Set in Stone

| August 16, 2022A creative team coaxes art to the surface of marble slabs

Photos: Avi Gass

The first time it happened, Arin Jéda was in the Bobover beis medrash in Boro Park. As he waited for the next Minchah minyan to come together, the teenager noticed how the marble swirling veins on the wall looked like a tiger leaping over a pile of stones. But when Jéda tried pointing out the image to his fellow mispallelim, they told him he was crazy.

Over the next 28 years, Jéda, a pseudonym for an artist who prefers to remain anonymous, found more images that no one else seemed to be able to see. He finally found a kindred spirit in his wife’s father, who also had an artistic flair and was intrigued by the concept. Propelled by his father-in-law’s enthusiasm, Jéda made numerous trips to various tile stores in search of a promising specimen, and he struck pay dirt with a stone whose veining depicted the image of an elderly man holding a skull in his hands.

“It was profound,” says Jéda. “It was out of the box. It was art. My father-in-law loved it and he encouraged me to find a way to share it with the world.”

Jéda began fine-tuning the concept, painting and drawing the images he saw and experimenting with projectors and e-art. In time he partnered up with Jay Zelingold, a marketing strategist who appreciated that the idea had serious potential if it could be developed professionally, replicated and systemized.

One in a Million

Typically, art is the expression of an artist’s inspiration, but Jéda’s concept was the opposite — discovering inspiration from expression that already exists in nature.

“We worked together and created a few pieces, slowly proving that the concept worked until eventually we realized that we had a model we could run with,” says Zelingold.

Zelingold launched ALMA Art, a collective with multiple artists involved, and is its managing director, while Jéda has taken on more of an advisory role, although he’s the artist of note for most of ALMA’s current pieces. ALMA, which translates to “world” or “earth” in Aramaic, is also an acronym for Accentuated Light Mapping Art, a process which took a full five years to develop and perfect, and uses beams of light to highlight images embedded in slabs of quartzite, marble, onyx and granite.

Finding a stone with potential is no easy feat. “We go through tons of stones till we find one with art-scene potential and, even then, we need to go through tens, oftentimes hundreds, of them, to find one with an actual, compelling image,” says Jéda. “It’s like a diamond — one in a million — and when we find one, we celebrate.”

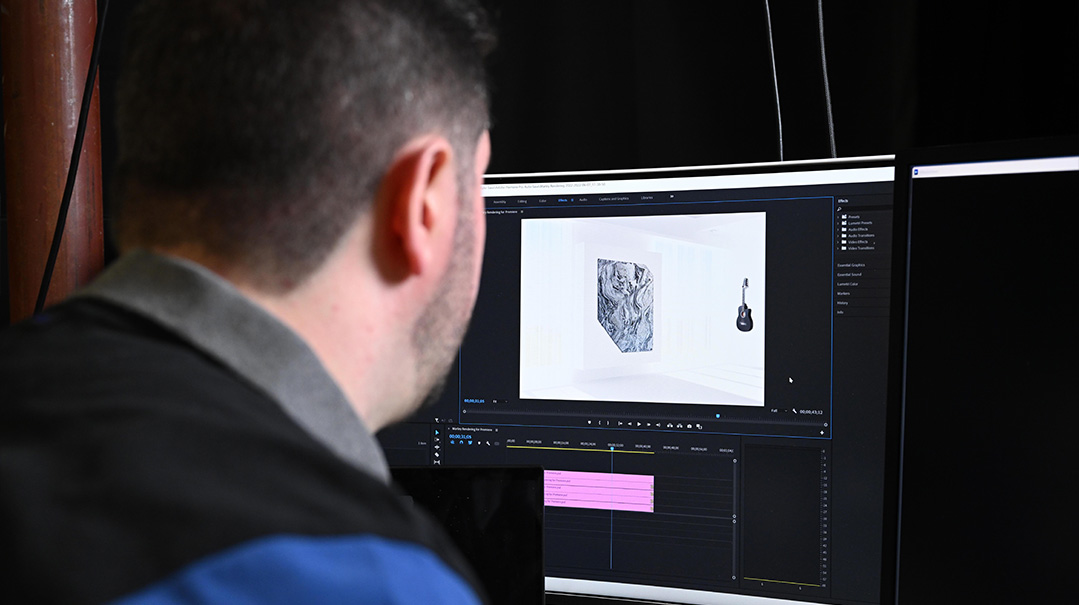

The process of creating a finished piece of ALMA art involves considerable intricacy, complexity and precision, and significant amounts of talent. Old fashioned artistry and cutting edge technology both come into play, as a digital light overlay highlighting specific veins within the slab is calibrated and projected onto the stone, accentuating the existing image and, in turn, bringing it to life.

