Take My Advice

Your ideas might be great, but do you know the best way to speak up — and when to keep quiet?

"Take my advice. I’m not using it.” Ever heard that line?

Ha, ha.

Yet we all probably know at least one person like that, the kind who loves to dispense sage wisdom and does so without inhibition. ‘Nuff said.

But give advice without thought, say Harvard Business Review writers David A. Garvin and Joshua D. Margolis, and watch the possible consequences: misunderstanding and frustration, decision gridlock, subpar solutions, frayed relationships, and thwarted personal development.

The good news: advice-giving can be a learned skill. So how do you become the sort of person people want to listen to? Here’s some wisdom, uh, advice, from professionals and laypeople who’ve weighed in on how to respond best.

WHAT THEY’RE REALLY ASKING

Take this one: “My friend hurt me badly, and she doesn’t know it. I can’t forgive her.”

Spoiler alert: this once happened to me.

“I’m so mad,” I told a mentor-friend of mine then, ranting and raving about a comment another friend had made and how I thought I could never forgive her.

“Let it go,” was her reply. “If you were the recipient of such a comment, it was obviously G-d’s will. You needed to hear it. Your friend was only the conduit.”

I ended the call fast.

Her words may have been great advice, but there was one slight hitch. I wasn’t asking for advice. I just wanted to talk.

Apparently, I’m not alone. According to Psychology Today writer and therapist Richard B. Joelson, people often appear as though they’re asking for advice, but they don’t really want it. What they’re looking for when sharing difficult life situations, says Joelson, is an attentive ear rather than a request for help.

“People often find their own solutions when they have an opportunity to express their feelings in an atmosphere of acceptance, patience, tolerance, and support,” says Joelson. “Active and attentive silence may, at times, be more helpful than anything one person can say or do to help another.”

Mishpacha columnist and community leader Rabbi Ron Yitzchak Eisenman concurs, sharing an incident in which a woman, a single mother, asked to consult with him about the difficulties she was having with one of her teenagers.

The woman came into his office and sobbed.

“I had nothing to offer her as far as advice,” says Rabbi Eisenman. “I sat there for 45 minutes, literally not saying a word, giving her the only thing I had: my silent support. When she was done, she got up and said, ‘Thank you, Rabbi, for listening.’ And that was it.”

That’s listening at its best, “advice” in its most artful form. “I work hard to make people feel as comfortable as possible, to listen without reacting, without judgment.”

So how do you know when your advice really is warranted?

If someone’s sharing is not accompanied by comments such as, “What do you think I should do?” or, “What would you do if you were me?” Joelson advises keeping quiet. “I assume this indicates that the speaker is primarily interested in my ear and less so my mouth,” he says.

“If I receive a yes,” he says, “then I believe the welcome mat is out.”

“Unsolicited advice,” according to Nadia Goodman in Entrepreneur, “sends the message that you’re jumping in because they can’t handle the problem. It leaves them feeling less confident and capable, undermining their ability to handle the situation themselves.”

If you’re unsure if your friend wants you to weigh in, or if she’s just venting — ask! Let the other person know what they want from you, whether that’s a supportive listening ear or practical tips.

Points to remember:

-Hone your listening skills. Most people just want to talk, but listening is often more effective, and more sensitive, than anything you’d say.

-Check that the person you’re talking to is actually soliciting advice, or otherwise just ask before taking the floor.

KNOW YOUR CAPACITY

“Help, my marriage is falling apart!”

When you’re a mentor or therapist, you’re often exposed to wrenching pain. “I carry a lot of people’s stories,” says mentor and kiruv educator Rebbetzin Joanne Dove. “I’m there for anyone who wants to talk through things, and I’m passionate about building people and building marriages.”

Rebbetzin Dove builds genuine connections with the people who come seeking her advice, because, she says, “I give from the inside and grow to truly love them. I hear so many people’s challenges, but I baruch Hashem have the ability to carry them with me and not drown in them.”

And that’s a critical skill for a mentor. Even after hearing of excruciating difficulty, you need to have the capacity to continue and do what needs to be done. “I can sit and hear someone’s story for three hours, then when she leaves, I go back to my kitchen and daven for her as I’m mafrish challah. I may go into Yom Tov with my table not set, but I know that I was there for her to enable her to go into Yom Tov calmly.”

