Shelf Life

Mishpacha writers take a trip down memory lane to share the seforim that transport and transform

Project Coordinator: Gitty Edelstein

Your mother's beloved siddur. The Lekach Tov that you spent hours poring over that taught you more than just the parshah. The Sdei Chemed with a special inscription from your rebbi.

Learning is in the DNA of the People of the Book, but these holy texts do more than increase knowledge — they open vistas, build connections, and even change the course of your life. Mishpacha writers take a trip down memory lane to share the seforim that transport and transform

Higher and Higher

Shmuel Botnick

Sefer: HaMesores Hashalem

Takes me back to: Pre-1A and our Chumash party

I’m a Yesodei kid. Not that this means anything to you, but in Toronto in 1998, it was a statement of identity as critical as “I’m a Jew” or maybe even “I’m a human.” Being a Yesodei kid meant you attended Yeshiva Yesodei Hatorah, as opposed to Toronto’s other boys’ elementary schools. It suggested a certain size and material yarmulke, a relatively longer set of peyos, and a lexicon that summarily replaced “actually” with “gradeh.” And perhaps of greatest relevance, under no circumstances could you join any organized sport leagues (read: hockey).

But being a Yesodei kid meant something else as well. Something far deeper, more meaningful, and forever enduring. It meant that for the most impressionable stage in your educational development, you lived in a conceptual Yerushalayim.

You see, the school’s primary patron was the legendary Reb Moshe Reichmann z”l. It was Reb Moshe’s view that Yerushalmis are the most effective teachers of the alef-beis, and he facilitated the hire of two Yerushalmi rebbeim, Rabbi Mordechai Paksher and Rabbi Ahron Cohen, to serve as the school’s Pre-1A rebbeim.

I was introduced for the very first time to the chein of Yerushalayim in Rabbi Paksher’s class. Ah, is there any word to describe that chein? Exaltedness? Sublimity? Holiness?

Sweet. That’s close. Yerushalayim is a sweet place, a zeese platz, and those born and raised within its sacred borders are sweet people, zeese menschen.

Our beloved rebbi sported a rekel the likes of which we had never seen, and had neat, tightly curled peyos pressed before his ears as he taught with a sweetness that was absorbed into our young hearts.

Understandably, the alef-beis textbook assigned to us was Yerushalmi as well. Compiled by one Rabbi Moshe Chaim Cheshin, a melamed in Yerushalayim’s famed Eitz Chaim yeshivah, its bright orange front cover is framed by nekudos lacing the border. In the center are two luchos with a tree on each side, and at the foot of each tree is a dove with a sefer Hamesores in its mouth. An explanation for this illustration sits in an arc shape at the bottom: “Knesses Yisrael l’yonah imsila — the Jewish People are analogous to a dove,” a quote from Sanhedrin. The cover also testifies that this is the product of shanim rabos [many years] of hard work, and while the sefer doesn’t have an initial publication date, letters of approbation extend back to 1956.

For the lion’s share of the school year, our class of five-year-old boys learned the sacred letters of the alef-beis from this sefer daily, in a distinctly Yerushalmi accent. Our tongues rolled back to eject the lamed and our chiriks came out with a very pronounced “ee.” When we would break for recess, we’d play soccer until the cry came, “Arrrein!” — the “r” rolling from the back of Rebbi’s throat. Then it was back to the classroom, back to the Mesores.

T

he Mesores was, for lack of a more professional term, delicious. There was no glossiness to the paper — it wrinkled if you turned the pages too quickly — so a dose of caution was in order.

The opening page displayed the alef-beis in order, each letter in its own orange box, but subsequent pages got trickier. The order became scrambled, hei inexplicably aligned with tes, beis with yud, and it got trickier yet as you faced shins and sins, tufs and sufs. Reishes and daleds looked awfully similar, samechs and ender mems nearly indistinguishable — and the onus was on you to tell the difference.

Each page had a different color scheme, often with an ornamented border. From time to time, there would be a notation (he’arah) at the bottom, in Hebrew of course, alerting us to the fact that there are various permutations of the shva, for example.

We celebrated our completion of the Mesores with a Chumash party, marking our transition from learning alef-beis to learning Chumash. Every Yesodei kid, no matter where life has taken him, remembers that Chumash party.

We practiced for weeks, learning Yiddish song after Yiddish song, and memorizing the staged conversation between the rebbeim and talmidim, also in Yiddish.

The event was held in the Bais Yaakov High School auditorium. Adorned in crowns of metallic bristol board with a sash of the same material inscribed, “Ben chamesh l’mikrah,” each child walked onto the stage independently, holding a candle, while the ancient Yiddish tune “Oyfn Pripetshik” played in the background.

Then, with Rabbis Cohen and Paksher conducting the presentation, we would sing and clap.

Tateh ich dankt dir

Tateh ich loib dir

Az ich bin a yid

Father, I thank you, Father, I praise you, for I am a Jew.

Rabbi Paksher would turn to us and, in a singsong, lead the dialogue.

“Yingerlach, yingerlach vuhs lernst du?” (Children, children, what are you learning?)

“Mir zenen nisht yingerlach! Mir zenen bochurim!” (We are not children! We are bochurim!)

“Bochurim, bochurim, vuhs lernst du?” (Bochurim, bochurim, what are you learning?)

“Chumash!”

“Chumash? Vuhs meint Chumash?” (Chumash? What does Chumash mean?)

“Finef!” (Five!)

“Finef vuhs? Finef lollipops?”

“Nein!”

“Finef cookies?”

“Nein! Finef chumashim in dem heilegen Torah!”

Purists will recognize that the Yiddish itself carried a Yerushalmi dialect — “der” turned to “dem,” “heilige” to “heiligen.”

We opened our Chumashim to Vayikra, in accordance with the age-old minhag cited in Midrash Rabbah, which teaches, “yavo tehorim v’yisasku b’taharos — let the pure ones come and toil in purities.” In responsive chanting with our rebbi, we read the first few pesukim:

Vayikra — uhn her hut gerufen

El Moshe — tzu Moshe Rabbeinu

Veyidaber — uhn her hut geredt….

