Story of a Nation

After her husband was killed in Gaza, Hadas Loewenstern shares a message of strength

After her husband, Elisha, fell in Gaza, Hadas Loewenstern’s message to the world went viral, leaving thousands in awe of her faith and strength after such crushing loss. For Hadas, though, it’s simple: This is the story of the Jewish nation. Here, she shares more about Elisha, and the legacy he left her

This is not a private story. This is not about Hadas Loewenstern or Elisha Loewenstern. It’s about the Jewish nation.”

These are Hadas’s words.

Of course, it is true. Hadas continues to proclaim that this is a cosmic, global battle: good against evil. It’s a historic battle, another chapter like so many in our nation’s history.

But it’s also incomplete.

Because this is also Hadas’s story, and the story of Elisha and a marriage and a family.

And it’s the story of how the personal and national interweave, how all of us play a part in the great tapestry that is the story of Am Yisrael, across oceans and eras.

Two Pictures

My first introduction to Hadas was through two pictures:

The widely circulated family portrait: Elisha and Hadas, both with big, beautiful smiles, surrounded by their six children. The youngest a baby and the oldest a boy of 12.

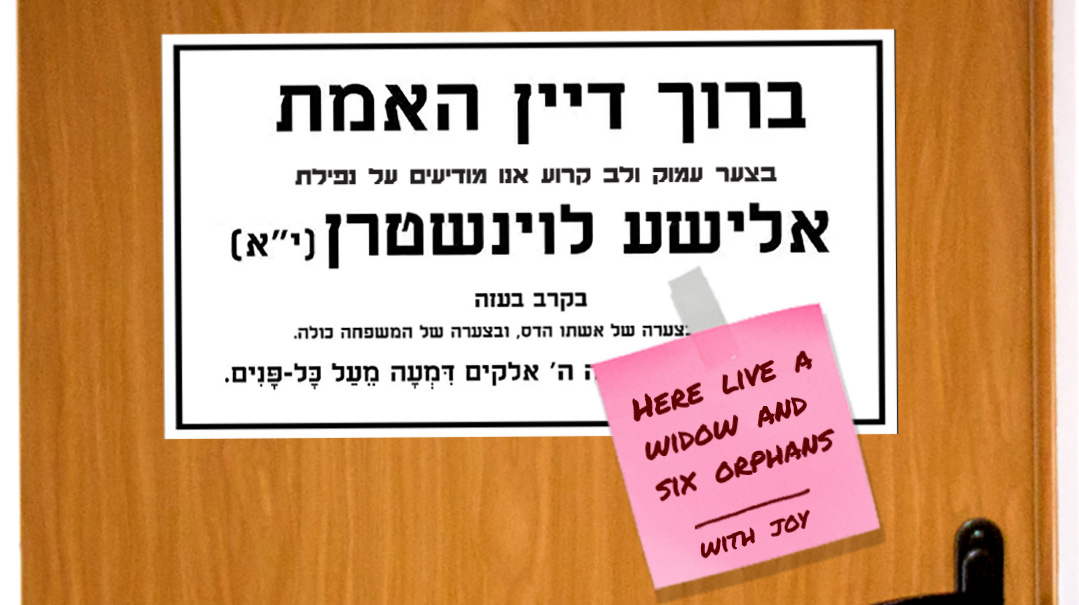

The second was a picture of a front door. On it was stuck the traditional mourning notice: Elisha Loewenstern, beloved husband, father, son, teacher — killed in Gaza, fighting for his nation. But next to it was attached another notice, this one handwritten. It read:

Here live a widow and six orphans

With joy

The two pictures left me wounded. Bewildered. Astounded. First, the family portrait. Ten weeks into the war, ten weeks of pictures, of reading each morning, “Hutar l’pirsum — It is permissible to publicize…” the names, the faces of our soldiers: Elkana and Ofir and Barak and Yoav and Sergey and Ariel from Karnei Shomron and Zichron Yaakov and Tel Aviv and Elazar and Beit Shemesh and and and.

But after all of this, this deluge of tragedy, there was still something left to shock. There was still a moment when I looked at this beautiful picture and my heart contracted and then continued to beat despite itself, despite the decimation of a family, despite the smiles of these beautiful children. It was that moment when something inside cracked open — as if it hadn’t enough already — and a chasm of loss and grief and disbelief rent across each of our hearts.

But someone was standing at the mouth of the chasm and reaching out her hand so that we would not fall into its endless depths. Hadas Loewenstern. There she was, the regal woman so many of us have come to recognize these past few weeks, her eyes kind but burning with passion and intensity; standing tall, erect; intricate mitpachat framing her face like a crown. There she was, with her signs and her emunah and her huge, generous spirit that seemed to embrace all of us around the world, every kind of Jew, even as she was thrust into loss and grief, when her beloved husband of 13 years was killed in Gaza. Part of the crew of one of the first tanks to enter Southern Gaza, Elisha realized that his friends had been injured and tried to save them. As he did so, his tank was hit by enemy fire.

