Sweetness and Light

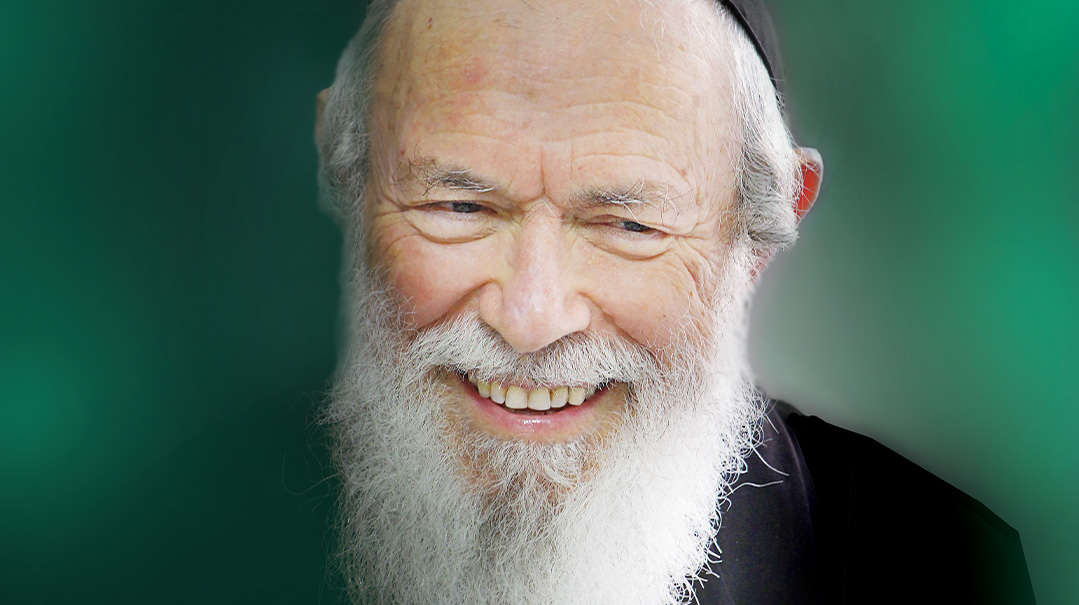

Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein is driven by a mission to show that there’s no sweetness like Torah when it’s practical and clear

Photos: Mattis Goldberg, Anachnu V'tzetzaeinu, Ariel Ochana

The dog walkers and joggers taking the air in Tel Aviv’s Hatikvah park on that mid-Elul Motzaei Shabbos in 2019 had likely never seen a stranger sight.

Instead of the soccer game that would normally have taken up the grassy expanse, the scene was something from a different world.

In the middle of this secular neighborhood — home to African migrants, Chinese workers, and poor Israelis — a chareidi election rally was in progress, graced by none other than Rav Chaim Kanievsky.

It was a bizarre sight. Hundreds of traditional locals watched in bemusement as shtreimel-clad chassidim belted out Sephardic classics like “Adon Haselichot.” They listened patiently to classic chareidi stump speeches and sundry exhortations to vote for a party who pretty much no one in their neighborhood identified with.

But with all the goodwill in the world from the audience, the strange admixture of Bnei Brak and Tel Aviv just wasn’t working. The evening threatened to be a failure, until the last speaker took the microphone.

“Isser Harel, the famous Mossad chief, used to speak about something he witnessed as a child,” Bnei Brak posek Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein began his speech.

This was a cultural reference that seemed familiar, and so the audience sat up in their plastic seats and paid attention, as Rav Zilberstein beamed around the park and started to weave his magic.

“Harel came from the Latvian port city of Dvinsk. There’s a river that flows through the city that sometimes freezes,” the rabbi continued, “and one year, a dreadful thing happened: The ice upstream melted, but that within the city didn’t. The result was a blockage that prevented the water from flowing, and threatened to drown the city.

“The authorities tried everything to remove the obstruction, including dynamite, but nothing worked. As thousands of townspeople watched the waters rise, the gentile mayor suddenly had an idea.

“ ‘Call the rabbi!’ he said. ‘He’s a holy man, and maybe, just maybe, his prayers can work a miracle.’

“Rav Meir Simcha HaKohein, the Ohr Sameiach, came out wrapped in his tallis and tefillin, and a hush fell over the massive gathering.

“The townspeople — most of them non-Jews — watched in silence as the rabbi began to pray. A few seconds went by, and the tension mounted as thousands of eyes flitted between the holy man and the frozen river, waiting to see whether the town would be saved.

“Then the incredible happened: There was a gigantic cracking, tearing sound, and with agonizing slowness, the ice sheet that had resisted even explosives began to break up. With a trickle and then a rush, the river began to flow normally, and the city was saved.

“And that,” said the speaker, bringing his Tel Aviv audience back from prewar Latvia to the topic at hand, “is the power of a Torah great. When you have my brother-in-law Rav Chaim Kanievsky sitting here, and the opportunity to vote for a party that stands for the Torah and Shabbat, it’s something that is above nature.”

The performance that night in the Tel Aviv park was a vivid display of the unique mix of qualities that make Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein a once-in-a-generation figure.

He’s a world-famous posek who spends 18 hours a day dealing with thorny halachic problems, and a confidant of some of the greatest gedolim of recent times, yet he retains that common touch and the uncanny ability to find the right words to connect with Jews of any persuasion.

In a world of labels, Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein genuinely defies classification. He’s equally at home in the litvish and chassidish worlds; greeted with open arms in a kollel in Bnei Brak or a shiur in a Shomron settlement. He’s someone who retains his own uncompromising worldview, yet seems to belong to all parts of the Jewish People.

Like the maggidim of old, stories and Rav Zilberstein are indivisible. They burst forth in a tidal wave of anecdote, mashal, and personal recollection from a childhood among the greats of Yerushalayim — or of a Mossad chief, if that’s what the audience needs to hear.

Yet amid all the storytelling, one saga — Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein’s own epic life story — remains largely untold.

It’s the story of a young boy, who despite his humble background, decided to dedicate himself to learning Torah. From prewar Poland to Yerushalayim’s Old Yishuv, the Chazon Ish and the Belzer Rebbe, Slabodka’s Rav Mordechai Shulman to Rav Shmuel Wosner, he was shaped by a wide range of influences.

And somewhere along his journey, he realized that his life’s work wasn’t to be a rosh yeshivah or chief rabbi, but to deliver a new approach to teaching.

“Torah has to be absorbed not just intellectually, but in a deep, emotional way,” he says, “and to do that, it needs to be clear and sweet, taught through real-life scenarios and stories. My task in life is to help Jews to love Torah.”

The seven decades-long chavrusa between brothers-in-law Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein and Rav Chaim Kanievsky began with Rav Chaim’s peek at the prospective chassan in Yeshivas Slabodka

When Dovid Yosef and Rochel Zilberstein made the decision to leave Mandate-era Palestine and move to America in 1943, they did so with heavy hearts.

