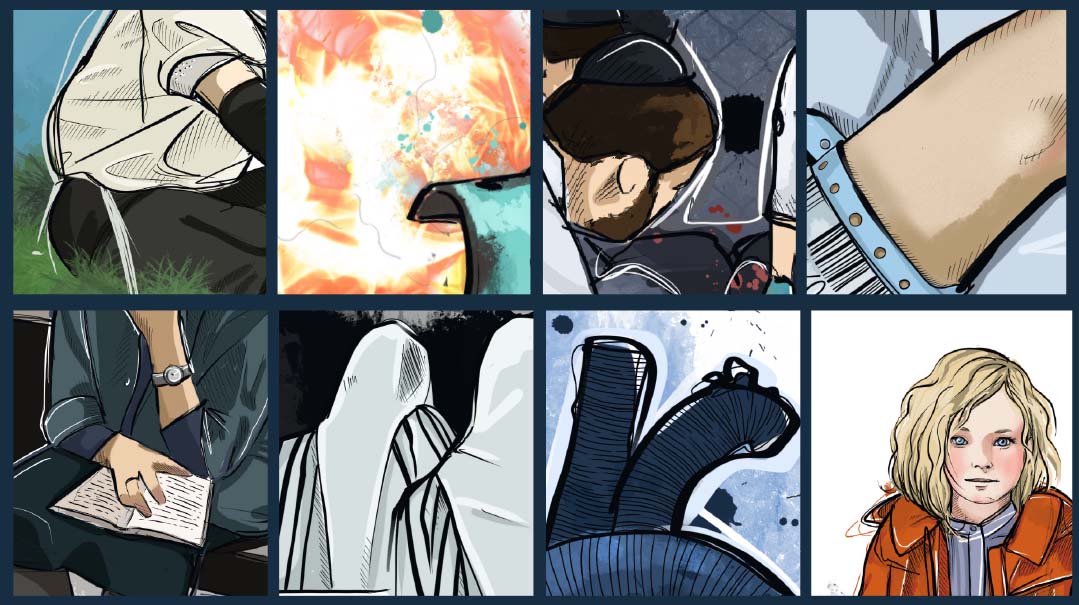

Shot Down, Lifted Up

I opened the door — and found four men on the steps: my father-in-law and three Hatzalah members

“Hey, I’m the wife of the man who was shot. If you want the story, drive me to the hospital”

I’ll never forget the first time our oldest went to Shabbos Shacharis with my husband.

“Efraim Shalom wants to come to shul with me,” Eliahu said that Shabbos Chazon morning 16 years ago.

“Bring breakfast,” Eliahu instructed.

Efraim Shalom, then seven, packed some Cocoa Pebbles in a bag, and the two of them left to Yeshiva of Far Rockaway, a three-minute walk from our home. Eliahu remembers it was scalding outside, one of those stifling August mornings, and eerily silent.

I had told the women on my block that because Sunday was Tishah B’Av, and we wouldn’t be hanging out, they were invited for coffee and cake at my house 9:30 Shabbos morning. At nine a.m., one friend came by — she had heard about the get-together, but didn’t know what time it was called for. Ten minutes later, there was another knock on the door.

“Why bother setting a time if no one comes then?” I mumbled as I rushed to see who was there.

I opened the door — and found four men on the steps: my father-in-law and three Hatzalah members, one of whom was Uri Katz, a family friend. I immediately realized that Eliahu and Efraim Shalom weren’t with them, even though Eliahu davens with my father-in-law.

This isn’t good, I thought.

“Come, let’s go inside, it’s hot,” Uri said.

I was having none of this “break it to you calmly” stuff.

“Just tell me what happened.”

Uri hesitated and glanced around.

“Eliahu and Efraim Shalom were walking to the yeshivah when a masked man approached them near the dumpster behind the public-school yard on Lanett and Beach Eighth,” Uri said slowly. What a nice kiruv moment, I thought, but masked? That’s odd.

