Shattered Dreams

Vienna’s Yissachar Dov Kern revisits the childhood horror of Kristallnacht

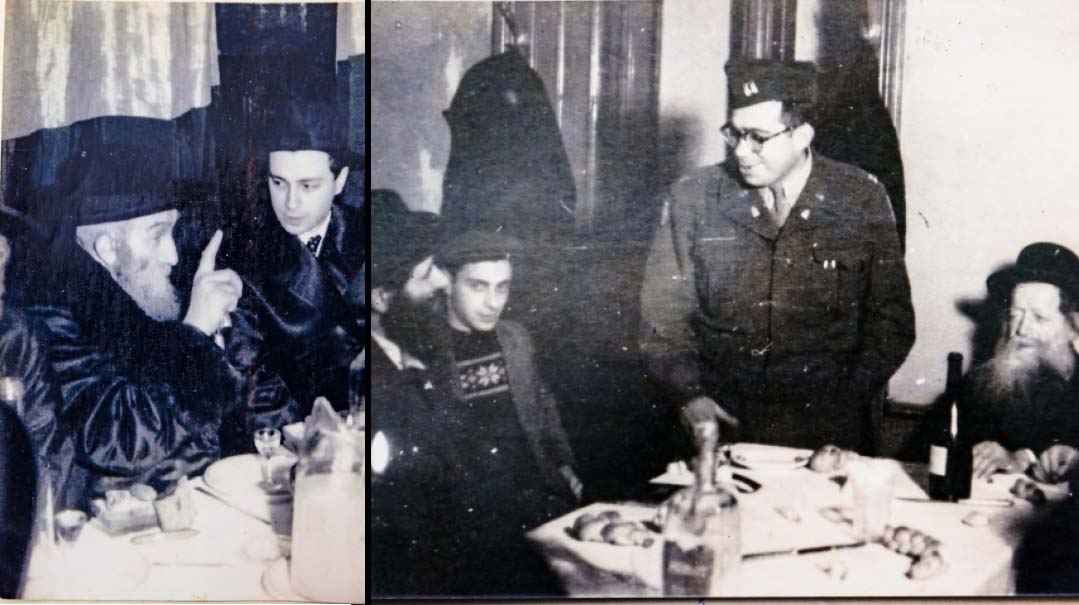

Photos: Chaim Junger

Reb Yissachar Dov Kern stands in the middle of Vienna’s Heldenplatz, the huge Heroes’ Square, and points toward the once-swastika-draped balcony where Hitler yemach shemo stood before nearly a million people in March 1938.

While earnest tourists take photos against the backdrop of the opulent Hofburg Palace, a magnificent remaining symbol of the Hapsburg dynasty, Reb Yissachar Dov, 94, has a more immediate agenda than the Austrian monarchies. Together with his son Reb Shmuel Shlomo, we’re going back 83 years and beyond, to Kristallnacht and the time preceding that horror-filled night, to learn what it was like for an 11-year-old boy facing the unimaginable.

Despite his advanced age, Reb Yissachar Dov is one of the very few survivors who can still tell this dreadful story from its earliest days. He remembers Jewish life in Vienna before the war, the desperate efforts to escape, the escape routes, the concentration camps, and his own brushes with death. His living testimonies are recorded in his heart-stopping book, Lamrot Hakol (Hebrew).

We’re spending an unforgettable day together, as he — with his youthful spirit and vibrant demeanor — brings Vienna of the 1930s to life. Before the war, Austria was home to some 190,000 Jews, about 90,000 of them Orthodox — and the city of Vienna itself was about ten percent Jewish. Today, like then, it is the gateway from Eastern Europe to the West, and thousands of persecuted Jews found themselves a home there in the interwar period.

Vienna became home to a number of chassidic rebbes, and the city boasted some 40 shuls, dozens of chassidic shtiblach, and an array of chinuch institutions. Jews engaged in all types of professions, and some established huge retail chains (such as the still-popular Delka shoe store chain, whose name is actually an acronym for its founder, a Jew named Dovid Leib Keinan). On Rosh Hashanah, both banks of the Danube River (which served as part of an eiruv that encircled the largely Jewish Second District) were filled with Jews reciting Tashlich.

