Strictly Business

Readers share tales out of the office — perils, pitfalls, and the ways they aim higher

“In my field, networking is everything. I need to build the contacts my parnassah depends on, but the schmoozing at a lot of these events makes me uncomfortable.”

“Navigating workplace etiquette is so tough. I was showing off a picture of my kids and a male coworker commented on how cute my family is. I wasn’t sure how to respond.”

“I had solid hashkafos, I learned concrete gedarim in seminary… until five years down the line, when I’m working in a corporate office where no one has used the word ‘Mr.’ in the past decade. How do I apply the rules I learned to this world?”

“I don’t schmooze in the office with my male coworkers… but then I got a voice note from my male coworker late at night, and felt so uncomfortable.”

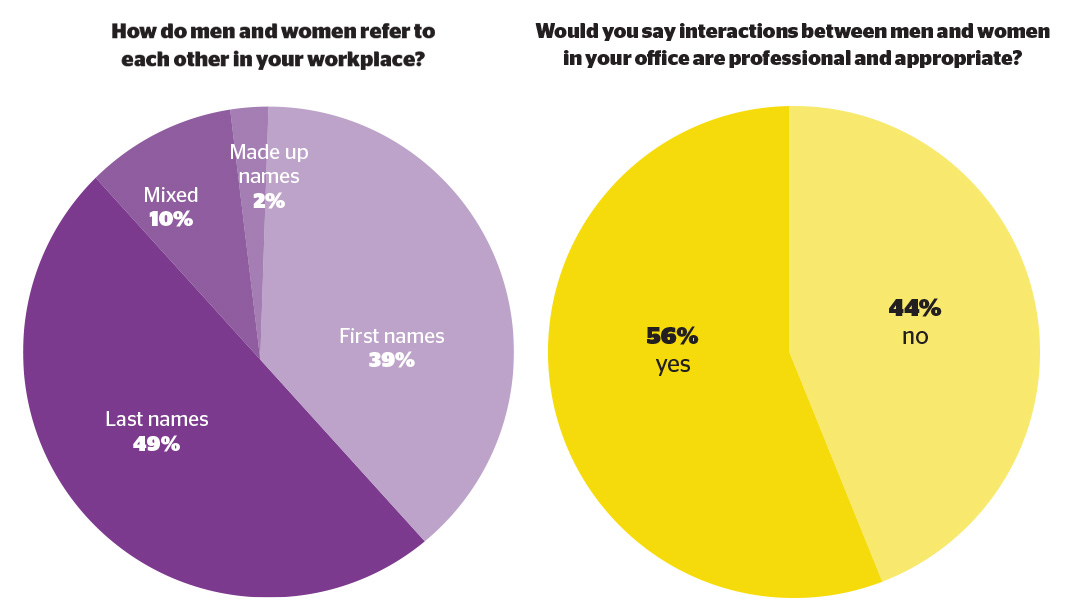

We asked our readers:

You want to support your family. You want to build your career. And you want to do it all the right way.

How do you make it work?

The responses poured in — from bosses, from employees, from a number of organizations that help people navigate the workforce with tzniyus and kedushah. We heard tales of murky dilemmas, breached boundaries, uneasy interactions. But we also heard stories of spiritual splendor and quiet strength, stories that tell of a nation with fierce commitment to its principles.

Here are their stories

Door Wide Open

“DO

you have a minute to talk?” Benzion asked.

“Sure,” I said. “Come into my office.”

I’m the manager of a department in a frum medical supplies business. Our office employs both men and women, and I like to think that we have pretty high ruchniyus standards in place. Men and women sit in separate rooms. Office events and Rosh Chodesh parties are either held separately for men and women, or with very separate seating. Many, if not most, staff members use “Rabbi” or “Mr.” or “Mrs.” when addressing the opposite gender, and the women will cut short any schmoozing about recipes or shopping when a man enters the room.

