Tales for the Child Within

Their stories of tzaddikim captured shtetls of the past and values for eternity

Photos: Ariel Ohana; Family archives

They’re the stories we grew up on, tales of the shtetl, of evil poritzes and righteous innkeepers, of greedy farmers and wagon wheels stuck in the mud. While the 120 iconic blue books with the Sippurei Tzaddikim label were the brainchild of Rabbi Gershon and Peninah Burkis and encouraged by their rebbe, they never dreamed that little project would still be entertaining a second generation of children 45 years later

Rabbi Gershon and Mrs. Peninah Burkis were happy about the phone call but not really surprised — they knew it all along.

On the line was an effervescent Lelover chassid who had just returned from a visit to Poland. “I visited the town of Lelov in Poland last week,” he told them excitedly, “and you won’t believe it, I actually saw the wagon that was mired in the mud, from the Machanayim book about the Lelover Rebbe that I read as a kid! And we also saw the wagon driver and the farmers. Everything was just like in the pictures of your books. All of us in the group remembered the Machanayim/ Sippurei Tzaddikim stories we read as children.”

Rabbi Burkis wasn’t sure if this man in his forties was totally serious, but one thing was clear: The fellow knew the story by heart and could quote it word for word. He also remembered every illustration and even the color of the kasket each child wore.

And he’s not the only one. Many of us feel sparks of nostalgia just looking at those soft-cover blue books with the yellow arch framing a memorable picture: titles like The Brave Butcher, Saved by the Wedding, Wonder Rooster, The Wagon that Sank, Poisoned Bread, The Man Who Flew in the Air, and Mystery of the Sundial are just a few of the 120 stories that take us back to the poritzes and taverns, to the clumsy farmers, to the muddy wagon drivers, to tales of faith in the shtetl, stories that framed our childhood.

While the books are already entertaining a second generation of children in Hebrew, English, and several other languages, Reb Gershon and his wife Peninah are still amazed that they were tasked with creating such enduring and inspirational narratives for young readers. It was certainly not on their radar when they moved to the northern Israeli development town of Migdal Ha’emek in the early 1970s as Chabad emissaries, one of just a few religious couples together with Rav Yitzchak Dovid Grossman, who had not yet been officially appointed as the city’s rav. But it wasn’t their place to ask questions: They were given a mission by their rebbe and never looked back.

Rabbi Gershon Burkis never expected to become a publisher, but two generations later, he can’t deny he was onto something

R

omanian-born Reb Gershon was three years old in 1950 when his family made aliyah to the northern Haifa suburb of Tirat HaCarmel. (During the 1950s, Romania was the only Communist country not to break diplomatic relations with Israel, allowing a limited number of Jews to emigrate to Israel in exchange for much-needed Israeli agricultural and industrial aid.) Gershon studied in a state religious school, but as his Yiddishkeit grew stronger, he switched to a Chabad yeshivah and didn’t hesitate when he was offered a ticket to America to learn in the court of the Lubavitcher Rebbe zy”a.

The group was there from Erev Pesach of 1967 until the summer of 1968, during which time Reb Gershon honed his passion: collecting sippurei tzaddikim and verifying and corroborating the sources and details for accuracy and authenticity. The stories fascinated him.

After spending a year in New York, Reb Gershon returned to Israel, and a short time later, a shidduch was suggested with Peninah, whose family had made aliyah from Romania a short time before. By that time, Romanian dictator Ceaușescu, in a move aimed at maintaining economic independence from the Soviet Union, decided to exchange Jews for cash from Israel, and for the next two decades until the fall of the Iron Curtain, Romania was granting exit visas for about 1,500 Jews a year in exchange for cash and military equipment.

“We always dreamed of moving to Eretz Yisrael,” Mrs. Burkis relates. “But it wasn’t easy to get on the list. I remember that we were forced to go to school on Shabbos, and we knew that if we didn’t go our parents would be imprisoned. The teachers would harass us, intentionally scheduling tests for Shabbos.”

One Shabbos she came home from school to find the house surrounded by a crowd of Jews. In the middle were several police officers who were threatening to take her father away. She soon learned that the police had finally come with the coveted exit visas and insisted her father sign the documents so that the family would be able to leave two weeks later. “My father refused to desecrate Shabbos,” Mrs. Burkis relates. “In the end, the police left empty-handed, but we had great siyata d’Shmaya, and somehow the documents were arranged. Two weeks later we boarded the plane to Eretz Yisrael.”