We completed the segment, and then a dialogue with Rabbi Cohen ensued.

“Teihere kinder vuhs ligt in dem vort Vayikra?” (Precious children, what lies in the word Vayikra?)

“A kleinem alef!” we’d respond.

“Farvuhs iz duh a kleinem alef?” (Why is there a small alef?)

And in Yiddish, we’d explain: Moshe Rabbeinu “hut zich gehalten klein — held himself small,” undeserving of Hashem’s personal summons, and he preferred to write “Vayikar,” connoting a less formal encounter, rather than the honorable “Vayikra.” Ultimately, he consented to writing “Vayikra” but only with a “kleinem alef.”

I’ll take the liberty to posit that nowhere else in North America does such a patently Yerushalmi experience transpire.

On a visit to Toronto a few years ago, my then-five-year-old son Aharon emerged from my parents’ basement, Mesores in hand (I don’t know if it was mine or my brother’s). He was excited about his discovery — it had the alef-beis in it! — and he opened the sefer and began reciting the letters. Aharon did well, trying his best to navigate through Rav Cheshin’s well laid traps.

Yingele yingele, vuhs lernst du?

You don’t know Yiddish, Aharon, but if you did, you’d know to say, “Ich bin nisht a yingele, ich bin a bochur’l!”

It’s cute to think of yourself as a bochur’l, Aharon, but you are a yingele, just as we were, and that’s something to be proud of. You’re a kleinem alef; hold yourself small even as you grow big. Small is safer, sweeter, purer.

Aharon, in your hand you hold a relic of Yerushalayim, a zeese platz, written by an old-time Yerushalmi melamed, a zeese mensch. Feel Yerushalayim, Aharon, feel its purity and its sweetness; even from afar you can be among the yeladim v’yelados misachakim birchovosehah.

And to all the Yesodei kids out there, my fellow kleinem alefs, here’s a humble suggestion: The next time you’re in your childhood home, go down to the basement and check out the boxes of old seforim. If you’re lucky, HaMesores Hashalem will still be there. Take it, lock yourself in a room, and sing and clap and celebrate with the spark that was ignited so many years ago.

Tateh ich dankt dir

Tateh ich loib dir

Az ich bin a yid

Molded by sacred letters, encased in a depiction of luchos, trees, doves, and a testament to shanim rabos of labor, let that sweet innocence live on.

Shmuel Botnick is a contributing editor to Mishpacha Magazine.

Point of Pride

Meir Raab, as told to Esty Heller

Sefer: Sdei Chemed by Rabbi Chaim Chezkiah Medini

Takes me back to: Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin in Bnei Brak, 1976

I grew up in Bnei Brak on my mother’s famous mohn cake and my father’s diet of Gemara. We lived in a tiny, two-bedroom apartment. We ate fleishigs only twice a week. I never got new clothing. And yet I never felt a lack. We had cheder. We had family. We were privileged.

One of the greatest privileges in my life was the opportunity to learn in Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin in Bnei Brak under Rav Shmuel HaLevi Wosner ztz”l.

I was 12 years old when I entered the yeshivah. I felt small and invisible mounting the stairs of the tremendous building, but from the minute I sat in shiur, I was drawn to the Rosh Yeshivah, to his sharp mind and warm heart.

In Lublin, I quickly learned, everything had a zeman and everything had a seder. At five every morning, all bochurim would be sitting and learning in the beis medrash, and we learned until ten p.m., with breaks for meals and a short nap in the afternoon. There was no fooling around. If you were there, you were there to learn. (The intense yeshivah schedule wired my circadian rhythm, and until today, I’m a very early riser.)

The Rosh Yeshivah was involved and invested in every part of the seder hayom. Every morning before Shacharis, he would recite Kaddish d’Rabbanan, after which he would appoint a bochur to daven before the amud. I was terribly shy, so I made it a habit to slink away outside right after Kaddish to avoid being picked. One day, though, the Rosh Yeshivah quietly followed me outside.

“You’ll lead the davening for us today, Meir,” he declared with a triumphant smile. He ushered me inside, and I had no choice but to make my way up to the amud.

After davening, with all of us still wearing our tefillin, the Rosh Yeshivah would leren fohr a shiur of Orach Chaim before dismissing us for breakfast. Every minute in yeshivah was utilized to its fullest, and in his effort to maximize the learning time, the Rosh Yeshivah made sure to keep up with all the goings-on in yeshivah. Friday night after the seudah, when the bochurim were itching to go to various rebbes’ tishen, he would sit with all of us and lead a butteh, his special farbrengen, thereby ensuring that we put in adequate learning time before heading out.

We had absolute yirah and derech eretz for our Rosh Yeshivah, who ruled with unquestionable authority, but he also served as a warm, loving father figure, taking sincere interest in each boy’s learning and wellbeing.

The Rosh Yeshivah had a daily custom of taking an early morning walk, often when it was still dark outside. Since the Gemara says a talmid chacham should not be in the street alone at night, he chose a different bochur to accompany him each morning. The Rosh Yeshivah used the occasion to inquire about us — how are things in the family? How’s the learning going? — and we bochurim reveled in this experience; it was a sacred time for us. The dark, quiet, and airless Bnei Brak streets offered a relaxing setting, allowing us to establish strong personal ties with the Rosh Yeshivah.

One morning, when it was my turn to walk with the Rosh Yeshivah, he asked how I was doing with my learning. I shared that I’d been learning an extra seder, Seder Moed, on the side of the regular yeshivah seder.

“Why do you learn it?” he asked.

“I found I had extra time during seder, so I figured I’d squeeze this in,” I responded.

The Rosh Yeshivah wasn’t at all impressed.

“The yeshivah determines what the bochurim should learn, so I’m not happy about this,” he admonished me. “But… if you finish learning Seder Moed and come in for a farher, I’ll consider this limud a seder from yeshivah.”

I agreed, and I got three other bochurim to join me in learning this additional seder. All of us passed the farher, and the Rosh Yeshivah beamed with pride.

