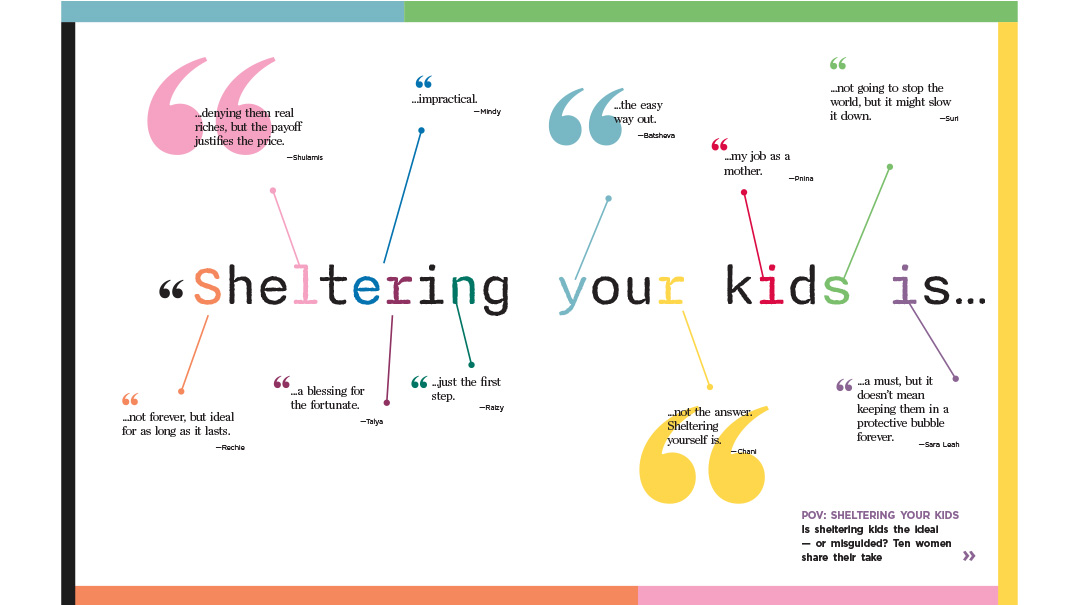

Sheltering Your Kids Is…

| September 29, 2024Is sheltering kids the ideal — or misguided? Ten women share their take

Sheltering your kids is… not forever, but ideal for as long as it lasts.

The world is coming for our kids, but there is no need to hasten its arrival. So much out there is the antithesis of our hashkafos. Feminism, alternative agendas… I know my kids will be exposed to these ideas eventually. But I want them to have a strong and pure bedrock for as long as I can help it. That’s why I make every effort to keep them completely cut off from anything secular, even the news. Hopefully, when these ideas enter their orbit, the kids will be solid enough to filter and reject appropriately.

—Rechie

Sheltering your kids is… a blessing for the fortunate.

During Covid, our teenaged son unsheltered himself from the filtered environment that we, his parents, had carefully constructed. We now live in a fascinating reality: We’re a dumbphone family with filtered computers, no social media, and minimal devices — oh, and also there’s a teenager with open access to screens, devices, and every sort of digital media, living right here in our home.

The first time his shtark brother came home from yeshivah and discovered an unfiltered device in their shared bedroom, he moved out for the night. But how long can you keep that up? It’s your bedroom. More crucially, it’s your brother. Eventually they found a truce — the same uneasy truce that pervades our entire household.

We are so grateful that our son considers this home his haven; we don’t take it for granted. He knows that we’re not thrilled about his devices, but he also knows that we don’t criticize or nag. He tries to do most of his screen-watching in his bedroom, away from the eyes of his little sisters. And we try to save most of our angst for our conversations with Hashem.

But beyond those simplistic ground rules, there’s a lot of complexity. Smartphones, especially the unfiltered types, offer lots of conveniences, which translate into interesting quandaries for us parents. We made the decision to shelter ourselves and our kids. So for example, we don’t have the ability to instantly post or share photos. But… our son made different decisions for himself. Are we still a sheltered family? (Should we ask him to send Bubby a picture of the kids on the roller coaster?)

On a more basic level, every parent wants to be part of their child’s life, to connect on whatever frequency resonates with them. So when your son calls you over to his screen to show you the meme of the day, how do you respond? When he rehashes a great Twitter fight, how do you take it? When he offers to demonstrate what makes “his type of music” so great, what do you say?

To anyone else you can say, “Sorry, I don’t do these things. I made a conscious choice to shut them out.” But when it’s your own child, you never want to convey, “Sorry, kid, I made a conscious choice to shut you out.”

—Talya

Sheltering your kids is… denying them real riches, but the payoff justifies the price.

