino Press printed about 20 masechtos and numerous other seforim, including the first complete Hebrew Tanach with nekudos. The Soncino Gemaras were also illustrated, which slowed the printing process, so they never printed a complete set.

The Merchant Of Venice

Bomberg Talmud | 1523

The 16th century saw Venice become a printing center for everyone but the Jews, who were forbidden from owning a press. Daniel Bomberg, a non-Jewish printer, decided to print the entire Talmud, and he sought permission from Catholic Pope Leo X for his ambitious project. In 1518, Pope Leo granted him the privilege —with one horrifying condition: that a Jewish apostate, a convert to Catholicism, write notes in the Talmud’s margins whenever it contradicted or condemned Christianity. The Talmud, Judaism’s defining work, was now at risk of becoming a platform for its greatest adversary.

However, in a remarkable turnaround, Pope Leo reversed his order in 1519. No reason was ever given, but his inexplicable change of heart allowed Bomberg to compile and print the fully uncensored Talmud without Christian interference. Furthermore, Bomberg was even permitted to assemble a committee of scholars, including Jewish rabbanim and dayanim, to assist in the formidable task of compiling the entire Talmud —the first complete printed set of Talmud.

The Bomberg Talmud popularized the tzuras hadaf established by Soncino, becoming the Talmud publishing standard for all time. Equally important, it added another crucial innovation: page numbers. While it seems obvious today for any work, especially a long one, in the early days of printing, pagination was rare. By placing standardized page numbers in every volume of the Talmud, Bomberg made it possible for Jewish scholars everywhere to literally be on the same page when studying or writing about the Talmud.

The Bomberg Talmud, all 63 masechtos, was completed in 1523. Pope Leo’s change of heart, Bomberg’s professionalism, the Jewish scholars of the time, and the concept of standardized pagination all made possible, exactly 400 years later, Rav Meir Shapiro’s brilliant Daf Yomi innovation.

With the Soncino and Bomberg publications, the future of Jewish publishing seemed to be in Italy —until August 1553, when two non-Jewish publishers, embroiled in a fierce dispute over what we’d today call intellectual property rights over some seforim, appealed to the church and denounced each other for printing “heretical” works. The Italian Church ruled that all copies of the Talmud must be seized and burned, and further Jewish printing was banned.

In Rome, Bologna, and Venice, Inquisitors ruthlessly invaded Jewish homes and synagogues, seizing any Hebrew or Aramaic texts and incinerating them in massive bonfires. This marked the end of Italy as the epicenter of Jewish learning and publishing, and for the next 200 years, small presses in cities like Krakow, Prague, and Lublin printed some masechtos.

From Venice to Vilna

The Vilna Shas | 1834

Romm Press, a small printing shop established by Boruch Romm in 1788 in Grodno, focused on publishing Hebrew books, particularly halachic seforim. The family relocated to Vilna, and the business was passed down through generations until David Romm took the helm. Tragically, David died suddenly, leaving his wife Devorah a 29-year-old widow with seven children, giving her as well a share in the business he and his two young brothers had owned — a printing press with a vision to publish the whole Talmud as it had never been published before.

The process did not go smoothly. Interference from the Russian government, edicts from the Polish government banning Jewish book sales, economic woes, competition, lawsuits from other printers, and a factory fire all hampered progress, but “The Almanah and the Brothers Romm Press” persevered.

Over 100 printers and 14 proofreaders spent 20 years on the project, meticulously editing, proofreading, correcting errors from prior editions. “The Almanah,” Devorah Romm, a savvy businesswoman, upgraded the printing press with new equipment, including lead plates, and was personally responsible for securing permission to send scholars to study Rabbeinu Chananel’s works in the Vatican, a crucial addition. However, when her team arrived, they found the Vatican closed for a four-month vacation, jeopardizing Romm Press’s deadline and endangering the whole project. Devorah managed to obtain special access, ensuring the project’s continuation.

In 1834, Romm Press printed their first edition of the Vilna Shas, featuring 40 new commentaries and a font now commonly used in Talmud.

Like many European Jewish institutions, the Romm printing dynasty met a tragic end. After Devorah Romm’s death, ownership changed multiple times, until its final owner, Mathus Rapoport, was murdered by Nazis. (Legend tells of Jewish partisans who raided the press building and used Devorah’s lead plates to craft bullets against the Nazis.) During the Cold War, the press was seized and shut down by the Russians. After more than 150 years, the Romm printing legacy ceased, yet their meticulously crafted Talmud remains a global standard.

Photos: Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The Talmud Goes to War