As a manager, I try to maintain an open-door policy. I want my team to know that I’m here to help them do their best work, and they’re welcome to stop in my office or pop me an email when any questions come up. And I think it’s healthy and positive when a female colleague’s work question occasionally develops into a conversation about mothering tips or Pesach cleaning.

Still, I try to project an air of professionalism when interacting with my male colleagues. I want to be approachable and available for any questions or concerns, but still somewhat crisp and reserved so the conversation stays focused on work.

When Benzion asked to come talk, I figured he wanted to iron out some questions about a big sale we were about to close. But as he sat down on the other side of the desk, he seemed on edge.

“So I wanted to talk to you,” he said, tapping his fingers on the desk, “because — because things are pretty tough for me right now at home. I thought you should know.”

This made sense. A crisis at home can spill over into work, and a manager armed with the right information can provide a struggling employee with support — adjusted expectations, extended deadlines, removing some of the burden.

But what came next made no sense at all.

“So my wife, she’s been dealing with a very serious case of depression for the last few months,” he said.

I nodded. I hear you, I wanted to broadcast, even without words.

“We’ve tried a few different approaches — therapies, medications,” he went on. The tapping on my desk got louder, more strident. “So this new medication, the doctor thinks it’s really making a difference, which is good. But still... my wife just isn’t the same. She’s so... so cold, so distant.”

This time I didn’t nod. I was completely and totally floored. What?

“You can’t understand what this is doing to me,” he went on. “It’s like... I know it’s not the most important thing, she’s still my wife... but everything in our relationship seems so different to me now. She just isn’t the same.”

He must have noticed at this point how frozen I’d become. His voice got softer. “So it’s really hard for me at home. And… I wanted you to know.”

Nothing in my Bais Yaakov education, my seminary classes, my years of carefully maintained “courteous but professional” workplace policy had prepared me for this. What do you say?

“It sounds like you really need someone to talk to, someone who can understand you,” I managed to choke out.

He nodded. “Yeah, it’s hard to find,” he said.

A minute of awkward silence, then another.

He rose from the chair. “So I want to thank you for listening. It’s good to work with people who care,” he said.

“Right,” I managed.

He left the room and left me wondering. For days afterward, I kept replaying that bizarrely, egregiously inappropriate conversation. And I kept wondering: Where did I go wrong, how did I slip up, what previously locked door did I inadvertently open, that a man could feel comfortable walking into my office and talking about his marriage with me?

I’m careful not to email or Whatsapp male co-workers late at night in case it leads to a back and forth between us. There’s an element of intimacy there when you’re the only two people awake and the rest of the country is sleeping that’s inappropriate.

I’ll be honest. On a pretty constant basis, I thank Hashem that I work in a girl’s high school and am not subject to the nisayon of male-female dynamics in the workplace. I have extremely strong principles, but frankly, I’d find it difficult to suppress my personality in a mixed-gender office. I definitely speak my mind, I often have sharp comebacks and funny things to say, and I enjoy talking to all different types of people. I’m so grateful that I have a fulfilling job in an atmosphere free of this nisayon.

Private Comeback

I’D

been working in corporate America for seven years when I received an offer at a frum marketing firm. I was thrilled! I’d had enough of awkwardly navigating coworkers who’d never heard of “Chol Hamoed,” who knew I was taking off for something I called “Tishah B’Av,” but were confused about why I signed out early the preceding day as well, who mumbled awkwardly when informed of yet another maternity leave. Starting to work for a frum company — where everyone not only understood all that but was living it, too — was like one long exhale of a breath I’d been holding for eight years.

The new company was everything I’d hoped for — and more. Our shared way of life meant a shared background and shared standards. Many of my female coworkers were also supporting husbands in kollel, while many of the men had spent years in kollel. Men and women were definitely not on a first-name basis, and of course would never share an office room. We also did much of our work from home, through Slack and WhatsApp.

It took some time before I admitted to myself that maybe the new setup wasn’t as ideal as I’d thought — or maybe as I was pretending it was. A good marketing firm crackles with a collaborative, creative energy, and ours was certainly that. One coworker throws out an idea, another builds on it, a third hones the tagline. Our group brainstorming sessions are fast-paced, fun, full of good-natured one-upping and what-iffing.

