R

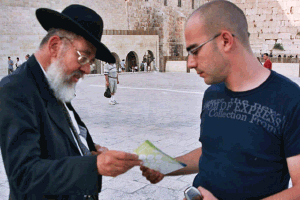

abbi Meir Schuster was more than just a fixture at the Kosel, arranging Shabbos meals for the curious, and accommodations in the Old City for travelers. Colleagues who knew him well and backpackers who met him just once all recognized: There was nothing Reb Meir wouldn’t do to save a Jewish soul.

He had a few standard lines. One was, “Want to meet a wise man?” Another was, ”Are you Jewish? Do you need a place to stay?” In this way, Rabbi Meir Schuster ztz”l, who passed away last week at the age of 71 after a long battle with a neurological disorder, introduced nonobservant Jewish travelers, “just passing through Jerusalem” to Yiddishkeit. His “office,” as it were, was at the Kosel, and he hardly took a day off in nearly 40 years.

Described by those who knew him in his younger years as painfully shy, Reb Meir transcended all boundaries to become one of the most successful kiruv professionals of our time. It is estimated that he brought thousands of Jewish neshamos back to their roots through his work at the Kosel, his Heritage House in the Old City, and Shorashim centers serving Israeli seculars.

In the stories that follow, those who “bumped into” Reb Meir, along with colleagues who saw his work up close, describe their most enduring memories of Rav Schuster.

A Short Detour

Jeff Gordon

My first encounter with Rabbi Meir Schuster was on a visit to the Kosel. My future wife and I had just come to Israel after spending five months backpacking through Asia, and Rabbi Schuster was called over by a kiruv worker at the Kosel who had just helped me put on tefillin. A man of few words, he made us a simple offer: “Would you like to go and hear a holy man speak?”

We saw no reason not to accept his offer, and the next morning, he was waiting for us outside our youth hostel at 9 a.m. He drove us to Aish HaTorah, where we sat in on a lecture given by Rav Noach Weinberg, and then he made another interesting offer to my future wife: “How would you like to hear a class given by a woman?” When she acquiesced, he drove us across town to Neve Yerushalayim, where we both sat in on a lecture delivered by a famous rebbetzin.

We thanked Rabbi Schuster for his help and informed him of our plans to spend some time resting on a kibbutz, but he wasn’t finished yet. “Why don’t you stay in a yeshivah here to rest, instead?” he suggested. “You can stay as long as you like, and you,” he added, turning to my wife, “can stay in a seminary.”

The very next morning, Rabbi Schuster was waiting for us outside the hostel once again. Before dropping us off at our respective destinations — Aish HaTorah for me and Neve Yerushalayim for her — he offered to hold on to our plane tickets for safekeeping. We had a pair of open tickets that were valid for any TWA flight to the destination of our choice, up to a year from the date of issue; such expensive documents, he told us, should be kept in a safe place.

“I’ll give them back to you when you’re ready to leave,” he promised.

Over the next few months, he visited each of us regularly, checking on our progress and making sure that we were happy and thriving. On weekends, he regularly arranged Shabbos meals for both of us, making sure that we could spend Shabbos together. We were thrilled to be learning more about Judaism, but as the expiration date of our tickets drew near, we informed Rabbi Schuster that we would have to leave the country soon. The rabbi, however, wouldn’t hear of it.

“I have a connection with the airline,” he told us confidently, “and I can see to it that you can extend your tickets.”

The tickets themselves warned that they could not be extended under any circumstances, but Rabbi Schuster was undeterred. He managed to convince us to remain in Israel, and when we were finally ready to leave, he presented us with a pair of valid airplane tickets for our return trip.

At the time, we naively believed that the rabbi had, indeed, managed to orchestrate some sort of maneuver behind the scenes and convince the airline to extend our tickets. Years later we learned the truth: He had personally raised the money to buy us new tickets, while our old ones had expired. Rabbi Schuster was always amused by the fact that we had actually believed his story.

If he had been the domineering or aggressive type, it’s doubtful that he would have accomplished what he did. But Rabbi Schuster transformed our lives with only a few simple words here and there, igniting the process of that transformation simply by offering us the chance to attend a class.

One of his greatest moments of nachas came when we visited Eretz Yisrael for the summer years later and rented an apartment in the Old City, where we stayed with our older children. Every week, Rabbi Schuster would bring a few Shabbos guests to our home. He beamed with pleasure at the way our lives had come full circle: Once, he had been setting us up for Shabbos meals, but now, we were the ones offering our hospitality.

