Story for the Ages

Rabbi Yisroel Greenwald and Rabbi Yossi Kirsch retrace the makings of their classic The Purim Story

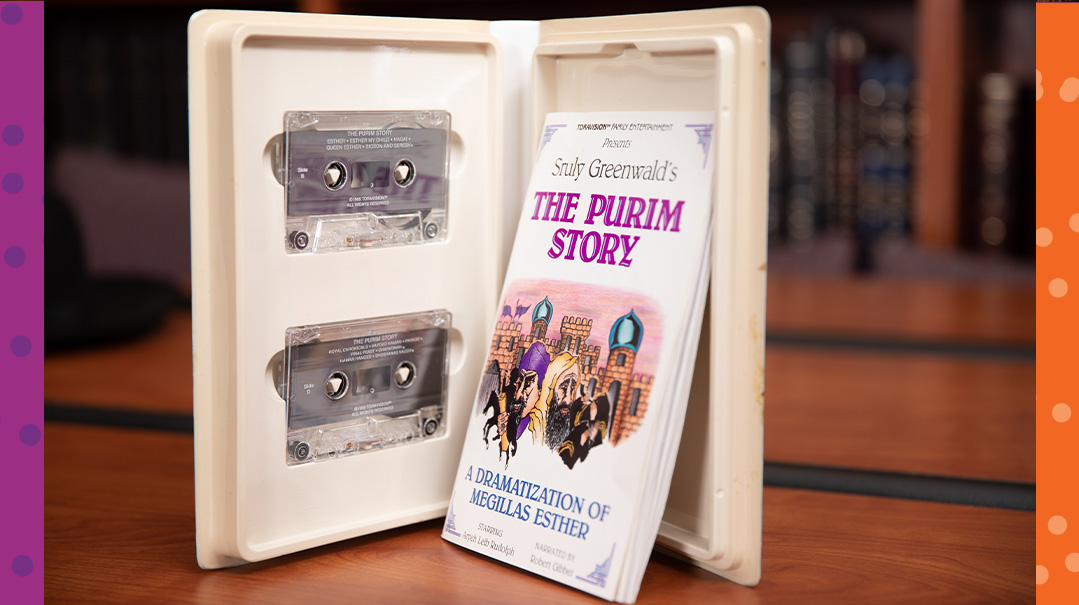

Photos: CK Studio

Okay, so here’s a pop halachah quiz:

If a fly falls into a cup of wine, what would you pasken? That’s right! You take out the fly and drink the wine. Now, if a Persian monarch touches the cup… Did you just say “spill it all out”? Amazing!

If your eyes are glazing over, that’s okay, you can turn the page, but if you’re already laughing and nodding along, you’re probably among the approximately 250,000 kids and parents who’ve listened to The Purim Story since its 1989 release. The enthusiasm for that iconic children’s story album hasn’t dwindled in 33 years, and for so many of us, those larger- than-life characters and adorable voices continue to lend so much color and graphic detail to our Purim experience.

Today, Rabbi Yisroel Greenwald and Rabbi Yossi Kirsch, masterminds behind the enduring tape, live at opposite ends of the world: Rabbi Greenwald is a dayan on the Melbourne, Australia beis din, and Rabbi Kirsch is chaplain at Menorah Park, a kosher senior center campus in Cleveland, Ohio. But on a recent trip to the US, Rabbi Greenwald got together with his old production buddy and I was invited along to reminisce.

Excited as I was to speak to the adult voices that had so formed my own childhood memories, there was an initial barrier I had to overcome. Those voices. When Rabbi Greenwald speaks, he is clearly Mordechai (“Goodbye Esther, goodbye Esther, and never forget, Hashem will always be, ah, with you”), and, when Rabbi Kirsch speaks, if you listen carefully, you can detect a trace of a familiar twang which, when manipulated correctly, makes an easy Achashveirosh (“Gentlemen, gentlemen, please, please, we have been dddebating this, hic, vital topic…”).

