Siberian Saga

Whether it was the beard — Soviet Russians showed extra respect to bearded men — or the merit of mesirus nefesh for Yom Tov, Shlomo Klapper got out of jail that night

It was just the judge, the prosecutor, and Shlomo Klapper in a Siberian courthouse that frigid Friday night in 1940.

Reb Shlomo, a sawmill laborer, was accused of missing work over Yom Tov.

“Judge, do you see this man?” the prosecutor pointed threateningly at Reb Shlomo. “He looks innocent, doesn’t he? But he didn’t come to work on these days”—here he pointed to Mr. Klapper’s work calendar—“and because of that, the generator did not have enough wood. Because of that, the electricity was reduced, and because of that, the people who worked in the gold mines didn’t have enough electricity. Since they mined less gold, the people in Moscow couldn’t supply the Red Army, and because of that, our brave Soviet soldiers couldn’t properly defend the Motherland. All because of this man…”

The judge looked gravely at Shlomo, waiting for his defense.

“Honored judge, I would never let the brave Soviet soldiers down. Just look at this document.” Shlomo proffered a document signed by his supervisor. “The soldiers did not suffer. Just the opposite — I worked twice as many hours to cover those days that I missed.”

Shlomo looked up at the judge, awaiting the verdict. Rarely was anyone released from a Soviet “kangaroo court,” so Shlomo knew his chances ranged from slim to nonexistent.

The judge studied the bearded man before him, perused the document again, and lapsed into thought. And then, the verdict:

“Not guilty. Case dismissed!”

Whether it was the beard — Soviet Russians showed extra respect to bearded men — or the merit of mesirus nefesh for Yom Tov, Shlomo Klapper got out of jail that night. Shlomo, that gentle talmid chacham, continued onward to devote his life to Torah and mitzvos, and to taking care of his fellow Jews — from the frigid tundra of Siberia to the humid heat of Kazakhstan, from the poverty of DP camps to the plenty of America. This is his story.

Born in Jarocin, a village in Galicia, in 1901, Shlomo Klapper’s childhood was spiritually and materially comfortable. His father, Reb Ephraim Tzvi, was a Rozwadower chassid and landowner in the small village; they were considered well-to-do by village standards.

World War I shattered Shlomo’s peaceful life. Just after his bar mitzvah, the Russian military transferred his family into the interior of Russia, hoping to exchange them for Russian prisoners of war. But the turmoil yielded some unexpected benefits. Toward the end of the war, his family was freed and relocated to Tarnopol, Poland, just outside the Russian border, which was graced at the time with an illustrious resident: Rav Meir Shapiro of Lublin.

Rav Shapiro had organized a small elite yeshivah, and teenage Shlomo fervently wished to be admitted. But that was no easy task. Admission was limited to outstanding students. Shlomo learned Maseches Yevamos by heart, passed the farher, and got in. Yevamos is one of the most difficult masechtos, in part due to its in-depth treatment of the complicated laws of agunos. When Rav Shapiro was called upon to be matir agunos in the wake of World War I, he recalled Shlomo’s proficiency in Yevamos and invited him to join him in that mission. Rabbi Dovid Sheinfeld, whose father-in-law Rav Shaul Dovid HaKohein Margulies was the third member of Rav Shapiro’s agunah beis din, wrote later about Shlomo that “he knew siman yud-zayin [the siman about agunos] literally backward and forward.”

After World War I, Shlomo’s father decided that chinuch opportunities in Jarocin were inadequate for his growing family, so he joined his extended family in the nearby town of Ulanow. About half the town’s population was Jewish. “In Ulanow, even the horses wore shtreimlach,” Shlomo’s son Yaakov later quipped.

But for Shlomo, the quiet, shy talmid chacham, life did not stay settled for long — it was time to find a shidduch. A distant cousin suggested Machla Schlissel (a descendant of Rav Akiva Eiger) from Kanczuga, Galicia, and they met at a relative’s home at the halfway point of Lizhensk. But Machla’s brothers, who had joined their father and sister for the meeting, wanted to be sure that this prospective brother-in-law deserved his reputation as a lamdan. To this end, they surreptitiously removed their host’s copy of Maseches Yevamos from the bookshelf.