The Zilbersteins, who hailed from Bendin in southern Poland, had arrived in Eretz Yisrael with their oldest son, Yitzchok, born in 1934, a few years before.

The rav of Bendin, Rav Chanoch Tzvi HaKohein Levin, was a son-in-law of the Sfas Emes and one of the leaders of prewar Polish Jewry. His son, Reb Itche Meir, headed the World Agudah, and later became an Israeli government minister. Although not chassidim, the Zilberstein family was connected to their hometown’s rav.

The move to Palestine proved to be the first of many journeys for the young family. They first headed for Bnei Brak, then a straggling settlement surrounded by Arab villages on the outskirts of Tel Aviv.

Those were hard times in the penniless Yishuv, as the Jewish presence in the country was known. Dovid Yosef Zilberstein found work picking fruit in an orchard near the town.

The family lived close to the Chazon Ish on Rechov Harishonim, and Yitzchok — a very bright child — began to ask him questions, displaying a precocious self-assurance.

One such question was so good that the world-famous posek wanted to write it down, and asked the child himself for a pen.

“I have a pen that doesn’t write,” the Zilberstein boy offered.

“I have a broom that doesn’t sweep,” quipped the Chazon Ish in response.

Further down the road, when he’d graduated to learning Gemara, Yitzchok went to be tested on Bava Kamma.

“If I ask you to bring a knife from the kitchen, which way should the blade be pointing?” the Chazon Ish asked him, challenging the boy with a probing question.

“The blade should be pointing toward the one holding it,” he answered. “Because Tosafos says that a person needs to be more careful to avoid damaging someone else than he is to avoid damaging himself.”

The close bond that developed between the two led to an unusual incident years later, when Yitzchok Zilberstein was learning in Yeshivas Slabodka in Bnei Brak. On one occasion, he fell sick, and the elderly Chazon Ish — in a notable display of his esteem for the bochur — came to visit him.

But the family’s time in Bnei Brak proved brief, and after less than a year in the town, they left in search of better financial opportunities and moved north to Teveria.

In what would become a pattern, Yitzchok’s mother — a daughter of Reb Avraham Chaim Bolimovski, who founded an orphanage in Lodz, Poland — encouraged him to spend time with the town’s gedolim.

Thus, he became a regular in the house of Teveria’s chief rabbi, Rav Refoel Kook. Another great figure with whom she encouraged an acquaintance was the dayan of Slonim and later leader of the Slonimer chassidus, Rav Mordechai Chaim Kastelanitz, known as Rav Mottel Slonimer.

Knowing that Rav Mottel had back pain, Yitzchok’s mother bought a special pillow and gave it to her son, telling him to arrange the pillow on the rav’s chair whenever he sat down. The strategy paid off, leading to a regular chavrusa in Rambam between the aged dayan and the young boy: Yitzchok would read, and Rav Mottel corrected him from memory.

But dedication to chinuch didn’t help pay the bills, and after a year in the country’s north, the family’s financial situation led them to Jerusalem.

And it’s there that the story of Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein really begins. Because a few months after moving to the capital’s Beis Yisrael neighborhood and enrolling Yitzchok in the Eitz Chaim cheder, the Zilbersteins found themselves facing financial pressure and a medical crisis (see sidebar), and decided to move once again — across the world to America.

But this time, the unbelievable happened: Their nine-year-old son said he wouldn’t join them, because he wanted to learn Torah.

It was an early harbinger of the utter conviction and dedication to learning that propelled his rise to greatness, the hinge on which Rav Zilberstein’s story turns.

And so, like something out of a fable, young Yitzchok remained behind with his grandfather, while his family set sail for the Goldeneh Medineh.

Rav Zilberstein’s sweet encounter with Mishpacha’s Gedalia Guttentag at his kehillah’s Beit Shemesh matzah bakery, where chocolate bars are the reward for good work

IN the fevered atmosphere of 1940s Yerushalayim, the anti-British armed groups such as Menachem Begin’s Irgun were magnets for religious youth in the city, including those in the Eitz Chaim cheder.

The head of that landmark Yerushalmi institution at the time was Rav Aryeh Levin, the “rabbi of the prisoners,” known for the care he extended to the members of the Jewish underground — the machteret — who’d been imprisoned for fighting the British.

Rav Aryeh kept a sharp eye out for the young boy who’d stayed behind without his parents. Years later, that connection would morph into family ties, when Reb Yitzchok married the Yerushalmi tzaddik’s granddaughter, Shoshana Elyashiv.

But what Rav Aryeh soon noticed was that, against all the odds, the lone boy wasn’t tempted to join the action around him.

“Most of the boys were drawn either toward money-making schemes or to getting involved in the underground movements,” says Rav Eliezer Roth, Rav Zilberstein’s son-in-law.

“There were all the reasons in the world for him to lose focus. He was so poor that one day the menahel carried him to school after seeing his bloody footprints in the snow, because he had no shoes. Yet Rav Zilberstein just wanted to learn.”

It was a tremendous internal struggle, Rav Zilberstein remembers.

“After cheder, I used to sit and learn in the Yeshuos Yaakov shul, above the Meah Shearim shtiblach. On the roof, the other children in my class were singing the anthem of the Irgun. The effort to ignore what was going on and concentrate on learning burned me inside, but I managed.”

Because Rav Aryeh Levin knew that Yitzchok Zilberstein was the only boy who could be relied on not to get swept away by the glamour of the clandestine struggle, he involved him in various efforts to help the prisoners in British jails.

One such mission involved Eliyahu Meridor, then the Irgun commander in Jerusalem, later an Israeli government minister and patriarch of a political dynasty.

Rav Aryeh Levin planned to guide the fugitive paramilitary boss across Jerusalem to a safe house, but he needed a lookout whom the British didn’t know to warn them of the approach of any police.

The ideal solution was to use a young boy, and Rav Aryeh’s choice was Yitzchok Zilberstein, because he had no previous involvement with illegal activity that could tip off the authorities to his identity.

“Walk straight ahead, don’t look left or right, and we’ll follow you,” the Yerushalmi rav instructed his pupil, “and only turn if you see the British.”

Thanks to the cheder boy, Meridor managed to evade the authorities that time, but was eventually captured and deported to Kenya.

Rav Zilberstein’s involvement in cloak-and-dagger missions eventually came to light in a discussion with his brother-in-law Rav Chaim Kanievsky. On one occasion, Rav Chaim told the story of his own involvement in the 1948 fighting.

With the tiny Jewish Yishuv ringed by Arab armies in the War of Independence, yeshivah bochurim were instructed to help with civil defense duties, including filling sandbags.

“I wasn’t very good at it,” recalled Rav Chaim, “and so after a short time, the head of the shift said to me, ‘It’s better that you go back to learning.’ ”

At that point, Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein responded with his trademark smile.

