Sharing the Wealth

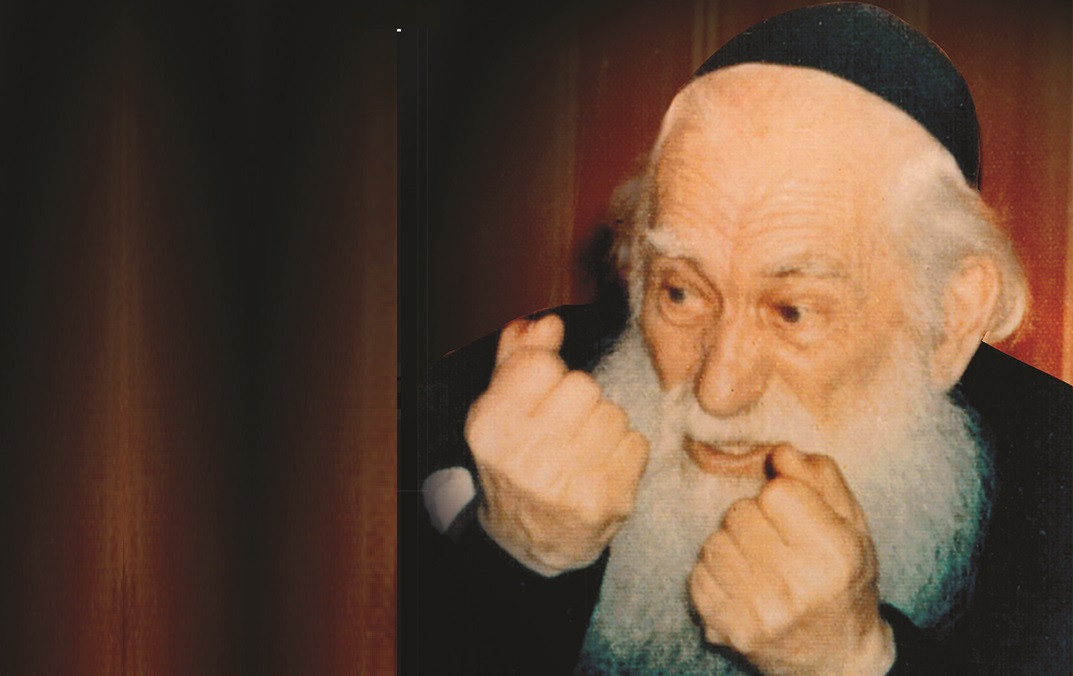

| September 18, 2019“I gave the yeshivah my very bones”: 50 years later, Reb Yaakov “Jackie” Levison remembers the Ponevezher Rav

I

t’s the yeshivah that generated other yeshivos, the great beis medrash at the top of the hill from which Torah has coursed down and illuminated shiur rooms across Eretz Yisrael and throughout the world. Its roshei yeshivah have occupied seats at the mizrach-wall of world Jewry — its very name considered the mother of the olam hayeshivos.

And who was the mother of Ponevezh itself?

At a time when Am Yisrael saw darkness and tasted fear and despair, one man saw hope and a future of light: The Ponevezher Rav, Rav Yosef Shlomo HaKohein Kahaneman, bought a tract of land when others saw no use for it, and started construction while all around him, people scoffed at the unrealistic dreamer.

But if anyone could make the dream come true, it was Rav Kahaneman. When World War I was raging, that didn’t stop him from establishing the yeshivah of Grodna in 1916. Five years before, when he was just 23, he became rav in the Lithuanian town of Vidzh, and when the German occupying forces moved into Lithuania, they granted him permission to travel throughout the area. (Rav Kahaneman made a point of playing chess regularly with a particular high-ranking German officer, which gave him the connections to rescue close to 900 Jewish POWs who would otherwise have been left for dead.) In Grodna, he discovered dozens of displaced refugee bochurim from various yeshivos, and promised that he’d make them a permanent yeshivah, eventually convincing Rav Shimon Shkop to assume its leadership.

His outstanding organizational abilities and far-reaching vision soon became evident. A venerated talmid chacham with a dynamic and winning personality who had learned in Telshe and Radin, he not only devoted himself to Grodna, but established other centers of Torah learning as well, among them a yeshivah in the Lithuanian town of Ponevezh, where he was appointed rav in 1919. The yeshivah became one of the largest in the country, and while running it, Rav Kahaneman also became a leader of Agudas Yisrael and was even elected to the Lithuanian parliament.