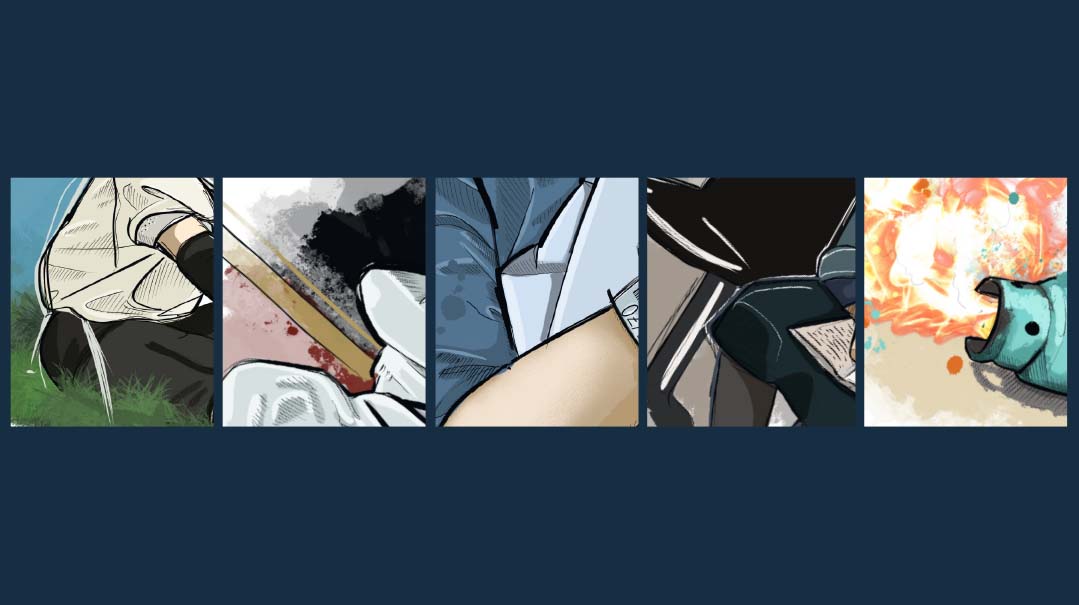

“Efraim Shalom skipped ahead, he was excited to go to shul, and the man pulled out a gun and put it against Eliahu’s chest, asking him for money. Eliahu told him it’s Shabbos, he said he’s not carrying any. He moved his hand so he could take off his watch to give to the guy, but before he could, the guy shot him.”

Wait, what?

It’s cliché, but for a second, time stood still.

Thankfully, Efraim Shalom was ahead of the shooter. He still recalls that he was in his own world, excited about attending Shacharis.

“I saw the man push Abba against the chain link fence,” he remembers. “When I heard shots, I looked around — I thought it was fireworks. Abba crouched, like a baseball catcher’s stance. It looked like he was tying his shoes. He took his hand off his chest and I saw a big red stain.”

A neighbor was walking toward Eliahu from one direction. He blocked my husband from Efraim Shalom’s view, instructed another local who was walking toward him to run to the Agudah of West Lawrence around the corner, and when others arrived, accompanied Efraim Shalom to the yeshivah to find my in-laws.

At the yeshivah, someone got my father-in-law and a Hatzalah member. That member contacted Eli Polatoff, a close friend, neighbor, and Hatzalah member as well.

“Bring oxygen fast!” Eli remembers hearing on the radio.

Meanwhile, the man at the Agudah calmly approached a local medical professional inside and told him what happened. They left the building quickly, and as they raced down the block, Yossi Simha, a family friend, saw them running.

If he’s running, I’m coming too, Yossi thought.

Yossi, a medic who trains emergency medical technicians who work in tough city neighborhoods, is very familiar with gunshot wounds. When he and the medical professional got to Eliahu, he was still sitting up and seemed pretty calm.

Eli arrived with the oxygen, and the three of them lay Eliahu down. Within minutes, he was on a stretcher on the ambulance, with them monitoring his vitals and speaking to him the whole way to the hospital.

I’m proud to say that the same lady that faints at the sight of blood was taking all of this news with aplomb. I remember switching on this gear in my head, telling myself, Chaia, you’ll have a chance to lose it later. Now you need to get a grip.

Uri told me Hatzalah took Eliahu to Jamaica Hospital in Queens, 40 minutes over the Van Wyck Expressway.

“Jamaica?!” I yelped. I was horrified — it’s in an awful neighborhood.

“It’s actually the best trauma center here,” Uri explained. “It’s right near the airport, and people get shot in Jamaica all the time. The local hospitals have less experience.”

Comforting, I suppose.

“Let me just go change out of my snood into a sheitel, otherwise they won’t take me seriously at the hospital,” I told the men, but they advised me to stay home until there was more information.

Suddenly, it hit me — Efraim Shalom!

The men told me someone had taken him into the yeshivah.

“Be right back,” I told them, and I ran down the block through the schoolyard. A patrol car was parked there, and the block was swarming with cops.

“I’m the wife of the guy who got shot,” I said, hoping for information.

“We don’t have a lot to go on,” an officer informed me. “A good Samaritan in the park saw what happened, called 911, and ran away.”