It was great that we could work from home, but it turns out that in some ways, it’s easier to erode boundaries on Slack channels and WhatsApp chats. In person, in the office, we had physical distance and formality; I’d hover at the door of a male coworker’s office and preface my question with the always-awkward “Mister.” Virtually, it was all too easy to laughing-emoji a male coworker’s quip or dash off a sharp email comeback.

Nothing ever “happened.” But a few months down the line, as I laughed at an incoming email and prepared to hit reply with my own quip, I realized what I’d been hiding from myself: We may be using last names only, writing on group emails only, makpid on yichud l’chumra, but bottom line: I was friends with the men I worked with.

After an uneasy, sleepless night, I realized I needed to recalibrate and pull way back, awkward as it was. I still participated in company meetings, of course (in person, via Zoom, and over Slack), but now I kept those snappy comebacks to myself. My replies were measured and thoughtful; I still shared compliments and feedback, but now I wrote them out in full sentences — no LOLs or “love it!”

It’s been a few months now, and honestly, they’ve been awkward — I went from being one of the chevreh to the slightly stuffy, mildly awkward one. I no longer get the rush I once got from those fast-paced, fun brainstorming sessions. But I’m proud to say that me and my male coworkers? We’re no longer friends.

Who Am I?

T

entatively stepping my foot into the corporate world, paperwork was much easier to fill out with my legal name, and who could pronounce the “Ch” anyway? Eva, all the way, it would be.

The workplace is a complicated place. Do I do everything right? For sure not. Do I wish I had my own personal rav telling me what to do every minute in the office? Can’t say I don’t. But in a certain sense, my legal name turned out to be the biggest blessing. My male coworkers don’t call me Ms., but they also have no idea what my real name is. I have a label: Eva. I respond to it. I answer to it. But it’s not me. It’s a separation between my home life and my work life, reminding me that though I love what I do, it’s just work. Professional. Boundaries. Separate.

So who am I? Am I Chava? Am I Eva? Or is this just an adult identity crisis in the making? The Eva and Chava are woven together, a tapestry of all the facets of me, myself, and my personality. Eva is my work life: professional, polite, kind, yet distant. Chava has a sense of familiarity, of comfort, of coziness. I am Chava, and I am Eva, but ultimately, I am a servant of Hashem, trying my best to do what’s right. And when it comes to any area of life, whether I’m called Chava, or I’m called Eva, that’s exactly whom I want to be.

Mrs., Please

“OH,and one more thing,” I heard myself say to my new boss, despite the humiliation, “my husband’s rosh yeshivah is makpid that a married woman is referred to as Mrs., not by first name.” I silently prayed that my new boss heard my words louder than my pounding heart. Luckily, he was an open-minded and understanding Satmar Yid, and he respected my request to call and be called by surname. Which was relatively easy in our all frum, four-employee company.

Twelve years later, we’re 70 administrators, the vast majority of whom aren’t Jewish. Miraculously, I no longer need to repeat my lines. Although I haven’t seen a sign or memo, new employees just know. And the effects of this seemingly simple early employment decision are far-reaching. My title has provided the perfect solution and protection for my family and values. Male coworkers are hesitant to personally engage with someone they can’t call by first name. Yes, we’re professionally amicable, but together with my title, there is an unspoken message that everyone seems to get. I have professional esteem and there’s a pleasant work atmosphere without the slightest twinge of discomfort. I’m so grateful that I heeded the advice and tumbled out that message all those years ago.