“I’ve heard you’re an expert in Yevamos,” Machla’s father began. “Would you like to learn with me a little bit?”

Yevamos was missing from the shelf, but this was no problem for Shlomo. He still remembered that masechta from his entrance farher, a few years before. He proceeded to quote, explain, and discuss sugya after sugya from memory, much to Machla’s family’s astonishment and delight.

Shlomo had passed his first test, but he still had a second one — with Machla herself — and that would be no easy feat. They strolled outside for a few minutes, where “of course all the neighbors looked out the windows,” their son Yaakov recounted with a chuckle many decades later. But Shlomo, Machla’s junior by two years, was too timid to start the conversation. After walking in absolute silence for some time, Machla decided to take charge of the situation (a trait that would characterize her later on). Although she had been brought up in a chassidishe home, Bais Yaakov had not yet opened its doors, so she had gone to the Polish gymnasium.

“Have you read Goethe and Schiller?” she asked, referencing the celebrated German writers.

“No, I spend my time with Abaye and Rava,” Shlomo answered, thinking the shidduch was probably done for.

But he had underestimated his future kallah. So impressed was she with his devotion to learning and his refined nature, they got engaged that very day. Shlomo used the dowry he received to open a textile store in Ulanow. He did not want to make Torah a “spade to dig with,” but, between customers, his Gemara was always open.

At the outset of World War II, the Soviet Union ceded Ulanow to Germany in the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact. The townspeople sought any and all means to flee eastward to Soviet territory, before the Germans arrived. Shlomo procured a horse and wagon, loaded up his family and possessions, and prepared to set out for Lemberg. But the shy talmid chacham, though wise in the ways of the Talmud, was less at home in the ways of the world. He did not recognize that the horse he had purchased was meant for riding — not for pulling a wagon. No matter what Shlomo did, the horse refused to budge. So the more practical Machla took charge. Since nobody believed the Germans would hurt women and children, she told her husband and eldest son Moshe, then 15, to go ahead by foot. She would remain with the younger children and catch up as soon as possible.

Shlomo and Moshe made it to Lemberg safely. He immediately sent for his wife, but her crossing into Soviet territory was at that point no easy task. Soviet troops had closed the border hours before she arrived with her children. But Machla was not a person to be easily defeated. She hired a peasant to take them, together with their possessions (including a washing board!), across a river to the Soviet side. She planned her crossing for midnight — and arrived safely in Lemberg.

In Lemberg, Shlomo made a living on the black market. There was no regular commercial market there during wartime. The government had outlawed most forms of business, and left people the choice: Buy and sell illegally, or starve. The Klappers hoped to remain in Lemberg until the war’s end, but a summons from the Soviet secret police in the summer of 1940 dashed their plans.

The Klappers didn’t know it at the time, but the summons saved their lives. The secret police were there to deliver an ultimatum, though couched in polite terms: Become a Soviet citizen, or return to Poland. Shlomo realized that accepting Soviet citizenship would place his family too firmly beneath the Communist yoke. But returning to German-occupied Poland was not an option either. So he simply requested to remain at status quo: a Polish refugee. The officers knew what they had to do. They smiled, recorded Shlomo’s answer, and let him go.

Shlomo was relieved, glad that the interview had gone so smoothly. But he was badly mistaken. At two o’clock in the morning, a few weeks later, there was a knock on the door — the secret police. They gave Shlomo, and the entire extended family residing there, a half hour to pack up their belongings. Where were they going? The police refused to tell them.

The police took the Klappers to the train station. But their journey was not high priority, so their train sat there for two days before departing. The Soviets did not accord their prisoners regular means of transport, either — the train cars were meant for conveying horses, and the Soviets had added shelves to each car to accommodate more people. That meant everyone had to sit or lie down for the entire journey, a matter of several weeks.

But while waiting on the tracks, still unsure of their destination, the family received a heartening visit. Tante Esther (Mayer), Shlomo’s sister, was living in Lemberg with her husband’s family, somewhere separate from the rest of the Klapper clan. She was unaware of her family’s arrest, until word spread around the Jewish community that that they were at the train station. She rushed there with her husband to see what they could do. Shlomo was not easy to find — the train cars had no windows, and each one was crammed with people. But she searched through every compartment until she finally found him.

