Stalin’s Poison Pill

Was Stalin's move to crush the Jews simply a violent spasm of anti-Semitism, or the far-reaching endgame of a cunning mind?

S omewhere in the vast kingdom of sadness that was Stalin’s gulag, Purim night of 1953 arrived and found a group of Jewish prisoners gathered around to hear the Megillah. At their head, prison garb obscuring his rabbinic pedigree, sat an inmate, later famous as the “Rabbi of the Russians” — Rav Yitzchak Zilber, who risked all to teach Torah in defiance of Soviet oppression.

As the story of salvation in ancient Persia was retold, an embittered prisoner called Isaac Mironovich found the mockery of a Purim too much to bear.

“Who needs your maasehs about what happened 2,500 years ago?” he burst out, almost lunging at the Megillah reader. “Tell me, where is your G-d today? Do you know what is about to happen to the Jews of the USSR? The Germans finished off six million — here they’re about to be done with another three!”

A shocked silence fell on the group as Mironovich’s words hit home. It was the height of the so-called “Doctors’ Plot.” Russia’s top medical experts — the majority of them Jewish — had recently been accused of attempting to kill the Kremlin leadership in the service of American and British intelligence. The impending show trial of the doctors was expected to be followed by the deportation of vast numbers of Jews who would disappear into the ravening maw of the Soviet labor camp system.

Even in this isolated prison, rumors of that fate were rife: the personnel departments said to be hard at work assembling lists of Jews; the hundreds of trains gathering outside Moscow and other big cities to deport them to the east; the gigantic, unheated barracks that were being readied to house them in sub-zero temperatures.

All of that hung in the air as Mironovich finished his outburst. But Rav Zilber quietly responded with words of hope. “True, our situation is difficult,” he said, “but Haman also sent orders for our destruction. The great Stalin is no more than a mere mortal — no one can tell what will happen to him in half an hour!”

On Purim morning, it became clear just how prophetic those words had been. Isaac Mironovich came looking for Rav Zilber, and told him excitedly: “Yitzchak, do you remember what happened yesterday? At seven-fifty p.m. you said that Stalin is no more than flesh and blood. Today, someone whispered to me that he heard on German radio that last night at eight twenty-three p.m., Stalin suffered a stroke!”

The stunning report was true. Four days after that conversation, having endured an agonizingly drawn-out end, Stalin was dead, and with him died the Doctors’ Plot.

Seven decades after the sword was lifted from the neck of Russian Jewry, archives that were opened after Communism’s fall reveal much of what was obscured from observers like the CIA, who struggled to decipher the meaning of the Soviet blood libel in real time.

We can discern the outlines of the vicious intrigue that accompanied the Plot, as rival Kremlin bosses jockeyed for influence and saw a campaign against the Jews as a way to destroy their foes.

We can track Stalin’s early moves as, like some grotesque, giant spider, he spins a web from 1948 onwards, that would ensnare millions of Soviet Jews when the details of the alleged plot were splashed across the pages of Pravda in January 1953.

But despite the wealth of archival evidence, many questions will likely remain unanswerable — first and foremost, Stalin’s motivation. Was this simply the spasm of anti-Semitism that dictatorial regimes are wont to indulge in; latent Jew-hatred that had been disguised by high-flown talk of a communist utopia? Or, as some researchers have argued, did the Soviet leader use anti-Semitism more strategically, as a tool to signal a new campaign to purge any backsliders in the Socialist Eden?

No number of official documents can capture the terror of Soviet Jews, as newspaper headlines screamed about Zionist perfidy, non-Jewish acquaintances cold-shouldered them in the street, and taunted them about their impending doom. For these, it’s left to “history with its flickering lamp,” as Winston Churchill said, to shed its feeble light on the trail of those terrible times.

The Jewish pride displayed by the thousands who greeted Golda Meir (circled) on Rosh Hashanah alarmed Stalin

A Jewish Daughter

The scenes of joy in central Moscow on Rosh Hashanah 1948 were hallucinatory. After decades of Stalin’s iron rule, Soviet citizens knew better than to demonstrate enthusiasm for anything other than good Socialist causes, yet outside the Choral Synagogue, thousands of Moscow’s Jews erupted in a spontaneous show of Jewish pride.

The trigger was the visit of the newly-declared State of Israel’s first ambassador to Moscow — future prime minister Golda Meir. The posting was a very sensitive one. Due to Stalin’s hope that socialist Israel would move into the USSR’s orbit, he’d cast a crucial vote at the United Nations Security Council in favor of Israel’s creation just five months before. The Soviet leader had actively assisted Israel’s first battles, allowing the transfer of Czech arms such as fighter planes to the new state, which featured prominently in the War of Independence.

On the other hand, the Soviets were no Zionists; they viewed non-Russian nationalism as inherently dangerous. In the months before Meir’s arrival, a campaign targeting Jewish intellectuals had gotten underway. The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC), a state-backed body of leading Soviet Jews which acted as a propaganda mouthpiece to the West, had come under attack for being too “cosmopolitan” and pro-Western.