Peninah’s parents settled in the Haifa suburb of Kiryat Ata and sent their only daughter to study in “Wolf Seminary” in Bnei Brak. After completing high school and seminary, she taught in nearby Kfar Chassidim, and once she and Gershon married, they decided to buy an apartment in Migdal Ha’emek and together with Rav Grossman, strengthen the residents of the small town.

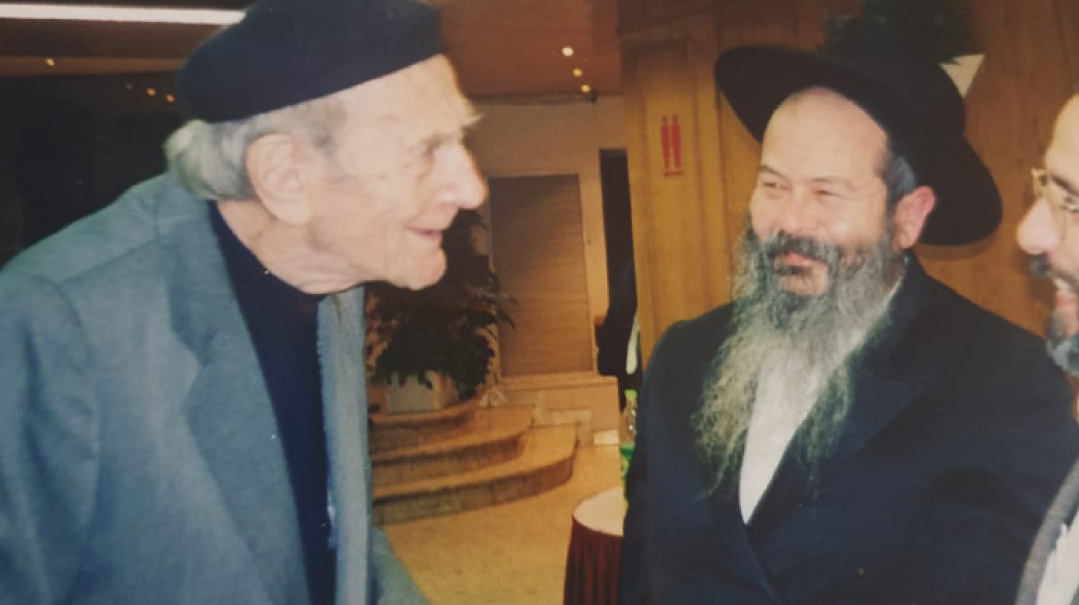

Rabbi Burkis visited Tel Aviv Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau in his home, where they discussed the importance of providing children with quality Jewish reading material. Rabbi Burkis also presented Rabbi Lau with some of Machanayim’s newest titles, printed after a hiatus of 20 years

IN 1977, the Burkises moved to the town of Lod, where Rabbi Burkis served as a member of the city’s religious council while Peninah was teaching in the state religious school system, both busy with kiruv as their own family began to grow — and those years became the turning point that would touch the lives of children around the world.

“When our oldest son was four and already knew how to read, I was bothered that I didn’t have frum children’s books to give him,” Mrs. Burkis remembers. “So I’d buy general children’s books and draw yarmulkes and tzitzis on the characters, censoring inappropriate messages. My husband would tease me for all the effort, and at one point I answered him, ‘How about if you publish books that will be more appropriate for our children?’ I didn’t really mean that he should actually do it. I didn’t think in that direction at all. I was a teacher, and he was an avreich who learned with people in the community. What did we know about publishing?”

That summer, the two traveled to the Lubavitcher Rebbe in New York, and before their yechidus with the Rebbe, they submitted a note with several chinuch questions, as well as mentioning that they wanted to publish books for children in the authentic spirit of Yiddishkeit, stories that would convey the values of middos tovos, yiras Shamayim and emunas chachamim.

“I looked at what my husband wrote and was really shocked,” says Mrs. Burkis. “True, we’d thrown out the idea of publishing Jewish books for children, but it was totally impractical. Why did my husband go into such detail about it in his note to the Rebbe? But my husband didn’t give in, and in the end, we were very surprised because for nearly half the yechidus, the Rebbe spoke to us specifically about this topic.”