“You think you’re the only one who helped in the battle? I was the one who helped Meridor evade the British!”

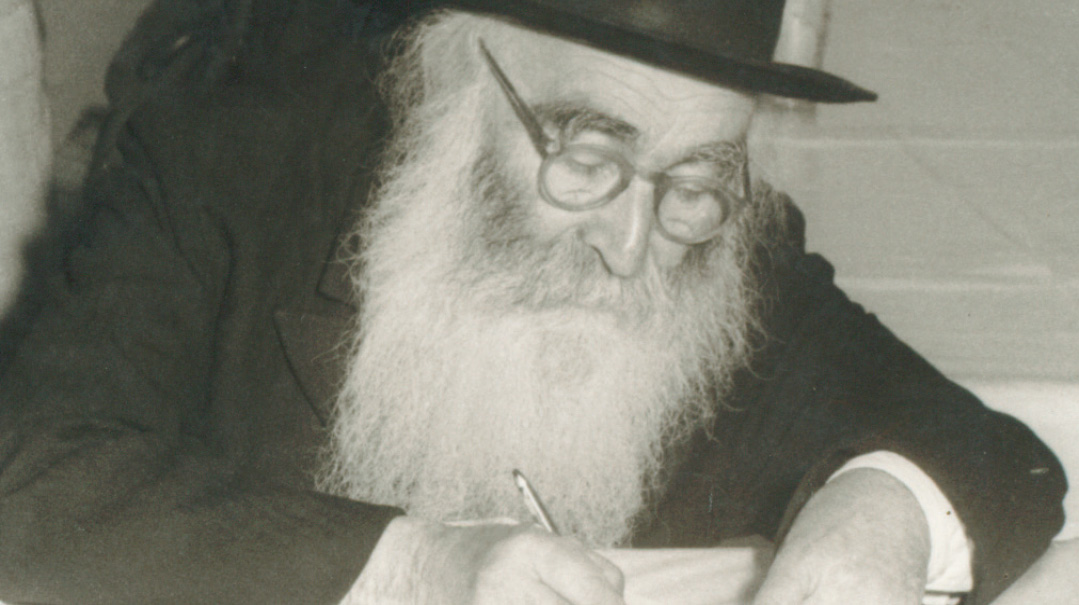

Childhood mentor Rav Aryeh Levin made an indelible impression on a young Yitzchok Zilberstein, left alone to learn Torah in the Holy Land after his parents set off for America

ON another one of those rescue missions, Rav Aryeh taught his young protégé the ultimate lesson in love for his fellow Jew — one that became the inspiration for Rav Zilberstein’s own outreach efforts.

“Once I went with Rav Aryeh to negotiate with the British the release of a member of the Neturei Karta,” recalls Rav Zilberstein.

“It took us a lot of time and effort to get to the prison, and once we got there, it took hours more to secure his release.

“But when he walked free, the man covered his eyes and refused to look at Rav Aryeh, saying, ‘It’s forbidden to look at a rasha!’ ” (a reference to Rav Aryeh Levin’s close relationship with Rav Kook ztz”l).

“At that time,” recalls Rav Zilberstein, “it really hurt me, and I exclaimed to Rav Aryeh: ‘Does the obligation to love a fellow Jew extend so far?!’

“Incredibly, Rav Aryeh’s response was one of surprise, as he turned to me, looked me in in the eye, and simply said: ‘But he’s Jewish!’

“Rav Aryeh Levin’s gaze as he said that accompanies me all the time,” concludes Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein. “We simply have no idea of the greatness of a Jew.”

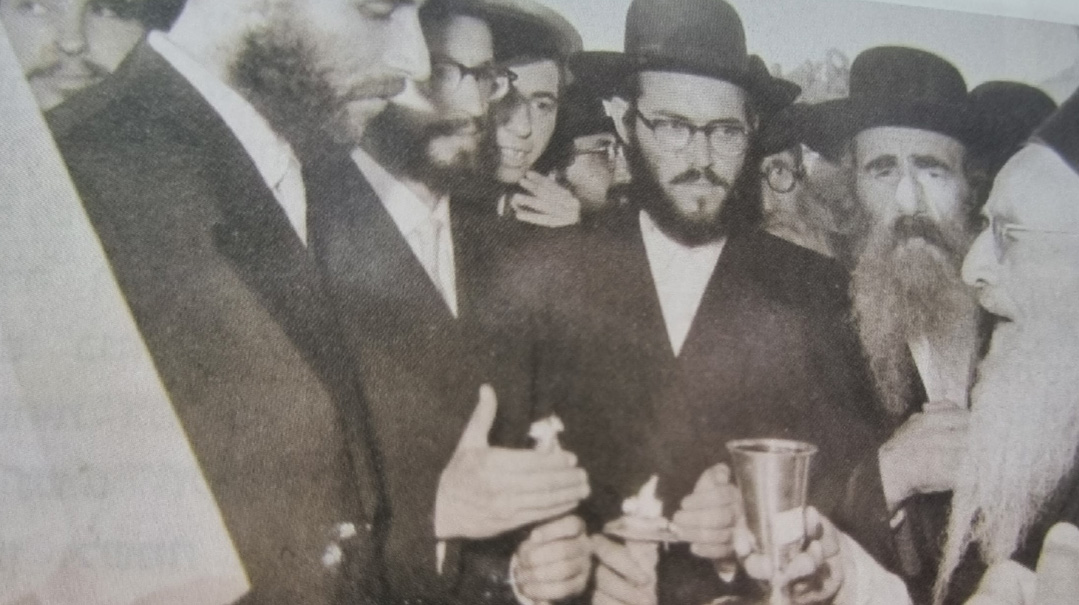

At the chuppah of his brother-in-law Rav Ezriel Auerbach. (R to L) The mekubal Rav Ovadiah Hedaya, the Steipler, and Rav Zilberstein. The Steipler, mesader kiddushin, was a mechutan of the kallah’s father Rav Elyashiv, as well as Rav Zilberstein’s own mentor

Despite the twin challenges of poverty and revolutionary fervor in those years, Yerushalayim provided an amazing array of opportunities for a young boy who loved to learn. Across the hallway from his grandfather’s Beis Yisrael apartment lived Rav Shimshon Aharon Polonsky, a great posek known as the Tepliker Rav. Another neighbor was Rav Shlom’ke of Zvehil.

Not far away lived Rav Yaakov Chaim Sofer, the Sephardi posek known as the Kaf HaChaim; once again the young boy looked for an opportunity to strike up an acquaintance by carrying the rav’s shopping bag for him on Erev Shabbos.

When someone asked a good question in cheder, a favorite pastime of the boys was to knock on the doors of the city’s gedolim to pose the question to each of them in turn.