Three hours after she was informed of her husband’s death, Hadas told the army representative that yes, she wanted to talk to the press. She had a message to relay. A message of strength, of unity, of meaning, of faith.

Gently, I question her about this: “If you had a message to share three hours after your world fell apart, that means you always had a message.”

Hadas takes a sip of her tea, then agrees. She always had a message. But now, the world’s eyes were upon her. And she spoke. “Talking about his death is secondary. He only died once. He lived every day. He literally grabbed every second. And I am alive and my six kids are alive and this is our plan: We plan on living a wonderful life. We’ll live. We’ll live in Eretz Yisrael and be a happy Jewish family. And this is the true victory.”

Deep Roots

When I first heard Hadas talk to the media, I called my daughter over to watch. “Look at this woman,” I told her. “She must have been born into generations of emunah. This is what happens when emunah is flowing in your blood. In times of need, it’s there.”

I repeated this to Hadas. “Actually, I was born into a secular family.”

I was floored.

“But that doesn’t mean I don’t have generations of emunah in my blood. Don’t I come from Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov? Don’t you?”

Hadas was born in Raanana and was proudly Zionist and secular — so much so, that she thought religious Jews were parasites. In fact, her first contact with a religious Jew was during her six-year army service, where she worked in the special 8200 unit as a human resources officer. There she met a religious officer who was married with children. “I thought he had a life filled with problems.” No lights on Shabbos. No shaking hands with a female officer. No listening to certain types of music. Mentally, Hadas dismissed him as a relic from the old world — in dire need of an update so he could live as regular humans do. After all, life is hard enough without making more problems for oneself.

“The more I spoke to him, the more I realized that he was so full of values and morals. And not just any kind of values — the same values as me.” Kibbud horim, for example, was one of the highest on Hadas’s list. “He asked me why, where does it come from? What’s the source of that value? And of course, it was from the Torah.

“Slowly, I realized that everything that meant the most to me — living in Eretz Yisrael, kindness, compassion, family — all of it originated in Torah. That was a shock. The Torah is an old, old book for old, old people. But without it, I had no meaning in my life today, as a secular Jew in Israel.”

A truth seeker, Hadas slowly took steps toward religion. It wasn’t easy. In the world she grew up in, being religious was a betrayal. It was a very long process, and in particular, Hadas struggled with the rejection of those who professed to be pluralistic and tolerant. Philosophical, Hadas compares this to the resistance she experienced when she stopped eating white flour and sugar. “People tell you you’re crazy. But I’d been crazy in the past, so that wasn’t going to stop me.”

One of the gifts she took with her was her wonderful childhood and the love and appreciation she had grown up with. “For some, their return to Judaism is catalyzed by hollowness, unhappiness, and difficult experiences.” For Hadas, that wasn’t the case, and she credits her healthy, happy upbringing for laying the foundation of a healthy, trusting relationship with Hashem.

Hadas and Elisha made an unlikely shidduch: a straight-speaking, fiery Israeli and a gentle American whose integrity was his core. Her fiery nature and his calm balanced each other out and though their temperaments were very different, their idealism was identical.

With her army life behind her, Hadas threw herself into learning and soon began teaching and lecturing. When the unthinkable happened, she had 15 years — and two millennia — of faith running through her. Of course, there were questions along the way. But questions are a door to a deeper understanding.

Hadas was particularly close to Rav Chaim Drukman z”l, whose wife, Dr. Sara, passed away last week. One of his classic lessons was that of Hineini — Avraham’s response to Hashem’s call at the Akeidah. This Hineini encapsulates the response of every Jew in every situation. We are here, ready to follow You, wherever You may lead.

It’s a declaration Hadas has made every single moment since her husband’s passing.

Hineinu: the story of Elisha. The story of Hadas. And the story of the Jewish people.

Taste of the Future

Hadas tells of how, before their wedding, the families went for a tasting session at the caterer. Neither of them was too interested in the food —“We just wanted to get married, they could have served pizza for all we cared”— but they went along with the formality. There, Elisha wrote Hadas a note: “I, Elisha Halevi ben HaRav Tzvi Meir promise to love you always, in This World and the Next World.” He signed his name.

“I said to him: ‘How do you know? Things might change. Maybe you’ll find out that I’m not such a great wife. How can you promise?’

“He said, ‘I promise.’

“And he stood by his word.”

On October 7, as news of the massacre broke, Elisha prepared to leave his family and travel to the battlefield. He fought for ten weeks until his untimely death. Soldiers fighting in Gaza leave their phones behind, and he managed only two short phone calls to his family in that time. But Hadas held down the fort, strengthening her children as to the significance of the battle: good versus evil. The right — and privilege — of being a Jew, a Jew in the Holy Land. The sanctity and preciousness of life.