But, as I would soon learn, Rabbi Greenwald was also Seresh (“We’ll have to speak in the language of Tarshish… a cheeka binka binka bunka”), Shikur (“Not a pushka, a puska, now open up your mouth a little”), Shaul (“I’m 68… I just look so young because I exercise”), Shimshi (“I like fish too, especially fried fish with bread crumbs and lemon juice”), the Royal Chronicles Boy (“Tales of Vashti — no, that one’s too long”) and the voice of Royal Guard Number 1, putting in the “we’re here” of the timeless “We’re here… to do… the will of the King!”

And Rabbi Kirsch, who played Achashveirosh, must have assumed that evil enjoys company and, once you’re Achashveirosh, why not pile on Haman and Vashti as well? Then there’s Nutti (“Uh, Shaul, you always told me you’re 35”), the waiter (“Portuguese pigs, Scandinavian snails, rhinoceros bits, and elephant tails”) and a few other familiar characters.

But Purim is all about seeing beyond the surface, penetrating the veneer of simple, and revealing a story of depth and meaning. After 33 years, Rabbi Yossi Kirsch and Rabbi Yisroel Greenwald open up to share the story behind the story.

Fun Is Also Fine

Today, Rabbi Yisroel Greenwald lives in Melbourne, Australia where he serves as a dayan on the Melbourne beis din, is active in oversight of the Melbourne eiruv, and is a member of the Melbourne community kollel. He’s also a published author, whose books include Reb Mendel and His Wisdom — a biography on his lifetime mentor, Rav Mendel Kaplan, We Want Life! — a pictorial guide to the laws of lashon hara, What Are We Waiting For? Making the Geulah Come Alive, and two volumes of the A Festival of Torah series, based on the shiurim of Melbourne Rosh Kollel Rav Binyomim Wurzburger.

Though neither has pursued children’s tapes as a full-time career, The Purim Story was just the beginning. In the years since, they’ve worked together — along with Rabbi Benny Wielgus and a long list of others — on a number of different projects including Shimshon, A Chanukah Miracle, Professor Chai and The Torah Zoo (I and II), Match Made in Heaven, Tailor Made, and Blast Off. And Rabbi Greenwald has recently completed a script which, funds permitting, will one day make for a complex, state-of-the-art Yetzias Mitzrayim animation.

Their collaboration is far from coincidental. It is the result of a friendship that began almost as far back as they can remember. They were known as Sruly and Yossi back then, growing up in Brooklyn, where they attended Yeshiva Tiferes Torah in Boro Park for elementary school. It was in Kamenitz yeshivah high school, though, where each learned of the other’s passion for satirical drama.

In summer camp, their talent was put to test. During their high school years, they spent summers at Yeshivas HaKayitz, under the leadership of Rav Gershon Weiss. There, they collaborated in writing and performing a number of memorable skits and plays. Over the years, they attended other camps as well, and always, their performances would be met with uproarious laughter and thunderous applause.

But life wasn’t only about comedy. Following high school, the two friends headed off for the Philadelphia yeshivah where they met, for the first time, Rav Mendel Kaplan.

“When we came to Philly, Yossi and I became very attached to Reb Mendel,” says Rabbi Greenwald. “We cherished whatever he said or whatever experience we had with him. We would record it in a notebook after it happened.” This habit paid off. Later in life, when Rabbi Greenwald decided to write a biography about their beloved rebbi, a majority of its content came from these notebooks.

But aside from all the Torah and mussar they learned from Reb Mendel, they also picked up on a common theme, one that would mold their hashkafah forever: Torah should be sweet.

“Rebbi was once discussing the nusach of Bircas HaTorah,” Rabbi Greenwald remembers. “He pointed to the words V’Haarev Na — let it be sweet. ‘You see!’ he exclaimed, ‘the Gemara can actually be sweet in your mouth, or else why would Chazal have composed such a prayer?’”

This wasn’t just a lecture, it was how Rav Mendel lived, an idea he expressed often. “Once, Reb Mendel was teaching a Rashi in shiur. When he finished, he rubbed the tips of his fingers together and said, ‘Nu, do you hear the music of Rashi?’”

Music. Sweetness. All of it can be found in the Torah.