With the best mind among his peers — plus a lack of inhibition — Yitzchok naturally stood out. The aged Yerushalmi gaon Rav Gershon Lapidos was heard to predict that the boy would be one of the gedolei hador.

That reputation led Rav Zilberstein to be among a handful of outstanding students who were sent to found a new yeshivah. Rav Sholom Noach Berezovsky, known as the Nesivos Sholom, and eventually the Slonimer Rebbe, founded his yeshivah in Yerushalayim in the early 1940s.

He asked Rav Aryeh Levin for a few of his prize talmidim to start the yeshivah with, and he acceded to the request. That initial cohort included future later luminaries such as Breslov mashpia Rav Yaakov Meir Shechter, Bobover Rebbe Rav Naftoli Halberstam, and the famous posek Rav Moshe Halberstam.

The latter’s mother wanted her son to spend time with the boy who had sacrificed so much for learning.

In a city so poor that many ate chubeza, a wild plant, instead of normal food, the Halberstams — who received money from family overseas — could afford the luxury of homemade candy made from sugar and cocoa sucked through a straw. She invited Yitzchok to join them, offering the ultimate lure.

The deprivation the young boy suffered must have been significant enough to make him look wan. In fact, Rav Aharon, the saintly Belzer Rav, called Yitzchok “der veisser — the white one,” because of his paleness.

While the Belzer Rav was known not to shake hands except through a covering, to maintain his high standards of taharah, he made a rare exception for the boy from Yerushalayim — a fact that caused some comment at the time.

Effectively growing up alone took superhuman endurance — an experience that left its mark. It was only years later, after Rav Yitzchok was already married, that his parents could afford to visit Israel. And it took even longer than that until he would get to know his far younger American siblings, sister Mrs. Rut Cywiak and brother Reb Shlomo Silberstein.

Even today, says Yonatan Shlush, who is married to Rav Zilberstein’s granddaughter, the Rav recalls the insults that the other children threw at the outsider from Poland, and expresses amazement that of all them — he, the newcomer — had made it so far.

“Not long ago, the Rav was invited to address a large public gathering, and I showed him the sign with the honorific ‘Maran Posek Hador,’ ” says Shlush.

“At first, Rav Zilberstein laughed away the titles, but then said: ‘Would anyone believe that no one knows the names of those children, yet I — whom they wouldn’t even call by name — am known as Maran Posek Hador?!’ ”

IN 1948, the 14-year-old bochur entered Yeshivas Slabodka in Bnei Brak, where he would spend the next decade and a half. It opened before Rav Zilberstein the worlds of mussar, lomdus, and eventually, semichah.

“From Rav Eizik Sher, the rosh yeshivah, I learned what love of Torah is,” says Rav Zilberstein.

“Once, Chief Rabbi Isaac Herzog visited the yeshivah, amid great fanfare. In addition to being a tremendous gaon, Rav Herzog was surrounded by the trappings of his office, which carried a lot of prestige. In those days, the chief rabbi would be accompanied by police outriders, and he would travel in a limousine whose license plate was simply the number 2, indicating that it came second in importance only to the prime minister’s.

“But when the Chief Rabbi came into the yeshivah, Rav Eizik Sher simply said to him: ‘Eizik, Eizik — when will you leave all of this behind and just sit and learn like the bochurim?’ ”

That utterly genuine rejection of outward prestige left a powerful imprint on the bochur. “For that alone,” says Rav Zilberstein, “Rav Eizik Sher became my rebbi in hashkafah.”

Rav Sher’s son-in-law Rav Mordechai Shulman also became a key figure in Rav Zilberstein’s life. Alongside his brilliance and hasmadah, the rosh yeshivah taught a lesson in education.

“Bochurim used to want to go to the beach, but Rav Shulman didn’t ban it — instead, he bought a seven-seater car, and once a week on Friday the best bochurim would go to the sea with him.

“I learned from this that the way to educate is not only to say what is forbidden, but to give the young person the feeling that he can enjoy a life of kedushah.”

Clearly, though, Rav Zilberstein himself wasn’t struggling with the urge to play truant. Years later, his friend and later rosh yeshivah of Ofakim, Rav Chaim Kamil, reminisced about their joint dedication to learning.

“One Shabbos, it was too hot to sit inside the yeshivah and learn,” he remembered, “and so we walked around the neighborhood repeating to each other the Tosafos in Maseches Gittin. I said one, then Rav Zilberstein said one, until we’d finished the whole masechta.”

But his eventual attainments in Torah study were the product of grueling work, not some unusual talents.

“I once expressed amazement to my grandfather when he quoted a little-known Tosafos verbatim,” says Gedaliah Kook, a son of Teveria mekubal Rav Dov Kook and Rav Zilberstein’s grandson. “He replied, ‘If you had learned it hundreds of times before the age of 30, you would also know it well.’ ”

Despite his constant involvement with Torah learning, it was only some years later that Rav Zilberstein felt that he’d crossed the final bridge into a life of dedication to Torah.

“Before my parents moved to America, they left me a curtain store in Teveria to serve as a source of income for me,” he says.

“From time to time I had to travel and supervise the store and the employees, so I would take with me a sefer, Shev Shemaitsa from the Slabodka yeshivah and learn the whole way up north — back then a journey of half a day.”

The demanding subject matter — the sefer is very challenging even in normal circumstances — was testament to Rav Zilberstein’s ability to lose himself in his learning, whatever the circumstance.

But despite the fact that he was able to memorize sections of the sefer en route, he was unsure whether the time invested in the round trip was justified, and decided to ask Ponevezh mashgiach Rav Yechezkel Levenstein.

“You’re not doing anything wrong, but you won’t become a gadol like that,” was Rav Chatzkel’s uncompromising answer.

In another display of single-minded dedication to Torah growth, Rav Zilberstein acted immediately: “Without telling my parents, I sold the store for a loss and returned to the yeshivah.

“In order to achieve kedushah,” he summarizes what he took from the episode, “you need to be willing to sacrifice, and Hashem rejoices in the dedication of each Jew.”

Rav Zilberstein testing a group of boys at his kollel in Holon. Due to health precautions, he speaks to the colorful crowd via microphone from the ezras nashim

Rav Zilberstein eventually became a preeminent posek, but that might not have happened without the insistence of a chassidish rav.

It was shortly after his marriage to Shoshana Elyashiv that Reb Yitzchok, the newly minted yungerman, went to ask a sh’eilah from a local posek.

Rav Ungar, the rav in question, was shocked that the budding talmid chacham was unaware of the answer. “It’s a clear Pri Megadim,” he exclaimed, referring to one of the commentaries on the Shulchan Aruch. “How can an avreich not know that?”

Zilberstein was determined to do something about it immediately, by throwing himself into gaining proficiency in halachah.

“He went into Slabodka, rapped on the bimah, and declared to the shocked yeshivah, ‘Rabbosai! We’re not learning Yevamos anymore — it’s time to learn Chullin!’ ” says Rav Roth.