The chairman of the Committee was Solomon Mikhoels, Russia’s leading exponent of Shakespearean drama and director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater. Despite leading a wartime tour of America and England that netted millions of dollars in aid to the Soviet war effort, Mikhoels fell foul of Stalin’s suspicious mind, due to those very international contacts.

So, in January 1948, he was murdered by secret police in Minsk, in what was made to look like a car accident. Then, the other members of the Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested.

When Meir arrived to take up her posting in early September, the anti-Jewish crackdown had intensified in response to an article by celebrated Soviet-Jewish writer Ilya Ehrenburg that had spoken positively of Israel — a position that increased Stalin’s suspicions of Israeli influence.

Wanting to open a bridge to the millions of Russian Jews cut off behind the Iron Curtain since the 1920s, says Yaakov Livneh, an Israeli diplomat, Meir headed to shul on Rosh Hashanah. The sight there astounded her, as she later told the Israeli government.

Stalin with spy chief Lavrentiy Beria

“The street in front of the synagogue was full of people, packed like sardines, with hundreds of people of all ages, including officers of the Red Army, teenagers, and babies in the arms of their parents. Usually, about 2,000 Jews came to the synagogue on Rosh Hashanah, but now a crowd of nearly 50,000 people awaited us.”

Cries of “Shalom” and “Nasha Golda” — Our Golda — echoed in the streets, just minutes away from the Kremlin. Once inside, the ambassador testified, women came up to her and wordlessly saluted her, caressing and kissing her dress. On the walls were signs declaring, “Am Yisrael Chai.”

“My grandfather, who was present in the audience, told how Golda passed by him,” says Yaakov Livneh. “He told her, ‘l’Shanah Haba’ah Bi’Yerushalayim,’ but full of tears, she didn’t reply.”

The scenes, repeated on Yom Kippur, were immortalized in a famous picture which adorned an Israeli banknote alongside the words, “Sh’lach Et Ami,” or “Let My People Go” — testament to the resonance of the event in the long struggle for Soviet Jewry.

But the outpouring of Jewish identity on display outside the shul on Rosh Hashanah, within hailing distance of the nerve center of Soviet power, would bode ill for the USSR’s Jews.

“Stalin saw something dangerous to his regime, in the sudden appearance of a bond among Jews that was incomprehensible to him,” says Jonathan Brent, author of Stalin’s Last Crime, an authoritative history of the Doctors’ Plot.

Currently the director of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Brent spent two decades as editorial director of Yale University Press, where he established the Annals of Communism series. Throughout the 1990s he had extensive access to the major Soviet archives in Moscow, publishing his work on the Doctors’ Plot in collaboration with Vladimir Naumov, a history professor who had been part of the team that led President Gorbachev’s glasnost.

The archival access yielded a paper trail that led to Brent’s central thesis about Stalin’s last, sinister power-play: that the Plot was no mere anti-Semitic outburst, but a calculated, long-planned move to tighten his personal grip on power in a world where he perceived the democracies to pose a major threat to the USSR.

“Ahead of the confrontation with America that he believed was coming, Stalin’s ultimate purpose was to initiate a return to the purges that had preceded the war with Germany. Krushchev later blamed the Doctors’ Plot on plain anti-Semitism, but while Stalin was an anti-Semite, there was something far more calculated here: he believed that the only way to secure the Soviet Union was to eliminate all American influence — starting with the Jews.”

Stalin was increasingly suspicious of Jews, many of whom — including the wives of some of the Soviet leadership — had relatives in America or Israel.

Ilya Ehrenburg himself knew that Stalin was watching anyone who came into contact with the Israeli diplomats, who were under tight surveillance. Even when he met Golda Meir at a reception, he appeared to be drunk and argued with her over her inability to speak Russian.

But one woman got carried away. Polina Zhemchuzhina was the wife of Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, and a high-ranking Soviet official in her own right. Born Perl Karpovskaya to the family of a Jewish tailor in what’s now Ukraine, Zhemchuzhina (Russian for “pearl,” a nod to her Yiddish name) remained an ardent Stalinist to the end of her life.

With one brother in Israel and another in the United States, she was a suspect personality. So, increasingly, was her powerful husband. When Stalin went to recuperate from illness in Sochi on the Black Sea in the late 1940s, Foreign Minister Molotov made one mistake too many.

He let it be known to foreign correspondents that he was pleased with the warming post-war ties with the West, and was an advocate for the easing of the USSR’s strict censorship. The reports drew furious condemnation from Stalin, making Molotov’s position increasingly tenuous.

And then Rosh Hashanah gave Stalin the excuse to strike. Molotov’s wife — a deeply assimilated Jew whose parents had sat shivah when she married out — was tasked with guiding Golda Meir on her visit. The hardened Communist was so moved by her encounter, that she reached deep into her past, emotionally declaring to her guest, “Ich bin ein Yiddishe tochter — I’m a Jewish daughter.”

When the astounding incident got back to Stalin, says Jonathan Brent, it became one more factor that led the Communist overlord to his decision: the Jews of the Soviet Union weren’t to be trusted —and they had to go.

The official propaganda campaign against the doctors had a nakedly anti—Semitic, Der Sturmer-like quality

The First Death

Like the nuclear technology that the USSR was then stealing from America, the creation of the Doctors’ Plot was a chain reaction: arrest led to arrest, one tortured confession led to another, until Stalin had what he wanted.