And it wasn’t only Reb Mendel who communicated this message. They also shared a relationship with Rav Avigdor Miller. “A highlight from our days in Kamenitz was packing into an old station wagon on Thursday nights and heading off to hear Rabbi Miller’s weekly Thursday night shmuess,” Rabbi Kirsch reminisces.

Rabbi Miller, with his unique personality, showed them how being funny and being serious needn’t be a contradiction. “We learned from Rabbi Miller how Torah and humor can complement each other,” they say. “Rabbi Miller could be so funny, he could have you in stitches, but his message was always serious, and so profound.”

From their great rebbeim they learned that Torah should be sweet, and that Torah and humor, when properly combined, can have incredible power.

But Rabbi Greenwald shares another thought as to why this concept carried such profundity on a personal level. “My parents were survivors,” he says. “Both were in the concentration camps. Most of my friends’ parents were survivors as well. For survivors, life was about surviving, and having fun just wasn’t a focus. Then, one day I was invited to a Shabbos meal by a friend whose parents were American-born. For the first time ever, I saw how fun can be part of chinuch too.”

True to the Story

Following their time in Philadelphia, Sruly and Yossi both headed off to Mir Brooklyn. It was during this time that Sruly decided to write a script that would give a humorous yet accurate portrayal of the Purim story. Writing the script, recording the vocals, and putting together the arrangements was a process that spanned several years, with stops and starts, long breaks and then spurts of frenzied activity.

The initial script was Sruly Greenwald’s project. “My tenth-grade English teacher once told me, ‘Sruly, you’d be able to conquer Hollywood, if you only knew how to spell.’” But for Rabbi Greenwald, it wasn’t only about talent — it was also a spiritual directive. “When you feel yourself gravitating toward a certain avodah,” he says, “it’s a sign that it’s your personalized mission.”

Properly executing his vision would take a lot more than talent — it would need some intensive learning. For months, fellow talmidim wondered why Sruly Greenwald was so engrossed in random midrashim relating to Purim. The script incorporates so many ma’amarei Chazal that when the album was finally released, they included a booklet of sources.

The booklet reveals so many nuances, the little quips and cute soundbites that all reflect authentic sources in Chazal. For example:

“At this party, everyone is served wine older than himself — how old are you, sir?” This is based on a Gemara in Megillah (12a) which states clearly that such was the practice at Achashveirosh’s party. (That someone might be tempted to claim his age to be 68 when it was, in fact, 35, was a slight oversight on Achashveirosh’s part).

Haman’s “There is a certain group in your empire” is worded in accordance with the Me’am Lo’ez, which says that Haman avoided mentioning the Jews explicitly since he suspected that Esther was a friend of the Jews and might intercede on their behalf. Haman therefore kept it vague, referring only to an anonymous, nonconformist group within Achashveirosh’s kingdom.

Following the “Hit it, Zeresh” cue, the song “When he’s declaring his G-d’s Oneness for all to see/You’ll tell the king he’s mocking our idolatry” comes from the midrash that explains how Haman’s friends advised him to approach Achashveirosh in the morning when Mordechai was saying Shema. Haman could point to this declaration of Divine unity as an illustration of Mordechai’s mocking Persian gods.

The emphasis on paraphrasing maamarei Chazal, explains Rabbi Greenwald, was not just for the sake of accuracy. The thorough review of Torah sources was a central part of the project’s objective. “We felt that people had a superficial understanding of the story, so we wanted to present the listeners with a rich tapestry of the events based on Chazal.”

And the humor is multileveled as well. While we of the younger generation giggled at the funny sounding voices of Shaul and Nutti, the older generation appreciated the throwback to the ‘60s-era cartoons many of them grew up with: the voices of Achashveirosh’s guards were spinoffs of three goofy royal guard dogs, Yippee, Yappee, and Yahooey; “Salami/Baloney” was a takeoff of a chant of homage in a vintage Popeye the Sailor installment in which, by eating his spinach, Popeye overpowers a village of African cannibals to become their king (the episode was subsequently banned for being racist). During the feast, as Achashveirosh and his cronies engage in a heated, drunken debate, we kids laughed at the ridiculous sounding argument, most of us failing to recognize the impersonations of Presidents Nixon, Carter, and Reagan, with “Hail to the Chief” playing in the background. And the gravelly voice of Charvonah was based on famous vaudevillian entertainer, Jimmy (The Great Schnozzola) Durante.