The declaration — which took place while the rosh yeshivah, Rav Mordechai Shulman, was overseas — set off a mighty debate among the bochurim. It concluded with a vote that came out narrowly in favor of the revolutionary move to abandon the yeshivah masechta and learn halachah, and a consensus decision that ultimately the Rosh Yeshivah would need to be consulted.

Later that day — with Maseches Chullin now underway in Slabodka for the first time — the answer came back from Rav Shulman: “If you haven’t started, don’t start. If you have, don’t stop.”

The incident, another demonstration of Rav Zilberstein’s leadership and singlemindedness, signaled an abrupt change of course for the young avreich.

A short while later, he went to Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel to share a shtikel Torah, as he’d often done in the past, as the Mirrer rosh yeshivah was known to reward chiddushim with money.

But this time, Rav Finkel wasn’t happy. “Why have you given up Yevamos to learn Chullin?” he wanted to know.

When the visitor had filled him in on his change of course, the Rosh Yeshivah responded firmly.

“The Pri Megadim will go in one ear and out of the other,” he said. “If you really want to know psak, there’s a young rav in Bnei Brak who will one day be a gadol b’Yisrael. His name is Rav Shmuel Wosner, and you should go to learn Gemara and poskim with him.”

Thus began Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein’s entry into the world of halachah. Under the guidance of Rav Wosner — who up until then had been an obscure neighborhood rav and founder of Chachmei Lublin, a chassidish yeshivah in Bnei Brak — the avreich applied his phenomenal abilities to mastering psak.

For years, Rav Wosner himself had no idea what had brought Rav Zilberstein to his door.

But just before his petirah at age 101 in 2015, the Vienna-born posek asked for Rav Zilberstein to visit. It was the middle of the night, and yet Rav Wosner was agitated and was calmed only by the arrival of his protégé.

“Why did you come to me that day?” he wanted to know. When the full story came out, Rav Wosner looked at his visitor with pride and said, “You were my first talmid.”

When Rav Elyashiv heard that Yitzchok Zilberstein sang a joyful melody while learning, he knew it was a perfect chassan for his family. Later, under his father-in-law’s tutelage, Rav Zilberstein went on to become a leading expert in medical halachah

It’s Thursday night, and in the spacious beis medrash inside Bnei Brak’s Maayanei Hayeshuah hospital, there’s a buzz in the air. A crowd of doctors, rabbanim, and random visitors wait for a shiur that is the end product of that prodigious drive for learning all those decades ago.

Even in a country where hospitals have shuls as a matter of course, Maayanei Hayeshua is in a different league. Thanks to the hospital’s founder, Dr. Moshe Rothschild, formerly of Zurich, the shul is an authentic enclave of Yekkish nusach in the heart of Bnei Brak — down to the paroches dedicated in memory of the Yekkishe Schwab family.

As the bookcases attest, the learning that goes on here isn’t of the variety — the beis medrash is home to a number of high-level kollelim, including one led by Rav Zilberstein’s son-in-law, Rav Eliezer Roth.

This hospital also played host to the encounter between halachah and modern medicine that has come to define Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein’s contribution to the halachic world.

The blend of real-life scenarios and anecdotes that Rav Zilberstein employs to teach Torah comes to life in his weekly shiurim to the doctors now gathered in the room.

“If a wife wants to cook healthily for her husband,” he begins, gazing round the room with his smile, “but he complains that the food is bland and needs more salt and sugar — does the wife have to listen?”

It’s a purposely provocative scenario, one of countless such that stem either from a genuine question, or an attempt to throw the underlying halachic principles into sharp relief.

The scenario achieves its intended purpose: provoke a round of laughter, and an animated debate among the audience about the halachic status of healthy eating.

Rav Zilberstein adds to the merriment by a droll imitation of the husband pleading to eat unhealthy food.

“I have to have something with sugar, because it’s pikuach nefesh — I could die from eating what you give me!”

But he pivots immediately to the bottom line, a radical application of the question at hand to a real-life case of triage in a hospital ER.

“I want to say a chiddush. If two people come into the hospital, with exactly the same condition and the same prognosis, and there’s a question of who to treat first, the answer is clear: the one who looks after his health has priority.”

It takes a few minutes to explain the halachic reasoning, in a process peppered with Yerushalmi Yiddish, puns, and anecdotes of his youth.

But the crowd — an eclectic mix of rabbinic and medical, chareidi and dati-leumi — is caught up in the sound-and-light show that is Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein as he teaches Torah.

At the opening ceremony for the Maayanei Hayeshua’s mental health hospital, a first-of-its-kind religious institute. Rav Shmuel Wosner (sitting, third right) initiated Rav Zilberstein into the world of halachah. Between them is hospital founder and Rav Zilberstein’s long-time confidant, Dr. Moshe Rothschild

The monthly “Doctors’ Shiur,” as the event became known, originated in 1974 with one religious medical professional, Dr. Dov Erlich, then a military doctor responsible for the Gaza coast region.

He approached Rav Zilberstein with some questions, and brought along colleagues to do the same, and then suggested that Rav Zilberstein deliver a shiur on medical dilemmas.

“Rav Zilberstein told Rav Elyashiv about the idea, but admitted that he didn’t feel qualified to take on the complex questions,” says Rav Roth. “But his shver told him not to worry: ‘Come with the list of topics that you want to cover, and I’ll make time each month to go over them with you.’ ”

Thus was born a shiur, and a decades-long chavrusa between Rav Elyashiv and his son-in-law. At its peak, the shiur would draw up to 300 doctors, both religious and not.

The monthly sessions led to Rav Zilberstein’s emergence as a world authority on medical halachah, and were codified in the 40-volume Chashukei Chemed, which deals extensively with complex medical problems.

One of the medical professionals who got to know Rav Zilberstein through the shiurim is Professor Sudi Namir, once a well-known physician in Gaza’s Gush Katif region and now a senior doctor in the Maayanei Hayeshuah hospital.

“As a medical student in Ben-Gurion University in the Negev, I heard Rav Zilberstein for the first time when he was brought in to give a talk to the doctors. We all saw that he was extremely knowledgeable about medicine, and he would listen carefully to all sides of the questions posed. As I got to know him, I saw that he is a genius across all fields of Torah, which enables him to rule in these complex areas.”

As a doctor in Gush Katif, Namir was faced with terrorism-related questions involving triage and mental health that required broad shoulders to resolve. The address, naturally, was the rav from Bnei Brak.

“What’s unique about Rav Zilberstein is that he was blessed with the gift of speech and an ability to infuse technical halachos with a certain appeal and sweetness,” Namir explains. “That’s why you’ll find major scholars and ordinary people sitting there enjoying the same shiur.”