At our Purim Seudah shortly thereafter, he called the three of us over.

“I want each of you to choose a sefer you wish to own. This will be my gift for your great hasmadah.”

I chose Sdei Chemed, and the Rosh Yeshivah personally inscribed the first volume.

The nondescript-looking ten-volume set of seforim, black leather with silver stamping, has its place of honor in my seforim shrank all these years. I’m not happy about this, the Rosh Yeshivah originally told me, but my cherished Sdei Chemed attests to the truth: I’d made the Rosh Yeshivah happy. I’d made him proud.

Meir Raab was a close talmid of Rav Shmuel HaLevi Wosner ztz”l from his yeshivah days in Bnei Brak.

Week by Week

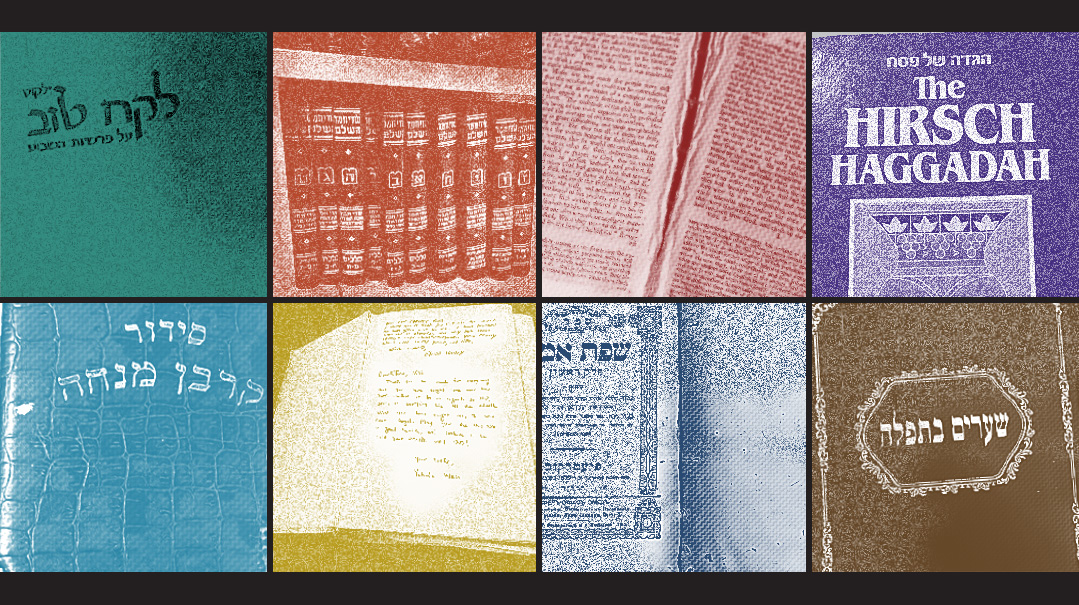

Sefer: Lekach Tov al Parshas HaShavua

Takes me back to: The Kosel, during my seminary year

It’s an unpretentious set of slim brown books sitting in a remote corner of the seforim shelves, away from the premium shelf space hosting more prestigious volumes. But when I open the front cover of Shemos and see my name scrawled in thick black ink, I remember my weekly chavrusa at the Kosel, and as I turn the pages and read the faint penciled translations and explanations abutting the Hebrew text, I’m reminded of that year of discovery.

Even 30 years ago, seminary was less a choice and more a rite of passage for your average day school graduate. Objectives were a mixed bag: some came for the Israel experience, to gain independence, or make new friends, while many of us had a vague notion of loftier goals like growth and learning. But in those pre-ArtScroll Revolution days, when most seforim were available only in their native Hebrew, fluent reading and translation was a serious prerequisite to independent study.

It’s not that I wasn’t capable of reading and translating Hebrew — I’d been in the yeshivah system for 12 years — but my lack of fluency in the language (certainly in the non-Biblical version favored by more current classics) and my quasi-phobia of large blocks of Hebrew print (particularly in Rashi script) were significant impediments. Nonetheless, when my ambitious sem-mate suggested we have a Thursday night parshah sefer chavrusa, I hid my reservations and merrily agreed.

I don’t remember whose idea it was to learn Sefer Lekach Tov, but it was a perceptive choice, hitting the sweet spot for language, concepts, take-home lessons, and an unintimidating block Hebrew font. Each parshah offered shorter and longer pieces, giving latitude to study multiple ideas in one sitting. Classic seminary girls, we were determined to make this an epic weekly event, and we decided to learn in the shadow of the Kotel and round out the evening with dinner.

Thus commenced one of the most gratifying parts of my seminary year. The weather cycled predictably along with the parshiyos: the cool, breezy evenings that characterized the first half of Bereishis intensified to blustery coat weather by the time we hit Shemos. But we forged on, struggling to turn pages with thickly gloved fingers, balancing an umbrella beneath the drizzle, and eventually retreating to the congested stone room adjacent to the Wall where we sat hunched among murmuring women, inhaling the scent of puddled wax from dozens of dripping candles bordering the space.

When we encountered a word or phrase foreign to our American tongues, we’d search for context clues or whip out our trusty dictionary, and resolved uncertainties were carefully penciled into the sefer’s pages. It was interesting to note that our inquiries repeated themselves, and I’d wonder about the conjugation of the same verb I’d struggled with the previous week, or a colloquialism I hadn’t quite mastered.

But as my Vayikra volume replaced Shemos and was later switched out for Bamidbar, I had an epiphany: I was getting better at this. Not fireworks amateur-to-pro style, but rather in gentle, measured increments of growth — like the first time I recognized a conjugated form of “hesaig,” a word that had confounded me.

Over the year, I learned to unknot a thorny phrase and to discern between popular Aramaic idioms and words I’d likely find in my Hebrew-English dictionary. Most importantly, I overcame my reflexive fear of text. And the small pencil markings, marching along the pages I’d studied like a trail of industrious ants, marked my achievements for posterity.

Posterity, indeed. Because now, decades later, when I mentor my self-doubting seminary students and tell them of my initial hesitant foray into the deep and broad world of seforim, they frown, disbelieving.

