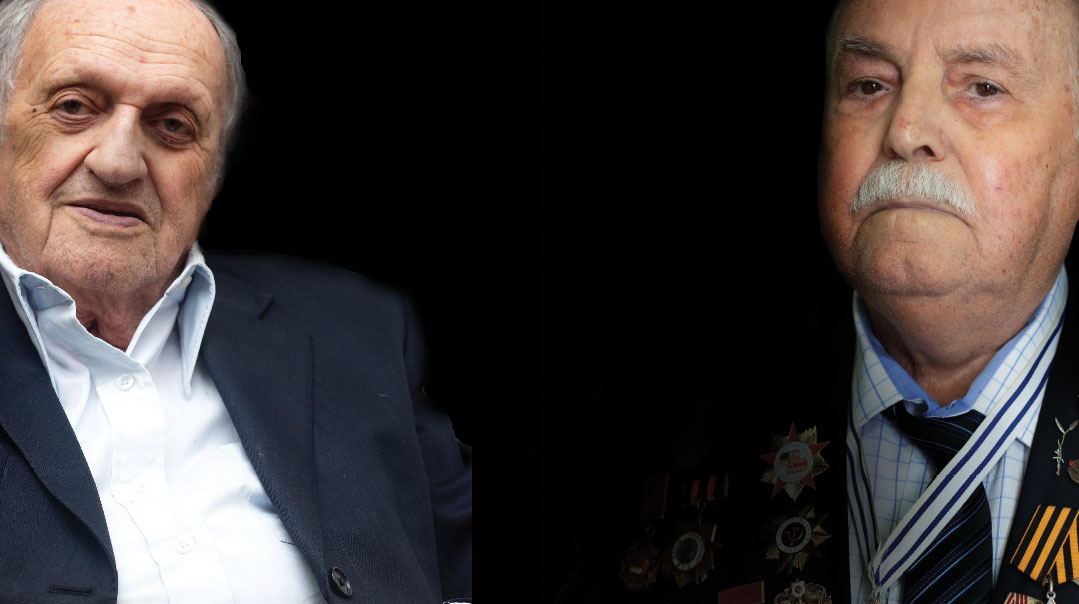

Survivor and Liberator

75 years later, they’re still two bereaved boys who saw the world crumble

The date is seared into Dov Landau’s memory like the numbers on his arm.

On November 5, 1943, a convoy of cattle cars with a batch of human livestock arrived at the rail platform of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Half-choked by the fetid smell, faint with thirst, and avoiding the corpses of those who’d died on the horrific journey, out stumbled 13-year old Dov Berish and his father, devoted Bobover chassid Reb Binyomin Landau.

There on the railway platform young Dov’s childhood ended. He learned that here in this new existence, even next to his tall father, he was utterly alone. “The SS began beating us and shouting ‘Schnell, schnell,’ while their dogs strained at the leash. And my father couldn’t say anything to me — it was each person for himself.”

A little over a year later, another Jewish boy arrived in Auschwitz. Like Dov Landau, Max Privler was born in Yiddish-speaking Poland, and like the son of the Bobover chassid, this child of wealthy landowners also had his comfortable childhood shattered.

But unlike Dov, Max wasn’t there as a prisoner: Just 14 years old, he entered Auschwitz as a liberator. At an age when most kids are figuring out how to cut class, he was one of a small number of child-soldiers in the Red Army, operating deep behind enemy lines on intelligence missions.

Despite his baby face, this Jewish boy was a hardened Nazi-killer, driven only by thoughts of avenging his murdered parents. “The other Russian soldiers drowned their shock in drink when they came to Auschwitz,” he says, “but I’d already seen such tragedy that I had no choice but to go on.”

At first sight, these two men’s extraordinary lives mirror each other. Dov Landau holds up his concentration camp uniform, while Max Privler wears a formidable array of Soviet medals. One is a survivor, the other a liberator.

But the pictures crowding the walls of Dov Landau’s Tel Aviv home tell a different story. Reaching pre-state Palestine, he fought the Arab Legion in 1948. The survivor became a fighter.

And as Max Privler stands in his Bat Yam apartment in his Red Army uniform, the memories of the three mass killings he escaped will never leave him, nor will the scar of the bullet wound in his back. Beneath the liberator hides a survivor.