When Teveria mekubal Rav Dov Kook (left) married the Zilbersteins’ oldest daughter, Rebbetzin Leah, it was the closing of a circle: Rav Dov’s grandmother had pushed Rav Yitzchok’s own shidduch. Joining the conversation is Rav Zilberstein’s son-in-law Rav Eliezer Roth

Over time, Rav Zilberstein’s involvement with the medical-halachic interface led to a surprise suggestion from Rav Shach.

The Ponevezh Rosh Yeshivah wanted Rav Zilberstein to create a school to train chareidi doctors. Rav Shach even secured a grant of land for the proposed institute. A revolutionary idea for a city dedicated to the singleminded pursuit of Torah study, the idea fell by the wayside not for ideological reasons, but because of a real estate dispute that broke out over the plot of land.

Rav Shach’s faith in Rav Zilberstein’s abilities extended to that of his wife, Rebbetzin Shoshana.

When Menachem Begin’s Likud took power in 1977, after decades of Labor Party rule, Begin told then-Agudah MK Shlomo Lorincz that he was free to rewrite the laws on religion and state.

Rav Shach called Rav Zilberstein and asked him to deal with the law on abortion. The Rosh Yeshivah told him to go to the Knesset committee responsible for the issue and testify in front of them.

“But only go with your wife,” he said. “As a woman, she can share a mother’s perspective that will get a hearing where you can’t.”

Subsequently, the media wanted to interview her, and Rav Shach said: “Of course she should! If she’s sure of her truth, she’ll do well.”

The story of Rav Zilberstein’s rhetorical powers is a tale in itself.

The Zilbersteins were still newly married when the rosh yeshivah of Lucerne, Switzerland, Rav Yitzchok Dov Koppelman, asked Rav Mordechai Shulman to suggest a candidate for a maggid shiur. One name came back: Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein.

Before he left for Switzerland to make his first forays into the world of teaching, he took advice from his own teachers about the most effective methods.

One address was Rav Yechezkel Abramsky, who had left his position as av beis din in London to live in Israel and gave shiurim in Slabodka, where he gave Rav Zilberstein semichah.

“When I went into Rav Abramsky for his brachah before I left, he asked me to sit down so he could share his guidance about how to teach talmidim,” recalls Rav Zilberstein.

“He opened a Tehillim to the words of Hallel, Hayam ra’ah vayanos…mah lecha hayam…?’

“Dovid HaMelech has already said that the sea fled,” said Rav Abramsky, “so why does he repeat it as a question?”

“Know,” explained the former talmid of Rav Chaim Brisker, “that the only way to convey the Torah to the students is for it to be interesting. That’s why Dovid said it in the form of a question and answer — a format which provokes interest.”

“That idea has accompanied me ever since: the way to pass on the Torah is to show its sweetness,” says Rav Zilberstein.

“My father-in-law, Maran Harav Elyashiv ztz”l, used to say that the Torah is called shirah, a song, as it says in Devarim, because it must be sweetened with song, meaning through stories, riddles and meshalim. That leads to the second half of the pasuk: ‘And teach the children of Israel — put it in their mouths.’ Through the sweetness, the Torah is absorbed.”

The Zilbersteins’ time in beautiful Switzerland proved to be idyllic, and the new experiences and setting naturally provided the master storyteller with fresh material.

Even 50 years on, it’s clear that the interlude made an impression. Over the course of two shiurim, Rav Zilberstein mentions the Alpine country twice. He laughs when he tells of an encounter with a Swiss judge who was interested in the Biblical view on capital punishment, and of an acquaintance who kept a bench in a park free by writing on it “Forbidden to Occupy” and relying on the Teutonic sense of obedience to keep it free.

But it was Rav Zilberstein’s uplifted feelings on encountering the beauty of Switzerland that led him to come home. After four years there, he hosted his rosh yeshivah Rav Mordechai Shulman, and the two went for a walk. The scene that followed was recorded by Rav Zilberstein in the sefer Shoshanas Ha’amakim that he wrote in memory of his first wife.

One day I was walking with Rav Shulman on the street and I said to him, “Isn’t the air here good? Isn’t it clear?” The Rosh Yeshivah turned to me, shaken by the words, looked into my eyes, and said to me: “I don’t like your words. Has the air of Switzerland become beautiful to you? I thought you came here for the holy atmosphere! What kind of talk is this?”

When I told my wife what had happened, she said to me: “It’s time to return to Eretz Yisrael. We’ve been here for over three years — enough is enough. The Rosh Yeshivah’s words are like a Bas Kol — a sign from Heaven to tell us to change.”

Rav Zilberstein’s own record of the incident shows what faith he placed in his wife’s judgment.

Rebbetzin Shoshana, who was Rav Elyashiv’s fourth child, was very sensitive to other people’s feelings. She used to refrain from walking with her husband in the street, lest they meet a widow who would be hurt by the sight of a couple walking together.

The Rebbetzin, who passed away in 1999 leaving behind six children, was a school teacher in Holon, a secular city near Tel Aviv. She tried to wash for Hamotzi as often as possible. “I live far away from my parents,” she explained, “and so I can’t honor them. But when I say Bircas Hamazon, I can say, “HaRachaman Hu yevarech avi mori.”

Today, Rav Zilberstein’s stories have become ubiquitous via his Aleinu L’Shabei’ach and Tuvcha Yabiu series. Both are extensive compilations of hashkafah and mussar interwoven with stories, edited by Rabbi Moshe Zoren, that became bestsellers in Hebrew and English.

But for decades, Rebbetzin Shoshana was against publishing her husband’s stories and meshalim. “I don’t want the Rav to be seen as a storyteller, when he’s a posek,” she said.

It was Rav Dov Yafeh, the mashgiach of Kfar Chassidim, who finally persuaded Rav Zilberstein that the time had come to share the stories in print form.

“The baalei mussar have vanished, and mussar has less effect today anyway,” he said. “But because you are a man of halachah, a product of Slabodka — you will be listened to, and your stories are the mussar we need today.”

The scene at a matzah bakery in Beit Shemesh a week before Pesach bears out the truth of those words. Rav Zilberstein takes his duties as rav of Bnei Brak’s Ramat Elchanan neighborhood seriously, and so he’s come to supervise the matzah production for his community.

His combination of friendliness and magnetism is obvious as he’s mobbed straight away by people wanting to say hello. On the table in front of him are spread out dozens of chocolate bars — a long-standing and unusual matzah-baking innovation.

“Anyone who rolls the matzah without speaking and with kavanah will get one of these,” he smiles to the crowd of adults.

Naturally, he speaks before the session begins, and the crowd that forms around him is a study in the kind of universal appeal that this elderly rav holds.

Next to a chassid is a middle-aged man wearing a kippah, who stands shoulder to shoulder with someone fashionably dressed in a pink shirt — and all stand with the slightly slack-jawed gaze that seems to characterize Rav Zilberstein’s audiences when the stories begin.