“You, Mrs. Moskowitz? You were totally the type who came to seminary able to open any sefer without a problem!”

I chuckle, and I tell them the story of the Sefer Lekach Tov.

Elana Moskowitz had been teaching in seminaries for over 20 years and is a regular contributor to Mishpacha. She lives in Yerushalayim with her family.

From the Heart

Rabbi Paysach Krohn, as told to Gitty Edelstein

Sefer: A set of Rambam Yad Hachazakah

Takes me back to: My childhood home in Kew Gardens, New York

MY family moved to the Kew Gardens neighborhood in Queens, New York, when I was seven years old because my father was a mohel and there were already many mohelim in Brooklyn. I attended Yeshiva Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn for yeshivah and mesivta. Unlike many students my age, I didn’t dorm — the dorm was for out-of-towners or local boys who wanted to sleep close by after night seder — but my father, a talmid chacham in his own right, was my night seder chavrusa.

The first masechta we finished was Taanis, when I was in 11th grade. I loved that masechta, and since the boys in my Pirchei group were starting to learn Gemara, I proposed to them that we learn it together. They were willing to give it a try, so we started a weekly seder; it took us over a year to finish. We made the siyum in the spring of 1963.

The rav of our shul, Rabbi Yaakov Teitelbaum, was proud of our Pirchei group, and he hosted the siyum during the shul Shalosh Seudos one week. My father was also incredibly proud, and he told me that he, too, wanted to make a seudah for us.

It was a sunny spring day and my parents set up a table outside where they served salami sandwiches and hot dogs with ketchup (who could afford a barbeque back then?).

At the end of the meal, one of the boys from the group got up and thanked me on everyone’s behalf. I was moved by his short speech, an emotion that morphed into shock as he pulled out a large Rambam set. I wasn’t expecting a gift — I was grateful enough for the party — and I excitedly thanked the boys as they crowded around to show me their signatures inside the front cover of the first cheilek.

Then I noticed an inscription nestled among the juvenile scrawls: I also share in this matanah, a token of appreciation for your serving as an inspiration not only to your talmidim but also to your brothers and sisters. It was signed, “Avicha ohavcha — your father who loves you.”

Until that moment, I didn’t realize that the present wasn’t from the boys, but from my father. In hindsight it makes sense — while sets like this are more common now, they cost a fortune at the time, too much for families of modest means to gift a teenager.

My father wasn’t wealthy, but he wanted to demonstrate how proud the past year made him. He wasn’t an outwardly sentimental person. He didn’t make a big speech at the seudah, and he was content to sit and watch the boys give me his gift. For him to write something like that was striking, and it was in that moment that I realized how much the yearlong seder and the siyum moved him.

If this story took place today, I would have been crying. But I was a teenage boy, so I just walked around the table and kissed him.

The inscription from my father took on a deeper meaning when, three years later, he tragically passed away at a young age. Even decades later, that inscription reminds me of his love and brings me solace.

Rabbi Paysach Krohn is a renowned lecturer, author, and mohel.

Rhyme and Reason

Dov Fuchs

Sefer: Horeb, by Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch ztz”l

Takes me back to: Highway 1 to Yerushalayim

WEwere a group of young rebbeim teaching in a yeshivah that catered to boys from more modern backgrounds, and every day was both an opportunity and a challenge. After seder, many of us who lived in the same neighborhood would carpool back home. One evening, we had a heated discussion about what, and if, curriculum changes should be implemented to help us better connect with the boys.

“We should add some pizzaz to our shiurim,” one rebbi suggested adamantly. “They boys need excitement — they call it ‘edu-tainment’ — and they’ll love it!”

Others felt strongly that pure, unfiltered Torah and its eternal truth is what brings boys closer, no bells or whistles required. (“You don’t need to dilute Torah or repackage it. It works its magic on its own!”)

I saw the merits of both sides, but I had noticed that many of our talmidim were disconnected from the mitzvos, unable to relate to what they were doing, and, even more, why they were doing it.

“We take mitzvah observance for granted, doing what we’re told, regardless of understanding the ‘why,’ ” I said slowly as I formulated my thoughts. “But our boys were raised differently, they need a little introduction to taamei hamitzvos (the reason behind the mitzvos) — maybe that’s a topic for a shiur? Learning Sefer Hachinuch?”

Some nods around the van, some frowns — and one comment from Rabbi Daniel Engel: “Why don’t you teach them Horeb?”

“Reb Who?”

I had no idea who or what he was talking about.

“Horeb!” he replied. “Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch’s sefer on the mitzvos.”

I had never heard of it before, and he promised to bring his copy the next day.

I opened the sefer, and I couldn’t put it down. I was captivated by its brilliance and profundity and the poignant ideas Rav Hirsch brings to light. It wasn’t only the meaning he gave to the mitzvos that stirred my soul; his words were captivating. Horeb opened my eyes to understand Torah in a new way, a new dimension, but it also offered me a deeper understanding of the human mind, heart, and nature. Every line is a masterpiece, and Rav Hirsch uncovers the hidden secrets of every letter and every word. With his panoramic grasp of the Torah, from halachah to Kabbalah, he illuminates the intricate chain of unity that binds them together.

I immediately began learning Horeb with some of my students, focusing on the meaning of the mitzvos and also offering them a glimpse into the meaning of life itself. They felt, as I, that Rav Hirsch’s words were meant for them, as if he knew their challenges and offered sage guidance and direction. For example, every teen struggles with choosing the right friends and the proper outlets. Rav Hirsch addresses both issues: “While your home and school wield great influence on you, the greatest influence is exerted by your social interactions, what you see others do, you feel yourself also capable of doing, raising in you the question whether you would like to act in the same way. And what you seek to be in your thoughts you will easily become in reality before you are aware of it.”

And regarding suitable outlets he writes: “Recreation belongs to the duties which you owe your mental and physical powers. But let recreation be useful to your body, your mind and your spirit. …To read, hear, and speak of anything that does not promote your real life; that flatters the beast in you, that pollutes your imagination and degrades that which is holy… is killing the better self in you….”