The night before Elisha was killed in Gaza, he had a conversation with the other officers in his tank: To write farewell letters, in case the worst was to happen, or not to write? Elisha told his friends that he had no need to write a letter — he had worked all his life to let people know how much he loved them.

Hadas points to a picture of her children, perched upon one of the shelves of the bookcases that line the room. “I have six living letters. And I know exactly what he would want me to do and how he would want me to live. He was an ish yashar, an ish emet, a gentle man, who filled every moment with kindness.”

Hadas thinks for a minute and gives a wry smile. “At the moment, he’d probably also tell me not to work too hard.”

If I Were a Rich Man

“Why did it happen? I don’t know. I don’t care. Why go into G-d’s plan? I can’t change it.” A synthesis of faith and Israeli pragmatism has shaped Hadas’s inner world: not to go back and ask questions, but to accept that just as right now she’s doing the best with the resources she’s been given — so it was in the past. “You know, English has a whole grammatical construct: would have, should have. I should have known this, done this, been this. It doesn’t exist in Hebrew.” She sings a line from Fiddler on the Roof: “If I were a rich man.” She looks at me with comic exasperation. “But you’re not a rich man. So get on with what you have to do now with what you have.”

Doing what you have to do now, for Hadas, encompasses both gratitude and grief.

Grief: “I cry all the time. I carry a box of tissues with me around the house. I fall apart. That’s okay. At the same time, I will live. Sometimes a day at a time. Sometimes a minute at a time. But if they take away my simchat chayim, they will have won.”

Grief hits each member of the family in different ways, and Hadas simply enters their space of sorrow and grieves along with them. A well-wisher gifted their seven-year-old daughter with a large teddy bear. She hugged him tight and declared that she would call him Elisha. Crying, she told the bear: “I love you and miss you so much.” Hadas turned to her daughter and said, “Can I hug him, too?” Together, they cried and hugged that teddy bear: “Such a natural, healthy reaction: Something bad happened and we’re all very sad. And we’re also proud. And also happy to be Jews. And have the zechut of living in Eretz Yisrael.

“It’s not easy,” Hadas reflects. “Like all grief, there’s questions and there’s anger.” While the grief is present, it is not the whole picture: There’s also a deep pride in their father, in everything he stood for, in the exceptional person that he was, and at being a Jew in Eretz Yisrael.

And there’s gratitude.

“Not everyone has a husband. Not everyone has a great husband. Not everyone has six great kids. So before complaining, I first want to say thank you for all that I have. There are people out there from the South who have lost their families, their homes, everything. I had 13 years with Elisha, and he was a tzaddik. I have six children. I have a home. And I have a lifetime of love from Elisha.”

A Tent of Unity

Am Yisrael’s newfound unity has been a comfort to Hadas — but no surprise. Elisha was a man who transcended stereotypes. He taught secular boys for their bar mitzvahs, and was the only religious man in his company. He was an oleh from America. The shivah saw every type of Jew from across the political divide and the religious spectrum. Hadas reflects in sorrow: “In Masechet Succah, it says that all of Israel is worthy of sitting together in one succah. So Hashem opened a succat aveilim, a mourner’s tent, and we all sat together there.”

Hadas has felt the outpouring of love from across the ocean, as well, from communities in the US and further. To these people she urges strength, for the battle against good and evil is playing out across the world, as anti-Semitism rears its ugly head. “There’s a time difference on our watches. But there are no time differences in our hearts. We feel you praying for us and having a good time with your kids for us and jogging for us. We feel it here and we will all be together when Mashiach comes, and I will give all of you such a huge hug. The hugest hug ever.”

It’s not easy. But here Hadas draws on the story of Rus and Naomi at that critical moment when Naomi tries to dissuade Rus from returning with her and becoming Jewish. “Naomi told Rus, we’re a complicated people. There’ll be protests against you in colleges and on the streets. There are so many rules. But Rus insisted.”

The pasuk continues: And she [Naomi] saw that she was determined [mitametzet] to go with her and she ceased to argue with her (Rus 1:18).

Hadas seizes upon the word mitametzet [determined]. “That’s what a Jew needs. To try. To keep going. One step at a time, and maybe not even that. But we keep trying. Mitametzet. That’s the hallmark of a Jew.”

I nod. As we try, I want to add, we have certain people who urge us on. Who are one or two or ten steps ahead of us. Who point out both the horizon and the scenery en route. Who remind us that we are treading the pathway of our history. Our story as a nation. And the individual story of heartache and sorrow, of gratitude and faith that is the stuff of our lives.

We have people like Hadas Loewenstern.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 880)

Oops! We could not locate your form.