Reb Yissachar Dov’s grandfather, Yisrael Kern, came to Vienna in 1918, after several years on the run from Poland during World War I. In Vienna he continued the family’s previous profession as tallis manufacturer. His only son, Shmuel Shlomo, became successful in the leather business, producing leather belts and garters (the “Sport, Leather, and Apparel by S. Kern and Co.” is still around). The family were Belzer chassidim, and Reb Yissachar Dov was named for the Rebbe who passed away several months before he was born.

Yissachar Dov had a charmed childhood, growing up in a wealthy home with devoted domestic help and respectful neighbors. But then things began to change. He still remembers the chants of his one-time friends:

Jude Jude, Shpok in hut (spit into the hat) / Un zog di mutter (and tell your mother) / Dos is gut (that this is good).

When Jews began to flee from Germany after the Nazis rose to power, the Kern family’s home at Krummbaumgasse 2 filled with refugees. Talk of the impeding Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria, mounted, and it all turned into reality on Friday night of Shabbos Zachor, March 10, 1938, when the Chancellor Schuschnigg announced his capitulation to the Nazis.

Reb Yissachar Dov remembers that fateful Shabbos: “My father was in such shock that when he picked up the Kiddush becher, his hands shook so much that half the wine spilled onto the white tablecloth. But he rallied, and the zemiros poured a layer of hope and consolation over us.”

It was ironic, because the Kern family had actually planned to be in Eretz Yisrael by then. Reb Shmuel Shlomo had made a scouting trip to the Holy Land in the early 1930s together with a friend named Eisen, and they jointly purchased a salami factory. But when Reb Shmuel Shlomo returned to Vienna and told his friends about his plans, they laughed at his naïveté, warned him of the spiritual dangers that Zionism posed, and persuaded him to drop the project. In the end he canceled the deal, yet his partner, stunned as he was by the pullout, carried on with the Eretz Yisrael plan. (The Eisen Sausage factory in Haifa has been a success since its establishment in 1934).

Ispend the night in Reb Shmuel Shlomo Kern’s well-appointed home at Krummbaumgasse 2, the same impressive building where his father, Reb Yissachar Dov, grew up. The entire building belonged to the Kern family and after the war, Reb Yissachar Dov was able to redeem it and restore it to the family’s ownership. A few buildings over is what remains of the legendary Schiffschul, and while much of it is now an empty lot, the community has plans to restore it to its former glory.

We begin our day where he began his for the years of his childhood: the cheder building, still in the same place and thriving, on Malzgasse. He remembers the visits of gedolei Yisrael who lived in Vienna or came to visit — Rav Yisrael of Tchortkov and Rav Mordechai Shalom Yosef of Sadigura, among others. “I remember how the Tchortkover Rebbe went from child to child and asked each one how he was doing in his learning and who his melamed was,” he says.

Eight hundred children attended the Talmud Torah, aged five to bar mitzvah. He remembers the scholarly bochur named Shmuel Wosner, who became one of the poskei hador. The Wosner family lived opposite their house.

When cheder was over, they would go to the Jugendgruppe of Agudas Yisrael, which filled the children’s spare hours with activities revolving around Torah and Yiddishkeit. Reb Yissachar Dov still gets animated when he repeats the stories that the counselors related — treasures of emunah and simchah that would help move him through nearly a decade of constant persecution and fear.

But the morning of November 10, 16 Cheshvan 1938, everything was different.

“I left the house at 7:45, holding my sandwich as I began walking to cheder. Already when I got to Leopoldgasse I saw some friends fleeing the Talmud Torah. ‘The Nazis are destroying the cheder!’ they cried. I didn’t quite internalize what was going on, so I kept walking towards Malzgasse. The street was teeming with Nazis, SS, and SA soldiers. Dozens of Hitler Jugend and others were rioting. They all streamed towards the Second District, where there were plenty of Jews for them to target. On the corner of the street I watched how the Nazis were beating our melamdim, while the principal, Reb Yoel Pollak, was bleeding from his head and face.

“The rioters didn’t suffice with that, though, and they went up to the higher floors of the cheder. They grabbed the furniture and started tossing pieces out the window into the courtyard, whooping and cheering when they saw the objects shattering on the floor. My heart sank when I saw the melamed’s desk breaking into pieces. Then they took the sifrei Torah out of the aron kodesh and unrolled them along Malzgasse. They brought wood and fuel and set them on fire, while the non-Jews celebrated.