How prescient, how poignant, how passionate!

A few months later, when my boys ordered a Horeb for me from America (I had been using Rabbi Engel’s the whole time), I knew that the sefer had made an impact. To this day, though the pages have seen better days and the binding desperately needs repair, I still use that copy.

And since then, I’ve become addicted to Rav Hirsch’s writings. I always say that so many people travel to Europe to visit the kevarim of famous tzaddikim. If there is one grave I would like to visit, it would be the kever of Rav Hirsch.

I’d like to say, “Thank you.”

Dov Fuchs is a writer and rebbi in yeshivos and seminaries in Eretz Yisrael.

True Connection

Rabbi Ilan Feldman, as told to his daughter Russy Tendler

Sefer: Sfas Emes

Takes me back to: Rav Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman’s study in Baltimore, Maryland

I sat in my home office one recent Shabbos morning, gathering ideas for my derashah in shul after Shacharis. I wanted to share a thought about kiddush Hashem, and I knew the general outline, but I didn’t yet have an angle to give the congregants a way of relating to a mitzvah with which they’re already so familiar.

I pulled out a copy of the Sfas Emes, trusting that, as usual, I would find what I needed. Noticing the newer edition I’d taken down, I quickly placed it back on the shelf and reached instead for the copy that signifies for me an eternal and authentic relationship to the words within. As I flipped through its brittle and yellowing pages, I couldn’t help but think, as I often do, of the day I acquired this early edition of the Sfas Emes.

ITwas the summer of 1984, and we were in Baltimore visiting my wife’s family. I sat in the home study of my wife’s grandfather, Rav Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman, rosh yeshivah of Ner Yisroel Rabbinical College. Across from me sat the Rosh Yeshivah, surrounded by floor-to-ceiling, wall-to-wall shelving, every inch of every shelf packed with seforim.

“How are things going?” he asked me in Yiddish, referring to my recent appointment to assistant rabbi in my father’s shul in Atlanta, Georgia.

“Fine,” I responded, thinking about my adjustment to my role in leadership and the rabbinate.

“And your derashos?” Rav Ruderman continued.

“They are going well,” I responded.

“Do you use the Ksav Sofer?” he asked.

I wasn’t very familiar with the Ksav Sofer, and I told him as much.

“So let me give you a Ksav Sofer,” Rav Ruderman said, standing as he spoke.

He went over to his seforim shrank, which seemed to contain almost every sefer in the world.

I’m really just a little kid, I remember thinking to myself. Here is an elderly talmid chacham, the rosh yeshivah, making sure I know he cares.

Though by that point in his life Rav Ruderman could barely see anymore, he knew where each sefer was located on his shelves — and even more so, what each sefer said. He reached up, pulled down a sefer, and handed it to me. I looked at it and realized Rav Ruderman must have been an inch or two off in his estimation.

“Zeidy, dus iz du Sfas Emes,” I told him. “This is the Sfas Emes!”

“Dis zoiche gut, this is also good,” he responded with a nod.

Zeidy’s Sfas Emes was the original print, from 1905. Written by the Gerrer Rebbe, Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter, the Sfas Emes is his innovative exposition on Chumash and Yamim Tovim in which he weaves together pesukim, Gemara, and chassidus to bring out important messages, all thoughts he’d at shared at his weekly tish. Its pages were delicate and thinning and some were completely loose — the binding was already deteriorating — but they were in the right order, and I carefully packed the sefer to take home with me.

I began to study the Sfas Emes, but I quickly recognized that I didn’t understand a word of it properly. This wasn’t surprising — I grew up litvish and attended a litvish yeshivah (Ner Yisrael), so I had never been exposed to chassidish thought like this — but I continued to pour over the Sfas Emes for weeks until I finally felt I could begin to appreciate what he was trying to say. I saw that the Gerrer Rebbe was a master at seeing fascinating patterns of themes that ran through the entire Torah, themes that underline its unity and the fingerprints of its Author.

In the decades since then, I’ve used the sefer to prepare countless derashos and shiurim. Every time I share a thought from the Sfas Emes, I feel connected to both my rosh yeshivah grandfather-in-law, whose interest felt like an endorsement of the highest caliber, and to a profound chassidic leader from the turn of the century, who undoubtedly influenced my Polish ancestors.

I own the modern print of the Sfas Emes, but the newer sefer, its pages fresh and white and intact, doesn’t feel authentic. I still cherish Rav Ruderman’s copy of the Sfas Emes and the memory it kindles. Though its yellowing pages are literally cracking from my touch, this sefer, the one that intertwines two gedolim who represent two immensely different worlds, is the one I treasure.

Rabbi Ilan Feldman has been the senior rav of Beth Jacob Atlanta in Atlanta, Georgia, for more than 30 years.

Decades in the Making

Miriam Margo

Sefer: She’arim B’tefillah by Rav Shimshon Pincus

Takes me back to: Seminary in Eretz Yisrael, 2001

AT

some point during my seminary year, I was appointed head of a shabbaton. I have absolutely no recollection of anything related to that Shabbos. The only reason I remember it at all was because the seminary gifted me a sefer, which I still have, and I wrote inside the cover: Given to me by the seminary as a gift for heading Shabbos Zichron Yaakov, 5762. Began learning this sefer in preparation for a tiyul to kivrei tzaddikim in Tzfas, continued after seminary.

That part I do remember. I met a special friend in seminary. Her name is Rachel, and while she wasn’t the seminary-BFF every girl hopes to make (I had that, too, and have completely lost touch with her), she was a wonderful, close, and thoughtful friend. I’m deeply emotional (like every good seminary girl), but I have a strong cerebral side that also needs food and water, and Rachel is like that, too. Together, we learned the sefer I had been gifted: Rav Shimshon Pincus’s She’arim B’tefillah. A slim, brown volume with gold lettering, like every other sefer I’ve ever seen; a gateway to another dimension.

I kept up with Rachel for a few years after seminary. I was the first contact on her shidduch résumé, and I got calls about her every week. Shidduchim were slower for me, but eventually I got married, too. And then… I hate to admit it… we lost touch.