It was a chain that was only linked retrospectively. When Comrade Andrei Aleksandrovich Zhdanov died of heart failure in August 1948, he was officially mourned as befit a senior Politburo member who had once been on course to succeed Stalin. He was buried near Lenin in Red Square, and with typical Soviet megalomania, his birthplace — Mariupol, in Ukraine — was renamed in his honor.

Zhdanov may have believed heart-and-soul in Communism, but his cardiac health was weak, so when, the day before Zhdanov died the Kremlin security chief received a letter from a mid-ranking Kremlin doctor, Lydia Timashuk, accusing her superiors of medical malpractice in the case by missing obvious signs of a heart attack, the security chief did nothing.

So did Viktor Abakumov, head of the MSB (the KGB’s previous incarnation) who merely forwarded it to Stalin. The leader himself did nothing beyond signing it with the words, “Into the archive.”

But from this insignificant genesis — the death of a Communist bigwig that involved no Jewish doctors — metastasized the accusations of a vast Jewish medical conspiracy to target the Soviet leadership. In retrospect, the unfolding drama provides a window into the terrible, Darwinian war of survival waged among the Kremlin elites that was Stalin’s method of governance.

In the decade before, NKVD boss Genrikh Yagoda had been arrested and shot, to be replaced by Nikolai Yezhov — known as the “Bloody Dwarf” —who was likewise killed when he’d outlived his usefulness.

The missing link in the chain that eventually connected Zhdanov to the Doctors’ Plot was the brutal personality of Viktor Abakumov’s deputy, a vicious anti-Semite called Mikhail Ryumin. Described by Stalin as a “pygmy,” over the course of an 18-month rampage, he climbed further up the greasy pole of Soviet power by dethroning his boss, torturing Jewish doctors into admitting their part in the plot, and purging the MSB of Jews.

His reign of terror began with the 1950 arrest of Dr Yakov Etinger, a leading cardiologist. Widely traveled and with foreign contacts, Etinger was precisely the type of rootless cosmopolitan that Soviet propaganda warned about, so the security services bugged his house. The device indeed yielded a rich harvest: private conversations with his wife and adopted son that were highly critical of the USSR’s leadership.

In an example of the pedestrian details that could incriminate a man in Soviet Russia, he was reported to read the Jewish Chronicle, a “bourgeois, Anglo-Jewish magazine” that is still on newsstands in Britain today.

Etinger disappeared into Moscow’s notorious Lefortovo Prison, from where he never emerged. Under prolonged interrogation by Viktor Abakumov, the MSB head, Etinger admitted to Jewish nationalism, but there was no evidence that he had conspired to kill Soviet leaders, even though he had treated two, who both died of heart failure.

With the prolonged interrogation taking a toll on Etinger’s own heart, Abakumov stopped the interrogation for lack of evidence. It was, very literally, a fatal mistake for the MSB boss himself.

Ambitious to supplant his boss, Abakumov’s deputy, Mikhail Ryumin spied his chance. He continued the interrogation of Dr Etinger in secret, with unbelievable brutality. Over the course of two months, the elderly doctor was interrogated for hours each day, forced to stand all the time, and deprived of sleep.

The end was predictable: at the beginning of March 1951, the cardiac specialist who had been accused of overseeing his patient’s deaths, died of a heart attack himself after returning to his cell from interrogation.

Ryumin knew what he had to do: on July 2, 1951, he composed a letter to Stalin, embellishing Etinger’s confession to include an admission of murdering Aleksandr Shcherbakov, a Soviet leader who had died in 1945 under Etinger’s care, and adding that Viktor Abakumov had tried to cover up Etinger’s confession.

Finally, Stalin had what he wanted: a man who could deliver the evidence that a leading Jewish doctor, in the service of the USSR’s enemies, had killed senior Soviet figures, and that the top ranks of the security services were complicit.

This linear account obscures the difficulty of discerning the sequence of events, which only became possible through archival evidence of what went on in the closed upper spheres of the Soviet world.

In historical terms, says Jonathan Brent, the smoking gun is the so-called “secret letter” — a July 13, 1951, communication from the Communist Party’s Central Committee, which had met at Stalin’s request in the wake of Ryumin’s “revelations.”

The letter, which was disseminated to officials across the length and breadth of the USSR, was the first official allegation that Dr Etinger’s standalone case was a sign of something far worse: the existence of a “conspiratorial group” among Kremlin doctors who planned to murder Soviet leaders.

Among Soviet officialdom, the letter acted as a signal that was termed the “anti-cosmopolitan” —read: Jewish — campaign was moving into high gear.

Over the next year, Mikhail Ryumin — the brutal “pygmy” who was for the meantime a firm favorite of Stalin’s — would extract one forced confession after another from Jewish doctors and Kremlin officials, until he could establish an incriminating trail leading back to the death of Zhdanov in 1948.

Abakumov was arrested, Ryumin was promoted, and the Doctors’ Plot was afoot.