I retrieved Efraim Shalom, and we walked home to wait for instructions. I was careful not to bring up the shooting much; I don’t remember exactly what we spoke about, but there was a lot of, “Hashem is going to take care of Abba, and you’re such a hero that you stayed until help came” kind of talk.

By the time we got back, my house was full of the neighbors I’d invited to join me for coffee, as well as their kids.

“Let’s say Nishmas,” one advised. Another helped me pack a bag for the hospital. I was grateful for the company, because I didn’t want to be alone.

Finally, about an hour later, Uri returned and told me to meet the cops at the crime scene — they would drive me to the hospital.

“They need you to help with making decisions — approving surgery,” he said gravely.

Yikes.

I ran, but when I got there, the officer said they couldn’t spare anyone to drive me because they needed to guard the area. At that point, I was desperate to see Eliahu. I noticed two journalists from the New York Post standing on the side trying to get the scoop.

“Hey, I’m the wife of the man who was shot. If you want the story, drive me to the hospital,” I offered.

They readily agreed.

When we got to Jamaica Hospital, Hatzalah met me in the emergency room. Eliahu was awake, he hadn’t fallen asleep at all, they said, and I went to him. He was hooked up to all sorts of machines and looked very uncomfortable.

“Honey, if you didn’t want to fast tomorrow, you could have asked for a heter. This is really dramatic,” I joked weakly.

The doctors explained that they didn’t know what the bullet had penetrated; there was no exit wound, it was still inside him. They needed to operate to locate the bullet and repair the damage. I gave permission, and within minutes, the nurses whisked Eliahu up to the operating room.

I sat silently for what felt like forever in the waiting room. The Hatzalah men had offered to stay, but ever the “hate-to-be-a-bother” lady, I told them I’d be fine. In hindsight, I was probably in shock. I didn’t want to have to make conversation, and oh-so-practical, I didn’t think I had enough food to share.

Finally, after several hours, I walked to the operating ward to check what was going on. There was a cop in the waiting room.

“I have your husband’s belongings here,” he told me. “I’m waiting to find out what happens to him, to know if we designate this crime as a homicide.”

Ouch — sorry I asked.

I think that’s when it dawned on me that this might be serious, but to this day, I try not to dwell on it. I can talk about what I was doing, where the kids were, how we recovered after, all the details surrounding the shooting, but I still hesitate to talk about the shooting itself. Even writing “he was shot in the chest and almost died” makes me uncomfortable.

A few hours later, the surgeon came out, looking wiped.

“Your husband had a lot of internal damage,” he informed me seriously. “It was a low-caliber bullet, and it didn’t enter his chest and exit his back. Instead it acted like a pinball in his torso, hitting almost every major organ in his body.”

The visual had me wincing.

The surgeon took a deep breath, shaking his head, as I waited anxiously.

Is there permanent damage? Is Eliahu still in danger? Spit it out!

“One of the things it hit is directly connected to the vena cava, the large vein that carries blood from the rest of the body back to the heart,” the surgeon haltingly explained. “I’ll be honest, it doesn’t make sense — even after it was penetrated, the vena cava kept pumping blood.”

He paused.

“Your husband is gonna pull through — I don’t know how.”

I did. Thank You, Hashem.

Eliahu was in an induced coma, and finally, about an hour-and-a-half after surgery, I was able to see him. He looked like he was sleeping peacefully.

“There’s not much you can do now,” the nurses told me. “Do you want to go back home, tell your children their father is okay?”

I didn’t want to leave Eliahu alone, but the hospital was stifling — I had to get out. I remember feeling relieved that the immediate crisis was over but anxious about residual damage and how it would affect his quality of life.

I got a ride back and went straight to my in-laws’ house. My mother-in-law was going through our wedding album, and the kids — Efraim Shalom, five-year-old Shoshana, and two-year-old Chaim — looked pensive.

“Abba is going to be okay,” I said immediately.

I’ll never forget the look of relief on Efraim Shalom’s face.

I didn’t have the bandwidth to process anything, let alone the kids, so I gave them a kiss and told everyone I was going home. I tried eating some tuna and crackers so I wouldn’t be starving on Tishah B’Av, but I couldn’t swallow a thing.

On Sunday, friends kept coming to the hospital so I wouldn’t be alone — the nurses in the ICU were shocked. One friend said that when she came with food — everyone wanted me to eat on Tishah B’Av — the security guard looked at her long skirt and bag of food and said, “Frishman? Third floor.” We kept that place hopping.

Finally, that Friday, Eliahu came home — and what a homecoming! Hatzalah transported him in an ambulance so he could lie down, as sitting was still painful. For the same reason, some friends had bought us a new recliner for him to recuperate.