Not right away. But it just happened. Life was so busy. I worked out of the house ten hours a day, I was newly married, I had a baby, the baby had colic, I had another baby, Rachel had a baby, I had another baby….

It wasn’t only our friendship that fell by the wayside — all forms of formal spiritual learning vanished from my life. My husband said divrei Torah on Shabbos; sometimes I was at the table to hear them and sometimes I wasn’t. When I think back to those years, there’s a foggy film over everything; being a wife and mother of several young children was so all-encompassing, so exhausting, that it overwhelmed everything and left no room for anything else. I missed having friends, and I missed learning, and sometimes I felt like someone had outsourced my spirituality to my husband when I hadn’t been looking and the cerebral part of my personality was withering to death, but every moment of every day and night was accounted for and there was simply no room for any of it, ever.

Last year, I got a phone call from Rachel.

“How are you?” she said, nimbly skipping over the 20-year gap in our relationship. “I want to learn something, and you were my chavrusa, so I called you.”

It was the right time. I jumped at the chance.

We decided to learn Chovos Halevavos, and we’re making our way through it slowly but steadily in weekly phone sessions. I’m not exaggerating when I say that learning has transformed my life. It’s like my brain is on again. I know all these past years were not spirituality-free; every hectic, blurry moment was avodas Hashem in its purest, simplest form. But I missed learning, and I’m so happy the opportunity has come round again.

I keep my Chovos Halevavos on a small bookshelf near the velvet bench on the upstairs landing. It’s where I keep my siddur and say brachos every morning.

And I keep one more sefer on that small shelf: the slim, brown volume of She’arim B’tefillah, the sefer that has brought me full circle and opened His gates for me once again.

Miriam Margo is a writer in Lakewood, New Jersey.

Goldmine

Rabbi Akiva Fox

Sefer: Haderash V’ha’iyun

Takes me back to: High school in Bayonne, New Jersey

When I was a teenager, new yeshivos were sprouting all over New Jersey. The hanhalos seemed to follow a certain pattern: rent the vacant shul, school, or Jewish Community Center in a dying Jewish community for a nominal fee, and with some Sheetrock and stucco, transform the building into a dormitory and beis medrash. I spent two years in such a high school, the Yeshiva Gedolah of Bayonne, which has since blossomed into a bastion of Torah.

Every so often, a handful of old men who still lived in Bayonne would come down to the small, inconspicuous building on Avenue C that housed the yeshivah. There was Sidney Shulman, a staunch Israel supporter, who would raise his voice when reading the haftarah brachos, emphasizing, “Tzion, hi beis chayeinu!” There was a baal korei whose name I can’t recall who sang zemiros with us, including his favorite, “Shabbos Hayom LaHashem.” And then there was Mr. Goldman z”l (I don’t know his first name) who came quite often, davened with fervor, and stayed for the kiddush.

One Shabbos, after the kiddush, Mr. Goldman was schmoozing with us, sharing recollections of his childhood in Europe and reflecting on the world that had gone up in flames. He spoke of Harav Aharon Lewin (Levine) ztz”l, Hy”d, the Reisha Rav, one of the prewar gedolim. He was a brilliant gaon with encyclopedic Torah knowledge who traveled throughout Europe to tend to his brethren’s needs, advocating for them and guiding them in halachah and hashkafah. A masterful orator, the Reisha Rav often represented the Jewish people in the Polish Sejm (Senate).

Tears streamed down Mr. Goldman’s face as he spoke of his beloved rav; he kept choking up, unable to continue. Though decades had passed, he never stopped mourning the gadol of his youth.

“The Reisha Rav wrote many seforim, but one set, Haderash V’ha’iyun is a masterpiece,” Mr. Goldman reminisced, describing it as a compilation of brilliant thoughts on the weekly parshah spanning the spectrum of halachah, lomdus, and drash. “He had a ‘goldeneh pen’.”

I was unfamiliar with the term, but I didn’t ask for a definition.

“Go out and buy the set,” Mr. Goldman prodded. “I’ll pay for half.”

“Why not just pay for the whole thing?” I kibitzed. “I want you to get some of the sechar.”

That summer, I joined Camp Adas Yereim’s learning program in the Catskill Mountains. One afternoon, I noticed the head learning rebbi, Rabbi Falk, holding an old black sefer with yellowed pages. I took a closer look at the name stamped on the cover: Haderash V’ha’iyun.

“Can I borrow that?” I asked him excitedly.

Rabbi Falk graciously agreed, and he shared some information about the mechaber.

“Rav Lewin was a great tzaddik,” he said. “He had a goldeneh pen.”

The exact words Mr. Goldman used to describe the sefer! I thought.

This time, though, I asked for an explanation. Rabbi Falk was happy to provide one, telling me that Rav Lewin had a special way with words and he would formulate esoteric thoughts with masterful clarity and even poetic prose.

“He actually wrote much of the set while traveling by train throughout Europe,” Rabbi Falk said. “He didn’t have seforim with him, and the train’s racket wasn’t optimal for concentration, but his goldeneh pen flowed freely. The set is a work of art.”

I took the sefer to the staff beis medrash and began paging through it. The depth, the richness of the words, the mechaber’s style, and the panoramic breadth of Torah sources were incredible. I became enamored as I read on, experiencing that goldeneh pen. The mechaber opened my eyes in his analysis of every word and yesod, offering clear and beautiful explanations to the most perplexing questions.

At some point, I had to return it to Rabbi Falk, but I was hooked. I hoped that upon my return to the city I would find the set in seforim stores, but apparently Haderash V’ha’iyun had been out of print for more than 50 years. Most people had never heard of it, and those who did didn’t know where to obtain a copy. For months, I asked around and looked through catalogues, but without success.

A year later, I joined the beis medrash in Rabbi Jacob Joseph School in Edison, New Jersey. I had lost contact with Mr. Goldman, and I wondered if I’d ever come across Haderash V’ha’iyun again.

