Settling Unfinished Scores

A half century after the guns fell silent over Sinai and the Golan, revisiting the climactic scenes on the front and those inside the heart

Photos: Government Press Office

The Yom Kippur War of 1973 marked the third time in 25 years, starting with the War of Independence, that the State of Israel faced menacing battles on multiple fronts against enemies with more manpower and weaponry.

For the third time, Israel prevailed, but this time, the victory was more bitter than sweet. As the state commemorates the 50th anniversary of the war that broke out on the most solemn day of the Jewish calendar, we offer our review of the backdrop, the battles, some of the heroes and some of the goats, and how this war reshaped reality in the Middle East

IN many respects, the 1973 Yom Kippur War was Act II of the 1967 Six Day War, which ended in a miraculous Israeli victory over Egypt, Syria and Jordan.

In 1967, Israel had captured the Sinai, an area almost three times the size of New Jersey, from Egypt in the Six Day War. Israel also recaptured Judea and Samaria, its Biblical heartland, from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria. The Sinai also has strategic importance, as its western border abuts the Suez Canal, one of the world’s most important shipping lanes. For a few short years, Sinai’s oil wells provided Israel with a level of energy independence it never had before. Refusing to accept defeat, Egypt led a coalition that included Jordan, Syria, and at times, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in what became known as the War of Attrition, attacking Israel by land, sea, and air hundreds of times between 1967 and the summer of 1970.

The War of Attrition claimed almost twice as many Jewish lives as the Six Day War and finally ended with a cease-fire in August 1970, which Egypt and its military sponsor — the Soviet Union — broke almost immediately by stationing surface-to-air (SAM) missiles in the Sinai Peninsula well past the agreed-upon cease-fire lines.

For three years, there was relative quiet, and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat used the lull to prepare for the next war.

For Israel, it couldn’t have come at a more inopportune time. At 2 p.m. Israel time, on Yom Kippur, Egypt and Syria launched a massive attack on the territories that Israel had captured from them in 1967.

Their war plans were predicated on fully surprising Israel, using their superior manpower to hamper Israel from defending the Golan and the Sinai simultaneously, with a goal of reaching the Jordan River within 24 hours and capturing the slopes of the Jordan before Israel could mobilize its reserves.

The first few days of war rudely shattered Israel’s aura of military invincibility. The old jokes from 1967 about Arab tanks being equipped with back-up lights were no longer humorous.

Israel was indeed caught by surprise. In the months and weeks before the war, IDF military intelligence repeatedly downplayed multiple warning signs of an imminent attack. Much of the IDF, including almost all of its reserves, were on leave, attending synagogue services in their hometowns, and the IDF left many strategic border posts unmanned or undermanned. Israel entered the war with 358 fighter jets compared to 998 for its enemies. Enemy tanks outnumbered Israel by 4,350 to 2,100 and there were 137 Arab naval vessels compared to Israel’s 37.

Unlike during the Six Day War, Israel’s political echelon decided not to launch a preemptive attack against the enemy forces because they feared they would lose international support for what proved to be a lengthier battle than expected.

In the war’s first two days, Egyptian tanks, backed with SAM anti-aircraft missiles, easily crossed the Suez Canal, seizing a strip of about ten miles of Israel-held Sinai. Syria recaptured strategic outposts on the Golan Heights, and had they pressed on, could have launched an offensive toward Lake Kinneret and northern Israel.

Despite the early reversals and the manpower and weaponry advantages the Arabs enjoyed, Israel, with Hashem’s help, chased the invaders out in 18 days, leveraging a combination of individual bravery, superior artillery skills and airpower, and the flexibility of its command structure to switch from defense to offense in the heat of battle. The war ended with IDF troops 77 miles from Cairo and 25 miles from Damascus.

Fifty years is not as long as it seems, and the lessons learned on the battlefield, and in the halls of political power, remain as relevant today as they were in 1973.

THE POLITICAL MACHINATIONS

1969-1973

Land for Peace, Nixon-style

Politically speaking, Israel was relatively stable in the post-1967 years. Levi Eshkol, the prime minister who presided during the Six Day War, passed away in February 1969, and Golda Meir took over, retaining the national unity government she inherited from him.

In America, Richard Nixon took the oath of office one month before Meir took power in Israel.