Described by Stalin as a “pygmy”, Mikhail Ryumin (left) climbed up the MSB’s greasy pole by denouncing his boss Viktor Abakumov (right)

Sand in the Works

Across Eastern Europe over the next year, the campaign against the Jews gathered steam and became a pan-Soviet struggle as Stalin readied the USSR and the world for his dramatic revelation of Jewish perfidy. In August 1952, 13 Soviet Jewish poets and writers, five of them members of the Anti-Fascist Committee, were executed in the Lubyanka Prison in Moscow.

Then in November came the most openly anti-Semitic display to date: the show trial of Czech Communist leader Rudolf Slansky.

It was a Jewish tragedy that the Communist vanguard everywhere — the atheistic, anti-religious movement’s most enthusiastic early adopters — were themselves often Jewish. Countless Jewish parents had wept as their children were swept up with socialist fervor — often turning on their own brethren in their revolutionary zeal. Many of these true believers would die on the altar of High Stalinism.

Broadcast on state media, the trial of the Jewish Slansky and his co-conspirators — 11 of whom were Jewish — for being part of a Zionist conspiracy was accompanied by a campaign to oust Jews from prominent positions across Czechoslovakia.

At the end of the year, things had gone so far that Stalin told the Central Committee — the powerful executive body at the top of the Soviet pyramid — that “every Jew is a potential spy for the US.”

But despite all the sickening progress of his sham investigation, extracted by truncheon beatings on elderly physicians, Stalin’s case against the Jews was still progressing slowly. Why did he so painstakingly work to extract the confessions, not simply let Soviet propaganda do its deadly work in rallying the public against the Jews?

The answer, says Jonathan Brent, is that Stalin wasn’t Saddam Hussein, unleashing bloody terror at a whim. It was important to Stalin to preserve a thin veneer of legitimacy both within Russian and abroad, by working within the Soviet legal system.

All of that meant that as the clock ran down on Stalin’s life, the conspiracy against Russia’s Jews to which he’d dedicated his final years was still incomplete — and any delay was one step closer to Stalin’s death and the escape of the USSR’s Jews.

As 1952 drew to a close, the last stumbling block was the stubborn refusal of one brave Jewish doctor to submit to torture and confess to crimes that she hadn’t committed. Sophia Karpai had carried out an EKG on Andrei Zhdanov three weeks before his death, and for that crime, had been subjected to relentless torture in a bid to extract a confession that would link Jews to the crime of Zhdanov’s death.

At one point, she was the only Jewish doctor in prison — a fact that prolonged her life, as Stalin hoped that she would eventually incriminate others.

But where some of the MSB’s toughest, most sadistic interrogators were broken in the very torture chambers that they’d run, Karpai — held in a refrigerated cell to prevent her sleeping — didn’t submit. In an act of Hashgachah that would save Soviet Jewry, that heroic resistance combined with Stalin’s faux-legalism, acted as a rearguard action slowing down the inevitable.

“Like grains of sand in the gears of the huge machine that had been set in motion,” says Jonathan Brent, “the delays caused by Sophia Karpai’s heroism saved the lives of thousands, if not millions, of people.”

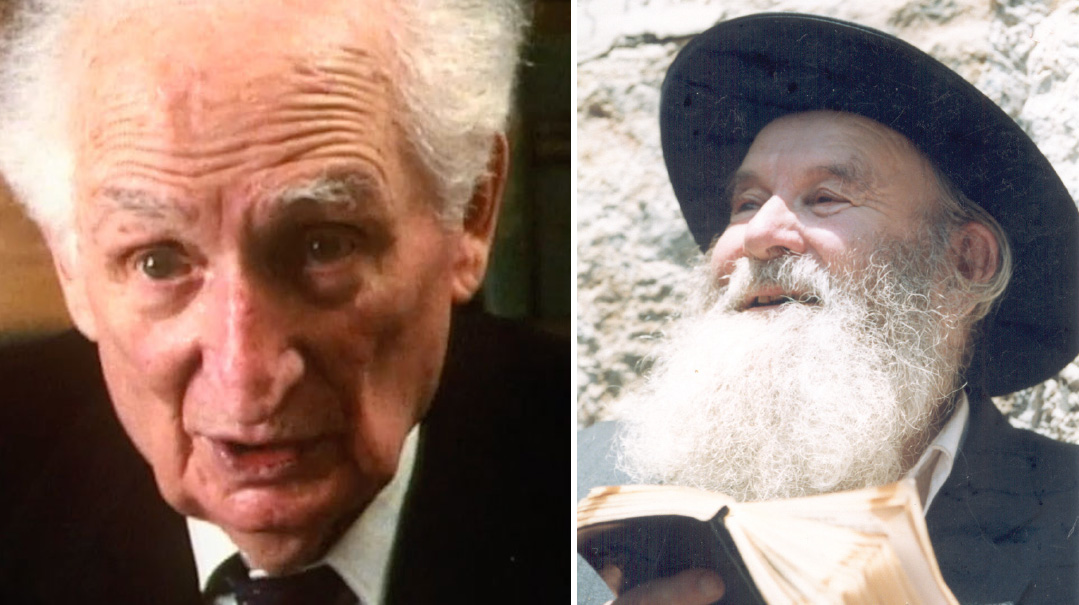

“Stalin is no more than a mortal” – The prophetic words of Rav Yitzchak Zilber (right), were experienced first-hand by Dr Yakov Rapoport (left) in the interrogation room

“Saboteur-doctors”

ON January 13, 1953, the long-threatened storm broke. Pravda, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, released a bombshell report that a group of “saboteur-doctors, a terrorist group uncovered some time ago by organs of state security,” had been arrested. The group, the report claimed, “had set itself the goal of shortening the lives of leaders of the Soviet Union by medical sabotage.”