And in a heartrending way, there’s something else that they share. Seventy-five years after the liberation of Auschwitz, as dozens of world leaders have converged on the Jewish state to condemn the Holocaust and global anti-Semitism, these elderly men’s voices crack as they speak of the mothers they were torn away from as young boys.

“Mama,” they say, and decades later, it’s still an 11-year-old’s cry of pain.

“I remember like yesterday the brachah of the Kedushas Tzion of Bobov,” says Dov Landau in an Ivrit sprinkled with a rich Polish Yiddish. “It was Rosh Chodesh Nissan, 1935, and I was seven years old. The Rebbe came for the sheva brachos of his relative, and my father, who was a close chassid, offered to give the Rebbe our house while we moved in with our grandparents.”

Eventually the visit drew to a close and it came time for the Rebbe to say goodbye. “He sat on my father’s bed wearing a golden caftan, crowned with his fur kolpik, and gave me a zloty coin. He put his hands on my head like a Kohein and said Yevarechecha.”

The Rebbe didn’t survive the war, but his blessing did.

Eighty-five years have passed, and in his small Tel Aviv apartment near Kikar Rabin, as Dov Landau remembers that long-vanished world, there’s a small part of him that’s still there in Poland of old.

Born the eldest of four sons in Brzesko, a shtetl between Krakow and Tarnow, to Binyomin and Sheindel Landau, baby Dov entered a world of material comfort. His father owned a clothing store and two houses in the town that the Landau family — descendants of the Nodah B’Yehudah — had called home for 150 years.

There was another sign of pre-war wealth: a beautiful leather-bound Shas that Binyomin Landau received as a chassan. And in a tale of survival that mirrors his own, Dov today holds the volumes embossed with his father’s name, a physical link to his lost parents.

The Landau’s prosperity was matched by their chassidic warmth. Having spent four years as a bochur in the court of the Bobover Rebbe, Binyomin was a fervent chassid, and with his strong, melodious voice, was the baal tefillah in the local Bobover shul.

Dov’s own voice — still strong at 91 — fills his living room as he waves his hand gently and imitates his father. “Kol mekadesh shevi’i,” he sings, with the tune that spread from Bobov to Shabbos tables across the world.

For a moment, as Dov reminisces, he’s back with Yossel the wagoner who drove the Rebbe, and with Baron Getz, the local magnate in his princely carriage who came to greet the Jewish leader in the hope of getting his political support; and he’s wearing with pride his own dashik, the little velvet cap that marks him out as the big boy, older than brothers Naftali, Yosef, and Nissan.

But like those golden years, the moment comes to an end. Dov’s voice thickens as he describes a child’s view of the unfolding destruction.

“The war came as a surprise to me,” recalls Reb Dov, “although I remember soldiers breaking into my father’s shop to steal civilian clothes in order to desert. Just after they had fled, the Germans marched into the town square.”

If young Dov had been unaware of the rising anti-Semitism emanating from pre-war Germany, in September of 1939 he was quickly robbed of his innocence. “The town’s main shul was opposite our house, and I saw the Germans place the sifrei Torah in the middle, pour in benzine, and burn it down.”

Busy subduing Polish resistance until the end of the year, the invaders didn’t immediately move against the Jewish community once they’d torched the shul. But at the beginning of 1940, the Germans chose 12 leading Jews — including Binyomin Landau — to form the Judenrat, the tool with which they’d control the town’s community.

The local Gestapo head was a barbarian, shooting Jews on sight who couldn’t answer in German. It wasn’t long before Jewish life in Krakow descended into constant fear.

Dov recalls his own bar mitzvah under the clouds of impending disaster. “Shabbos Nachamu 1941 it was my bar mitzvah. My father got some family and friends to come to a seudah, and we tried to celebrate. My mother was a very good cook, and she made pots of cholent and kishke, liver, galeretta, and all of the Shabbos delicacies, but there was a very subdued atmosphere,” recalls Dov.

By the next week, Dov was a grown-up under German law as well. He had to report for forced labor along with all others aged 13 to 65, packing bundles of hay for the German cavalry, in a camp two miles outside the city.

The Landau family had so far escaped relatively unscathed. But a year later, in Tammuz 1942, things worsened when the Germans demanded a massive bribe from the community as the price of “protection.” This was a standard method of systematically despoiling a Jewish community targeted for liquidation, but the Krakow Jews still hoped that they could satisfy the Germans with this offering.