One of Nixon’s foreign policy goals was to reduce tension with the Soviet Union, which was the Arab world’s prime military and political sponsor.

On December 9, 1969, Nixon’s secretary of state, William Rogers, unveiled a comprehensive peace plan calling for an Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai. Israel rejected this a day later, labeling the Rogers plan an attempt to appease the Arabs at Israel’s expense. The Arabs also rejected the plan, claiming the US was biased toward Israel.

October 15, 1970 – Summer of 1973

Change of Command in Egypt

Anwar Sadat takes over as president of Egypt, replacing Gamal Abdel Nasser, who died of a heart attack. Sadat declared 1971 to be a “year of decision,” claiming his readiness to sacrifice a million Egyptian soldiers to recover the territory his country lost to Israel in 1967.

Sadat also offered several initiatives to normalize relations with Israel in return for a staged withdrawal from the Suez Canal area, to be followed by a complete Israeli return to the pre-1967 borders. Israel rejected these offers as one-sided.

Sadat Appoints a War General

October 1972 – April 1973

By October 1972, Sadat informed his top army brass in private meetings to prepare for war. Sadat promoted General Saad Al-Shazly to chief of staff. Al-Shazly crafted Egypt’s strategy — a war of limited objectives to cross the Suez and seize and hold up to eight miles of the Sinai as a bargaining chip for a cease-fire and ultimate Israeli withdrawal.

In April 1973, Egypt and Syria agreed to coordinate battle plans for a war to begin in May, but Syria’s insistence on deeper Egyptian penetration in the Sinai forced a postponement. Both sides agreed on a new date of October 6, when the moon would set at midnight, providing a cover of darkness for Egypt to build bridges for a Suez crossing.

Summer of 1973

The Plot Thickens

Egypt acquired several hundred water cannons from Germany to penetrate Israeli embankments along the Suez Canal, and purchased Soviet pontoon bridges to cross the canal. Israel still failed to read the signals, partially because Sadat had already mobilized his forces along the Suez twice that year. On both occasions, Israel called up its reserves at considerable expense, but this time, IDF intelligence figured either Sadat was holding another training exercise or just bluffing.

Late August 1973

Sadat Builds Political Bridges

Sadat “disappeared” from public view for five days. On August 28, the New York Times explained the five-day blackout, reporting that Sadat visited Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Syria to “tighten his relations with the oil–producing countries of the Persian Gulf and to mobilize Arab oil wealth against Israel.”

Israeli historian Benny Morris says Sadat tipped off Saudi King Faisal on August 23 of the planned attack and raised the idea of an Arab oil boycott against supporters of Israel.

September 1973

Final Preparations

At a tripartite summit in Cairo, Jordan’s King Hussein agreed to a coordinated military command under Egyptian control, although he told Sadat that Jordan would not be a combatant. King Hussein reportedly warned Israel on September 25 of Sadat’s plans, but the head of IDF intelligence, Major General Eli Zeira, was tone-deaf. He stuck to his longstanding position that Sadat lacked personal motivation and his forces lacked the military capability to attack.