“Where are they taking you?” Esther demanded from her brother.

“We still don’t know,” Shlomo replied. “Possibly back to Poland.”

Tante Esther looked at her husband Leibush, and then back at her brother. Then she made up her mind.

“Well, I don’t know where they’re taking you, but if that’s where the family’s going, that’s where I will go too.”

It was a decision that saved her life.

The train ride took weeks. At every station, troop trains and freight trains and passenger trains moved out while the Klappers’ train remained idle. Only when all the important trains had left were the prisoners permitted to depart. The one advantage to these waits was that at certain points, the Soviets allowed the passengers to get off the train for fresh air — under heavy guard, of course. When the train stopped in Brody, the Klappers sent a message to Machla’s brother who lived there — he brought them a large sack of sugar, which they used to garnish their coarse bread that entire winter.

At a different stop, they asked a peasant woman if she had any idea where they were headed.

“Siberia,” she responded.

They thought she was joking. It was the most horrible place anyone could think of at the time, but it turned out to be their salvation from a much worse fate — the German takeover of Lemberg.

To the family’s shock, they soon discovered that the peasant woman was right. After four weeks of cramped travel with the barest minimum of food, they arrived at one of the furthermost reaches of Siberia, bordering Manchuria. The Soviets put them up at a “hotel” for the night, where sleep was impossible, due to the other “guests” in the room — a horde of bedbugs.

But the hotel experience was only for one night — the next day, the Soviets packed them into trucks, and drove 400 to 500 miles north into Siberia’s frigid interior. The villages where the Klappers ended up — first Yakakustroi, and then Amerikanka (named for the gold mine there that Americans had leased before World War I) — needed no police to guard against escape. There was no hope of escaping; they were surrounded by frozen, forested mountains, and the nearest train station was hundreds of miles away.

The frigid conditions made the prisoners’ jobs extremely dangerous. Workers had to show up unless the air was foggy outside the barracks’ windows. (The fog meant that temperatures had dropped below minus-55 degrees.) Luckily, Shlomo’s job was not in the forest, where workers had to trudge through knee-high snow to reach their job sites. He worked in the village, cutting timber with an electric saw. When the lights dimmed back home in his family’s room, they knew he was cutting a particularly large tree. But it was in the evenings that Shlomo was able to return to his real passion — learning — with the small Gemara he had smuggled from Ulanow.

Shabbos observance, interestingly, was not an issue in Siberia — Saturday and Sunday were both given as days off. And when Shabbos came in early on Friday, Shlomo arranged with his supervisor to start his job earlier in the morning so he could leave before sunset. But avoiding work on Yom Tov was quite another matter. When Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Succos of 1940 all fell out on weekdays, Shlomo realized that avoiding work was going to be a major hurdle.

One man in the barracks suggested rubbing a thermometer vigorously to make it seem that he had a fever. But Shlomo was not comfortable with such deception. Since he was on good terms with his supervisor, he came up with a different plan: He offered to work on Sundays for double the hours he’d be missing. The supervisor agreed, and signed notes when the hours were complete. These notes would later save Shlomo’s life when his case came up in the kangaroo court.

Food, too, presented an ongoing problem. Meat, of course, was out of the question for Shlomo’s family. They could buy a small amount of bread, but even that was so coarse it was barely edible. The two items that were readily available in the wild were summer blueberries and rhubarbs, so the family collected vast amounts of them and stowed them in bags under the snow. It was such sparse fare, though, that they feared their teeth would fall out from vitamin deficiency. The locals recommended eating garlic. The family wrote to their uncle in Brody to send some, and he did — though it arrived so frozen, it looked more like crystals than the herb they were expecting.

But the family got used to living with less. All through the winter months, they siphoned off some of their precious flour rations for baking matzos. Shlomo organized baking the matzos, using the small furnace in his barrack room. And at his son Yaakov’s bar mitzvah, there was no food served at all. Shlomo managed to obtain a tiny, kosher set of tefillin, and he organized a clandestine minyan. To celebrate, each guest received a cigarette.