It’s also vital to know your limits and consult with others when warranted. “You need to have someone to take advice from yourself,” says Rebbetzin Dove. “I consult with many rabbanim, rebbetzins, and experts. And as I’m a mentor, not a certified marriage therapist, I also am in touch with and ask advice from certified therapists. I have a large arsenal on which to draw upon in any given scenario, be it halachic or hashkafic.”

Points to remember:

-Make sure you are strong enough to carry the stories you’re told.

-Make sure you have your own mentors and rabbanim to seek advice from when the need arises.

DO YOUR BEST. THEN, HUMILITY

Consider Daniella’s story.

“I’d been keeping Shabbos for many years,” shares Daniella, a baalas teshuvah. “But somehow I felt my resolve dwindling, and my Shabbosim lacking meaning.”

Daniella turned to a close friend; what ideas did she have to help make her Shabbos more meaningful?

“My friend advised that I stop reading secular books on Shabbos.” But Daniella found that it didn’t help. “I just wasn’t there,” she says. “In my heart of hearts, I knew my friend was so wise and so right — but I couldn’t do it.”

Solutions also emerge best, says writer Nadia Goodman, quoting psychologist Reeshad Dalal, when you recognize that while you may have more experience, it’s the advice-seeker who may have greater expertise about the specific situation. So instead of imposing your opinion, says Goodman, “guide them through the process you might use to reach a conclusion. Ask the questions you might ask yourself, and give them an opportunity to talk through the options with you.”

In Daniella’s case, perhaps a better approach would have been, “What do you think you could do to make Shabbos more meaningful? What things are getting in the way for you?”

Sometimes what a person needs is the self-confidence to trust their intuition and make an informed choice. “Let them know that you’re here to help, but you trust them to make an intelligent decision,” writes Goodman. “Your confidence may be all the advice they need.”

“People are usually more likely to modify the advice, combine it with feedback from others, or reject it altogether, than run with it,” say Garvin and Margolis. “Try not to take offense. Offense creates distance, and distance limits trust and intimacy that lies at the heart of effective advising.”

“Be humble,” suggests Daniella, who is often in the position of advice-giving herself. “It feels good to be asked. But trust that the other person knows best, and respect where they’re at. And remember that you’re just a shaliach.”

Points to remember:

-You may have some great advice. Your advice might even be perfectly on the mark. But be humble. Be prepared to be challenged. Trust that the person is the one who really knows best. You’re just a shaliach.

BE CURIOUS

“Should I have my wisdom tooth pulled? My dentist is really pushing me to do it.”

This is a standard kind of question. So can’t you just give her the standard answer? “Listening to a medical professional is always recommended. Of course you should.”

Not so fast.

If a standard answer exists, yet your friend is still asking the question, here’s what you might want to consider: What’s going on for her that she’s chosen to share this dilemma with you? What’s really behind her question? Is she about to marry off a child and not sure if she should take the time for this now? Is it an expense that she cannot afford? Ask questions. Be curious.

Listen, listen, listen.

Having an objective point of view and the ability to see the bigger picture means that you can ask the right questions, and get a good understanding of the problem. If at that point you have good advice, and you’ve checked that your input is solicited, by all means share it.

With a caveat: Be careful not to go with the “if I were in your shoes” approach, warn Garvin and Margolis. This can be off-putting and ineffective. You can never fully step into another’s shoes, and it’s important to be aware of that.