Then in the lurid, violent rhetoric favored by Soviet writers, the report fingered the Jews as a group. “Most of the members of this terrorist group were bought by American intelligence. They were recruited by the international Jewish bourgeois-nationalist organization known as ‘Joint.’ The filthy face of this Zionist espionage organization hiding under the mask of charity has been exposed.

“The unmasking of the band of doctor-poisoners dealt a shattering blow to the American-English instigators of war. The whole world can now see the true face of the slave master-cannibals from the USA and England.”

As the names of the doctors — Kogan, Vovsi, Grinshtein, Feldman, Etinger — made clear, most of the accused were Jewish. Their targets beyond Zhdanov were said to include Soviet war heroes such as Field Marshals Vasilevsky and Govorov.

The effect of the allegations on Soviet Jews’ morale and standing was devastating. The anti-Semitic campaign acted as a giant dog-whistle that brought the country’s latent Jew-hatred out. Ordinary Russians stopped visiting Jewish doctors and pharmacists, scared of being poisoned. Meetings were held in factories where workers denounced the accused in anti-Semitic terms, and demanded the death penalty. There were rumors that the accused would be hanged on Red Square in giant spectacles.

Midnight Knock

In a country where speaking your mind could prove deadly — where even typewriters had to be registered — firsthand evidence of the terror that millions of people felt, is hard to come by. But it’s possible to gain a shadowy impression, in the form of memoirs of the plot years and wider Soviet life.

Natalya Rapaport had an insider’s view of the terror. When she was 14 years old, she opened the door to find the squad of MSB thugs who’d come to arrest her father, Yakov, a senior Soviet pathologist.

Natasha, as she was called, had grown up in the cocooned, privileged world of the Soviet Jewish intelligentsia. She attended Model School Number 29, an elite institution that furnished the children who appeared in front of Stalin on the annual May Day parade.

In her memoir, Stalin and Medicine, Natasha — a doctor like her father, who went on to emigrate to America where she specialized in drug research — recalls her childhood dream to be positioned next to Comrade Stalin on the reviewing stand at the parade. She was devastated that on the morning of the big day, her father claimed to have discovered that she had tonsillitis in a ploy to keep her at home.

Years later, she learned that her parents knew the fate of one iconic child pictured on Stalin’s lap, whose parents were subsequently killed.

But even as her parents’ friends disappeared one by one as the events of the Doctors’ Plot unfolded, the naïve teen remained unaware, until her own pediatrician — a gentle soul called Dr. Miron Vovsi — was arrested, and accused of being one of the “evildoers dressed in white gowns.”

It was a matter of time before her parents — both doctors — were targeted. And then, at the end of January, with the Doctors’ Plot two weeks old, it happened.

“That night I was alone at home when there was a loud knock on the door,” she told the BBC in 2019. “I opened it, and there was a crowd of men that I decided were burglars.”

The men were MSB agents, and they’d come for Professor Rapaport. Despite his being a pathologist, he was swept up in the drag net, accused of signing false death certificates to cover for his co-religionists who had killed the leaders.

When the phone rang, one of the agents grabbed the terrified girl and barked at her to answer it.

“It was my father on the phone, and I fainted. I was unconscious for hours, and didn’t see my parents being taken away when they came home.”

It took 24 hours before her mother was released, but when Natasha Rapaport once again stepped out of her front door to confront the world, it was to be shunned by friends as the child of a murderer. The mother and daughter were kept from starvation by a few brave people who fed them despite the threat of being rounded up themselves.

“On the radio, all we heard was talk of the ‘scum of the earth, Jewish doctors who sold their souls,’ Rapaport recalls. “There was a distinct scent of pogrom in the air. Rumors spread that all Soviet Jews would be relocated to Siberia, to special camps — all for their own protection, to shield them from the wrath of the public.”

Frozen Destruction

Like an airborne plague, the same terrible rumors circulated in the Soviet prison camp system, where Rav Yitzchak Zilber was an inmate that Purim. All over the camp hung posters of a bearded man with a crooked nose, dressed in a white coat, who was cutting a baby. The writing underneath proclaimed, “Killer Doctors.”

“When I would pass by such a poster,” Rav Yitzchak Zilber recalled, “I would inevitably hear from the bystanders, ‘Hey, Abrasha! (a Jewish nickname for Abraham), what are your doctors doing to our children?’ ”

What was the truth of those rumors about trains and deportations — were the shocking official denunciations indeed meant to be the prelude to the start of a Soviet Holocaust?

While some rumors were a byproduct of the fevered times, says Jonathan Brent, the archival evidence shows that the fears of Soviet Jews were well-founded: the Soviet state was indeed gearing up to inflict unimaginable horror on its Jewish citizens.