Perfectly Professional

I’M

a female psychologist and one of my therapy externship placements was at an all-male residential facility. After extensive discussion with my husband and our rav, I went ahead with the placement and was successful, baruch Hashem. I had lots of nonnegotiable overt and covert gedarim in place: I exclusively wore tichels instead of a sheitel, which always signaled religiosity to the clients, and was very sparing with makeup; I got accommodations for yichud (an office with a window in the door); I was stricter than I would normally be about not disclosing personal information to the clients; I didn’t participate in facility events; I avoided entering the residents’ living quarters, even the auditorium; and I ate lunch alone or with the mixed group of trainees, even though there were lots of free kosher snacks in the cafeteria.

It also helped to praise clients’ actions rather than compliment them, since compliments can get overly personal. When clients tried asking me personal questions (“Where did you get that scarf?”) I kept my responses short and returned to the topic (“I bought it online. So how was that conversation with your parents?”)

I’ve also always been careful about sharing personal information with male colleagues. I’m always cordial and polite, but I make it clear that I’m not looking to make friends. I’ve also found that being shomer negiah has helped a lot with that. One of my best supervisors was an older non-Jewish man, who often told me how highly he respected frum Jews who stuck with their values, and that he appreciated how professional I always was.

I never use emojis when chatting with male coworkers.

Disquiet on the Home Front

S

hortly after I got married, I had a work-from-home job as a computer programmer. It wasn’t a Jewish company, but I thought it would be a tzniyus, appropriate job for me, especially since it was work from home.

A few months after I started, the company announced that our group would be having an annual in-person meeting at a hotel in Las Vegas. I wasn’t thrilled about going, but it seemed to be a requirement of the job. My husband had just started a new job so he couldn’t go with me, so I took a single friend along.

I had a schedule emailed to me before the meeting. It said that breakfast the first day was optional. We arrived the night before the meeting, and one of my coworkers contacted me to say they were all going out, did I want to join? Obviously, I wasn’t going to go out with a group of people like that in Las Vegas; it wasn’t even an option.

The next morning, my boss called my cell phone and asked why I wasn’t at breakfast. I was surprised by the call; it had said it was optional on the schedule they sent out before the trip. I’d brought kosher food with me and my friend and I were eating in our room. My boss seemed surprised by my response, but said he was looking forward to seeing me at the meeting.

I went to the ladies’ room outside the meeting hall before it started. There were coworkers there in various stages of being sick because they drank too much the night before.

I went to the meeting, and my boss cornered me, saying he was disappointed that I’d missed breakfast. I apologized, even though I didn’t think I needed to, and I said half-jokingly, trying to lighten the mood, that it was a good thing I didn’t go out the night before since I was bright eyed and wide awake for the meeting. He looked at me and said that my lack of participation the night before spoke to “a lack of camaraderie” with the group. In other words, he was happier with the women throwing up in the bathroom than with me coming alert to the meeting.

At the beginning of the meeting, we went around the room and introduced ourselves. I was shocked at the lifestyles they lived. And this was a group of people mostly in their thirties and forties!

Needless to say, I left that job, not immediately after, though it was the meeting which signaled to me that this wasn’t the job for me. It was so eye-opening that even a work-from-home job could be problematic.

False Security

I’M

fortunate to work in a fully frum environment. But I’ve had my moments when I wonder if the formal gedarim of “no first-name basis” and separate workspaces lull everyone into a false sense of security.

I probably felt it most when, after my return from maternity leave, I submitted a really creative piece of work for a new project our team was producing to the former kollel yungerman who was leading the project. “Wow, amazing job,” he said. “Must be all those postpartum hormones unleashing your creative spirit.”

You know, all our boundaries are still in place and we check all the boxes for the frum workplace protocols, but since that comment I always view him differently. And I wonder how much the formal protocols help when the underlying sensitivity just isn’t there.

When writing to a man, I wouldn’t use acronyms like tty.

As someone who needs to fundraise and work with many vendors, I attend many networking events. I wanted to ensure that boundaries remained firmly in place for me, and so I set myself two personal boundaries: 1) I don’t eat or drink anything outside of water and fruits/vegetables at any mixed event. This ensures a certain level of discomfort, which is just the right formula for me. 2) Even when I do eat or drink, I don’t sit at a mixed table.