—Jeff Gordon, a father of six, lives in Monsey and is the owner of The HealthSearch Group, a nationwide executive recruiting company.

He Never Wavered

Rabbi Avraham Edelstein

Rabbi Meir Schuster was a giant in kiruv. Like all of the great founders of the baal teshuvah movement, he will never, can never, be replaced. Rabbi Meir Tzvi Schuster was produced by his era, but he also shaped it. For over three decades, it was he who single-handedly filled many of the baal teshuvah yeshivos.

By the end of his healthy years, Reb Meir had built up an empire of sorts: Two Heritage House hostels (one for men, one for women) with year-round activity, ten Shorashim branches for Israeli youth. Yet, the amazing thing is, for all he built up, he never got distracted. He never became an institutional man. He stayed at the Kosel, or on Ben Yehuda Street, or visited an Arab hostel in the Muslim Quarter late at night to try to persuade Jewish kids to come and stay in his Jewish hostels. He did this in the blazing sun and the freezing cold, often getting soaked. He did this seven days a week, coming every Friday night to place kids with families, and returning in the morning (an hour’s walk from his home) to place whomever had showed up for the lunchtime meal. He was there on festivals and he went with his family to be there over the High Holidays. He never complained, he never took off his hat and jacket in order to present a “friendlier face,” and he never wavered. He stopped only because he got a degenerative disease that left him incapacitated.

Several times I saw Reb Meir (as we fondly referred to him) leave one or another of the Heritage House’s most important donors in midsentence without warning. He had eyed a backpacker and he was off. But everyone understood that this man was committed to a higher mission and that he would sacrifice making a good impression to save a Yiddishe neshamah.

There was nothing that he did not do with almost a nerve-racking intensity and a profound simplicity. That intensity was directed straight at the Ribbono shel Olam. As time went on, he seemed to be driven by the terrifying idea that there were Jews intermarrying every day: That thought kept him in a perpetual state of dissatisfaction with what he had achieved up to that point.

I have met many people who care deeply for the Jewish People. I have never yet met someone who translated it into the deeply personalized caring for every Jewish soul that was Reb Meir’s way. He would fork out money to buy people new airline tickets (and tell them that he had managed to change them so that they wouldn’t feel bad) to give them the chance to go yeshivah. When someone left for home, he would ask them to hand deliver a letter to someone in their area. Invariably, and unbeknownst to its messenger, the letter would ask the recipient to look after the person in front of him. He would never give up on anyone, never tire of asking someone, for the umpteenth time, if they wanted to go to a class — just one. And he would take them there and pick them up himself.

There are so many unusual stories about this man and about the people he affected for life. But his daily routine wasn’t about the exotic. If he had dropped someone off at yeshivah or seminary, he would look them up every day to find out how they were doing and whether they needed anything. Reb Meir’s greatness ultimately lay in the smallest deeds: in the consistency and daily pursuit of his cumulative acts of sensitivity and profound commitment to each neshamah. There was nothing complicated about what he did. He just did it every moment of his life.

And now he is gone.

—Rabbi Avraham Edelstein is a founder and director of the Ner LeElef Institute for Leadership Training and a founder of and senior advisor to Morasha Olami. Rabbi Edelstein was executive director of Rabbi Schuster’s Heritage House for 20 years.

Answered Prayer

Chaim Tzvi Felder

My nonreligious hosts strongly recommended, in addition to the series of Egged Tours I had booked for my Israel trip, that I arrange to spend a Shabbat in Jerusalem. Looking through the telephone book, I somehow ended up at a hotel called the Ritz, and booked a room for Friday and Saturday nights.

When I arrived in Jerusalem that Friday, which happened to be Rosh Chodesh Elul, I couldn’t help feeling impressed with the special atmosphere of the place; there was an extraordinary but intangibly wonderful feeling in the air. I was only disappointed to find out that the Ritz was located in the Arab quarter.

After checking in, I decided to walk to the Western Wall. Though I had a guide book with me, it was still rather confusing to find one’s way in such unfamiliar surroundings. Nevertheless, after entering the Damascus Gate, I kept walking straight, according to the guide book’s instructions. Suddenly, I came to a security check, and once past it, all of a sudden the Wall appeared unexpectedly before me.

At that moment, I was overcome with a tremendous awe, as if I were entering into the court of a great, mighty, but unseen King. I felt the awesomeness of this Presence so strongly that I could only approach the Wall very slowly. When I had finally reached it, I pulled out a pocket siddur and began davening Minchah. Though I didn’t daven daily in those days, this seemed like a particularly auspicious occasion to do so. It was done with deep devotion, with tears mingled with sweat from standing in the hot sun.