Yet with all their fun and veiled references, they never deviated from the actual story as told by Chazal. “We called the tape The Purim Story,” Rabbi Greenwald asserts, “because that’s what it is. It is the story of Purim, nothing more, nothing less.”

Rabbi Kirsch adds an uncanny story about how the album was broken down by a non-Jewish engineer, inadvertently reflecting Chazal’s intention. “The Gemara in Megillah (19a) brings four different opinions as to how much of the Megillah one must read to fulfill his obligation,” he explains. “Rabi Meir says you must read from the very beginning, where we learn about Achashveirosh’s feast. Rabi Yehudah says from ‘Ish Yehudi,’ where we are introduced to Mordechai. Rabi Yosi says from ‘Achar Hadevarim Ha’eileh’” where we’re introduced to Haman, and Rabi Shimon Bar Yochai concludes that one must read from “Balailah Hahu,” where Achashveirosh had trouble sleeping.

“Once we finally finished recording, I left the finished product with our studio engineer, a fellow named Steve Yates. I told him that we wanted it to be on two cassettes, which meant breaking it down into four sides, two sides for each cassette. I left the studio and let him do his thing. When I returned the next morning, I saw that he had broken it down as follows: Side A of the first tape begins with the story of Achashveirosh’s party, Side B begins with the narrator introducing “A Jewish man in Shushan,” Side A of the second tape begins with the rap “Here comes Haman, here comes Haman…” and Side B of the second tape begins with Achashveirosh counting sheep, trying to fall asleep. Steve Yates, the non-Jewish engineer, unwittingly divided the tape precisely in accordance with the four opinions cited in the Gemara.”

The script was written over the course of nine months but was then set aside for a number of years. During this time, the two friends moved on. Yossi married and moved to Chicago, where he became the first-grade rebbi in Yeshivas Tiferes Tzvi. Sruly went on to learn in Lakewood’s Beis Medrash Govoha, and, later, in Ohr Somayach of Monsey where he learned and taught on the side. It was during this time that The Purim Story resurfaced

Sitting together with the voices that formed my childhood memories was a thrill. Rabbi Kirsch and Rabbi Greenwald (R), for their part, never imagined their Purim creation, invested as it was, would endure three decades later

Team Spirit

Rabbi Yossi Kirsch doesn’t play music professionally but music has been a central part of his life since early childhood. “My father a”h loved Cantor David Werdyger and we played his records all the time. We knew Cantor Werdyger from Boro Park, and I remember being in the barber shop with him when I was a kid, and being amazed at the long Gerrer peyos he kept tucked in under his yarmulke.” His relationship with the Werdygers, he says, and Cantor Werdyger’s son Mendy in particular, would prove fruitful one day. The Werdyger family, with Mendy at the helm, went on to establish Aderet and Mostly Music. When the time came to distribute The Purim Story, they were a critical resource.

Over time, Yossi developed an ear for studio recordings in particular. In the 1980s, pop television icon Leonard Nimoy, who grew up in a traditional Jewish home, gave his star power to a production made by author Rabbi Chaim Clorfene and Lubavitcher physician and teacher Dr. Simcha Gottleib, called The Golem of Prague. The quality of the production, with its stunning sound effects and music, was an eye-opener to the level of professionalism that could be achieved with an audio recording.

“That was our goal,” says Rabbi Kirsch, “to emulate that high-quality production. I called Simcha Gottlieb and he gave freely of his time to share knowledge of how our Purim tape could be done.”

Rabbi Kirsch reached out to Rabbi Aharon Levitansky, who was then rosh yeshivah of Migdal Torah in Chicago, for help in finding someone who could play the part of Esther. Rabbi Kirsch’s wife’s family was close friends with the Levitanskys for years, and that seemed like the natural first stop for direction. Rabbi Levitansky recommended his student, Mrs. Karen Robbins. She came down to the studio and they knew they’d found their queen. But not only. When it came time to finding someone to do Haman’s wife, Zeresh, Mrs. Robbins said, “Well, I can do an evil Russian accent, too.”