As a community official, Binyomin Landau was responsible for collecting the quarter-million zlotys and expensive furniture the Gestapo demanded. Scared that his family would suffer for his prominent role, Reb Binyomin sent his youngest sons to Bochnia, where his parents-in-law lived, soon to be followed by his wife Sheindel.

Dov volunteered to help his mother prepare the Shabbos food for the journey. “I said to her, ‘Let me help you so you can get to Bochnia quicker.’ In the middle of cooking, she sent me to the store across the road to get a kilo of flour for bread.”

That was the last that the young boy ever saw of his mother. “I came out of the shop, and suddenly I saw the square was filled with SS, barging into Jewish houses with drawn guns.”

Terrified, he approached the door of his home, and then the Germans spotted him. “They shot after me as I started running, and the bullet went between my legs. I ran all the way out of the city to the labor camp where I worked, and when the other laborers asked me what the shooting was, I told them what had happened.”

That evening Dov and his friends headed back home, only to find a ghost town. There were lots of bodies lying in pools of blood, and his mother was gone.

A non-Jewish family friend found Dov shaking with fear and asked, “Are you Binyomin’s son?” It turned out that on his way to deliver the community bribe to Gestapo headquarters, Dov’s father had heard what was happening and managed to hide in this friend’s house in a village outside the town.

An hour later, father and son were reunited. They hugged and kissed, and together went back to their home, where the seforim had been thrown all over the room by the German killers.

Desperate to track down his wife, Binyomin Landau hired a Polish woman to follow the train that had left carrying the deportees. She met the train’s driver, who told her that Krakow’s Jews had been shipped hundreds of kilometers to the east, to Belzec. By that stage of the war, no one believed Germans tales of “resettlement” — it was clear that they’d gone to their deaths. “I don’t know how we knew what was awaiting them — how that information spread — but we knew,” he says.

The war was in its third year, and his beloved mother had gone, but Dov Landau still had his father. In mid-1942, the Jews of Brzesko were forced into a ghetto, and Binyomin Landau decided to escape his hometown. As a Judenrat member, he had a travel permit, and so father and son travelled to Bochnia, the largest remaining ghetto in the region, and where Dov’s two younger brothers had been sent a few months before.

“I can’t describe what it was like in that ghetto,” he says, clearly taxed by the narrative as he gets up to brew some tea. “There was a feeling of total fear. There were food shortages and everyone trying to survive in some way.”

It was a year later, coming up to Rosh Hashanah 1943, that the Germans decided to clear the ghetto. Knowing their fate, many decided to ignore the selection that would determine whether they were shipped to labor or death, and instead hide in primitive bunkers.

The ghetto had some 30 rebbes, among them Rav Yisroel Spira, the Bluzhever Rebbe, and before he escaped via Hungary, the Belzer Rebbe. “I saw the Tshechoiver Rebbe, Rebbe Shayale Halberstam, hide inside a bunker with another two dozen men. When the Germans discovered their hiding place, they threw a hand grenade inside, and all of them were killed,” he says, shuddering as if the horrific scene is still in front of his eyes.

It was a Shabbos when Dov Landau arrived in Auschwitz, but that was an irrelevant fact belonging to a past life. Home life, chassidim, mother — he’d shed them all on the road to this nightmare.

Of the 40 freight cars containing 4,500 Jews who’d been taken from Bochnia, many didn’t survive the inhuman conditions of the journey. But Dov and his father did, and they emerged into the world of Auschwitz together.

“The first thing I saw was the SS with their dogs, their shouts and barks mingling. Then I saw Mengele. We were lined up in rows of five, and as we approached the selection line, I had a feeling of fear,” remembers Dov Landau. “Mengele hit me on the hand to go to the right, and my father was sent to the left. He didn’t know what that meant, but looking around at the old people, he sneaked back into my line. My father was six feet tall, so he had to stoop to blend in.”

But in this world of Nazi efficiency, that decision had consequences. Mengele’s administrative report, which lies in front of us as part of the thick file Dov has from German records, details in clinical language that 952 men were chosen for forced labor. “The remnant,” Mengele wrote, “I sent to the gas chambers.” When Binyomin Landau escaped back into the temporary reprieve of the column to the right, another victim had to be found.