Rav Kahaneman was on a mission abroad when World War II broke out in 1939, and made his way to Eretz Yisrael the following year, from where he tried, unsuccessfully, to rescue Lithuanian Jewry from the Nazi clutches. But seeing the utter destruction that would have stopped most people in their tracks — his own family was murdered — seemed to fuel his vision for a future no one around him could comprehend.

The Rav was already close to 60 at the time, but looking up at a hill rising over the few scattered homes that made up Bnei Brak, he thought it would be the perfect location for a yeshivah — he would rebuild the Ponevezh that had been snuffed out by the Nazis. He bought that parcel of land, but no one understood how he could even contemplate embarking on building a yeshivah when Europe was in flames and reports were coming in about the genocide of the Jews. The Nazis were decimating the continent, and their plan was to march toward Palestine, intent on snuffing out the last embers of a nation. But the Rav was undeterred, announcing to the world that he was creating a yeshivah that would serve as a memorial to the great yeshivos that had been destroyed.

The Rav, like everyone around him, was overwhelmed and devastated by the news of the catastrophic losses in Europe, but through the haze of anguish, he knew he had to rebuild. (When the Rav detailed his ideas to Chief Rabbi Rav Yitzchok Herzog, Rav Herzog considered the plan and then gently told Rav Kahaneman, “You’re dreaming.” Rav Kahaneman replied, “I might be dreaming, but that doesn’t mean I’m sleeping.”) The Rav’s plan was to erect a building that would accommodate at least 500 students, envisioning the thunderous sounds of Torah that would emanate from that hill — even as his yeshivah began at the end of 1943 with a mere six talmidim and Rav Shmuel Rozovksy as rosh yeshivah. (Two of those students — one-third of the yeshivah — were Rav Gershon Edelstein shlita and his brother Rav Yaakov ztz”l.)

Within a few short years though, Ponevezh, and its founder, stood tall and triumphant. Just as Yehudah had established a yeshivah in Goshen to welcome Yaakov Avinu and his family, so too did this yeshivah serve as the home and base for the stream of talmidei chachamim that would soon arrive.

The Rav didn’t just welcome them to the yeshivah, though; he took care of their food and accommodations, their wellbeing and happiness. He hired roshei yeshivah and rebbeim capable of rebuilding broken souls, and from the collection of survivors, immigrants, and children of the orchards not far from Bnei Brak, came forth an explosion of ameilus b’Torah.

Some of those talmidim would become devoted as sons, young men who would go on to become roshei yeshivah and rabbanim, dayanim and mashgichim. Others would go into business, but they too would be marked by their rebbi’s stamp. One of these talmidim is Reb Yaakov (Jackie) Levison of London, who, although he never learned in Ponevezh, became the Rav’s confidant, driver, and right-hand man during the Rav’s frequent trips abroad.

In time, people conceded that Jackie Levison was perhaps the closest person to the Ponevezher Rav, who treated him as a son and would even call him “mein kind.”

The Rav himself once remarked, “How can I repay Reb Yaakov? Money, he doesn’t need, and he’s allergic to kavod. All I can do is be his good friend and share what’s in my heart.”

This 20 Elul marks 50 years since the petirah of the great architect and general of the rebirth of the Israeli Torah world, and to appreciate his legacy, there is no one better than his “good friend,” Reb Yaakov, a legendary baal chesed who would literally give over his London home to any meshulach or needy visitor. Since retiring from his real estate enterprises, he has been living quietly and modestly in Jerusalem.

The Levison home in London was famed for the way guests were received there. (There is a famous story of a meshulach who received the Levisons’ address as a place to stay, and while sitting around the table eating breakfast the following morning, he turned to the man next to him and asked, “How long can one stay here?” The man – who unbeknownst to the meshulach was the host himself – answered, “I’ve been here a few years now and no one ever told me to leave.”) Clearly, the Jerusalem apartment, while a little smaller, has been designed to give visitors that same feeling.

We are here together with Rav Menachem Cohen, an old friend of Reb Yaakov’s and longtime Ponevezh talmid and disciple of the Ponevezher Rav. Rav Menachem was the former rosh yeshivah of ITRI Hadera and current rosh yeshivah of Toras Chaim, a former rabbinical board head of Lev L’Achim, and today serves as chairman of Mishpacha’s (Hebrew) Rabbinical Board. In a way it’s a bittersweet reunion for them too, because as they slip into sweet reminiscences, they also note that they’ve just passed the 30th yahrtzeit of another shared rebbi, Rav Kahaneman’s first appointed rosh yeshivah, Rav Shmuel Rozovsky. (Rav Shmuel was joined in the nascent Ponevezh by Rav Dovid Povarsky and Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach, and was later asked by Rav Kahaneman to head the newly founded Grodna Yeshivah in Ashdod.)