“We found documentation of the construction of four giant concentration camps — large enough for hundreds of thousands of people. Officially, the giant camps were intended for ‘especially dangerous criminals.’ But who were they?

“As a young man, Vladimir Naumov had a friend who worked on the construction of one of the camps and he was told that they were for the Jews. There’s no doubt that Stalin would have gone ahead with the deportation — and these frozen camps would have led to the deaths of thousands.”

Brent was able to find no proof of the report that has gained widespread currency since Stalin’s era of “Day X” — the date that Stalin was reported to have fixed for the mass deportation of Jews.

Similarly, the rumor of pamphlets providing a legal basis for the Jews’ expulsion that were said to have been printed and stored in an MGB vault have not been traced. Likewise, the assembly of hundreds of freight cars around Moscow in preparation for the mass deportation has also not been substantiated.

But a document’s absence, says Brent, doesn’t mean much in the Soviet context. “In a conspiratorial society that had no rule of law, every piece of paper was political and could be used as a weapon.”

One contemporary report that has been partly substantiated is that of an open letter to Stalin that was said to have been prepared by Jewish public figures urging the Soviet leader to deport Jews to protect them from displays of popular vengeance for their perfidy.

Support for that is found in a letter from Ilya Ehrenburg to Stalin, attached to the draft of an open letter from a long list of Jews arguing that the Jewish people was irreparably divided into two parts — the bosses, represented by the capitalistic State of Israel, and workers, who should find their sanctuary in the USSR.

Adding to the self-debasement in this letter — which was never published — Ehrenburg added his own letter to the dictator.

“You understand, dear Iosif Vissarionovich, that I myself cannot answer these questions, and therefore I dare to write to You. There is talk of an important political act, and I decided to request that you charge a leading government figure to inform me whether it’s desirable to have my signature on it.”

Three weeks after the eruption of the Doctors’ Plot, the “important political act” would seem to be the logical next stage that was being widely discussed — the deportation of the Jews.

Persecution Complex

With a deep gloom settled on the Soviet Jewish community, beyond the USSR’s borders, observers trying to decipher the Kremlin’s moves found themselves in a fog.

A declassified CIA paper from immediately after Stalin’s death gives some idea of the lack of clarity: With few human sources on the ground feeding information, the analysts were forced to speculate that “the 13 January Pravda article disclosing the doctors’ plot must have had a shattering effect on the citizens of the USSR.”

The writers attempted to read the Kremlin runes by noting oddities such as the fact that the doctors were accused of attempting to kill army generals and an admiral, but no air force commander. Similarly, it noted a shift in rhetoric between November and December 1952, when the accusations grew more specifically anti-Jewish — both facts that the authors were at a loss to explain.

Five days after the announcement of the doctors’ actions, the New York Times asked: “What does Moscow hope to gain by the purge? Because no correspondent is ever able to report what goes on behind the crenelated walls of the Kremlin, the West has no way of knowing the answers. The assumption is that the Kremlin’s insecurity has been intensified by the bitter rivalry within the hierarchy for Stalin’s succession.”

In parallel, American Jews were enduring their own Soviet-related saga, which took up a lot of their attention. The treason of Julius Rosenberg — who was executed together with his wife Ethel on June 19, 1953 — was deeply embarrassing for the Jewish community, who felt that they had to compensate, by espousing an ultra-patriotism.

“There’s a bitter irony, one that paralyzes the imagination, that at the same time as Rosenberg spied for the USSR, it was moving to destroy his own people,” says Jonathan Brent.

Let My People Go

Over in Israel, the Labor Party newspaper, Hador, compared the Soviet charges to the Beilis blood libel trial in Russia four decades before under the Czarist regime.

To Israeli officials, the lack of information was deeply worrying. It was Golda’s 1948 Rosh Hashanah visit that had arguably begun the long descent to the anti-Jewish violence.

With the denouement of the process, the Israeli government was faced with very few options: they couldn’t risk poking the angry Soviet bear, but how could they stand by as millions of Jews were threatened, less than a decade after the Holocaust?

Five days after the doctors were indicted, the Israeli cabinet debated the way forward, and a clash emerged between Welfare Minister Haim Moshe Shapira, of the Mizrachi Party — a consistent dove — and the hawkish Pinhas Lavon, a minister without portfolio.

Shapira questioned whether the case targeted Jews specifically. “Russia is probably facing a very broad cleansing and we have to be careful that if we emphasize the Jewish point too much, it could turn into a Jewish point.” He cautioned that the Soviet fulminations against the Joint showed that Stalin’s target was America, and that Israel shouldn’t be seen to be doing the US’s work.

Lavon disagreed, saying that in the trials, the State of Israel and Zionism were presented as the Elders of Zion, a nation of well-poisoners.

But ultimately, the government resolved to do whatever little was in its power as a minnow against the giant Soviet Union: to demand the release of Soviet Jews.

The slogan that was chosen echoed Moshe’s demand of Pharaoh: “Send My People” — or as it became in the later slogan of the Soviet Jewry movement — “Let My People Go.”

The Doctors’ Plot was a turning point in Israel’s relationship with the USSR. Up to that point, Israel — as Minister Shapira advocated — wouldn’t openly challenge the Soviets. But with this open demonstration of state-sponsored anti-Semitism, the die was cast: from Israel’s point of view, the Cold War was on.