Naive to a Fault

AS

the oldest of a large family, I’ve always had a special relationship with my youngest sister, Brochi. There are 17 years (and six boys) in between us, so on the one hand, we share the bond of the only two girls; on the other, she’s just a few short years older than my oldest! We’ve always been close, and my sister has often turned to me for advice, especially throughout her time in shidduchim, but I try not to take on too much of a motherly role in our relationship. She already has a mother (and I have no other sisters!).

So when I noticed that my sister was sharing less with me, I didn’t prod. She was married less than a year, I reasoned, and juggling a lot: a new husband, a degree program, a new job — and I was pretty sure that she was expecting. (What? I said I tried not to mother her; I never said I wasn’t nosy!) It was only natural that she’d pull back.

It bothered me, though, to see my sister grow more… tense? Withdrawn? I couldn’t put my finger on it, but something was definitely wrong. Still, though, I never said a thing — just reminded her that I was always there if she needed anything, and dropped gentle conversational openings if she was looking for one.

“What you making for supper?”

“Stuffed zucchini boats and grilled chicken.”

“How’s work?”

Shrug. “You know… work.”

“How’s Eliyahu doing?”

A spark of animation. “Oooh, amaazing, what do you think I should get him for our anniversary? Is a tie nerdy?”

Whew. At least they’re happy.

I guess I can’t say I was shocked when Brochi called me and asked if we could talk — but I was shocked when she burst into tears just two minutes into our conversation.

Brochi was working in a small heimish office just a ten-minute drive from her home — so perfect! everyone had trilled — one of three secretaries there. Her boss, a well-known man from a respected family, had always been nice… maybe too nice? Brochi recounted how he’d made her feel slightly uncomfortable with his questions and comments: “How was your Shabbos? Still in that newlywed bubble?” but he’d never said anything overtly off, and she chalked up her discomfort to lack of experience and naivete. Still, though, she’d cringe when he lingered in the doorway of her office, or talk to her after the other secretary in her room had left. There was no halachic concern of yichud, since numerous employees could pop in at any moment, and often did, but Brochi always felt horribly self-conscious whenever it happened. But there was nothing wrong, she’d remind herself… and he was her boss, and everyone was always saying how lucky she was to work for him. So she kept up the conversations, blushing, waiting for them to end.

And then, that afternoon, as Brochi was on her way home, her boss waylaid her by the door and made a comment that was objectively inappropriate by any standard. Shocked, flustered, Brochi muttered something and fled.

Now she was on the phone with me. “I can’t!” she wailed. “I just can’t. I can’t look at him again, forget work there! But what will I tell Eliyahu? I’m so embarrassed. Won’t he be so mad at me? How could he even have done this? Is this my fault?”

On the other end of the phone, I listen silently. I know my role here: listen, hear her out, help her work out a way to extricate herself from the job and broach the conversation with Eliyahu. But right now, I have nothing to say.

I don’t use sarcasm or witty language in a mixed environment.

Remember former VP Mike Pence? He never even had a business dinner with a woman unless his wife was present! It wasn’t enough for him to meet someone in a public place, his wife was there the whole time.

I try not to say “we” or “us” when speaking to a man.

All in a Name

“W

hen we were slaves in Egypt so many years ago,

There was a very evil king, his name was Pharaoh,

He tried to wipe the Jews out, and for that he is to blame

Hashem destroyed his plans because we kept our Jewish names.”

—Uncle Moishy

How many times did my kids listen to that song? Over and over. What was the big deal anyway about Jewish names? They had Akhenaten, we had Moshe. They had Eman, we had Rivka. Why did this merit a Geulah?

As a baalas teshuvah, non-Rebbetzin, I’m not going to pretend I can share what the mefarshim say. Let me tell you that the Jews in Mitzrayim were on to something.

My parents named me Amy. Until I was 20, everyone in my life knew me as Amy. Then, after becoming frum and spending a year in Israel, I got married to Scott. But we did the radical thing without really much thought, and we made the switch to our Hebrew names. My maiden name was Amy, my married name was Chani. Just like that.