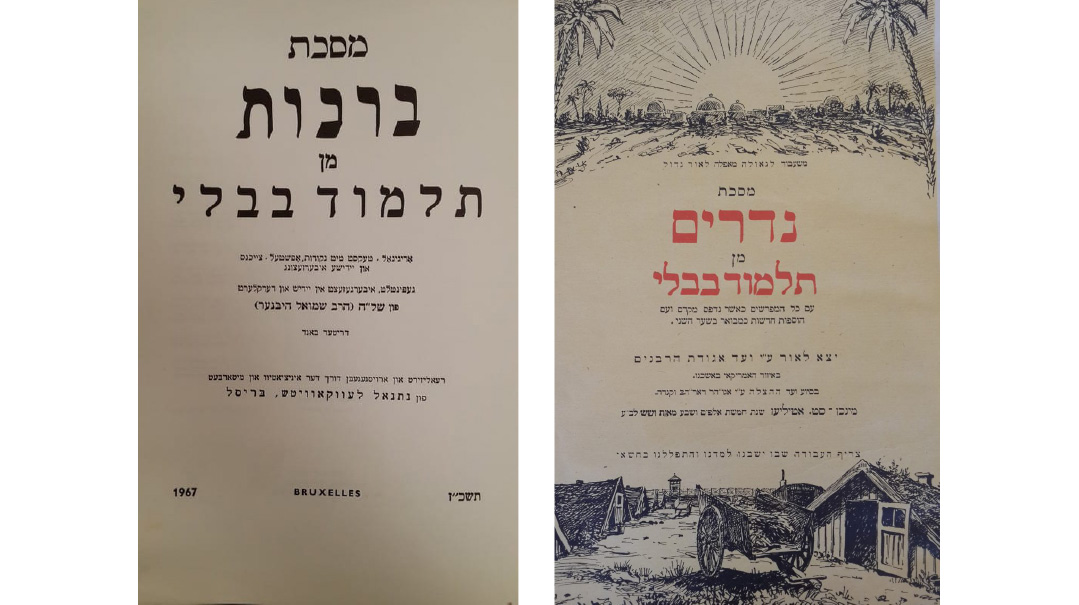

Yiddish Gemara | 1942

Survivors’ Talmud | 1946

In Nazi-occupied Brussels, askan Netanel Lefkowitz recognized the Nazis’ aim to destroy Jews physically and spiritually, but he foresaw their defeat as well. In his desire to make the Talmud more accessible when the Jewish nation would rebuild after the war, he convinced Rabbi Shmuel Hibner, a talmid chacham, to translate masechtos into Yiddish and add nekudos. Rabbi Hibner hand-wrote a Yiddish translation of three masechtos while hiding from the Nazis in an attic.

After the war, Rabbi Lefkowitz printed some translations. Years later, he presented a copy to Israeli President Yitzchak Ben-Zvi, including a dedication in which he wrote how the Talmud was written “at the time that the powers of darkness wanted to annihilate our People and our Torah.”

Elsewhere, Dachau survivors were sent to a hospital building in the German monastery St. Ottilien after the war. Staffed by Jewish survivors, more than 400 children were born there in the next three years, a wondrous sign of Jewish renewal.

A German printer from a nearby monastery brought the survivors a treasure: a volume of a Vilna Shas, mesachtos Nedarim and Kiddushin. Camp rabbanim carefully took the sefer apart page by page to allow more people to learn the dapim. Survivors from all over the area streamed to the monastery when they heard about the Talmud shiurim.

It was only one Gemara, but it was a start. Two of the camp rabbanim, Rabbis Shmuel Yaakov Roz and Shmuel Abba Snieg, worked with the German printer to make 10,000 copies of the two masechtos and distribute them throughout Europe, a project sponsored by the Vaad Hatzalah in America.

A young survivor created the extraordinary cover page for the Talmud. On the bottom, he drew his memory of Dachau: a watchtower, barbed wire, and a straw-covered wagon. On top, the visualization of his dream of Yerushalayim: palm trees, a rising sun, and domed buildings. Two pesukim from Tehillim tell the whole story: next to Dachau, the pasuk “They almost destroyed me on Earth, but I didn’t abandon Your teachings,” and next to Yerushalayim, “From slavery to redemption, from darkness to great light.”

Braced by the overwhelming response to their printing, Rabbis Snieg and Roz recognized the overwhelming need for full sets of Gemaras on European soil. They conceived an ambitious plan: to print full Talmudic sets with the assistance of the US Army.

Their initial challenge highlighted how crucial their project was: post-war Europe lacked a single complete set of the Talmud to use for reference, and they could begin only once two sets arrived from the US. After many bureaucratic hurdles and delays, what is now known as the Survivors’ Talmud began printing in 1950. The cover page of this Talmud mirrored the St. Ottilien edition, with minor adjustments. Artist G. Rosenkranz signed his name and included thanks to the Vaad Rabbonim of Germany, the Joint, and the US Army. He also added a haunting depiction from Dachau: two inmates loading bodies onto the straw-covered wagon.

The dedication in the Survivors’ Talmud thanks the United States Army: The army played a major role in the rescue of the Jewish people from total annihilation and after the defeat of Hitler bore the major burden of sustaining the DPs of the Jewish faith. This special edition of the Talmud…will remain a symbol of the indestructibility of the Torah… (Signed) Rabbi Samuel A. Snieg, Chief Rabbi of the US Zone.

Even in the Darkness

Schottenstein Talmud

Within a week of the October 7th massacre, Artscroll/Mesorah, publishers of the Schottenstein Talmud, printed 20,000 copies of the second half of Maseches Kiddushin so Israeli soldiers heading to battle could continue learning Daf Yomi. As the war sadly stretches on, Artscroll has continued distributing subsequent Daf Yomi masechtos. These lightweight editions also include chapters of Tehillim, Mi Shebeirach for soldiers, and Tefillas Haderech.

The National Library created an archive for material connected to October 7 and its aftermath to help future scholars understand the pain — and the pride — of these difficult days. These specially printed Daf Yomi Talmud editions form an important part of the story.

In a few weeks, Daf Yomi will begin Maseches Bava Basra. ArtScroll has already printed thousands of copies, but who knows? Will our soldiers learn these copies of the daf quietly in their homes or yeshivahs, or will they still be in armored vehicles amidst the dusty ruins of Gazan homes, learning in the lull between fierce battles?

The future is uncertain, but one thing is sure: The Talmud’s words, passed down since Matan Torah, have defined us through our toughest times. They will remain, forever, the eternal treasure of Hashem’s eternal people.

Thanks to the National Library of Israel for their help in researching this article.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1015)

Oops! We could not locate your form.