But despite the daily deprivations, Shlomo’s children do not recall those years with bitterness. For a while, Shlomo was a mine worker, carting gold in a wheelbarrow to be cleaned in a nearby river. Due to the strenuous nature of this work, he received a generous ration, two slices of white bread. Every day, when Shlomo’s youngest, Arnie, came to visit, he found, without fail, that his father had saved one of those precious slices for him. It was a sacrifice he never forgot.

In Siberia’s difficult circumstances, young children had to act with an inordinate amount of maturity. Yet, despite these high expectations, Shlomo never lost sight of the fact that they were children. At age 14, Yaakov was in charge of picking up the family’s daily bread ration. One day, he discovered the Soviets had allotted each family a pound of cookies in addition to their regular fare. Yaakov hadn’t had a sweet for years. On his way home, he tasted first one cookie, then another. Two blocks from home, he was mortified to realize the box was empty.

“But my father did not upbraid me,” Yaakov recalls. In fact, throughout the years of Siberia and afterwards, Shlomo’s children could never recall him raising his voice — his mode of chinuch was always marked by gentleness.

Shlomo was a pillar of selflessness, and not just for his immediate family. Through the months of imprisonment in Siberia, many Jews in Shlomo’s village began to despair of ever making it out alive.

Mr. Fass, Shlomo’s partner at the sawmill, would confide his worries to Shlomo on a nearly daily basis: “They’ll never let us out of here,” he morosely predicted. Mr. Fass was seeking encouragement, and of that, Shlomo had seemingly endless reserves.

“When the Russians took us in World War I,” he liked to remind Mr. Fass, “they eventually sent us back to Poland.” In time, though, when Shlomo realized that this mode of chizuk was not working, he decided to try a bit of reverse psychology: “You know, you’re right. We’re never going to get out of here.”

The man’s concerns miraculously melted after this pronouncement.

But one day, in July 1941, they were let out. Due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Polish citizens imprisoned in Siberia were permitted to leave — due to an agreement between the Polish government in exile and the USSR. But there was a catch: they had to remain in the Soviet Union. The family first tried the large town of Aldan, where Shlomo made a comfortable salary working in a gold mine, but the government in Aldan made him put his children in a non-Jewish boarding school.

So Shlomo decided to find a new port of call. But where could they go? Shlomo’s son Moshe, then 17, found a large map of the Soviet Union, and searched for a place that was warmer than Siberia, though not unbearably hot. He finally settled on the city of Dzhambul, Kazakhstan.

“The Hot Country,” as the family came to call it, was completely different from the freezing fortress of Siberia. The living conditions were much improved, but not perfect. The Klappers rented a room from a Tartar Muslim, with a dirt floor, and a cow next door for company. To pay their rent, Machla sold used women’s clothing and shoes on the black market. The Communist Party expected its women to wear drab uniforms, but, in Dzhambul, these ladies craved more feminine attire, at least to wear at home. Machla served as a broker between high-ranking Communist women and refugees with used fancy clothing to sell.

But the biggest boon of life in Dzhambul was its religious freedom. The Klappers, like many Jews who sheltered there, were considered free Polish citizens, so the Communist police unofficially sanctioned their observance of Yiddishkeit. This enabled the Sadovna Rav to establish a minyan, a Gemara shiur, a kosher slaughterhouse, and a mikveh — and Shlomo happily took advantage of the manifold opportunities. Even when able-bodied men were being kidnapped from the streets to work in coal mines — practically a death sentence — Shlomo made sure to never miss a minyan.

When the war ended, the Klappers traveled to Silesia, where anti-Semitism was rumored to be less intense. But Silesia’s repatriated Poles would gleefully pull Shlomo’s beard as they passed, so the Klappers moved on to Bad Reichenhall, a DP camp in Bavaria, where they planned to wait for permission to emigrate.