“A group of about 25 Hitler Jugend ran after me and my friends. Frightened to death, we tried to take a shortcut through the Im Werd alley. Suddenly the coal dealer, whose shop was in the alley and who we considered a friend, stuck his foot out as I was running, and I went sprawling on the ground. Seconds later, the Hitler Jugend thugs caught up to me and began to clobber me. I thought that was the end, and I davened to Hashem with whatever strength I had left to save me — and b’chasdei Shamayim they had their fill and then left me alone.”

That morning, Yissachar Dov’s grandfather, Reb Yisrael Kern, hurried back from Shacharis at the Belzer kloiz, sensing that something bad was about to happen. Just three days earlier, Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jew who had fled from Germany to Paris, had shot Ernst Vom Rath, a diplomat at the German Embassy in Paris, as a protest of the persecution of German’s Jews. Kristallnacht was exploited as a distorted justification by the Nazi party to unleash a pogrom against the Jews. That horrible night, they destroyed almost all the shuls in Germany and Austria, desecrated the Jewish cemeteries, looted and vandalized thousands of Jewish-owned stores, arrested thousands of Jews, and murdered hundreds more.

“In Vienna, the pogroms started the day after Kristallnacht,” Reb Yissachar Dov says. “When I finally got home, I stood frozen at the window and watched the horrible scenes — how the Nazis hurled all the furniture out of the shuls, unrolled the sifrei Torah into the streets, and burned the whole lot.

“I saw the destruction of the beis medrash on Heidegasse, and how the Schiffschul and the Poilisher shul went up in flames. I also watched the destruction of the Boyaner and Sanzer kloizen. While I didn’t actually see the looting of the more distant shuls, I watched the massive flames that rose up from them.”

Just a few weeks ago, the community in Vienna celebrated a hachnassas sefer Torah at the Khal Chassidim shul — and the procession passed along the same route that 11-year-old Yissachar Dov had fled for his life on the morning of the Kristallnacht riots. And on that spot, 83 years later, as joyous Jews were demonstrating how the Torah will never be destroyed, Yissachar Dov Koren made the brachah “She’asa li neis” at that spot. The resounding “amen” echoed around the world, as people from all over tuned in.

Reb Yissachar Dov explains that although he’s passed this place dozens, maybe hundreds of times, it was the first time doing so in celebration of a new sefer Torah.

“For me, this was the moment,” he says. “Celebrating our survival when the Nazis were sure they’d destroy us, now was right time to thank HaKadosh Baruch Hu for the tremendous miracle of personal and communal salvation.”

It soon became clear to the Kern family that they were living on borrowed time.

In fact, Reb Shmuel Shlomo, the father of the family, had already obtained entry visas to the United States, but they were only dated for May 1940 — in two years’ time. Meanwhile, they knew that they had to escape from Austria no matter what. He thought about temporarily fleeing to Belgium or Holland. But in order to remain in a foreign country, it was necessary to have a passport, and his Austrian passport became invalid as soon as Austria became part of Germany.

There was no choice but to apply for a German passport. It wasn’t so simple. He needed a stack of documents — proof of ownership of a business, an honesty certificate from the police, and an affirmation of full payment of taxes. The Germans wanted to make it hard for the Jews, and at the same time, to milk them for as much as they could.

And that brings us to our next stop on the day’s itinerary: Wiener Rathaus, the Viennese City Hall. It’s a grand structure that takes up an entire block, but we aren’t here as tourists marveling at the intricate stone moldings.

Jews were naturally very apprehensive about visiting government offices at that time. A person knew how he went in but never knew if and how he would emerge. Jews were beaten there in all sorts of gruesome ways — with truncheons, boots, and whips.

“My father came to get his documents,” Reb Yissachar Dov relates. “Suddenly, a brutal SS man grabbed away my father’s ID card and jeered satanically, ‘The card will be returned only if you run three times around the building. Each lap must not take longer than a minute, and if you’re late, you’ll have to go get your documents in the “Brown House” by yourself!’ The ‘Brown House’ on Hirschengasse was the dread of the Jews. It served as the Nazi headquarters and torture chamber of the city. Not everyone who entered came out alive.

“My father was overcome by panic: People much younger and in much better shape couldn’t run that distance in such a short time, but he had no choice. He had to get the documents no matter what. The brute stood there, stopwatch in hand, checking if he had circumnavigated the building in one minute. My father, who kept thinking about his papers, ran with all his might. After the first lap, which was within a minute, my father stopped and the man shouted, ‘veiter — onward!’ The second lap was harder, but he still made it within the time limit. The third lap was also completed in less than a minute, but it didn’t help my father — the evil Nazi simply disappeared with the ID card.”