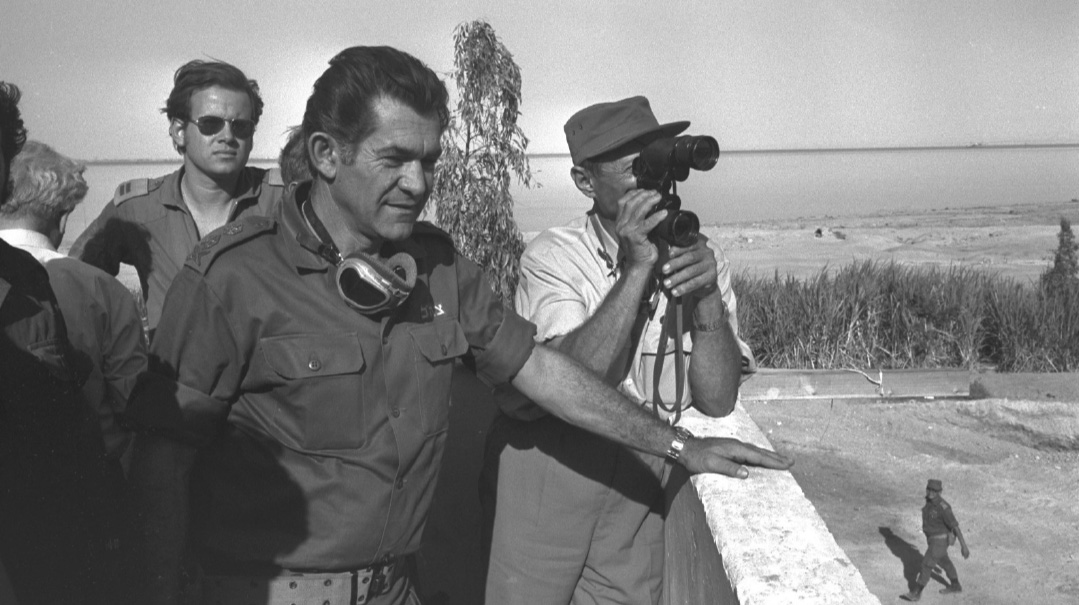

Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Chief of Staff David Elazar at an IDF outpost near the Suez Canal

THE BATTLES BEGIN

Erev Yom Kippur

An Unmistakable Warning

The Soviets evacuated the families of its military advisors from Egypt and Syria. IDF intelligence intercepted an encrypted telegram from the Iraqi embassy in Moscow saying the reason for the evacuations was an impending war. A Mossad agent in Egypt, just recently identified as Ashraf Marwan, the son-in-law of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser, warned Israel of the time and date of the attack, although he told them it would start at 6 p.m., not 2 p.m. This has led to speculation, which Mossad head David Barnea denied last week, that Marwan was a double agent and was also spying against Israel for Egypt.

Yom Kippur morning, 4 a.m.

Opening Salvos

IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar asked Prime Minister Golda Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan for permission to launch a pre-emptive strike at enemy positions. Meir and Dayan rejected the idea for fear that Israel would look like the aggressor.

Ten hours later, the Arabs attacked, as some 200 Egyptian warplanes bombed Israeli military installations along the Suez Canal and 70,000 Egyptian troops with 1,000 tanks started crossing. Simultaneously, two Syrian armored divisions with 40,000 troops and 650 tanks attacked Israeli positions on the Golan Heights, manned by fewer than 7,000 IDF soldiers and 200 tanks.

Early Losses and Heroics

An elite Syrian commando captured a key Israeli electronic surveillance base at the top of Mount Hermon. Four Syrian brigades slashed through the southern Golan, heading straight for Israel’s divisional headquarters, where Lieutenant Zvika Greengold, who lived to tell his story, fought them off with a single tank for hours until help arrived. Shmuel Ashkarov, a deputy tank battalion commander, singlehandedly destroyed 30 Syrian tanks with his tank.

At 3 p.m., thirteen hours later, the commander of the 132nd Syrian Armored Brigade cabled his superiors: “I see the whole Galilee in front of me, request permission to proceed.” His request was inexplicably denied. Some analysts contend Syria’s military was satisfied with reaching its first-day goals and didn’t have the tactical sense to press its advantage.

In the first three days of the war, Egypt and Syria destroyed 500 IDF tanks, or 25% of Israel’s tank force. Along the Egyptian front, Soviet-made SAMs shot down 49 Israeli fighter jets, while Egyptian troops dug in on Israel’s side of the Suez, but went no further, having achieved their strategic goal of capturing a slice of the Sinai.

A Syrian T-62 tank with his turret blown off on the Golan Heights

ISRAEL’S COMEBACK

October 8-12

Taking Down Syria

Syrian and Egyptian hesitation played into Israel’s hands. On Day Three of the war, Israel was fully mobilized on both fronts, but concentrated its reinforcements in the north to defend its population centers in the Galilee region. IDF commanders defended the main roads to keep Syrian forces at bay. Lt.-Col. Avigdor Kahalani ordered his men to attack only moving targets and advancing units, and not waste munitions on stationary targets, halting Syrian momentum and causing them heavy losses. The Israel Air Force bombed the Syrian general staff and air force headquarters in Damascus and the entire electricity-generating capacity of the city.

Demoralized by their losses, Syrian forces began retreating behind the Purple Line (the Six-Day War armistice lines). By October 12, seven days into the war, Syria was neutralized and Israeli forces were positioned 25 miles from Damascus.