I’ve noticed two different attitudes among frum Jews who are circumspect about secular culture and education. The first one is, “Bah, it’s all shtusim, who needs it?”

The second sounds more like this: “There is definitely enlightenment in that world, but since it’s so enmeshed with damaging and impure elements, we must be selective in how much access we allow our kids to this culture.”

I grew up in a home that embraced higher education, classical music, science, and history. The first approach of derision and degradation doesn’t only feel “off” to me; it feels dishonest. Sorry, but I’ve been there, and it’s not all shtusim.

Chazal tell us that there is genuine wisdom beyond our boundaries. Having tasted it, I want my children to have it, too. I want them to experience truly quality writing. I want to share the awe-inspiring world of complex classical music with them. I’ve seen that a broad and deep knowledge of history will enrich and inform their learning — knowing the era and challenges of a Rishon or Acharon can heighten our appreciation of their commentary. And I think calculus is next to G-dliness; only an all-knowing Being could create such an elegant mathematical discipline.

But as a parent living in the 21st century, vetting secular books before my kids read them, determining what music is welcome in our home, or trying to temper family political discussions — what can I say? The first approach, the absolute barrier, is a lot less murky to navigate.

Some of the “outside” culture is enriching. A lot of it, though, is coarse and low. Ideally, if you choose to allow some of it in, you will remain constantly on guard, ensuring that your children’s exposure is intentional, thoughtful, and filtered. In real life, it’s much easier said than done.

And while I am very uncomfortable with the “Bah! Shtusim!” approach, seeing the products of those super-insular homes, I can’t deny that the formula works. Maybe not for every child of every parent in every family. But taking in the big-picture view, I’ve seen enough success stories to question my assumptions.

The children who grew up with firm, high barriers may be uninformed and unsophisticated (don’t ask them to name the presidents or state capitals, and definitely don’t ask them about the intersection of world history with Klal Yisrael’s journey toward our destiny). They certainly are not very nuanced. But they are so pure. And don’t we all dream of pure children?

—Shulamis

Sheltering your kids is… impractical.

We strive for normalcy within an abnormal world, and it’s not easy, especially as kids get older. For my family, in my community, that does not mean extreme sheltering. But it does mean firm and clear boundaries, even if my kids’ friends can do certain things that we don’t allow. For example, my kids are prolific readers and read secular books (that I vet first). But they don’t have iPads or iPods, there is no readily accessible computer in our house, and they don’t have access to our (filtered) cell phones. My older kids have 24-six devices, and my boys watch sports with my husband.

Sheltering as a blanket hashkafah is misguided and naive, and it backfires in a glittery 2024 world. I don’t live in a shtetl. While that would eliminate some of the worry and decision-making, it’s not practical for my life and my family. It’s okay for my kids to be exposed to others on different hashkafic levels, as long as they know what our standards are, and why — what our mesorah is, where we come from, and where we’re going. We’re comfortable saying no, and we’re comfortable explaining uncomfortable things. Above all else, I want my children to be safe, and to know that their parents are a nonjudgmental haven for all their questions. I don’t think any realistic parent can be confident that their mehalach will work 100 percent, but we do our hishtadlus, daven hard, and leave the rest to Hashem.

—Mindy

Sheltering your kids is… not the answer. Sheltering yourself is.

I have seen so many parents try to shelter their kids, thinking that it’s stellar chinuch. But they, themselves, are exposed to almost anything. If you want siyata d’Shmaya and children whose hearts and minds are pure, start with your own purity. Strive for high levels of discipline and tzniyus in your own life, and Hashem will help you with your kids. Because we all know, even in the best of places, we cannot control what our kids will see and hear.

—Chani

Sheltering your kids is… not going to stop the world, but it might slow it down.

A decade ago, I would have scoffed at the idea of sheltering my kids. I was going to be honest with my kids, and we would process the world together, with parental guidance. But once I started teaching students who were more exposed, my view became much more rigid.

The world is going to do its best to throw itself at my kids. We don’t live in a controlled environment where I can decide what they see and hear and know. They’re around other kids, living lives outside of my home, and they’re going to witness things that are out of my reach. All I can do is build a wall between them and the world, no matter how flimsy, and try to keep most of it out. That doesn’t mean I’m not going to keep those lines of communication open; I don’t want my kids to be ashamed to talk to me about what they learn. I’d just prefer that we didn’t have those conversations at all yet.

—Suri

Sheltering your kids is… a must, but it doesn’t mean keeping them in a protective bubble forever.

So many people parent in terrified mode. They’re worried that anything can destroy their kids.