And then one Shabbos afternoon, while looking through Edison’s otzar haseforim, I came across an old set of Haderash V’ha’iyun. I spent the rest of that afternoon oblivious to the world, immersed in the sweet oasis of Torah. The sefer quickly became my weekly Shabbos treat, my menuchas hanefesh. Each vort enlightened — the sefer is a fascinating glimpse into the world of Torah that a gadol sees veiled within the parshah, and for the first time in my life, I found I could “sit over a sefer,” soaking in the geshmak! It infused me with a deep appreciation for learning, training me in how to think and proffer my own Torah thoughts.

After a few years, I went to learn in Eretz Yisrael, where I no longer had access to my favorite sefer. I spent countless hours in Meah Shearim’s old seforim shops, patiently rummaging through boxes of old tomes, but I never found the set I sought. (I even met and befriended a grandson of Rav Lewin in yeshivah, and while I enjoyed singing the sefer’s praises to an appreciative audience, he wasn’t able to help me get a copy.)

One bein hazmanim I was in New York, lost somewhere in Boro Park. I came across a small seforim store on a corner and decided to try my luck.

“No one carries it anymore,” the old chassidish proprietor said. “Maybe I have one volume on my sheimos shelf?”

I knelt down to check — and there, under a pile of dusty seforim and old tzitzis, lay one volume of Haderash V’ha’iyun. The cover was cracked, hanging on by a thread, but the print was clear and crisp. Incredibly, it was Vayikra — that week’s parshah! I was ecstatic.

“Take it,” said the old Yid, but I insisted on paying for it; such a treasure, such a find, couldn’t come for free.

I could barely contain my excitement, and I invited some friends to Chap A Nosh for an impromptu “kiddush.” They were happy to join, of course. As we sat, I attempted to convey what was so exciting about my find, but I don’t think they truly understood my simchah, what it meant to me to finally have a copy of this cherished sefer to call my own.

A few years later, a dear friend arranged to have the five-volume set reprinted for me as wedding present, a priceless gift for which I am forever grateful. But my deepest gratitude is for Mr. Goldman z”l, who took the time with a young yeshivah bochur to lovingly share a piece of his past — one that so deeply impacted my future.

Rabbi Akiva Fox is a rebbi and writer. He teaches in yeshivos and seminaries in Eretz Yisrael.

Guest of Honor

Yosef Herz

Sefer: The Hirsch Haggadah

Takes me back to: Pesach 5780

IT was Leil Pesach of 2020, just four weeks after coronavirus had sent the world into a tailspin. The ominous warnings from doctors and rabbanim made it clear that everyone was to stay put that Yom Tov, upending our plans to stick to the script (first days by my parents, second by hers, both houses filled to the brim with a gaggle of siblings and growing families). There we were, in our Lakewood basement apartment, the babies fast asleep in their bedroom down the hallway.

Our small table boasted a combination of borrowed Pesach dishes, a hastily purchased ke’arah, and whatever wine came in the Beth Medrash Govoha Pesach box. It was a surreal experience, and my wife and I approached our Seder table gingerly.

Suddenly, a guest appeared. He posed no health risk, so we welcomed him — and it became abundantly clear this was no regular guest. His regal bearing and disposition bespoke solemnity and penetrating depth, engendering an atmosphere of reverential awe. Our guest didn’t speak at random — he was composed and calculated — but when he did share his thoughts, it was with purpose and passion, expressing powerful convictions formed from a deep erudition and a fierce fidelity to our holy Torah.

He started with an overview of the Seder night — a “fraternity meal,” he called it, in which the members of our “club” — Klal Yisrael — partake. Alas, no hall is large enough to contain all of this club’s members, so each family sets their own table, running identical programs and serving set menus in dining rooms the world over, thus uniting our people in thought and action.

The father of the household presides, our guest said, and Hashem Himself is present as His entire membership joins to imbibe the Yom Tov’s themes of freedom, culminating in the most majestic of words: “V’lakachti eschem li l’am — I will take you to Myself as a people,” describing the first statement of our destiny.

He spoke about what it meant to be an eved, a slave, in Mitzrayim — homeless, powerless, and physically abused, and how each one of those unique dispositions are reflected in the pasuk. When we said the Mah Nishtanah, our guest explained that the ability to question is man’s superiority over beast, his capacity to wonder distinct to the human spirit, serving as the basis for development. He then exhorted us as parents to satisfy our children’s thirst for knowledge, to ensure their incessant questions are not expressed in vain — the very intent of the Haggadah, he explained, in including the four questions.

When we read the Arbah Banim, our guest said that Torah speaks to all generations — those with inquisitive sons who thirst for more Torah knowledge, as well those who have severed their bond with prior generations. When he mentioned the latter, his eloquent voice carried a hint of lugubriousness; we sensed that perhaps this was a struggle with which he was familiar. In such a generation, he said, the Torah counsels us not to respond to the cynical arguments of a youth convinced they have progressed past their antiquated elders, only to reinforce the fundamentals of faith to ourselves, letting the vanity, fruitlessness, and inevitable disappointment lead the wayward generation back to Hashem and His Torah.

And so it continued as we paged through the Haggadah, our guest opening new vistas of understanding with depth, insight, and crystal clear logic. He provided a comprehensive explanation of each mitzvah and how it squared perfectly down to the finest detail, expressing it all with sophisticated language and even stirring lyrical poetry.

Finally, we concluded with Nirtzah, and our most beautiful Seder drew to a close. We bade good night to our guest, the modestly sized purple Hirsch Haggadah by Rabbi Samson Rephael Hirsch, and we gently placed it on our seforim shrank. There he took his place, now a regular in our home.

Yosef Herz works in a Lakewood-based business law firm and is a frequent contributor to these pages.

Treasured Token

Esther Ilana Rabi

Sefer: The Genuine Books of Flavius Josephus

Takes me back to: Rabbi Aryeh Carmell and his wife’s home

I felt all grown up when I went to Neve Yerushalayim in 1980 at the grand old age of almost 18. Until the novelty wore off, and the loneliness set in. My family was wonderful, but far off, both in distance and hashkafah; Los Angeles is halfway around the world from Yerushalayim, and Conservative Judaism turned out to be further in principle from Torah-true Judaism than I’d ever dreamed.