The Rebbe’s answer became their mission statement. “Regarding what you wrote about publishing illustrated books for children, this is very, very important. Do it with a good artist, print them on the highest quality paper, and make sure the stories will be acceptable to all streams [of religious Jews].”

The Rebbe also made an astute political analysis: That year, there was a regime change in Israel, with the Likud and traditionalists rising to power. The Rebbe mentioned that for the first time ever, the Education and Culture ministry was being given to a religious minister (Zevulun Hammer of the National Religious Party), and that perhaps they should try to partner with consultants in the ministry who would be interested in this new angle of children’s literature.

“We left the room quite stunned,” Mrs. Burkis says. “We understood that we had been tasked with a difficult mission. The Rebbe’s secretary saw how lost we must have looked, asked us what the Rebbe told us, and promised that he and other chassidim would be at our service.”

“And that’s what happened,” says Reb Gershon. We worked out the basic ideas for the Machayanim books with some askanim in New York before returning to Israel.

“We sat with them and they guided us toward stories, some of them stories of Chazal and others chassidic tales, which we would work through and turn into children’s books.”

The Rebbe’s encouragement and guidance became the stunned couple’s mission statement

T

he couple returned to Israel with a huge task on their shoulders: to publish quality books for children. They also knew it would include research, writing, artwork, and distribution. And so they first decided to produce a series of coloring books — the first one on the subject of Shabbos candles, another one about doing good deeds. Several others followed.

Meanwhile, Reb Gershon began to move the book project forward. “I’ve always loved stories of Chazal, stories of emunas chachamim, stories about Jewish wisdom and authentic Jewish heroism,” he says. “In any encounter, I’m always trying to fish out a good story and file it away, so I started by collecting stories from the Gemara, stories of Chazal, stories of the Baal Shem Tov and his talmidim. Once we had a story, the next step was to bring it down to the level of understanding of young children. My wife worked on the content, and then we gave it over to a writer. The first six books were written by Bella Golombowitz a”h and afterward, by Bracha Knoblowitz.

“Initially,” he continues, “I looked for stories that had an emphasis on children, because I assumed that stories where children played a significant role would better capture the interest of the children of our generation. Another thing I kept in mind is that every story should have a lesson for young readers.”

And perhaps most challenging, Reb Gershon always took great pains to confirm the veracity of every detail in the story and to stick to the sources.

“Finding stories isn’t the hard part,” Reb Gershon says. “Chazal and our seforim are rich with stories, but the real difficulty is clarifying the exact details, because it was important for us to adhere to the sources. And if we couldn’t find the source, then we’d simply table the story.

“I’m a real stickler for authenticity and detail, but as time passed, I realized the great responsibility we carried and that people rely on the details in our stories and use them in their own lives. For example, someone told me that in one shul, the gabbai banged on the bimah and announced that ‘Tomorrow, 29 Tammuz, is Rashi’s yahrtzeit,’ and when the mispallelim raised an eyebrow, he added, ‘that’s what it says in the Machanayim book.’ ”

Once the authenticated stories were in place, they had to tackle a completely different angle, which both old and young readers are grateful for until this day: illustration.

They remembered the Rebbe’s instructions — to hire the best artist whose drawings would touch the hearts of children — but how would they find him?

Mrs. Burkis began scanning the children’s sections of bookstores, flipped through pages, examined the illustrations, compared artists, and then came across the series called Temunos Mesapros, published by Yavneh. She liked the drawings; the faces were drawn with a certain chein, a purity and feeling of yiras Shamayim. On the cover flap appeared the name of the artist: Chaim Henryk Hechtkopf.

“I immediately connected to the work, and I decided right away that he was going to be our artist,” Mrs. Burkis recalls. “I bought two books from the series, and when I returned home, I tried hunting him down through directory assistance. There was no such name in Jerusalem or Tel Aviv, but after a search, the very accommodating operator told me, ‘There is a children’s book illustrator in Bat Yam by the name of C. Hechtkopf.’ I tried the number, which was answered by an elderly gentleman in very flowery, Biblical-style Hebrew. When I explained what we wanted, he responded, ‘Indeed, you have come to the right place. I am at your service. When would you like to meet?’ So we set up a meeting and we got to know a truly exceptional person.”

Chaim (Henryk) Hechtkopf was born in Warsaw in 1910 to a religious Polish Jewish family. He studied in the Hebrew Gymnasium and then obtained a law degree from Warsaw University, following which he became the first Jewish jurist to petition in the Polish Supreme Court.