But it’s not just the stories — it’s an acceptance of Jews whoever they are and whatever they look like.

Where many pay lip service to the concept, Rav Zilberstein lives it.

“The rav gets along with everyone,” says Rav Eliezer Roth. “Ramat Chen, where he moved so that his second wife shouldn’t have to acclimate to unfamiliar Bnei Brak, is an affluent area where many senior army officers live. He and his wife go for a walk at night, and people — many of them secular — stop to greet him.”

Golden rays from the setting sun glance off the low-rise buildings just off the main thoroughfare of Holon, and Ethiopian teens in their soccer strip walk past stores with signs in Russian. The secular city near Tel Aviv has seen better days: once a bastion of the secular Ashkenazi elite, it’s now dilapidated and home to different immigrant communities.

But between the secular passersby, there are frequent hints of a wider religious presence. A boy with peyos barrels past on a scooter; a Bais Yaakov girl crosses at the lights.

The story of Holon’s transformation is the largely unknown story of Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein’s activism and institution building.

It all began in 1967, when Holon’s chief rabbi, Rav Dovid Wein — a talmid of Slabodka who was close to the Chazon Ish — was niftar.

Rav Wein — an uncle of the noted rosh yeshivah and historian Rabbi Berel Wein — left no children behind, and some talmidim wanted to perpetuate his legacy by funding a kollel in the city.

Rav Bezalel Zolty, the av beis din of Yerushalayim, was asked to be a patron of the institution, and undertook to select a rosh kollel. He chose Rav Zilberstein, who began to spend significant time in the city.

“My father-in-law wanted to reach out to the secular Jews around the kollel, and he began to say a shiur in halachah, and to come every Shabbos to speak in the city’s Beit Knesset HaGadol,” says Rav Roth.

“Rav Zilberstein had a vision for the kollel avreichim to be agents of change, not just passive. They had to go out and persuade parents to send their children to a religious school, and that’s how he came to open what became the Beis Dovid schools — a Talmud Torah for boys and Bais Yaakov which today has 400 pupils.”

The drive to draw secular people into the beis medrash was something that Rav Zilberstein identified as the key to the greatness of a rabbinical colleague from a very different background.

“Do you know which of the gedolim I most admire?” he asked his son-in-law Rav Roth. Given his reverence for Rav Elyashiv and Rav Chaim Kanievsky, the answer was surprising.

“It’s Rav Ovadiah Yosef,” he answered, “because as well as learning, he traveled all across the country persuading one parent after another to send their children to Torah schools.”

That same effort bore fruit in Holon. Over the decades since, 14 talmidim — products of his own schools — have become rabbis across the city. Despite his tremendous learning and teaching commitments, Rav Zilberstein continues to raises the vast budget for the schools’ operations — all without going overseas.

Over the years, he’s spent countless hours in the city. Until today, he tests the schoolboys in his cheder weekly, and spends the bulk of his waking hours in the kollel at the top of the building.

Rising at 4 a.m. in his home in Ramat Chen, an upmarket suburb of Ramat Gan where he lives with his second wife Tovah, he heads for Bnei Brak’s Ramat Elchanan, where he’s been rav since 1980, and learns and gives a shiur there before davening vasikin.

Afterward he answers sh’eilos, and then leaves for Holon at 9 a.m. Still very fit at age 89, he marches up five flights of stairs to his room above the kollel, where he fields halachic questions from all over the world.

He himself doesn’t write the teshuvos; there’s a team of talmidei chachamim who draft an initial response, which he subsequently reviews and either alters or signs off on.

The vast output is a function of his sense of order — everything in his life runs like clockwork — but also because of his voluminous note-taking.

As soon as a new topic comes up in regular conversation or with a chavrusa, he takes a pen and says, “Potchim tik — let’s open a file.”

Often enough, that phrase becomes literal, as he opens a new file under a person’s name or the subject, to join the vast quantities of other files that preserve his learning on everything from Maharal to medicine.

That part of his day concludes by 6 p.m., when he leaves to deliver a round of shiurim either in Bnei Brak, Ramat Chen, or Holon, until late at night, only to begin the cycle again a few hours later.

Walking up the stairs of the boys’ school building on Rechov Berdichevsky late on a Tuesday afternoon, the success of Rav Zilberstein’s labors in the city is obvious. With pictures of the Chazon Ish, Rav Ovadiah Yosef, and a range of gedolim on the walls, this could be any chareidi school in Bnei Brak or Yerushalayim.

Yet the pupils here are mainly the children and grandchildren of locals who became baalei teshuvah through Rav Zilberstein himself.

One such is Yonatan Shlush. He runs Kollel Beis Dovid, which operates on the fifth floor of the school building, and he married the rav’s granddaughter, at Rav Zilberstein’s suggestion.

Inside the large beis medrash that houses the kollel are avreichim, some of whom are studying with a range of locals, mostly wearing knitted kippahs.

As 6 p.m. approaches, a crowd assembles for Rav Zilberstein’s weekly shiur, which often plays host to different school classes from around the country.

This week it’s a school from Bat Yam. The teacher is a Gerrer chassid, but it’s no chassidic cheder — the range of black yarmulkes, white knitted equivalent, and plenty of sports gear show that this is a religious school for a very mixed student population, perhaps affiliated with the Shas school system.

At the glass partition of the ezras nashim above, Rav Zilberstein appears and takes a seat. As a medical precaution, he’s been very careful in recent years to be separated from crowds, and so he interacts from above via a microphone.

“Shalom, yeladim,” he calls out warmly to the boys below. He’s met by a respectful silence, and tries again.

The group’s teacher steps in and coaches the boys: “Shalom, Kevod Harav.”

“Oh, that’s better,” Rav Zilberstein smiles. “I heard that you are studying Bava Kamma. Who can tell me what are the arba’ah avot nezikin?

One boy bravely stands, fluently quoting the mishnah at the beginning of the masechta, and Rav Zilberstein warmly congratulates both him and the teacher.

“Who knows what the word ‘Mav’eh’ means?” he continues, referring to one category of damage listed by the mishnah.

The answer to the question — which is a debate in the Gemara itself — sets off a hubbub among the boys as they discuss it, and when things settle down, Rav Zilberstein once again follows his playbook.

“Did you know that guide dogs can cost tens of thousands of shekels to train?” he asks rhetorically, and launches into an anecdote about someone who made money by selling such animals. He’s got his audience — young and old — captive, before arriving at the scenario that he wants the boys to think about.

“What happens if a blind man is invited into someone’s house and then his well-trained guide dog goes and licks an expensive steak that is sitting there in the open?

“On the one hand, it’s unusual for this particular dog to ignore its training, but on the other hand, can dogs as a rule be expected to do so? Additionally, is licking a piece of meat considered damage?”