No sooner had I finished than a man called Rav Schuster suddenly walked up to me and offered me Shabbat hospitality. It was as if my real prayer were answered before it had even been formally expressed, as I hadn’t mentioned this need in my prayer at all. Yet Hashem peered right through the unhappiness over my quite unsatisfactory sleeping arrangements. So I accepted immediately, but told him I had to return to my hotel to check out and get my luggage. When I returned to the hotel, they were kind enough to return my money and accept my checkout without any problem, and I took a taxi to the place Rav Schuster suggested.

He lived in one of the new religious neighborhoods that had been built at that time. When I first arrived, I could see lots of children running around, all the boys with black kippot and peyot, and the girls with lovely dresses, something I was not familiar with in those days. Apparently used to strange visitors, they helped me to the Rav’s place, where I spent a most lovely Shabbat. For Friday night he arranged for me to spend at a friend of his in the area, and the rest of the time I was with him. It was quite a moving, inspiring experience.

—Clifford “Chaim Tzvi” Felder z”l, featured in Issue 468, made aliyah a few years after getting the proverbial tap on the shoulder at the Kosel from Rabbi Shuster. Felder was a Rehovot resident and a leading research chemist at the Weizmann Institute until his passing in January 2013.

Straight Talk

Freida Shapiro

A year before I became frum, I was entering the Old City with a friend after Birthright trip, days before my brother’s wedding, and I was planning to look for the supposedly free-for-Jews hostel (having stayed at an Arab hostel in Haifa the night before), but had no clue where to find it. We actually doubted it even existed as we stood at the edge of the Old City. I was wearing a black tank top and purple pants (cringe).

Rabbi Schuster, who really scared me at the time, emerged out of nowhere and said, “Are you Jewish?” And when I stuttered that I was, he literally took my giant suitcase and wheeled it to the women’s Heritage House with no explanation — we ran to keep up with him, despite his age.

The next day he showed up bright and early to drive my friend and me to Neve Yerushalayim. On the way from the Old City to Har Nof, he asked us what we were doing with our lives. I told him that I was an actress, and instead of the “Wooooow, what stuff have you done?” and the like that usually came in response, he said, “What, why would you do that? Don’t you care about your future? Having a family? Don’t you care about your Judaism? You need to think with your head, not your stomach!”

I was furiously indignant. Like “you don’t know me!” type of indignant. No, I wasn’t thinking about having a family — I was 19! And my Judaism was fine, thank you! Yet we eventually got out at Neve, and learned real Torah for the first time that day, thanks to him.

His criticisms echoed with me for the entire year that I was back in New York doing theater, and the next summer I ended up on Jewel, at Neve, and eventually worked as a madrichah for Jewel, Neve, and yes, the Heritage House.

As a madrichah at the Heritage House, I helped host all the participants for Shalosh Seudos every Shabbos, and Rabbi Schuster was always there, handing out challah, telling people to wash (often answered with “What? Why?!”) It was always amazing to witness that he cared as much about his own Yiddishkeit as anyone else’s. When we sang zemiros (often it was him by himself, or with one or two madrichim, since no one in the room had ever heard zemiros before) he pronounced every word slowly and clearly. And bentshing was the same — he savored it.

I had surmised over the course of being exposed to Yiddishkeit that front-line kiruv was for hip, charismatic people who could almost trick people into seeing Orthodoxy as cool, and that later in their journey they would get all their answers and see the real Torah world as cool since they had gradually acclimated to it. But it wasn’t true. Rabbi Schuster always looked like he walked out of Bnei Brak. He was the master at kiruv and had no charisma in the conventional sense. He was simply a shaliach of HaKadosh Baruch Hu — he literally was mevatel himself for the purpose of preserving the Jewish People, at every moment. He didn’t need any extras or any talents. He had ratzon and he was literally unstoppable.

I’ll never understand why I followed him in the Old City that first day (except that he had my luggage... but I could have grabbed it back). It was totally out of character for me. And you would think that his comments about my chosen path would have turned me off from Orthodoxy, but they somehow didn’t. Once I calmed down (it took a while), I realized that no one had ever criticized my life choices that way in the secular world. He cared about me enough to say something about my future, my real future: not my career, but my neshamah and the family he wanted me to build. I hadn’t dared to dream that big about my life before.

He should continue to be a meilitz yosher for Klal Yisrael in the Next World, just as he was in This World.