I was on my own, but I didn’t quite feel up to it.

One day, I was studying Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler’s Michtav MeEliyahu with my tutor, and she said, “You know, the man who compiled this lives in the neighborhood. His family takes Neve girls for Shabbos meals.”

I wasted no time in tracking the family down and inviting myself. Throughout the meal, Rabbi Aryeh Carmell answered question after question. And after the meal, hours after bentshing, as he walked me to the door, he said, “Feel free to come back with any more questions.”

I took him up on his invitation sooner than expected — when I got to the bottom of the stairs and remembered something else that bothered me, I turned and ran right back up, two steps at a time. Rabbi Carmell laughed as he opened the door wide to let me in again.

The Carmells were the perfect package for a lonely baalas teshuvah: a rav with endless patience and wisdom, a gracious and insightful rebbetzin, and kind daughters. I soon became a bas bayis there, showing up for supper, Shabbos meals, shiurim that the rabbi gave in his house, and whenever I had a question. After Rabbi Carmell arranged my acceptance to Gateshead Seminary, the family welcomed me to spend sem breaks in their home. (Three years later, they’d make my shidduch and host the vort.)

One Pesach break came just as Rabbi Carmell and his sons completed detailed indexes of all four volumes of Michtav MeEliyahu (the fifth was published much later). When I moved into their home for the month, Rabbi Carmell handed me several boxes of index cards and gestured to more on his desk.

“Can you double-check these citations?” he asked.

This was right up my alley — and much more appealing than Pesach cleaning. I had to ensure every source recorded on every index card was accurate. It was hard work, but it was fun and interesting, and I viewed it as an expression of my gratitude, in some small way, for the enormous gifts the Carmells gave me — room and board, acceptance, warmth, guidance, and the chance to observe an adopted family’s life up close.

Rabbi Dessler taught that gratitude is the basis of Yiddishkeit, and Rabbi Carmell, a student of his since age seven, embodied the trait. Toward the end of Pesach break, his rebbetzin asked, “Would you like to go on a walk on the Old City walls with Abba and me? He’d like to take you out before you go back to Gateshead, to show his appreciation for your work.”

On the way to the Old City, Rabbi Carmell stopped in front of an antique store, hopped out of the car, and soon emerged with a box wrapped in shiny silver paper.

“Here is a small token of our appreciation,” he said as he handed it to me.

It was a 200-year-old set of the historian Josephus’s writings — he knew I enjoyed his work —and inside, an inscription in Hebrew: “As a sign of gratitude for your dedicated and exacting work preparing the indexes for Michtav MeEliyahu… From your rabbi and friend, Aryeh Carmell.”

These worn, musty antique books are hard to read — the covers and pages are delicate and flaking, and they use the old-style f in place of s — but the set remains one of my most valued treasures, reminding me of my precious relationship with a great man and his family.

Esther Rabi is a writer who lives with her family in Yerushalayim.

Generation to Generation

Miri Kroizer

Sefer: My mother a”h’s siddur

Takes me back to: My childhood home

I glanced at the siddur on my bedside table that belonged to my mother a”h, taking in the embossed gold letters that spelled out her name. I thought about my niece, the first granddaughter to carry Imma’s full name. Her bas mitzvah was fast approaching, and this would be the perfect gift.

But this siddur, a tangible connection to Imma, was my most precious belonging — just holding it gave me a sense of connection to Imma’s neshamah.

But was it time for the siddur to perpetuate Imma’s legacy, to belong to someone bearing the very same name once again?

I was feeling more conflicted by the day.

How could I give it to her?

How could I not?

MY mother passed away 28 years ago from a battle with cancer. In so many of my memories, she is holding her siddur: Imma resting on the couch at the end of a long day, davening from her siddur. Imma sitting in bed, feeding the baby as she murmured Tehillim. Abba driving on family trips and Imma sitting next to him in the car, saying Tehillim (these were not directly connected).

Imma never davened like she had to, as if it was a rote obligation; she davened because she wanted to. Imma conversed with her Father, confident that He was listening. She had an active relationship with Him, a relationship that manifested itself in her siddur.

As a teenager, I knew I wanted to daven like Imma, to have that type of relationship. It didn’t come easily to me, but the image of Imma completely engrossed in a silent conversation with her Maker was my inspiration, and I kept trying. With time, the words of the siddur and of Dovid Hamelech began to resonate.

And then, when I was only 24 years old, she was gone. Abba divided up Imma’s personal possessions among the children. More than anything else, I told him, I wanted Imma’s siddur, with its worn pages and frayed binding, her neshamah pulsating in every wrinkled, tear-stained page.

As the years passed, Imma’s siddur became my best friend. It was my connection to Hashem, and to my beloved mother. But now, with my niece’s bas mitzvah around the corner, I had a decision to make. The siddur was the perfect gift, and it was technically free — but it would cost me so much. Too much?

My niece was starting her life as a bas Yisrael; Imma was my inspiration at that age.

What should I do?

Then one day, I picked up the phone to call my niece. I told her about Imma’s siddur and how much it meant to me.

“I think you should have it,” I said. “Will you cherish it? Are you ready to carry on Imma’s legacy?”

“Yes!” she said emphatically, with as much sincerity and conviction as an almost-12-year-old can muster.

At her bas mitzvah, I handed my niece Imma’s siddur, bittersweet tears brimming in my eyes. Since then, she has cherished and embraced Imma’s siddur — and it has embraced her back. I sincerely believe the tefillos embedded in those pages were instrumental in guiding her to become a beautiful bas Yisrael.

Baruch Hashem, my niece recently became a kallah. As she took her place under the chuppah, I stood there and davened. I asked Hashem that she and her chassan merit to build a beautiful home of their own — a place where Imma’s siddur will assume a place of prominence in the young couple’s new life together.

Miri Kroizer teaches in various schools in Brooklyn, New York, and is a lecturer and kallah teacher.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1015)

Oops! We could not locate your form.