It’s a classic example of the mix of anecdote and halachic scenario that is Rav Zilberstein’s stock in trade. The earnest debate that ensues is only interrupted when he remembers that there’s something missing.

“Did they give you candies?” he asks the boys assembled below.

While they receive their treats, Rav Zilberstein leans back with his dazzling smile, and takes in the sight of the boys below, enjoying the candy and still basking in their achievements in answering the Rav’s questions.

They’re discovering a secret he’s known ever since he was little Yitzchok, a nine-year-old Yerushalmi kid on his own: There’s no sweetness like Torah when it’s practical and clear. —

The Imrei Emes of Gur delivering his famous speech about the Holocaust in the Old City’s Churvah shul in 1942. Yitzchok Zilberstein was there as a young boy, hearing a message he never forgot

“You’ll Know Shas”

While the Zilberstein family had moved all around Eretz Yisrael in search of financial stability, it was a medical crisis that persuaded them to leave for America — and led their son Yitzchok to the door of the great Gerrer Rebbe.

In 1943, the Imrei Emes, as the rebbe was known, had been in Eretz Yisrael for a year. He’d escaped the Nazi onslaught on his native Poland and arrived in Eretz Yisrael, where, from the bimah of the Old City’s Churvah shul, he exhorted the Jews of the country to do teshuvah. A picture of the event — which a nine-year-old Yitzchok attended — has survived.

So shortly after the family moved to Yerushalayim and Rochel Zilberstein’s pregnancy went disastrously wrong, her son knew where to go: He ran to the home of the Imrei Emes, and demanded to speak to the Rebbe.

The gabbai, Reb Chananiah Schiff, answered the door and told the young visitor that there was no way that he could gain entry dressed as he was.

“So give me your hat and jacket and I’ll go in!” the boy said boldly.

Draped in the ridiculously, overlarge adult garments, he went in to the Rebbe’s room, handed in the kvittel, and broke down crying.

Ignoring the gabbai’s instruction to wait until the Rebbe spoke, Yitzchok plucked up the courage and said a few short words: “My sandek was the Bendiner Rav.”

The effect, recalls Rav Zilberstein, was immediate: “The Rebbe started shaking and tears came to his eyes. Remember that this was in the middle of the Holocaust, and I was the first person he’d met from Bendin, where his brother-in-law was rav.

“The Imrei Emes was so moved that despite the fact that the Mishnah Berurah says that you’re only meant to use one hand, he placed both hands on my head, and gave my mother a brachah, and then gave me a series of brachos.”

“Some I can share — such as that I should merit to know Shas — and some I can’t, but they were all fulfilled.”

Erev Shabbos on the roof of Slabodka, Rav Zilberstein (back row, left) is wearing the new suit made from the cloth that Rav Mordechai Shulman sent from overseas (and that convinced him to stay put and not switch yeshivos). Standing two away from him (back, second right) is Rav Avraham Yitzchak Lanel, later av beis din in Rechovot and Rav Zilberstein’s chavrusa

First Bochur in Brisk

Had it not been for a new suit, Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein may well have become famous as a leading Brisker.

It all began in the 1950s, when the Brisker Rav’s son Rav Berel Soloveitchik went looking for a group of outstanding bochurim to found what became today’s Yeshivas Brisk in Yerushalayim.

By then Yitzchok Zilberstein had emerged as an outstanding name in the yeshivah world, and Rav Berel invited him to join.

He dangled a glittering incentive to entice the bochur to come on board: a weekly chavrusa with the Brisker Rav.

Rav Zilberstein agreed to transfer from Slabodka, but when he went back to Bnei Brak to take leave, he met the Rosh Yeshivah’s wife.

Rebbetzin Shulman took an active role in running the yeshivah, and she said to the bochur: “See what beautiful cloth the Rosh Yeshivah has sent for you from overseas! He wants the best bochurim to have a high-quality suit.”

“I saw what hakaras hatov I owed to the Rosh Yeshivah, who did everything for us,” says Rav Zilberstein, “and so although I was the first bochur in Brisk, I never went there.”

A Shidduch and a Song

Rav Zilberstein’s shidduch with Rav Elyashiv’s daughter Shoshana was anything but a foregone conclusion: She was the daughter of a posek of growing renown, and although he had a stellar reputation in the yeshivah world, the Zilbersteins were simple people from a chassidic, non-rabbinic background.

But then a figure from early in Rav Zilberstein’s life stepped forward.

“Rav Refoel Kook, the chief rabbi of Teveria, knew him from the family’s time in the city,” says Gedaliah Kook, a grandson of Rav Zilberstein and descendant of Rav Refoel. “His wife, Rebbetzin Rachel Kook, and he advocated for the shidduch.

“Years later, things came full circle when the oldest daughter born from that shidduch — Leah Zilberstein — married Rav Dov, the oldest grandson of Rav Refoel and Rachel Kook.”

But there was another important player behind the shidduch: Rav Chaim Kanievsky, who would share an extremely close relationship with Rav Zilberstein.

“Rav Zilberstein’s shidduch came about because of his special, melodious way of learning,” says Rabbi Eliezer Roth, who heard the details from Rav Chaim Kanievsky a few years ago.

“One Friday morning, Rav Zilberstein was learning in Lederman’s Shul on Bnei Brak’s Rechov Rashbam, when Rav Chaim Kanievsky walked in.

“He saw my father-in-law learning with total concentration, and he said to me, ‘It’s the same tune as he always had.’ ”

As Rav Elyashiv’s oldest son-in-law, Rav Chaim had been assigned the job of inquiring about all the serious shidduch suggestions that came for the Elyashiv girls.

When Rav Chaim Kamil suggested his friend Yitzchok Zilberstein for Rav Elyashiv’s daughter Aliza Shoshana, Rav Chaim made his way over to Yeshivas Slabodka in Bnei Brak in time for afternoon seder, and sat down near the bochur.

Over the course of the afternoon, he discovered that the prospective chassan hardly raised his eyes from the Gemara, and yet he made his presence felt across the beis medrash by the joyful melody with which he learned.

At the end of the seder, Rav Chaim exchanged a few words with the man who would become his brother-in-law and chavrusa for more than six decades, and then left.

“When I went to Rav Elyashiv,” Rav Chaim told Rabbi Roth, “I told him only one thing: ‘He learns with a beautiful tune.’

“Rav Elyashiv asked me to repeat it, and when he heard my imitation, he said, ‘This bochur is for us, because of his joy in learning.’ ”

Given Rav Elyashiv’s own lifelong practice of learning aloud to a soft niggun, the “song test” made sense.

But it was only decades later, when Rabbi Roth told his father-in-law Rav Chaim’s end of the story that Rav Zilberstein connected the dots.

“I always wondered how Rav Elyashiv chose me without a bechinah , but now I know that it was the joyful niggun that was the test.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 956)

Oops! We could not locate your form.