Fast forward ten years, and I found myself navigating corporate America. Like… no Jews. None. And I consciously chose to use the name Chani at work. What was I thinking? Why would I do that to myself? The FFB Chanis of the world had no choice. Me? My legal name was, and still is, Amy. Do you know how much easier using the name Amy would have been?

“Hi, my name is Chani. Drop the C and say Hani,” is my go-to intro.

“Oh, that’s an interesting name,” “I never heard that name,” and my favorite, “Oh, it’s like Chanukah/Hanukah.”

Yes. It’s a Hebrew name. Silence. “Oh, that’s interesting,” “Oh, how beautiful,” “Different!”

Different. That’s the key. I’m not like you. You can’t say my name, and that’s super weird, and I’m fairly uncomfortable right now with trying to get you to say my name how it is pronounced and not like how you read it with the hard “Ch.” Or trying to make it French with the “Ch” becoming like an “Sh.” Oh gosh, Amy would have been so much better in this awkward situation.

Would you like to grab drinks after work? No, thanks. (I am different.)

Hey. Some of us are getting together this weekend to celebrate Cristina’s baby shower. So nice! No thanks, I have things to do with my kids this weekend. (Very different.)

We’re meeting the owners today of the company we would like to acquire, and we have reservations at Chez la Treif. Okay, but please make sure that the restaurant is okay with me bringing my container of food with my own utensils. (Over the top different.)

Being different is hard. It’s not natural. Human beings like to fit in. Amy probably would have fit in better. Chani doesn’t. But Chani works hard and is honest and doesn’t gossip and her word is like a written contact. Chani smiles at everyone she sees, she treats the janitor the same way she treats her boss, the CEO, and she judges favorably.

I can’t say that I thought the Chani thing through when I eschewed Amy. But as time has passed, and I’ve climbed the corporate ladder into an executive role, I can now say that was one of the best decisions of my professional life. To speak, to dress, and to act differently. By choice. No matter how challenging the scenario. And I’d like to think that I’m emulating the Jews in Mitzrayim, and doing my part to bring the Geulah.

T

o this day, I’ll never forget the feeling of discomfort I had when my boss leaned over me to do something on my keyboard. He’s very appropriate and doesn’t cross boundaries in any way. It was the only time I felt physically uncomfortable, so uncomfortable.

I use my WhatsApp status and LinkedIn as my social networking platforms. If I notice someone posting too much of their personal life, I mute them. Not because I’m not interested, but because I’m conscious of my purpose on these platforms — strictly business.

I don’t wear eyeliner or eyeshadow to work.

I’m an author and I once worked with a publisher who created a Whatsapp group for me and my co-author to discuss issues that came up. One time I Whatsapped him directly, and he sent me an email saying he was makpid not to Whatsapp a woman directly, only via a group chat. I was very impressed with that geder.

The Right Note

I’M a single girl and I work in the entertainment industry. I was working with popular male singers. My parents were uncomfortable with what I was doing, and they asked me to speak to our rebbe for some guidance and a brachah. I was told not to work with men and that I would see much hatzlachah. It was very hard for me to decline offers, but baruch Hashem, projects with female singers came along.

Here and there, an enticing job came up that was too hard to say no to. But every single time I said yes to a project with a male singer, it always fell apart before it could go further.

I finally got the message. I know I’m doing the right thing, but it’s still hard.

I don’t send voice notes to men

Responsibility & Privilege

AS

a rav with a sizeable network of contacts within the frum community, I am familiar with the challenges endured in the workplace.

I, along with many of my colleagues from different communities, have been forced to grapple with questions that are every rav’s greatest nightmare.

Those who know me know that I am not a fanatic. I do not take extreme stances on issues, and do not align myself with any extreme faction of our community. I say this because the thoughts I will now share may sound extreme to some. But know this. They do not come from a place of fanaticism. They come from experience —mine, as well as that of many other rabbanim.