Eliahu and I had been working at Simcha Day Camp in Far Rockaway that summer, where there was an Erev Shabbos Nachamu concert with singer Shloime Dachs. In the middle of the concert, camp director Rabbi Moshe Zimberg got on the microphone.

“Eliahu is home,” he announced, and the entire camp roared in response.

Sixteen years later, I’m still moved when I remember the way we were cradled by the love of the community, start to finish. I’m actually crying as I type this.

That first Friday night was intense. Eliahu was in post-surgery pain, and psychologically we were all a bit unhinged. It’s not a common occurrence in our circles; Eliahu is the only gunshot wound survivor most — if not all — our friends and family know. There was a lot for us to process, and on that quiet Friday night, all we could think was what just happened?

We’re ever-grateful to the community that helped us get through the next few months. Eliahu couldn’t work and he wasn’t eligible for unemployment. Rabbi Yaakov Bender, principal of Yeshiva Darchei Torah where I’ve been working for 27 years, came one night to visit in the hospital.

“Morah Chaia, I don’t want you and Eliahu to worry about anything but getting better,” Rabbi Bender said as I walked him to the elevator. He made sure we were taken care of until Eliahu got back on his feet.

His son Boruch Ber Bender had not yet founded the community help center Achiezer, but we like to quip that Eliahu’s shooting was an Achiezer test run. Boruch Ber coordinated all the volunteers, arranging for whatever was needed to keep our spirits up.

The entire community just didn’t stop doing, from the moment Shabbos was over, when a neighbor knocked on the door and offered me a ride to the hospital. I know it seems like an obvious favor, but I was touched. And this was just the start of the hundreds — no, thousands — of chassadim people did for our family. They sent so much food, my freezer was stocked with meals until Pesach-time, nearly eight months later! I never had to drive to or from the hospital. Our families basically took over childcare, watching the kids while I was back and forth, and people stayed with Eliahu in the hospital round the clock so I could be with the kids. We felt very loved, and with that came a sense of achrayus. Now what?

Because the doctor didn’t want Eliahu to have stitches on his back at the same time as his front — it’s a tougher recovery — he left the bullet in temporarily. It was finally removed in mid-November, and on a Motzaei Shabbos several weeks later, we held a seudas hoda’ah for about 60 people at the yeshivah.

I remember Eliahu’s quip that his speech would have been easier to write for a seudah a month later, during Chanukah, what with all the miracles we experienced, but it came during the Thanksgiving festival.

Eliahu thanked every individual in attendance, detailing what each one did for us.

“While I was physically shot down, in so many ways, this experience lifted me up,” he said. “It gave me so much chizuk that the community loves and cares for my family. It reminded me to appreciate each day and that Hashem can guide a tiny bullet away from my heart, to avoid permanent damage.”

We gave out a pocket-size Tefillas Haderech, our way of thanking everyone for participating in Eliahu’s road to recovery. And of course, Frishman style, we had some fun with our saga. That Purim, I dressed up as a mugger, Efraim Shalom was a policeman, and Eliahu and the baby were Superman. Maybe Eliahu couldn’t deflect a bullet to the chest, but he sure could get up after being shot down! (Shoshana wanted to be a princess.)

For mishloach manos, we gave out Paskesz L’chayim chocolate bars, a candy watch, a small liquor, along with a mask and a “shot” glass. Yes, we got many groans, but my kids loved that we were finding the humor in what had been a terrifying situation, and therapists we had spoken to advised that it was healthy to show this wasn’t bringing us down.

Sixteen years have passed, and our Shabbos Chazon kiddush hoda’ah is still going strong. Eliahu is a quiet kind of guy, certainly not one to demand an annual party, but he’s insistent about this. There was the kiddush we made three years after the shooting, when I was nine months pregnant with Yosef, our youngest, and the one we made 13 years later, the week before his bar mitzvah. Last year, we had a Covid-conscious outdoor kiddush.

As I said in Nishmas that fateful Shabbos morning, “Ein anachnu maspikim l’hodos l’cha Hashem”— we have unlimited gratitude to Hashem and His shlichim for giving us an opportunity to see His chasadim up close. We’ll never stop expressing it — and with it, the hope that one day, maybe this summer, we’ll host our kiddush when Shabbos Chazon no longer heralds a day of mourning, and as we recount our personal salvation, we’ll rejoice with all of Klal Yisrael, a nation celebrating Tishah B’Av and yeshuos together.

Chaia Frishman is an educator and writer who owns Fruit Platters and More with her husband Eliahu. She lives in Far Rockaway, New York.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Oops! We could not locate your form.