A little while later, Reb Shmuel Shlomo found out that for a generous sum of money, there was a chance of getting the documents out of the Brown House. “There was a gentile man named Weiser, who would sell rubber to my father’s factory,” Reb Yissachar Dov says. “He had a Nazi relative who was well-connected. He didn’t hate my father, because he made money through him. Now, too, his motivations were purely money. The man named a price: one hundred shilling, about a quarter of a worker’s monthly salary. In exchange, he brought my father his documents and spared him from visiting the Brown House.”

From there, we continue to Prinz Eugen Strasse and arrive at an impressive modern building, the foundations of which stand on a palace that had been owned by the Rothschild family.

“Eichmann yemach shemo sat in this palace,” Reb Yissachar Dov relates. “Anyone who needed to collect a passport came here. There was a very long line that reached all the way to Schwarzenberg Square. Jews had to wait days to get inside, and were meanwhile subject to beatings and humiliation by the Nazi soldiers. Often, when a person finally reached his turn, the Nazi guards came up with some excuse to send him to the back of the line.

“See this sidewalk? This is where I stood,” Reb Yissachar Dov continues. He knew it would be hard for his father to stand on his feet for so many hours, so he volunteered to stand in his place. “At that point, children were not officially beaten, so I came to stand in his place. I brought a little stool and I spent the night on it waiting for our turn.”

It was worth the wait. The next day, they had their passports — everyone except Yissachar Dov’s grandfather, Reb Yisrael. The officials said that one would take another two weeks. The Kern family traveled first to Germany, and from there hired smugglers who, with a huge dose of siyata d’Shmaya, helped them get to Antwerp, where Shmuel Shlomo Kern told anyone who was ready to listen that for him, this stop was only temporary — but no one wanted to listen.

“My father told them what the Germans were doing in Austria, and warned them that they would be next,” Reb Yissachar Dov says. “But the Jews were confident that the Allies would protect them.”

While the Kerns were waiting anxiously for the date that their US visas would become valid, they were making efforts to get their grandfather Reb Yisrael out of Vienna. During that time, Reb Shmuel Shlomo, seasoned salesman that he was, became successful in the diamond industry.

“My visa and that of my cousin Heinie didn’t have a restriction entry date, because unlike our parents, we were born in Austria,” Reb Yissachar Dov relates, “so my father and uncle decided we should go first. They made the preparations and opened two US bank accounts in both our names. Heinie was older than me, but I was only 12 and I was afraid — afraid to go to America alone, and afraid I’d never see my parents again. I the end, I decided to stay in Belgium and Heinie went to America without me.”

When World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, the first to feel the harsh hand of the Nazis in this new state of affairs were the Jews of Vienna. The Jews were considered “dangerous war criminals” and thus, the Nazis arrested a thousand of the city’s Jewish residents whose origins were in Poland, the country against whom they’d declared war.

“Because the prisons were already packed to capacity, they pushed this huge new group into a local stadium,” Reb Yissachar Dov relates. “My grandfather was among the prisoners, and it took a few days for his daughter, my Aunt Gina, to find out where he was being held.

“Years later, I heard from the five Yidden who remained alive out of the entire one thousand, that with them in that stadium was Rav Moshenyu Hy”d, son of the Kopyznitzer Rebbe ztz”l. On Rosh Hashanah, they chose him to serve as their shaliach tzibbur and they told me, ‘Vienna had never seen such a tefillah on the Yamim Noraim.’”

Meanwhile, the Kern family in Belgium made desperate efforts to get Reb Yisrael out. “My father and other relatives finally managed to obtain a visa to Belgium for him, but his captors in Austria didn’t care.” That’s because the stadium was only the first stop. The detainees were squashed into cattle cars and sent to Buchenwald, which at the time was a slave labor camp (and not yet an extermination camp). The train let them off at the station in Weimar, from where they were ordered to march to the camp, amid constant beatings. When the Jews from Vienna arrived, there was no room for them in the existing barracks, so the Germans erected four makeshift huts without walls, and housed them there.