Practically speaking, that meant an immediate campaign against Stalin’s fellow travelers in Israel’s Communist Party (known as MAKI). They were called the “Matzdikei Hadin” — those who justified the show trial of the Jews.

Ben Gurion fiercely detested the Communists but had never moved against them. Thus, the Stalinist Kol Ha’am newspaper parroted the official Soviet line, calling the Jewish doctors “a gang of murderer-doctors” in a way that provoked fury on the government benches.

Nothing came of the call to shut down the newspaper, but like all Stalinist organizations worldwide, their support would soon plunge, as Stalin’s crimes were exposed after his impending death.

As January gave way to February, reports showed that the pace of persecution was quickening. Leading scientists in medicine, nuclear physics, and electronics were gathered and harangued about the need for vigilance because of the “miserable band of doctor wreckers.”

Moscow radio also reported from Kiev that a number of Jewish doctors in Nikolaev, in Ukraine, were being charged with defrauding the state of more than 600,000 rubles. Again, the conspicuously Jewish-named doctors were listed: Cohen, Zaslavsky, Roitelman, Gendelman, Levin, Olshanetsky, Erlichman, Yasny, Wasserman, Ravitch, Heller, and Sheftel.

Major Jewish cultural luminaries, such as novelist Vassily Grossman, came under attack in a party newspaper for his new novel on Stalingrad, which had been praised earlier as a literary masterpiece, but as a result of Grossman’s roots, was now deemed suspect.

Beyond Russia, the party cadres understood that it was open season against the Jews. A Hungarian Jewish leader, Lajos Stoeckler, was arrested by Communist authorities who said that the Joint was even more dangerous in Hungary than in Russia.

The dog-whistle, sounding shrilly from the Kremlin, was heard all over Eastern Europe.

Tyrant’s End

And then suddenly, Stalin was gone. On Friday night, February 28, Stalin had dinner with his henchmen, and the merrymaking went on until four a.m. on March 1, when he retired to his quarters (see sidebar). The next time that the Kremlin bosses saw the Leader, he was dead — a Purim miracle as the day of Haman’s downfall was ushered in.

By the next morning, the news had spread across the Soviet Union. The giant Communist world — from the Politburo down to the most miserable prisoner in a labor camp — held its breath.

Informed of Stalin’s stroke, Rav Yitzchak Zilber took up a Tehillim and prayed for the tyrant’s end. For the next three days, he repeated the entire book again and again, while running to fetch water or sitting in the barracks.

Far away in the Moscow home of Professor Rapoport, who was one of the accused doctors, a terrified mother and daughter huddled by the radio, hoping that Stalin’s end would mean the return of their loved one.

Deep inside the Lefortovo Prison, Doctor Rapoport himself became aware that something had changed for the better when the tenor of his interrogations altered.

“Death seemed inevitable,” he told the New York Times in 1988. “But suddenly the questioners started asking about certain symptoms that indicated a patient had a fatal illness. They inquired about good specialists. But the specialists were all in prison.”

Rapoport was witness to the deadly effects that Stalin’s arrest of the doctors had had on his own health. Even when his fellow Soviet leaders deigned to call for treatment, none was available, because the experts were all being tortured.

Wakeup Call

With Stalin out of the way, the Doctors’ Plot collapsed overnight, and within weeks the doctors were home, officially rehabilitated, but scarred for life.

The sincere mourning of millions of Soviet citizens — for whom the “Sun of the Peoples had set” — didn’t spread to Soviet Jews. Up to that point, Soviet Jews had been grateful to the USSR as the liberator of the Death Camps. But even ardent Communists were shocked by their ordeal into the recognition that they’d been worshiping a false god.

“For years I asked myself why Soviet Jews had to go through this terrible ordeal,” says Rav Benzion Zilber, son of Rav Yitzchak, who was raised in the immediate post-Stalin era, and went on to head Toldot Yeshurun, a large Russian-speaking outreach organization in Israel.

“We can’t know for sure, but perhaps it was a message of Jewish identity — that despite the difficulty of keeping Yiddishkeit in Soviet Russia, at the very least we were expected to remember our own difference as Jews.”

Until this day, Rav Benzion continues his father’s custom of drinking a special l’chayim on Purim in commemoration of the salvation of Soviet Jews, still within living memory.

As de-Stalinization and a brief thaw in Moscow’s reign of terror became a central theme of the Krushchev era, the Doctors’ Plot loomed large in the new leader’s denunciations of his predecessor.

In the so-called “Secret Speech,” an address at a closed-door meeting of the Communist Party’s Congress in 1956, Krushchev shocked delegates by exposing the full extent of Stalin’s crimes against Russia’s people.

The speech was so explosive that it caused a rupture in the Communist world, as Mao’s China denounced the repudiation of Stalinism, and became an unremitting foe of Moscow. There was a race among Western intelligence agencies to procure a copy of the speech, which was won by the Shin Bet, in a coup for Israel’s young intelligence service.

In the speech, Krushchev had dwelled on the Doctors’ Plot, going back to its earliest days with Zhdanov’s death in 1948.