“Mengele dragged another person by the hair from the right to the left,” says Dov.

Sent to Birkenau, the part of Auschwitz dedicated to working Jews to a slow death instead of gassing them, the young prisoner saw the industrial scale on which the Nazis operated. Equally shocking was the meaning of the number branded on his arm. “It had a letter ‘P’ for Poland, and my number was 161400. Imagine how many had come here before me?”

It was now November, and the harsh Polish winter was setting in, with 420 men housed in a hut without water or heat. By day they performed backbreaking labor, dragging rocks to build roads manually. And by night, they had to shiver in their thin striped uniform, on hard wooden shelves suited for stacking logs, not people.

“People froze from the cold. I got a liter of watery soup and a bit of bread, but then I got dysentery so I stopped eating the soup,” says Dov.

But worst of all was the latrine hut. Meant for 150 people, this deliberately dehumanizing, open area horrified the young teen. “All our self-respect went in this way, as our clothes got soiled.”

“It’s hard for me to describe,” he says, “but each person looked after himself, and the only thought we had was what will be tomorrow.”

On the other side of Auschwitz-Birkenau’s vastness lay the crematoria and gas chambers, but Dov was spared that — for the moment. After a month, Dov and his father were taken to Yavishovitz, a coal-mining labor camp and part of the vast slave empire that the Nazi war machine depended on.

“We had to walk two kilometers each day to the mines, which were deep underground, and supplied by workers from Birkenau,” Dov remembers. “I was told to work with a Polish foreman, and my father was assigned backbreaking work on the night shift.”

But after two months, it was the older, stronger man who broke. Reb Binyomin got ill and couldn’t work, so he was taken to the “clinic,” a cruel name for a hut with no medical facilities. When he showed no signs of recovery, the Germans decided to send him away to a “sanatorium.”

“He’ll come back when he recovers, they told me, but I didn’t believe them — I knew that they meant a crematorium, and so I tried to jump onto the back of the truck with him. But then my father looked at me and said, ‘We’re now separating, and I have a feeling that you will survive. Du velst iberleiben di gehinnom,’ he said, and after giving me Bircas Kohanim, he uttered his final words: ‘Please remain a Jew.’ ”

For millions of others, the path that the boy from Krakow had taken led, sooner or later, to the gas chambers. But this particular young man, as his father predicted, was destined to survive, and Divine help took the form of an unlikely angel: a burly Polish coal miner.

“I continued to work in the coal mines, but while others wasted away, I had good food. The Polish foreman took mercy on me, and he brought an extra sandwich every day for me to eat. His wife baked a round bread, and put on a shtikel davar acher,” says Dov Landau, not wanting to mention the treif meat he’d eaten in order to stay alive.

“It was pikuach nefesh, so I ate it in order to survive. Every day at 10 a.m. we sat and ate those sandwiches and drank tea from his flask. That gave me the strength to endure what came next.”

It was a death march. As the Russians approached in January 1945, a teenaged Max Privler among them, Dov Landau was driven, with four thousand others, along like sheep. Flanked by the SS and their dogs in below-freezing temperatures, they marched day and night, without rest, covering 63 kilometers in six days. But with the Soviets in hot pursuit, the retreating Germans decided to ship the exhausted survivors by train to Buchenwald, in Germany itself. Thirteen of Dov’s friends froze to death in the open boxcars — a small portion of the 2,000 who didn’t survive the journey.

With his extra strength due to his daily sandwich, Dov was put to work unloading the dead when they arrived at Buchenwald on January 22. He was placed in a hut with older men, one that has been preserved for posterity in an infamous picture of emaciated mussulmen. He was soon transferred to a children’s barracks, and set to work in a gravel quarry.

A few months later came the sweetest music in the world, the melodious growl and thunder of American planes and artillery pounding the fleeing Germans.

“I was 16, and I knew that we were saved. While many were scared to go outside, I wasn’t,” Dov recalls.

It was April 11 when the first US jeep, containing four soldiers, entered the nightmare scene of Buchenwald. One of them, a tall Jewish soldier, was surprised when the emaciated Dov picked him up in the air. “I jumped on him like a lion. You know who it was? It was Lieutenant Birnbaum.”