“We were waiting for some news of my zeide, when the telegram came from Aunt Gina in Vienna,” Reb Yissachar Dov relates. “They sent her a message from Buchenwald, informing her that her father had died in the camp and his body had been cremated, and that if there was anyone in the family who wanted to bury his ashes, she should send payment and would get the urn of ashes in exchange. Of course, she paid, and received the ashes delivered to her house. She knew that her father had once prepared dirt from Eretz Yisrael for his burial, so she buried the ashes together with the dirt in the Jewish cemetery in Vienna.”

I wonder: Can we make a stop at the stadium? There’s no event going on now and the gates are probably locked, but we try our luck. We ring the bell and I flash my press pass. To our surprise, the gate opens and we drive in. We go over to the one of the managers and explain who we are. He’s rather uneasy about the whole idea, but grants us entry nevertheless. “Make it short and fast,” he tells us.

Right at the beginning, we notice the monument that has been erected in memory of the Jews who were detained here. From there, we climb a seemingly endless flight of stairs to the stadium. Reb Yissachar Dov is undeterred; he walks all the way up with us, and after a few minutes, we’re inside. We look around, gaping at the sheer size of the place, imagining a thousand Jews being held here, their lives on the line.

From Belgium the Kern family fled to France. From there, they made several attempts to cross the border into Switzerland but were eventually caught — and sent to Auschwitz. Reb Yissachar Dov’s mother perished there, while father and son survived almost until the end. Almost. During the final death march, Reb Shmuel Shlomo was killed — making sure in his death that Yissachar Dov was spared.

Over eight decades later, Reb Yissachar Dov still feels the shock of those moments. “While we were walking, the bandage on my leg loosened, and when I bent down for a moment, one of the Jews noticed that the Nazi guard was aiming his gun at me. ‘He’s going to shoot you!’ he hissed to me and my father under his breath, hoping I’d straighten up in time before the Nazi fired. When my father realized that the murderer was aiming for me, he threw himself on top of me. The bullet that was directed at me hit him instead, killing him instantly.”

The number on Reb Yissachar Dov’s arm has been an indelible testimony to all he endured in Auschwitz and before. It’s a number that’s been burned into his consciousness, but not only because he sees it every day. The number has its own story.

The Allies were closing in, targeting the camps in their bombing raids. In the Blechhammer camp near Auschwitz, the Nazis had installed a network of huge chimneys that dispersed heavy clouds of smoke in all directions in order to blur the bombing targets. The Jews were tasked with taking a rickety elevator to the top of the chimneys in order to activate the system when there was an air raid siren.

“At one point,” Reb Yissachar Dov recounts, “the person who was supposed to activate the system refused to go up, as the elevator wasn’t working. The Jews were terrified that they would be accused of collaborating with the enemy, but it was nearly impossible to climb on ladders alone to the top of the chimneys. They all looked at me, but I refused. There was no way I was going to go up there — it was sure death. The Gorlitzer Rav, the grandson of the Divrei Chaim of Sanz, was there with us. He was a holy Yid, and he pleaded with me to do it, but I still refused.

“And then the Rav asked me to stretch out my hand and show him the number on my arm. He looked at it for a few moments and said, ‘Your mispar kolel is 26, which is numerically equivalent to the Name of Hashem. B’Sheim Hashem, go up there, and you will succeed!’ He even added, ‘Whenever you encounter trouble, look at this number, and like Moshe Rabbeinu who killed the Egyptian with the Sheim Hameforash, you will also be saved with it!’ So I went up those ladders, and came down safely.”

After the war, Reb Yissachar Dov returned to Vienna. First, he decided to wait — maybe some relatives would return? But no one came back. And so he remained alone, doing what he could to revive the decimated Jewish community. With his characteristic strength of spirit, he reestablished himself, and helped rebuild the Jewish institutions. He relates that when he reregistered for the Adas Yisrael community, he was the 24th person on the list. Today, he’s the president of the kehillah.

He, together with a few likeminded friends, were able to locate dozens of Nazi collaborators and turned them in to the Russian authorities. He managed to revive the family business, eventually expanding into real estate.

“I often still ask myself why I alone was spared from my family,” he admits. “But I know that I have no answers, not to this question and not to many other unresolved questions. I look at the flourishing institutions, the shuls, the hachnasas sefer Torah on the spot where I was almost killed. It’s really unbelievable — what a zechus to be part of it. You know, back then we lived for the day, the hour. Who was able to think about tomorrow?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 885)

Oops! We could not locate your form.