He was also an accomplished artist and worked in film animation. And despite his secular education, much of his work was laced with religious symbolism and Jewish life from his shtetl background. During World War II, he retreated with the Polish army east into the Soviet Union, where he was captured and sent to work in a series of forced labor camps. After the war, he returned to Poland to find that his whole family had been massacred — and his work in the decades following had a distinct Holocaust motif.

After the war, he moved back to Lodz, where he helped establish a Jewish artists’ society and taught film. He left Poland for Israel together with his wife in 1957 and settled in Bat Yam, where he remained for the rest of his life, working as a painter and illustrator of books.

When the Burkises first met the artist, he was concerned: He was intrigued by their product, but wondered whether he was suitable, as up to then, he’d been illustrating books for secular Israelis.

“Although he was no longer religious — he left it all after his entire family was massacred in the Holocaust — he grew up in a religious home, was a next-door neighbor to the Imrei Emes of Gur, and descended from holy forbears. It was obvious that he had a high neshamah,” Reb Gershon says. “He was a descendant of Rav Pinchas of Koritz and was a scion of families of gedolei Torah and giants of the spirit. And because he was familiar with the shtetl and it still had a special place for him, he was able to bring its energy and authenticity out in his drawings, even in their seeming simplicity.”

Hechtkopf, who had no children and who would become widowed during the time he put his stamp on Machanayim, eventually became an honorary member of the Burkis family until his passing in 2004 at age 94.

“We were not Hechtkopf’s only customers,” Reb Gershon stresses. “He was an accomplished artist whose paintings fetched a fortune, but he told me once, ‘I don’t just make random drawings for Machanayim, I am drawing my life… The only Jew who will remain eternal is the chareidi Jew, and that’s why I prefer to invest all that I have into these chareidi children, who are the future of our people.’

“I visited Hechtkopf at home when he was 94,” Reb Gershon recalls. “He had lost his sight, and he had become pensive and even otherworldly. Suddenly he said to me, ‘I feel like this year I will be leaving this world.’ When I asked him why he thought so, he replied, ‘My righteous grandmother, who was from the Soloveichik family, died at age 94. She blessed me with arichus yamim a short time before her passing. Now I think that her brachah has been fulfilled.’ Indeed, he passed away peacefully on an Erev Shabbos a few weeks later.”

T

he first book in the soon-to-be iconic series was The Power of Tehillim, about how the Tehillim of a few innocent children saved their father from death at the hands of a cruel poritz. “This story appears in a collection of letters of the Rebbe Rayatz of Lubavitch zy”a, who lived during one of the most difficult periods of persecution for Klal Yisrael in Russia,” Reb Gershon explains. It’s the story about a family of children anxiously waiting for their father to return home. They’re surprised by a visit from the Rebbe Maharash of Lubavitch, who suggests that they read pesukim from Tehillim. After their father returns, he tells them how the wicked non-Jew tied him up and planned on killing him, but each perek of Tehillim removed him from another level of danger, until he was able to escape and return home.

“When I think about it, I don’t know how I was able to do it,” Reb Gerson relates, “because I still made sure to maintain my learning schedule, and I did all these trips between sedorim. I schlepped huge packages of valuable illustrations and print plates. There were no shortcuts, because there was no email and we couldn’t use a delivery service.”

“Machanayim” sounds like the name of a big publishing house, but really it was just the acronym of a help organization for new immigrants run by his friend whose telephone number was listed on the operation.

“And there’s another meaning to Machanayim, which is more relevant now than ever,” Mrs. Burkis adds. “If we think about the word, it expresses everyone’s machaneh, the camp of all of Klal Yisrael, and our books really are not intended for one chassidus or another. They really are written for all of Am Yisrael.” At least 20 of the books are stories of Sephardic gedolim or with settings in eastern countries.

Anyone who is familiar with the little blue books has surely read the back cover, with a listing of all 120 titles published by Machanayim. But is that the end? Why have no new titles been published in the last 20 years?

“We have at least 30 more books that are written and ready,” Mrs. Burkis explains. “But it’s hard to find an illustrator who can replace the charm and chein of Chaim Hechtkopf. And then Covid hit, which was a good time to organize our storage rooms, and to our surprise, we found a series of Hechtkopf’s drawings that had never been published. We’re using them for a new series of Machanayim books about Hillel Hazaken. The first one is called Hillel’s Patience, and another one is written about his pious wife. Two more are slated for release in the near future.”