That relationship remained for many years. Just two days before our interview, Dov Landau was in Jerusalem, at the shivah for Goldie, Lieutenant Birnbaum’s almanah, where he spent several hours recounting his eyewitness stories to the next generations of the Birnbaum family.

Just after liberation, Dov himself saved someone — a young boy who went on to become world famous. Just hours before freedom came, he was outside and saw someone faint. Unable to pick up the ill man on his own, Dov asked a friend to help bring him to the SS hospital.

The man went by the name Tulek, and he asked Dov to bring him his younger brother, Lulek.

“I went looking for the little boy, and saw a tall, blond, non-Jewish inmate baking him potatoes. I said, ‘I want to take him back to his brother,’ but the man, who had taken Lulek under his protection throughout his time in Buchenwald, only agreed on condition that I promised to return him.

“By that time Tulek was lying in the typhus ward, so I lifted up his little brother so that they could see each other through the window. Then the older man said, ‘Berish, listen — I don’t know if I’m going to live or die, but don’t give the child back to this non-Jew. Look after him, and take him to Eretz Yisrael, and bring him to my uncle Rav Vogelman in Kiryat Motzkin.’ ”

A week later, the angry would-be guardian demanded to know where the child was. Tulek was already on the road to recovery, and answered unequivocally that the child was accompanying him — and that’s how Israel gained one of its most famous figures.

Because the child Dov Landau saved from Polish adoption went on to become Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau.

Dov Landau’s life after reaching Israel is enough to fill another book. He graduated high school and was drafted into the pre-state Haganah, where he fought the Arab Legion in Gush Etzion and spent a year in Jordanian captivity. Upon his return, Dov met and married Shoshana, the sister of a close friend who had fallen in the fighting. Shoshana passed away several years ago.

Looking around at the walls of his apartment, the past meets the present: Pictures of the Bobover Rebbes are next to those of his grandchildren — many of them high achievers in their professions, and all religious.

Today, his greatest joy is to get together with others and sing his Bobover tunes both in his Tel Aviv shul, and also in front of groups of young olim for whom he’s often called on to speak at communal Shabbos dinners — his strong voice spreading waves of old-time Jewish warmth over these young people whose upbringings in New York and London are a world away from his own. In fact, 91-year-old Dov Landau is now on the road again, between Tarnow and Auschwitz, to take part in the Polish government’s commemoration.

But during our conversation, as Dov Landau gets up to stir his tea, he’s gray-faced, and the eyes that normally twinkle are clouded over. “My father wanted me to remain a Jew with all 248 limbs,” says Dov simply, “and that’s what I’ve done.”

If you stand on Ort Yisrael Street in Bat Yam with your eyes closed, you could be mistaken for thinking you were nearer Moscow than Tel Aviv.

There’s a head-scarved babushka hanging washing out of a crumbling apartment window; young and old are speaking Russian; and a display in the lobby of Ort number seven shows at least 20 lavishly-beribboned Soviet war veterans. Taking the elevator up to the tenth floor, I half expect the loudspeaker to play “Kalinka,” sung by the Red Army choir.

This is as good a place as any to discover a liberator of Auschwitz, because it was the Soviets who overran Auschwitz on January 27, 1944. And here in Bat Yam, I do indeed discover a startling new narrative of someone who survived mass killings, fought as a partisan, and finally entered Auschwitz as a 14-year-old liberator.

Like his contemporary Dov Landau, life was good for Max Privler, born in 1931 into a religious family in Mykulychyn, near Stanislav — then Poland and now Ukraine. The family — known then as Privler-Hershkovits — had been in the area for generations, and were wealthy landowners. “My grandfather owned land, forests, mills, and factories,” recalls Max Privler, obviously delighted to speak in mamma loshen, a slow, slightly rusty Yiddish. “They built the main shul in the town, and their purebred steeds were only available by order, and only for the Russian army high command.”

This was real shtetl territory, and despite the Jews’ ancient presence in the area, old hatreds ran deep. Bogdan Chmielnicki, the Ukrainian instigator of the Cossack massacres known as Tach V’Tat, which wiped out Jewish communities in the mid-17th century, was from the area. The locals were so feared that even Mongol warlord Genghis Khan was said to have avoided the region due to its savage reputation.

As suddenly as war hit the Landau family in Krakow, it took the Privlers by surprise in Mykulychyn. The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact seemed to shelter the USSR from war — until Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s surprise attack on Stalin’s empire.