Rav Menachem Cohen reminds Reb Yaakov of the time they traveled together to various holy sites, newly accessible after the Six Day War, together with Rav Rozovsky. At the time, Rav Menachem wondered why their rosh yeshivah had been so emotional at the Kosel, yet had seemed more reserved at the Mearas Hamachpeilah.

“I wasn’t brave enough to ask, so Reb Yaakov, you asked for me — do you remember?” he says as he turns to his old friend.

Reb Yaakov completes the story. “Rav Rozovsky heard the he’arah and he explained, ‘I know who the Avos were, but what personal connection do I have with these larger-than-life ancestors? To the Beis Hamikdash I feel more personal — I learned Zevachim, I learned Menachos, I learned the Rambam, so I feel a more intimate connection to it — I can actually see the avodah in my mind’s eye, and in a way it’s easier to mourn when I stand here.’”

Rav Menachem shares another story about Rav Kahaneman from the period when the Rav was unwell and forced to undergo a complex operation in America. “Who was with him? Reb Yaakov Levison, of course,” he says as he looks appreciatively at our host. “A wealthy Jew from Chicago named Eisenberg came to the hospital, and stayed by the Rav the entire time. Reb Yaakov asked him, ‘Are you a relative of Rav Kahaneman?’ He said he wasn’t related — but there was a good reason he was there. He recalled how when the Russians took over Lithuania in the beginning of the war, they installed a new Lithuanian government and restored the city of Vilna to that country. This man had been together with Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky when he heard that the Lithuanians had regained Vilna, and he saw that the gadol greeted the news with joy. Rav Chaim Ozer exclaimed, ‘Now I will be able to meet the Ponevezher Rav!’ Eisenberg told Reb Yaakov, ‘If it meant so much to Rav Chaim Ozer, how much more choshuve should it be for me?’ ”

The Levison family owned a car in 1956, when there was still a long waiting list in London for automobiles. And so, Jackie-Yaakov had the merit of driving the Rav around. During the many hours spent together, he earned the Rav’s trust.

“The Rav had a notebook,” Reb Yaakov recalls, “in which he had written down the names of all the netzivim in London. The last time the Rav was in London, he left the notebook in my keeping, with the lists of all the donations. Here,” he says, “I’ll even show you the notebook.”

Reb Yaakov gets up and brings the old bound notebook from an adjoining room. “The Rav gave this to me to keep until he returned. But he never returned….

“I always say that the notebook should be buried with me, so that maybe I can return it to him in the Next World.”

Rav Kahaneman might have been happier sitting and learning Torah in his beloved beis medrash, but he had an institution to maintain, and with his faith in the pintele Yid, believed that deep down, everyone wants to contribute to Torah. And so, this tremendous Torah scholar and yeshivah builder packed his bags and found himself abroad, traveling the world in order to sustain his growing institution. For some, it might have been a bushah, but Rav Kahaneman was indefatigable. It was an extension of that same positive, forward-thinking spirit that caused the Rav to declare back in the early 1940s when it appeared that the secular kibbutzim would be the new face of the Holy Land, “Write tefillin and mezuzahs for the children of Ein Charod and Nahalal!” These kibbutzim were bastions of secular ideology, but Rav Kahaneman was convinced that one day, all of Eretz Yisrael would be filled with Jews coming back to Torah and tradition.

With all that infectious energy and fighting spirit, who wouldn’t want to be a part of Rav Kahaneman’s holy mission?

One of those who joined his cause was the great British philanthropist Sir Isaac Wolfson. “It turns out that he would get a donation of 1,800 pounds sterling from Sir Isaac Wolfson every two months, a staggering amount of money,” Reb Yaakov remembers. “But one time, Sir Isaac Wolfson decided not to send the money straight to the yeshivah, but through Heichal Shlomo, the seat of the chief rabbinate, for various bureaucratic reasons. [Wolfson sponsored the building of Heichal Shlomo.] The Rav told me, ‘How can I take money from Heichal Shlomo, that the Brisker Rav was against?’ So after that, he stopped taking his money for the yeshivah. How many people do you know who would do that?”

Rav Menachem Cohen shares a memory of his own. “The first shiur I heard from the Rav was back in the old beis medrash, which is currently the yeshivah’s lunchroom. I was a young bochur of 15, and the Rav gave an opening shiur on the first day of the zeman. In the middle of the hall, a shtender was set up and all the bochurim crowded around to hear. But then, right in the middle of the shiur, a taxi driver entered the yeshivah, elbowed his way through the crowd and approached the Rav. He whispered something to the Rav, who said ‘Tell him to wait. In half an hour I’ll finish the shiur and come to him.’ The driver left, then returned with a message, ‘He doesn’t have time. If the Rav doesn’t come now, he’ll leave.’ The Rav thought a moment and then said, ‘So let him leave.’