Cutting Egypt Off at the Pass

A small patrol under 14th Brigade Commander Amnon Reshef managed to split the Egyptian armies and establish a strategic Israeli beachhead at the Great Bitter Lake, in the center of the Suez Canal region. Division Commander Ariel Sharon was itching to exploit Reshef’s breakthrough with a major invasion, but the IDF brass dithered.

It was then that Egypt’s General Al-Shazly made the major unforced military error of the war. To try and stave off the expected IDF counteroffensive, Al-Shazly launched an ill-advised offensive of his own, overextending Egyptian troops, leaving them without anti-aircraft cover, their armor open to attack, and the Suez unguarded.

The Decisive Battle

Military experts contend the October 14–17 Sinai battle was the turning point in the war and an unmitigated disaster for Egypt. Exposed to Israeli air power and armor, Egypt lost 250 tanks on October 14. With Egyptian armor no longer guarding the Suez, the IDF finally approved Sharon’s plan to cross the canal on October 16.

Within a day, Israel had placed two full brigades with hundreds of tanks on Egypt’s side of the Suez, effectively cutting the Egyptian army into two parts and destroying many of their remaining SAM missile sites.

President Nixon (C), Secretary of State Kissinger (L), and Yitzchak Rabin meet at the King David Hotel to coordinate positions

INTERNATIONAL INTERVENTION

America to Israel’s Rescue

These battles were not occurring in a vacuum. Despite initial Israeli setbacks, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger believed that Israel would win quickly. When he saw that wasn’t happening, he advised Nixon to resupply Israel so it could hold its own in battle for at least one or two weeks longer. Kissinger proposed the US and Soviet Union call for an end to the fighting based on a return to the 1967 cease-fire lines. The Soviets and Israel agreed, but Egypt rejected it.

The US started Operation Nickel Grass in the second week of the war, airlifting some 8,755 tons of military equipment to resupply Israel’s battlefield losses. The Soviets began their own massive airlift to Egypt and Syria.

Don’t Win Too Big

A regional war had now turned into a competition between the world’s superpowers.

While the Nixon administration sided with Israel, it also feared that an Israeli march toward Cairo and Damascus could force the Soviets to intervene militarily to defend the Arab capitals. Nixon and Kissinger’s goal was to end the war without either of the combatants holding the balance of military power so that they would enter negotiations on a somewhat equal footing. Nixon was also afraid that the longer the Arab armies held their own, especially following the Soviet airlift, the more it would enhance Soviet prestige in the region at America’s expense.

Kissinger Greenlights Israel

When it became obvious that Egypt was facing catastrophic losses, Sadat relented and told the Soviets he was ready for a cease-fire. Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev invited Kissinger to Moscow to negotiate the agreement, which ultimately formed the basis for the October 22 UN Security Council Resolution 338 to end the hostilities and start peace talks. However, Kissinger stopped off in Israel before returning to Washington and told the Israelis the US would not object if the IDF continued to advance while he flew back to Washington.

Cairo at Risk

By the time Kissinger arrived back in Washington on October 24, the IDF had completed its encirclement of the entire Egyptian Third Army, which was trying to hold on to the southern part of Israel’s side of the canal. Encouraged by the lack of resistance, the Israeli government ordered IDF General Avraham Adan to conquer Suez City, in the southern part of the Canal region, a mere 77 miles from Cairo as the crow flies. Adan’s attack provided cover for the IDF’s 252nd Armored Division to complete the encirclement of the Third Army by seizing the Adabiya Port on October 24.

Red Alert

Sadat begged for Soviet troops to save his army, but Brezhnev was unwilling to comply. The Soviet leader did, however, send Nixon a hotline message suggesting a joint US-Soviet force to implement the cease-fire. If the US refused, Brezhnev said he would act unilaterally.

The next day, Nixon raised the military alert for all US forces around the world to DefCon III — in essence, the highest stage of readiness for peacetime conditions. White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, who sometimes had a penchant for hyperbole, called it “World War III in the making.” Brezhnev got the message and backed down.

Finally, a Cease-Fire

The UN also swung into action that day, approving Resolution 340 on October 25, calling for all sides to adhere to the cease-fire and withdraw troops to the positions they held three days before Kissinger gave Israel the go-ahead to advance. This times, all parties to the conflict agreed, bringing the Yom Kippur War to an end. On November 11, Israel and Egypt signed the formal cease-fire agreement, and a month later, opened disengagement talks in Geneva.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.