At the beginning of July 1941, Hungarian troops occupied the city and started to loot Jewish-owned stores. But a few weeks later, the Germans arrived, and a reign of terror began. “They forced us to wear a yellow star, we had to move into a ghetto, and those who didn’t get off the sidewalk were shot dead on the spot,” says Max Privler.

Through an 11-year-old’s eyes, Max recalls his feelings. “We were scared, but our parents had no choice but to go out to work — walking because they were forbidden to use public transport.”

Max says his family was kept alive because his father, David Privler-Hershkovits, a prominent businessman, owned a wood factory, and he was instructed to oversee it being dismantled and sent to Germany. After that, Max’s mother and brothers were separated and thrown into the ghetto, while he was locked up together with his father.

Max’s world was shattered when his father was murdered in front of his eyes.

“The Nazis took us both away to a mass grave along with a thousand Jews where we had to undress. My father stood in front of me on the edge of the grave and placed me behind him. Then he said to me, ‘If you survive the war, tell the world what the Germans did to us because we were Jews.’”

Those were David Privler’s last words. In the hail of gunfire, a bullet ripped through his father and entered Max’s shoulder, where it lodged for the next 27 years. The boy toppled into the grave, blood streaming from his wound, where he lay until nightfall.

Climbing out, he made his way to a neighbor who had been a friend of his grandfather. But Max hadn’t accounted for the local anti-Semitism, even from someone who had been well-treated by his family. Taking one look at the child who had come back from the dead, the neighbor kicked him in the chest.

At the house of some more compassionate Ukrainians, Max was allowed in to be washed and bandaged, and his clothes changed. They then gave him a letter saying that he was an orphaned Ukrainian boy named Yurko Yeremchuk — and he was sent on his lonely way in the world.

It was now 1942, and Max found another family to adopt him — his looks and command of the language enabled him to pass himself off as a Ukrainian. After surviving the first mass shooting, the same happened twice more. Max glosses over those occasions, and instead talks of how he wanted to get into the Stanislav ghetto to see what was left of his family.

Max was able to smuggle some food and shirts from his host family into the ghetto, but on one time inside he suddenly saw his mother, sister, and younger brothers manhandled by the Germans.

“I went into the ghetto, and saw the Germans snatch away my youngest brother Berele, who was just a baby, from my mother’s arms,” says Max. “My mother resisted instinctively — she pushed the German soldier and he fell backward, breaking his skull. Then the Germans crowded around and killed the baby, and then took Mama off to their headquarters where they hanged her from the second floor.”

Max’s voice shakes, and a look of pain crosses his face as he relives the terrible moments when his world collapsed around him. “I ran away like a meshugener, crying “Mamale! Mamale!”

But his headlong flight was interrupted by another Jew who stopped him and told him, “Don’t be crazy! Wait and have your revenge!”

It was a dream that led Max to the partisans. His host family assumed the young boy was a Ukrainian like them, until he went with the father to transport some sacks of flour. Suddenly some partisans jumped out of the forest and demanded the food at gunpoint.

Young Max watched as they retreated into the forest, and then, as the two of them rested before returning home, he fell asleep. When he woke up, his host accused him of being Jewish. “You were speaking Yiddish in your sleep! I’m going to report you to the Germans!”

The man left to carry out his threat, and Max disappeared into the forest where he’d seen the partisans go. No more than few minutes in, he was grabbed in a chokehold from behind by a partisan who demanded, “Who are you?”

Max was locked in an underground bunker, and was released by the chief partisan, a Jew. It turned out that he knew Max from the ghetto. Then the tears came to the young boy. “I cried so much to see people from my past,” says Max.

The very next day, the boy’s partisan initiation began, as he went looking for a weapon. “I waited next to the road when a German dispatch rider came along. He stopped his motorbike and took out a cognac bottle to have a drink. I saw that he had a very good rifle with an optical scope — the best of the best.”

Brave as this 12-year-old was, Max couldn’t tackle a grown man barehanded. But as the German drank, he lost his balance and toppled into the fast-flowing stream.

“While he was dragged downstream, I fished out his gun with my suspenders,” says Max, “then I hid it in the forest.” Returning to the partisans, he waited two days to bring back the precious rifle and magazines, and then joined the partisans’ operations.