“That night, the Rav said a shiur to the older bochurim, and Rav Tzvi Drabkin — today rosh yeshivah in Grodna — told me that before the shiur, the Rav told the bochurim what happened: ‘Today,’ Rav Kahaneman told them, ‘you probably heard that a driver came in during my shiur and whispered something to me — now I’ll tell you the background. Yesterday Rav Moshe Portman, our menahel, told me that the yeshivah pantry had just enough food for one more day, and no stores would extend credit to the cook for more ingredients. We need to feed the bochurim, but what can we do in one day? I called a good friend, Reb Nochum Genachowsky, and told him we’re running out of food. He’s a busy trial lawyer, and told me he was very busy with a court case and couldn’t come over to help, but he had some good news. He told me that he has a friend from America who came to Eretz Yisrael with $5,000 to distribute to tzedakah, and this friend asked him for a list of needy people and institutions. Reb Nochum told him to put Ponevezh at the top of the list, and the man in the taxi was that Jew from America, sent by Reb Nochum to help me.’

“Rav Kahaneman went on to tell his talmidim how the driver informed him that his passenger was in a rush and couldn’t wait. But he made a calculation: The bochurim needed to eat and no doubt, the donor came with funds, while the shiur could be continued later in the day. ‘But then,’ the Rav continued, ‘I felt that here’s an opportunity to show the bochurim that nothing is more important than Torah, so I decided to let him go.’

“But the passenger, taken by the Rav’s authenticity and strength of character, decided to remain and wait, leaving the yeshivah with enough money to feed the bochurim for two months.”

But, says Rav Menachem Cohen, that wasn’t the end of the story. After his generous contribution, the donor asked the Rav a favor. He’d had an illustrious grandfather, a Torah scholar. He would donate money to upgrade the beis medrash, but he wanted a picture of his grandfather to hang there.

The Ponevezher Rav heard the proposal and made a counteroffer. “You’re not familiar with this country,” the Rav said. “But you should know — who sits in the beis medrash? A few impoverished bochurim. What honor will it give your grandfather if they see his picture? But the yeshivah’s office is a respectable place, visited by businesspeople and officials. If we hang it there, it will get noticed.”

The portrait hung there for several years.

The incident reminds Reb Yaakov Levison of a similar story.

“There was a family in London who offered a large donation to the yeshivah, but they wanted their names to adorn the two chairs affixed to either side of the famous aron kodesh in the beis medrash.”

“I can’t do it,” the Rav told them. “Those places aren’t mine to sell.”

The family wondered who they were meant for, and the Rav told them.

“One is for Mashiach and the other for Eliyahu Hanavi, and they’re coming soon. Where do you think Mashiach will go first? Only to a yeshivah… and which yeshivah? Ponevezh, of course! I can’t sell those chairs for all the money in the world.”

These two elder talmidim reflect on the connection between Rav Kahaneman and his own rebbi, the Chofetz Chaim.

“The Rav learned in Novardok, where the Alter asked him to give chaburos for bochurim,” says Rav Menachem. “Once, on his way back home to Telshe, he decided to take a detour and go see the Chofetz Chaim. He came to the house and the Rebbetzin told him to wait, because the Chofetz Chaim was busy. Suddenly he heard frightening cries, but the Rebbetzin told him not to be afraid — her husband was only davening for a woman in labor. The young visitor reasoned that if the Chofetz Chaim felt the pain of another that deeply, then this would be his rebbi.

“The Chofetz Chaim came to greet Rav Kahaneman, and told him that he wanted to found a Kollel Kodshim. The Rav, just a bochur at the time, said, ‘I don’t want to learn Kodshim, I want to learn Nashim-Nezikin.’ The Chofetz Chaim said to him, ‘You’re a Kohein. If Mashiach comes tomorrow, what will you do? How will you know how to do the avodah?’ ‘I’ll see what the Chofetz Chaim does and I’ll follow him,” Rav Kahaneman replied.

The Rav later told his talmidim that he never forgave himself for that answer.

“The Rav told us how the Chofetz Chaim would give a mussar shmuess to the bochurim every evening,” Rav Menachem continues. “One day the bochurim came to his house and saw that he was editing the copies of Mishnah Berurah that had just arrived from the printing house. He would edit every book, and in old books you can see written in his handwriting, ‘mugeh.’ The Chofetz Chaim told them: ‘Can I give mussar to the bochurim on a day when I didn’t learn?’