It’s not difficult to understand why people think this way. There’s so much out there that could destroy a child’s soul — and everyone wants to be responsible. But children are curious. They hear things and they have questions — even in homes with the highest protective barriers. I’d rather my kids ask me their questions instead of finding answers somewhere else. This doesn’t mean dumping information on kids too young to handle it. But there are teachable moments or reasonable times for questions, when parents should step up and offer an age-appropriate answer.

Sometimes it means telling your kids about tough topics, like alcohol or drug abuse. Some people think avoiding these topics acts as prevention, but this is where sheltering could be dangerous. It’s better to educate kids about these dangers.

These days, people prefer to send their kids to schools where everyone is like them. We didn’t grow up that way. In a mainstream Brooklyn school, my classrooms had many different types of children. We understood that people could be different, and it didn’t make us less loyal to our families’ hashkafos. I wonder why people don’t trust their kids as much anymore.

—Sara Leah

Sheltering your kids is… just the first step.

I don’t understand people who don’t believe in sheltering their kids. Childhood should be a cocoon where you can develop in a safe, healthy way. But sheltering is just the first step. When your child does get exposed to things — as they naturally will, whether hearing inappropriate words or topics from friends, or interacting with a cashier named “Storm” who looks neither male nor female, or overhearing horrific stories about October 7 — that’s when communication starts. Talk about it. Give them context. Help them understand the topic through a Torah lens. We shouldn’t be scared when our child comes home with disturbing information (even if we might internally wince) because it’s a golden opportunity to help them make sense of the world, in real time, on a level they can understand.

—Raizy

Sheltering your kids is… the easy way out.

I recently listened to Mordechai Weinberger, LCSW, discuss exposure therapy for phobias. Of course, he explained, no one would instruct a client who’s afraid of flying to just hop on a trans-Atlantic flight. Properly done, exposure therapy starts off slow, first acclimating the patient to airports, then planes, then planes that are sitting on the tarmac, and only gradually building up to flying, all the while offering reassuring therapeutic support.

We need to frame the discussion not as a choice between “sheltering versus exposing” but as a choice between “sheltering our kids or providing a great deal of supervision and support as they are gradually and safely exposed to the world around us.” Even that phrase isn’t thorough enough. Can we call it “carefully calibrated exposure, entailing deep understanding of their level of maturity, and ongoing honest and nonjudgmental conversations while conveying our deeply held values”?

It’s not for the faint of heart. I know that people consider it hard work to shelter children. You have to screen their reading material, find kosher entertainment venues, and remain constantly vigilant. But to me, the alternative is actually a lot more daunting.

If the alternative were just sending off my kids in the morning and trusting them to make good choices, then it probably wouldn’t be so much work. But the thing is, trusting kids to make good choices actually takes a huge amount of groundwork.

In an ideal world, would I spend more time doing it? I suspect it’s a great investment. There are no walls high enough or impermeable enough to keep the outside world out, so it makes sense to me to keep at least the initial exposure on my terms, and to teach my kids the skills for dealing with ideas that clash with ours.

At the same time, this type of controlled exposure requires great communication and mutual trust. Right now, I’m putting all my energy into inculcating menschlichkeit, yiras Shamayim, and basic human decency in my kids. I daven that once that groundwork is in place, they’ll have the moral strength to face an unfamiliar world.

—Batsheva

Sheltering your kids is… my job as a mother.

With the state of the outside world the way it is nowadays, it seems like a toss-up. And both sides are extreme: Have your children exposed to information that can’t be considered age-appropriate in any shape or form… or keep track of what they read, see, where they go.

A middle way? I don’t see how that’s possible, with the ease and speed in which information bombards us. So yes, many parents would consider our chinuch draconian. No secular books? Reading material censored by parents? No smartphones? One strongly filtered password-protected computer that only parents touch, solely for work purposes? Shocking?

I prefer to be my child’s filter to the outside world.

I know my children. And just as I know their preferences for smooth or grainy textures, for spicy or bland food, brain versus body activities… I know what their comfort or anxiety levels are, I know what their capacity may be for bad news, for ideas that are too big or too small for their minds. I want to choose how, what, where, and when they’re getting their information about life.

Delusional? Yes, I’m aware that my children go to school. I’m aware that there are ads in the street. I’m aware that there will be a neighbor who might say something about a terrorist attack, or sing a song we don’t approve of.

I’m also aware that if I keep my ears open, if I know that I’m the conduit between my children and the world, I’ll hear what they’re thinking. I’ll listen to their questions and answer in a gentle and honest way — respecting my child, his age, and his capacity for understanding.

Chanoch lana’ar al pi darko. And I think for me, for them, this is the best way.

—Pnina

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 913)

Oops! We could not locate your form.