Yossi Kirsch then went on to assemble the rest of the team. The first thing he needed was a narrator, and he had a candidate in mind, though he highly doubted the offer would be accepted. “Robert Gibber was the executive director of Yeshiva Tiferes Tzvi and he was an outstanding and gifted emcee for multiple klal projects at the time,” says Rabbi Kirsch. The challenge was that Robert Gibber generally lent his voice to serious projects — and The Purim Story didn’t quite fit the genre. But the zechus of their former rebbi, Rav Mendel Kaplan, stood them in good stead.

“Sruly and I approached him in his office, asking him to participate in the tape,” says Rabbi Kirsch. “All three of us shared a great love for our rebbi, Rav Mendel Kaplan ztz”l, and Robert relayed some heartwarming stories about his interaction with Reb Mendel when he was a high school bochur in Philadelphia.”

To their delight, Gibber accepted the job. Rabbi Kirsch explains that, from his perspective, Gibber’s narrating role was crucial in the tape’s overall success. “I’ve always felt that his sincere narration gave the tape a level of legitimacy and professionalism. His earnest narration is a good contrast to the humor and shenanigans that transpire during the scenes of the tape.”

There is one point, though, where Gibber’s narration takes on a humorous note. After Haman’s daughter realizes that it was her father whom she had publicly disgraced, she leaps from the window. There, Gibber says “You okay?”

“We’ll always be indebted to Robert for agreeing to do his exceptional narration,” Rabbi Kirsch says, “but we’re especially grateful for that one spot where he allowed his seriousness and humor to meet.”

A voice that would play several important parts is that of Aryeh Leib (Lew) Rudolph. At the time, the Rudolphs lived in Chicago and hosted a Shabbos Pirchei group led by Rabbi Kirsch. Kirsch and Rudolph became friends, and when it came time to record The Purim Story, Rudolph was happy to contribute. He played the voices of Mr. Akum (“Pipe down, Junior” — and Lew’s son Tzvi played Junior), Bigson (“So I take the poisonous snake and I put it in the king’s water, right?”) as well as several others. But one of his greatest contributions was the “Haman rap,” which wasn’t even part of the script. He just ad-libbed it on the spot. (Quick sidenote: I understand Lew Rudolph now lives in Eretz Yisrael. But if he’s reading this, I want him to know that I will never be able to hear the word “backstroke” without envisioning a big dopey guy in his pajamas standing sheepishly over a barrel of water trying to explain to a powerful king what a poisonous snake is doing there.)

“You can’t have a Purim story without some krias megillah,” Reb Yossi quips. “Leibel Trainer, son of the photographer, Harry Trainer, was the second-grade rebbi at Tiferes Tzvi, and we had him do the opening line of ‘Vayehi Bimei Achashveirosh,’ and later, ‘Vayavo Haman.’”

Rabbi Kirsch composed the unforgettable songs “Esther, My Child” and “We Can Do Teshuvah,” but who would sing them? Rudolph mentioned that he had cousins, Kenny and Yossi Finn, who were talented singers. They came down to the studio, recorded “Esther, My Child,” and also sang “Yom Zeh Mechubad” to show how the Jews of Persia kept Shabbos during Achashveirosh’s feast.

Reb Yossi also tapped the Atlas brothers — Shimmy, Akiva, and Binyanim — today well-known singers and musicians in the Chicago Jewish community, for assistance with the project. Their mother, Mrs. Eileen Atlas, wrote much of the music for the tape, and her sons sang “We Can Do Teshuvah” and joined the group singing “Shoshanas Yaakov’’ at the tape’s closing. Shimmy remembers how, while he and Akiva were singing the finale, one of the other singers started singing in a deliberately funny voice, and Shimmy and Akiva, hard as they tried, could not stop themselves from bursting into laughter. After a few tries, the crew decided to listen to how it sounded. It turned out that all the laughter actually lent an authentically happy feel to the song and so they decided to keep it.

The Atlases were also the ones who connected Rabbi Kirsch with Steve Yates, the studio engineer.