“After the war, Stalin became even more capricious, irritable, and brutal,” Krushchev said to a tumult in the hall. “His persecution mania reached unbelievable dimensions. Let us recall the affair of the doctor plotters. Actually, there was no affair outside of the declaration of the woman doctor Timashuk, who was probably influenced or ordered by someone to write Stalin a letter in which she declared that doctors were applying supposedly improper methods of medical treatment.

“Such a letter was sufficient for Stalin to reach an immediate conclusion that there are doctor plotters in the Soviet Union. Present at this Congress as a delegate is the former Minister of State Security Comrade Ignatiev. Stalin told him curtly, “If you do not obtain confessions from the doctors, we will shorten you by a head.”

But whereas Krushchev would write that Stalin unleashed the Doctors’ Plot because of his anti-Semitism, Jonathan Brent disagrees. “Stalin had already unleashed terror against other national groups — if the Doctors’ Plot had been only about anti-Semitism, he would have moved against them far earlier in his life.”

The late unfolding of this bigotry, says Brent, points to Stalin’s calculated use of anti-Semitism to unleash a wider anti-Westerner purge on society — a plan that had been developed in his cunning mind since 1948.

The Sun of the Peoples: Israel’s Communists swallowed the party line against their own brethren

Hoisted on His Gallows

Whatever Stalin’s diabolical intent, to those who watched the events unfold, there was a sense of poetic justice; that someone who had instigated such a senseless orgy of terror had died, almost literally, by his own hand.

Although Jews across the free world were concerned by the fate of those millions trapped behind the Iron Curtain, it was perhaps Chabad —with its deep Russian roots — where those fears were most acute.

Famously, at the Purim festivities in New York, the young Lubavitcher Rebbe told the story of a chassid who had mistakenly shouted, “Hu Ra! Hu Ra! — He is evil!” — instead of “Hurrah!” at an election speech. The insertion of a story from an event in 1917 was cryptic; but in retrospect it was seen by chassidim as a reference to the downfall of evil as Stalin writhed in his death throes.

That sense of justice at Stalin’s death was felt by observers across the spectrum.

“Joseph Stalin was a manhunter,” said Natalya Rapoport. “His hunting season went on for three decades, but when he directed his boomerang against leading medical scientists and doctors — my father among them — the boomerang suddenly returned.”

With the last elderly witnesses to the effects of Stalin’s diabolical plot still living, the almost-miraculous aversion of the Soviet Holocaust is a story not widely-enough known outside of the Russian-speaking world.

As Isaac Mironovich belatedly realized when he rushed across the Siberian prison camp that Purim morning in 1953, the tale of Stalin’s demise is a story worth telling. Hastened because the Jewish doctors who could have treated him were being tortured in his own dungeons, Stalin’s downfall was an echo of Haman’s hanging on the gallows he’d himself built.

A view of Stalin’s funeral cortege taken from the American embassy

Death of a Dictator

The circumstances around the Soviet strongman’s death will likely never be known. Did he die naturally of a stroke, and was the process aided by purposeful neglect by powerful Soviet leaders anxious to see him gone? Was he poisoned by members of the Politburo, certain that they were next on the aging dictator’s hitlist?

What seems certain is that in the early hours of March 2nd — a Shabbos morning — Stalin finished dinner with his henchmen Beria, Malenkov, Krushchev, and Bulganin, and then went to bed. At six-thirty p.m. a light went on indicating to staff outside that Stalin was working. But then sometime around 10:30 p.m. that night he was found — either by a guard or a maid — sprawled on the floor, having suffered what seemed to be a brain hemorrhage.

The next moves are even less clear. Krushchev — who triumphed in the struggle to succeed Stalin — said that he called for medical help early on March 2nd. Another version has it that it was Lavrentiy Beria — a powerful former NKVD chief — who called medical help, having been unavailable for five hours as Stalin lay senseless.

But some evidence, says Jonathan Brent, point to a far more active role played by someone in Stalin’s death. What wasn’t reported after Stalin’s death were symptoms such as vomiting blood and blue cyanosis — a tinge of gray around the lips. These aren’t consistent with a stroke diagnosis.

Another oddity is the treatment: Stalin was treated with leeches, which act as an anti-coagulant which would treat a stroke caused by a blocked artery. But if there was a brain hemorrhage, then the same treatment has the opposite effect, accelerating the rate of bleeding. The doctors couldn’t have known which it was at that time, making their treatment suspect.

Those questions may point to another possible explanation — one that the Kremlin bosses who succeeded Stalin were anxious to cover up: he was killed.

“If indeed Stalin was poisoned, then Warfarin — a blood-thinner — would have been the poison of choice,” says Brent. “That’s because Stalin was paranoid, and so anyone who ate with him had to taste some of his food. But Warfarin — which was invented in 1950 in Wisconsin and marketed worldwide — is not harmful in small doses. It’s only in elevated doses over a period of five days that it’s deadly.

“So, it’s a perfect poison because anyone at the last dinner could have had a sip of Stalin’s wine and a taste of his kasha and then walked away; only Stalin with the deadly buildup of the blood thinner in his system over a number of days, would have been affected.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.