We have seen too much. And if you haven’t, consider yourself fortunate. You are lucky enough to have not spent sleepless nights because of the heartrending stories making their way to the desks of rabbanim. I don’t want to share the stories, but instead to focus on the lessons and conclusions that are to be gleaned from them.

The very first step is acknowledgment. There have been many open conversations about the challenges of the “secular” workplace. Exposure to an ideology antithetical to ours is detrimental to our spiritual well-being.

While this is true, it only tells half the story.

The frum workplace is not a haven of sanctity. At times, it can present a nisayon greater than that of its secular counterpart.

It is true that the secular workplace sees nothing wrong in male/female interaction, but this can sometimes pose less risk. A frum man shares little in common with a secular woman, which may make it less likely for a real relationship to develop.

In the frum workplace, this isn’t the case. The frum community is incredibly close-knit. Our lives share similar trajectories; we acutely relate to each other’s mindset and lifestyle. Thus, the frum man working aside a frum woman can be more susceptible to forging a connection.

In simplistic terms, the challenge can be summed up as follows: In marriage, a man must earn his wife’s love, respect, and admiration. He must truly care for her and sacrifice for her.

But what’s available in the workplace is something far more convenient.

It allows a man the opportunity to form relationships while offering zero commitment in return. This is a baseline factor in the danger of the frum workplace.

This dynamic is compounded when one or both of the parties in question are struggling within their own marriage. When a man or woman do not feel fulfilled in their marriage, the most natural response will be to search elsewhere, to seek alternative resources and other avenues.

When free socializing between genders is allowed in the office, the answer to the search becomes too easy.

Does that mean that frum offices with both men and women can’t exist? I don’t believe so. But basic gedarim must be implemented to allow the system to work without flooding the desks of rabbanim with horrifying stories. I am not in a position to issue binding rulings but, nonetheless, I write what I believe every rav would fully concur with.

The first and most obvious restriction involves names. While in the secular workplace calling each other by first names is commonplace, this should not dictate the behavior of our community. Frum men and women should not call each other by their first names. Men are “Mr.,” women are “Mrs.”

This is a basic first step toward marking a necessary level of distance and formality between genders.

All the more so, men and women should avoid personal conversations. They can discuss work topics, but should not be having discussions about where they were for Shabbos, what their summer plans are, how their siblings’ weddings went.

Far more precarious than time spent in the office are “extracurricular” events. Mixed corporate parties, without each employee’s spouse present, should have no place in a Torah observant community. It goes without saying that days-long conferences, with no separation between men and women and where spouses are not present, should be seen as unacceptable.

These are general guidelines. But ultimately, it is up to the individual to determine what can and can’t be done. No one knows you better than you know yourself — it is the responsibility, or shall I say the privilege, of the yachid to withstand nisyonos and maintain the kedusha inherent in every Yiddish neshamah.

I will conclude with a note of positivity. We’ve seen challenges before. Heralding every geulah came mountainous challenges — to which many succumbed. We sinned terribly prior to the neis of Purim: we were deeply submerged in the toxicity of Yavan prior to the neis of Chanukah.

But we prevailed. We cried out to Hashem, we did teshuvah, and we were redeemed. Hashem loves us, and if we take that step forward, He will shower us with the greatest blessings.

This challenge, by its very nature, applies to both men and women. The responsibility is upon both of us to work towards a solution.

But history has taught us that women are uniquely capable in bringing about salvation.

In our most dire times of need, it was the women who brought about the salvation. In the merit of the nashim tzidkaniyos, Chazal tell us, we were redeemed from Mitzrayim. Esther was the heroine of the Purim story; Yehudis was the heroine of the Chanukah story.

They did it then, they can do it now.

To the heilige n’shei chayil of Klal Yisrael, I say: it is you who can make change happen.

Rabbi Avrohom Weinrib is the rav of Zichron Eliezer in Cincinnati and rabbinic administrator of Cincinnati Kosher.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 897)

Oops! We could not locate your form.