The actual voices took just two days to record. “But when I listened to them,” Rabbi Kirsch admits, “they sounded so… empty.” Adding the music and the sound effects was an eight-month process, with Rabbi Kirsch working together with Steve Yates.

But eight months of studio work is arduous, as well as costly. “My father lent me the money,” says Rabbi Greenwald. “At first, I was concerned about how I would pay it back. Baruch Hashem, the tape sold well and, in short order, the loan was paid in full.”

Reaching Hearts

When it was finally over, there was an understandable torrent of emotions — relief, happiness, hope. But, most of all, there was gratitude. Gratitude to Hashem and gratitude to the many who willingly gave of their time. “People were so gracious,” Rabbi Kirsch reflects. “So many people gave us chizuk, advice, and direction. So many stepped up to the plate giving what they had to offer, without asking for anything in return.”

There’s a uniquely eternal aspect about Purim — “Teshuasam hayisa lanetzach — the salvation of Purim shall be forever.” Purim encapsulates that internal essence of the Jewish soul that ensures the everlasting continuity of our People. Maybe that’s why kids (and adults) can still listen to The Purim Story and laugh at the jokes they know off by heart, even though they’ve already been playing it for years.

As for Rabbi Yisroel Greenwald and Rabbi Yossi Kirsch, they never imagined that a long-ago Purim project would still endure way into their own middle age. But maybe the unforeseen success is related to something they were told by the famous mashpia, Rav Don Segal, who knew Reb Sruli and Reb Yossi from the time he was a mashgiach in Mir. When they sent him The Purim Story, he commented that it is “a heilige tape.”

“Rav Don wasn’t referring to our shenanigans,” says Reb Yossi. “Rav Don is all about inspiration. I think he was referring to the fact that the tape succeeded in reaching the hearts of Jewish children. For Rav Don, this made it worthy of the title ‘heilige.’”

Shooting for the Stars

Over the years, Rabbi Greenwald got to know Steven Hill, the famous actor-turned-baal teshuvah, when the two would meet in the Satmar beis medrash in Monsey. When it came time to choose an actor to play the part of Haman, Rabbi Greenwald asked Hill if he would take the job. He turned it down, though, because he didn’t feel that the character was his style. Hill did entertain playing Mordechai, but ultimately declined. He explained that, when he acts, he invests his entire heart and soul into his performance. At the time, he didn’t feel he had what it took to put in that kind of time and energy.

Rabbis Kirsch and Greenwald seem to have a thing for world renowned Jewish actors. Rabbi Kirsch tells of a time where he pulled over at a rest stop on the Palisades Parkway. A few minutes later, another car pulled up and three men emerged. He recognized the one in the middle to be none other than Milton Berle, one of the most famous actors and entertainers at the time. Taken by surprise, Rabbi Kirsch blurted out, “Shalom Aleichem!” And Berle, whose real name was Mendel Berlinger, responded “Aleichem Shalom!” Berle then turned to one of the men accompanying him and said, “When a Yid says ‘Shalom Aleichem,’ you respond by saying ‘Aleichem Shalom.’”

Rap to the Future

Perhaps one of the most memorable parts of The Purim Story is the unplanned, ad-libbed “Haman Rap.” Originally, it was supposed to be a simple “Here comes Haman, here comes Haman” announcement, but as Lew Rudolph was saying it, he realized how rap-like it sounded and thus, the “Haman Rap” was created. Fast forward many years. Lew Rudolph and his wife, Mindy, are now living in Eretz Yisrael. Lew had lost his mother, and was davening from the amud, when a fellow who was in shul approached him and said, “You sound awfully familiar.”

“I’m not sure why,” Lew responded, “I don’t think I know you from anywhere.”

“Do you sing on any tapes?” the fellow asked.

“The only thing I ever did was The Purim Story,” Lew said.

The fellow couldn’t believe it. He turned to his son and said, “This is the guy!” He started listing off all the voices that Rudolph played, and then, he made Lew do the “Haman Rap,” right there in shul, even taking a selfie of himself, together with his childhood hero, singing the “Haman Rap” together.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 902)

Oops! We could not locate your form.