Love For Every Jew

Rabbi Yehudah Silver

As one contemplates the accomplishments of the great and humble giant, Rabbi Meir Schuster ztz”l, what becomes evidently clear is that they give testimony to the power and majesty of siyata d’Shmaya, Hashem’s providential guidance. It gives us irrefutable evidence that there is no challenge, no frontier or boundary, that a Jew can’t conquer with Hashem’s help.

I remember when Reb Meir first came to the yeshivah in Chicago, from Milwaukee. He was a shy, bashful teenager who found it almost painfully difficult to communicate. Yet I had an overwhelming sense that under his shyness there was a deep and passionate love for HaKadosh Baruch Hu and His Torah. Soon after he left Chicago for Yeshivas Ner Israel in Baltimore, I left for Eretz Yisrael; I don’t think I saw him again until 1983 or 1984 when I was working in Aish HaTorah in the Old City of Yerushalayim.

No one can know what another person is feeling deep inside himself. However, what one saw on the outside with Reb Meir was a person who was at ease and comfortable with persuading young people to taste the sweetness of Torah. There is no question in my mind that it stemmed from an unswerving dedication and commitment to fulfilling Hashem’s Will. He was living proof that we all have latent potential that can be actualized when we choose to tap into it and together, with Hashem’s help, we can overcome any limitation.

This was Reb Meir Shuster. He knew what Hashem wanted and his heart was full of overwhelming love for every Jew. He understood what had to be done and he rose to the challenge.

Yehi zichro baruch.

—Rabbi Yehudah Silver, a lifelong Torah educator, was the director of outreach programming at Aish HaTorah in Jerusalem and founded and directed the Discovery Seminar. Rabbi Silver has lectured extensively throughout North America, Israel, Europe, and South Africa for Arachim Seminars.

A Personal Touch

By Avraham Lewis

“Let’s go!” Rav Meir Schuster exclaimed, racing out of the house toward the waiting car. I hurried after him, clutching the keys. “Start the engine and let’s go!” he repeated with fervor as soon as we were seated.

“But which direction should we go?” I asked as I slipped the keys into the ignition. “Should I drive forward, or should I turn around and head the other way?”

Rabbi Schuster, though, could not be bothered with such trivial concerns. “Just go!” he said firmly, emphatically, giving voice to his deep-rooted drive to take action.

This exchange was repeated numerous times over the course of our shared fundraising trips to America. Four years ago, as Rabbi Schuster was growing increasingly ill, I was asked by the Heritage House to accompany him on his travels overseas, both to assist him in his efforts and to care for him over the course of his journeys. On each trip, I found myself whisked into a nonstop whirlwind of activity.

It would begin at the airport in Israel. Due to his illness, Rabbi Schuster had a tendency to forget where he was and to wander away, and I was responsible for keeping an eye on him. Inevitably, he would use his time in Ben-Gurion Airport to approach Israeli travelers and offer them a card with the various addresses of Hebrew-speaking Shorashim centers, urging them to visit and attend classes. Many of them were surprised or perplexed by the elderly stranger who approached them — speaking in his limited Hebrew — but somehow, he still managed to make an impact on them. There was something endearing, even compelling, about the way he interacted with people, and his natural charm often broke through the most rigid barriers.

There were fewer Israelis in airports outside of Eretz Yisrael, which made it easier for me to keep track of Rabbi Schuster. But when we arrived at our hosts’ homes, he was back in perpetual activity mode, always eager to be on the move. If a donor didn’t answer the phone when he called, Rabbi Schuster would insist on driving to their home, despite my protestations that it might be construed as impolite. And as soon as the door was opened, even if it was by a maid, he would stride directly into the house, eager to get down to the business of fundraising.

Rabbi Schuster had hundreds of regular donors who made contributions of varying amounts, some as little as $50, but he made sure to visit each one personally. To the average fundraiser, this may seem like a waste of time and resources; that was certainly my sentiment, and on a recent fundraising trip, I tried to change the situation. Rabbi Schuster’s health had deteriorated to the point that he was no longer capable of taking the trip, and I went on my own, resolving to visit personally only those donors who regularly gave more than a certain amount.

I began making phone calls from my accommodations in Brooklyn, armed with a list of 60 individuals who had given impressive donations every year for the past 20 years. Yet, despite repeated attempts over the course of seven days, I only managed to reach two out of those 60 people. Apparently, Rabbi Schuster’s own efforts had been blessed with an enormous amount of siyata d’Shmaya, more than the average person tends to receive. Then again, that was only fitting for a man of such unusual dedication.

—Avraham Lewis worked at the Heritage House as a volunteer during his yeshivah years and has recently begun helping the organization raise funds.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 499)