“The Rav used to tell us that was the best mussar he ever heard. He told us how all the bochurim returned to the yeshivah to learn and the whole yeshivah skipped dinner in order to continue learning.”

Rav Menachem shares another vivid memory. “When Rav Nissim Toledano (later Rosh Yeshiva of Sheirit Yosef and member of the Litvishe Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah) got married a few days before Rosh Hashanah, the Rebbetzin made a shevah brachos on the first night of Yom Tov, to which she invited some of the bochurim. The Rav said that although levity on Rosh Hashanah wasn’t appropriate, there is still a mitzvah to make the chassan happy, so instead of singing and dancing, he told us stories of his rebbi the Chofetz Chaim all night, right up until the time for Shacharis.”

Reb Yaakov recalls meeting Rav Shlomke Berman, the prize talmid of Ponevezh and eventual son-in-law of the Steipler.

“Rav Shlomke asked me,” said Reb Yaakov, “if among the stories I’d heard from the Rav about the Chofetz Chaim, had I heard the one about his meeting with Eliyahu Hanavi?

“I had never heard it, so Rav Shlomke told me: ‘The Ponevezher Rav once knocked at the Chofetz Chaim’s door, and the Chofetz Chaim came out accompanying a particular Jew. Afterward the Chofetz Chaim asked him, did you see that Jew? He said yes. So he told him to recite the pasuk one says upon meeting Eliyahu Hanavi.’”

Rav Menachem turns to him. “Did you know that as a bochur, the Rav learned with the famous mekubal, the Ba’al HaLeshem? They learned Gemara, not Kabbalah, but he told me that after their learning sessions, he would walk home, late at night. After learning with the Leshem, the Rav said that every tree looked like a malach.”

It was the summer of 1969, and Rav Kahaneman’s neshamah was fighting for release from its guf. As talmidim were taking their final leave from their rebbi, word spread that there was a generous donor who wanted to give money to the yeshivah, but someone had to travel to America and accept the funds.

Reb Yaakov Levison was the messenger.

He missed his rebbi’s levayah.

“Back then,” says Rav Menachem, “I shared a story about the Kotzker Rebbe, whose own rebbi, the Peshichsa Rebbe, asked him to be his messenger in an urgent business. A few hours later the Peshichsa Rebbe passed away, and the Kotzker wasn’t there for the levayah. When the Kotzker returned from his mission, people asked him, ‘How can it be that you, one of the greatest talmidim, weren’t at the levayah?’ The Kotzker answered: ‘Actually the only one who was at the levayah was me.’

“Reb Yaakov was the one who was at the levayah.”

“It was just before yetzias haneshamah,” Reb Yaakov fills in the details. “Rav Avraham Kahaneman, the Rav’s son, said that someone had to fly to America to accept a very large donation.”

“That’s a story about Rav Avraham,” Reb Menachem exclaims, “how even at that moment he still thought about the yeshivah. He inherited that sense of mission. The two of them lived for something bigger.”

The comment reminds Reb Yaakov of a conversation he once had with Rav Kahaneman.

“I once asked him how he had the selflessness to hire such illustrious roshei yeshivah. How does a person forfeit his own honor by bringing in those who will outshine him?

“The Rav heard the question and said it was based on a mistaken premise. ‘First of all,” he said, ‘it doesn’t diminish me, because the more distinguished the Ponevezh yeshivah is, the greater the gadol I’ll be considered. Secondly, I give the yeshivah my life, my strength, my health, my very bones — am I going to sacrifice all that for my kavod?’

“The first part of the answer was a cute joke, but the second one was strange: I didn’t understand what the Rav meant with the words ‘my very bones,’ until years later.”

Several years later, the Rav called his beloved talmid into the office and asked him to close the door, so that they would have privacy.

“Our creditors and suppliers are knocking on our doors — it can’t continue this way. Now, you know that I bought a plot of land to build a cemetery on in the future, and they’re urging me to open it now so we can have a bit of income from selling the burial plots.

“Fools!” the Ponevezher Rav continued. “If we open the cemetery now it will be just another graveyard. No one will pay much to be buried there, because what’s the honor? But after 120 when they’ll take my bones and bury them there, then it will become an honorable — and lucrative — burial place.”

“And that,” says Reb Yaakov, “was how he established the Ponevezh beis hachayim, which brought in so much money for the yeshivah… and that’s what my rebbi meant by his bones — he gave it all up to the yeshivah, his entire essence, down to the bone.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 778)

Oops! We could not locate your form.