Because the books were aimed at a wide swath of religious children with varying degrees of cultural sensitivity, there were often complex deliberations about the illustrations. For example, in The Boy Who Saved the Ship, about a ship that was about to sink, all the non-Jews on board took out their idols and prayed to them to help, but they were useless, while the Jewish boy in the corner of the ship prayed to Hashem and was answered right away.

“In this story, Hechtkopf first drew images of idols in the hands of the non-Jews, but we rejected those, because we didn’t want to show those images to young children,” says Reb Gershon. “We deliberated how to illustrate the story, and in the end we asked Rav Moshe Yehuda Leib Landau a”h, the rav of Bnei Brak. He advised us to draw the non-Jews carrying sacks with idols on their backs.

“We also faced a dilemma in the story The Torn Coat, which describes improper behavior of a son towards his father. It is a story told by the Ben Ish Chai in the sefer Nifla’im Maasecha, and the main character is a Jew who did not honor his father appropriately. Generally, when we’d draw the image of a Jew, he’d have a big yarmulke, beard, peyos and tzitzis, but here, the Jew did not behave properly, so we couldn’t have him look like a tzaddik. In the end I think we struck a good balance. Hechtkopf made sure that no matter how bad or misguided, a Jew would never look like one of the thieves, pirates, or the evil poritz.”

Chaim Hechtkopf became an honorary member of the Burkis family. Although no longer religious, he felt it a privilege to recreate the memories of a lost world

IN HIS MIND’S EYE

By Menucha Fuchs

I was familiar with Chaim Hechtkopf from the Machanayim books, but once, back when I was a writer for Mishpacha’s Hebrew magazine, I was asked to interview him in person.

I adored Hechtkopf’s drawings and I was excited to meet him and speak to him about his work. But when I called him to set up an appointment, he refused. “I’m an old man,” he told me. “Why is it important to you what I say?”

I replied that the fact that he was old and wise was actually a good reason to interview him, because he surely had a lot to relate. He appreciated my answer and invited me over. He had so much to say yet so little strength to speak.

In the end I wrote the article, sharing with readers his memories of shtetl life between the two world wars. When the magazine was published, I again traveled to Bat Yam, where he lives, to bring him a copy.

Hechtkopf didn’t let me leave. He told me he had something interesting to show me. He went into the next room, and came out holding huge packages of illustrations. I had no idea how he could even carry them, he was so weak at the time.

It turned out that these were drawings he’d made after arriving in Israel, depicting life of the prewar days. All the old craftsmen were there: the glassworker, the baker, the water carrier, the shoemaker. Each drawing was so alive, and each had a story that Hechtkopf told me about. It was riveting. Our meeting lasted five hours.

Two days later, he called me. “Listen,” he said, “I showed you the images that I drew after the war from memory. These drawings speak about all that has been forgotten — the shtetl where there was so much poverty, but such a lofty Jewish atmosphere. I left my Yiddishkeit behind, but don’t think that I have forgotten it. I want the whole world to remember what was in the shtetl. Are you willing to come and hear my stories, and then write a book about this world?”

There was nothing I’d rather do. I visited a few more times and heard so many stories. And based on that lost era, I wrote the children’s book, Mah Shekarah Ba’ayarah. The plot was fictional, but it was based on the descriptions he shared with me.

When I called to tell him that the book had been published, he was happy, but apologized, “I won’t be able to see it. I’ve gone blind, but in my mind’s eye, I see everything.”

I visited a few times to read him chapters of the book. And every time, he asked his caregiver to buy me something to eat — an apple, tangerine, or peach, something that was sure to have a hechsher.

The last time, the caregiver bought me a lemon. I ate it, segment by segment, despite its sourness, because I wanted him to smell the fruit and feel that I had appreciated his effort.

Years later, I was asked to write an article about the shtetl craftsmen of yore. Two black and white newspaper pages depicted the craftsmen from Hechtkopf’s drawings — the ones from my book. Hechtkopf didn’t know about it, though. He had already passed away.

Yet I can’t get him out of my mind, because I know that I, too, now carry the burden he bore, and which he so wanted to convey — with all their struggles, emunah, and simple, vulnerable humanity, the saga of shtetl Jews of yore.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 965)

Oops! We could not locate your form.