But in the cut-throat world of the partisans, there was no rest for the weary — even from those on his own side. “After a few months with no winter clothes, I froze. I was told that I had gangrene, and I was going to be killed because I was a burden on the group.”

Then help came from the heavens, in the form of a light plane belonging to the Red Army. A medic had arrived to treat a senior partisan. He took pity on the dying boy laid out in the snow, put him in the plane, and transported him to a hospital in Russia. “That was in November of 1942,” says Max, “and I’m still looking for that medic today.”

In any other part of the world, someone Max’s age would have been sent to an orphanage. But in the unforgiving war conditions of the eastern front, someone thought that the boy who spoke five languages would make a good spy.

“I was drafted into military intelligence and sent to a training school in Kursk to learn about surviving behind enemy lines,” says Max. “We watched trains to track German military movements, we were able to infiltrate large ammunition depots and give the coordinates to artillery who destroyed them. No one suspected us because we were children.”

Despite the anti-Semitism that riddled the Soviet army, his fellow soldiers treated him well, given his value as a spy. At the tender age of 14, he was valuable enough to the army to be assigned a driver and officer’s privileges.

Using the stealth that he had learned, he entered Kiev. Ambushing the last German car in a convoy, he killed the occupants and disguised himself as a German. Where did a boy find the strength to kill? “I was alone and had no choice but to be courageous and clever. Besides, I had a tremendous desire to take revenge,” he says.

That thirst for retaliation only grew as the Soviets beat the Germans back across Russia, and Max discovered that Europe was nearly judenrein. “There were lots of Jews in the Soviet army, but I hardly met any Jews in the places we liberated — they had all been killed.”

By that time Max was on a rampage to avenge the blood of his brothers, and although he was just a teenager, he received a medal of honor for his bravery in the battles across Poland from January 18-22, the week before Auschwitz’s liberation, where he “showed unusual courage… with his actions he saved his unit and killed 25 enemy soldiers, including two snipers.”

In fact, it was a Jewish officer by the name of Anatoly Shapiro who led the advance into Auschwitz. “Soviet intelligence knew about the existence of Auschwitz, but it wasn’t a military priority. Major Shapiro persuaded his commander to take the camp, and he was given command of forces who would engage the SS units and prevent them from destroying the evidence of their crimes.”

Max Privler’s unit approached Auschwitz from the other side in a pincer movement, and that is how the Jewish boy from Poland saw firsthand the horrors that his people had suffered.

“For the first few hours we hunted for hiding SS, but when that was done, I saw the gas chambers, the crematoria, the bags of human hair, piles of children’s shoes, jewelry, and gold,” he recounts.

“Everywhere,” he continues, “there was an awful smell. It was horrible to see them wheeling out these carts full of dead, emaciated bodies. But then we found Jews who were musselmen — we had to hold them up because they couldn’t stand on their own. Those who were still alive, we put on trucks to take to hospital.

“As a Jew, I was so happy to be able to help them. I talked to the survivors in Yiddish. I asked them who had remained alive from their towns, but they said ‘no one.’ ”

Max Privler fixes me with a hard stare when I ask him if there’s a special message he wants to convey to the world. He’s afraid that I won’t get his story right — that his beloved Mama, his murdered Berele, and the father who took a bullet for him won’t be remembered properly — and says so in a burst of agitated Russian.

He’s calmed by a grandson and two great-grandsons who have arrived to take over the work of translation. His stern, craggy face softens when he talks about them. “I’m a millionaire,” says the man who lost everything when he was far younger than they are.

A few days after these two conversations, roads are closed across Jerusalem for heavily-guarded motorcades as dozens of world leaders fly in to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation. Victors and vanquished, heads of powerful states, and leaders of those whose countries were crushed sit alongside each other as the German president expresses his nation’s eternal shame.

It’s hard not to draw parallels between these two 11-year-old boys in Poland — Dov Landau and Max Privler, both survivors and both fighters, seeing what no child should see, clearly protected by a Divine Hand. On the backdrop of dozens of kings, princes, and prime ministers converging on the Jewish state to denounce the Holocaust, these two men — whose experiences have been so divergent over the last seven decades, one living a Torah life in Israel, the other trapped behind the Iron Curtain — have lived out their very different lives with a vision of that one last message from their fathers: Never forget you’re a Yid.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 796)

Oops! We could not locate your form.