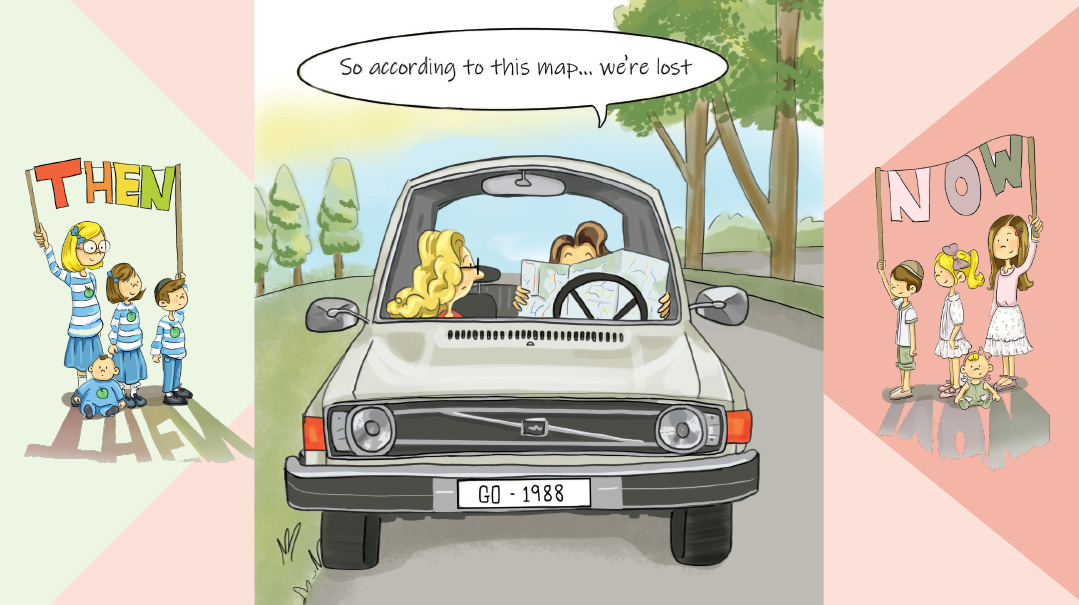

Think of yourself as being a driving instructor, they say. “While you provide oversight and guidance, your ultimate goal is to empower the speaker to act independently.”

Points to remember:

-Be curious before you jump in. Listen to what’s behind the question.

-The power isn’t yours; it’s the speaker’s. Give them that power.

BE HONEST

“Do you think we should pull my son out of his yeshivah and send him to one that has less academic pressure? I’m worried that he’s struggling and how that will affect him, but we’re so happy with his peer group and friends in his current yeshivah.”

Don’t be afraid if you don’t have the expertise to guide her and to say, “I don’t know.” It’s flattering to be asked for advice, but does that mean you need to be the one giving it?

“Wrong advice can be damaging,” cautions Daniella. “You really have to have the other person’s best interests at heart. If a person annoys you, for example, you’re not the right person to give them advice. There’s even an al cheit, ya’atznu ra, that references this. It’s a huge responsibility. Better be safe than mess it up. And always say a tefillah first.”

In the words of Garvin and Margolis: “Ask yourself whether you’re indeed a good fit. Do you have the right background? Can you dedicate enough time and effort to attend to the seeker’s concerns?” If the answer is no, you know what you need to do.

And even when you do give advice, it’s important to approach it with humility. Rabbi Eisenman likes to constantly remind people, “You’re the one who’s going to have to live with this decision,” by way of emphasizing that what he says is only an opinion and not an instruction. “From the Torah’s perspective, having less power is always better than more. I say I don’t know all the time. Because I really don’t. How can I be the one to determine what another should do?”

Points to remember:

-Consider your qualifications. Be honest if you’re not the right person.

Seeking Advice? Read This

When I’m seeking advice, there are two qualities I look for: someone whose expertise I trust, and someone who I know has my interests at heart, who takes me into consideration.

—Daniella

I need to know that the person I’m asking advice from respects my concerns, will make an effort to understand them, and has a love for people.

—Rebbetzin Joanne Dove

Humility is just as important when you’re seeking advice as it is when you’re giving it. Be willing to consider another perspective or even to be told you’re wrong. Too often, people “seek advice” because they want to hear they’re right. Nothing comes out of that, other than an ego boost.

—Daniella

Be a listener. That’s not only a trait for those giving advice. Be open.

—Rabbi Eisenman

You may not hear what you want to hear, but remember that what you hear is what Hashem needed you to hear.

—Daniella

Don’t be afraid to disagree with the advice you’re given. People aren’t infallible. You’re the one who has to own your decision in the end.

—Rabbi Eisenman

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 741)

Oops! We could not locate your form.