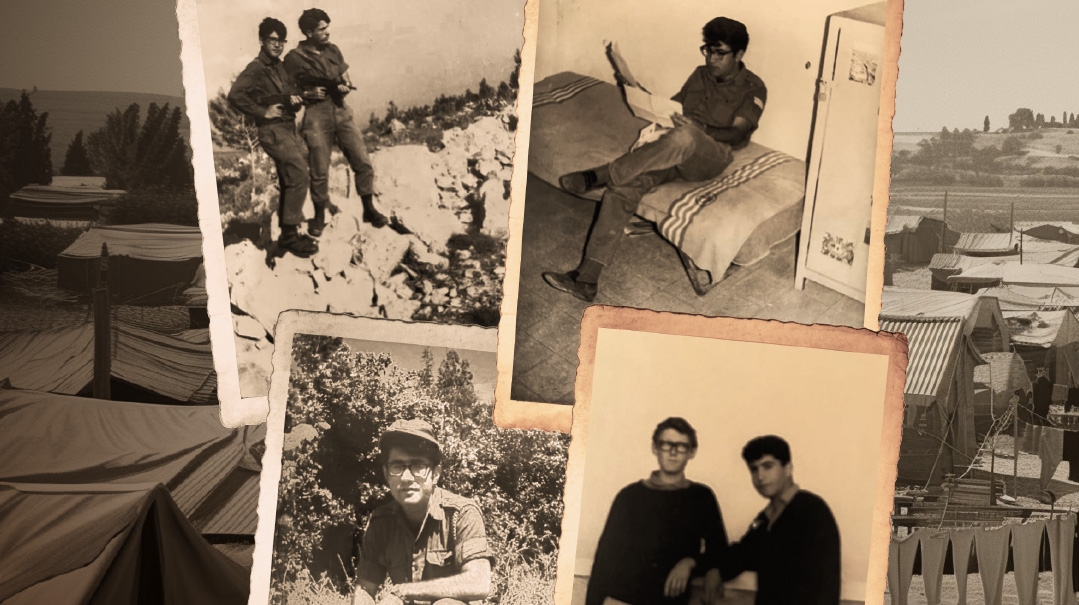

Bad Reichenhall had once been a beautiful resort town. But for the thousands of Jewish refugees living in military barracks, it was overcrowded and dirty — each family had one room to themselves. When Shlomo’s daughter Toby got married to Isaac Fink in the DP camp, the Klappers put heavy furniture through the center of their room to afford the new couple privacy. And while the camp had some amenities, for Shlomo’s teenaged son Yaakov, a most important feature was missing: good reading material. The only books he could find, in fact, were Nazi propaganda ones left by fleeing Germans. Leafing through one, which appeared to be a physics textbook, he was dismayed to discover that all the worthwhile theories of Einstein were apparently “stolen” from Aryan scientists.

While the Klappers waited for months for their American visas to arrive, Shlomo’s refinement and reputation as a lamdan began to draw notice in the camp. He cared about people’s problems, and many felt he would be an ideal candidate for president of the camp’s Agudah. Shlomo had no interest in a public role, but Moshe, Shlomo’s eldest, persuaded him to accept the position, hoping that it might help the family secure their visas sooner. Shlomo saw to the religious needs of Orthodox inmates, such as procuring raisins for Kiddush wine from the American organization Ezras Torah. But the public side of his job — greeting foreign dignitaries to the camp and giving speeches on the dais — was not to his taste. He resigned after a year, and went back to sitting with his Gemara.

It was not until 1949 that the Klappers finally set sail for America, on the US Navy transport USS General Haan. But their travails were far from over. Their passage was free, but the captain demanded that the refugees work in exchange for their passage — including on Shabbos. So the Klappers signed up to change light bulbs. Their reason: bulbs break only infrequently, so they’d probably be spared from working on Shabbos.

Their journey indeed passed without incident — but their landing was not as smooth. The boat docked in Manhattan on Friday the 13th, and the superstitious skipper kept everyone aboard until the inauspicious date was past. When Shabbos morning arrived, though, he demanded that all passengers disembark. Shlomo refused to comply. After a lengthy exchange, the family was allowed to remain on board until Motzaei Shabbos.

Shlomo’s life was filled with adventure, danger, and courage. But for his family, his life was not defined by the difficult times. Shlomo’s granddaughter Rachelle remembers sleeping over at her grandparents’ house in Boro Park, where she would be lulled to sleep on the couch by the sing-song of Shlomo’s learning.

When she awoke in the morning, he was still in the same spot, learning. “But as soon as I so much as blinked, he came right over and asked what I’d like for breakfast.” For Shlomo’s children and grandchildren, his legacy is unceasing devotion to learning, and his gentle, ever-present devotion to them.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 779)

Oops! We could not locate your form.