“What’s amazing is the idea that this is a story that’s found in nature,” notes Zelingold. “We’re not just painting another painting. This is all about the stone.”

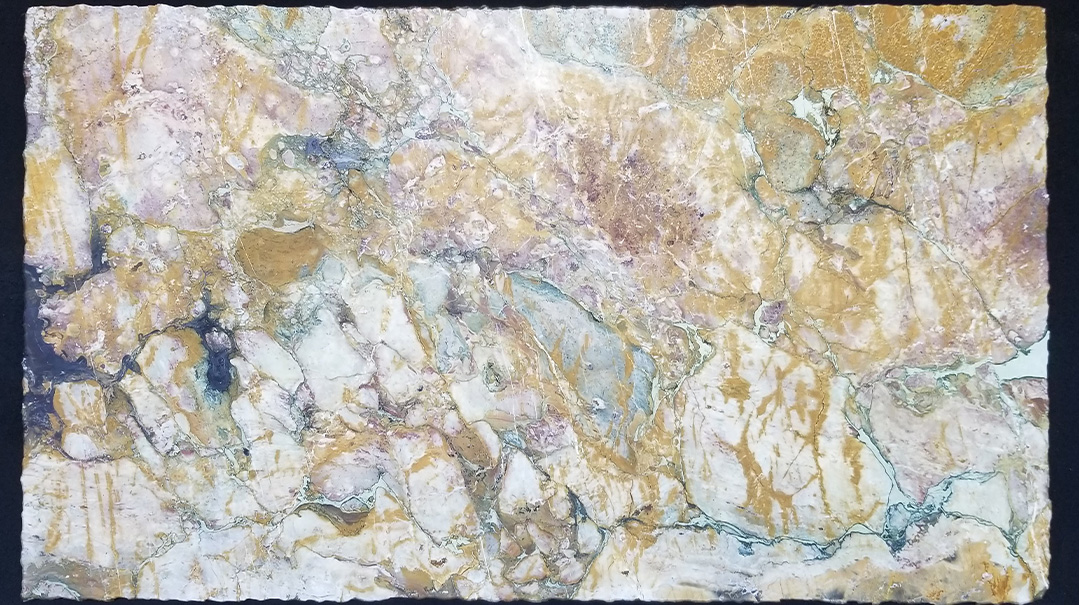

“Benediction,” a celebration of blessings and abundance, started off as a hidden image embedded on a slab of marble

Sharing the Bounty

One of ALMA’s most well-known pieces is a massive 104-inch by 60-inch slab of French Brèche de Vendôme marble titled Bènèdiction, currently on display in Long Branch, New Jersey’s Salt Steakhouse. It depicts a group of people bearing baskets of fruit being brought as bikurim to the Beis Hamikdash and reflects on elevating blessings and abundance by sharing with others. The scene shifts from sharper focus to a more abstract rendering as light from an unobtrusive ceiling projector slowly waxes and wanes.

“People don’t always see it immediately,” says Zelingold. “Usually when they get to the end of their meal and are less focused on food, they move over, get engaged and start a conversation about it. You’ll always find visitors or passersby on the street, from where it’s clearly visible at night, talking about Bènèdiction, taking selfies with it, and filming the transition as the lights fade in and out.”

Bènèdiction was commissioned for Salt, whose designers wanted a stone with a desert-colored palette that worked well with the restaurant’s decor. After locating yards that stocked Brèche de Vendôme, the ALMA team went to look at various slabs of the exotic marble, waiting for something to pop.

“Our team was trained by Jéda to develop the eye to identify potential art and look at it from the macro, the micro, from this angle and that angle, even upside down and often using VR glasses,” says Zelingold. “They sit there and squint and turn their heads zooming and panning, and then all of a sudden, we have that eureka moment.”

In its original state, the slab that ultimately became Bènèdiction weighed in at 1,000 pounds. But like most of ALMA’s larger pieces, a special finishing process made Bènèdiction infinitely more mountable, diminishing its weight by approximately 60 percent.

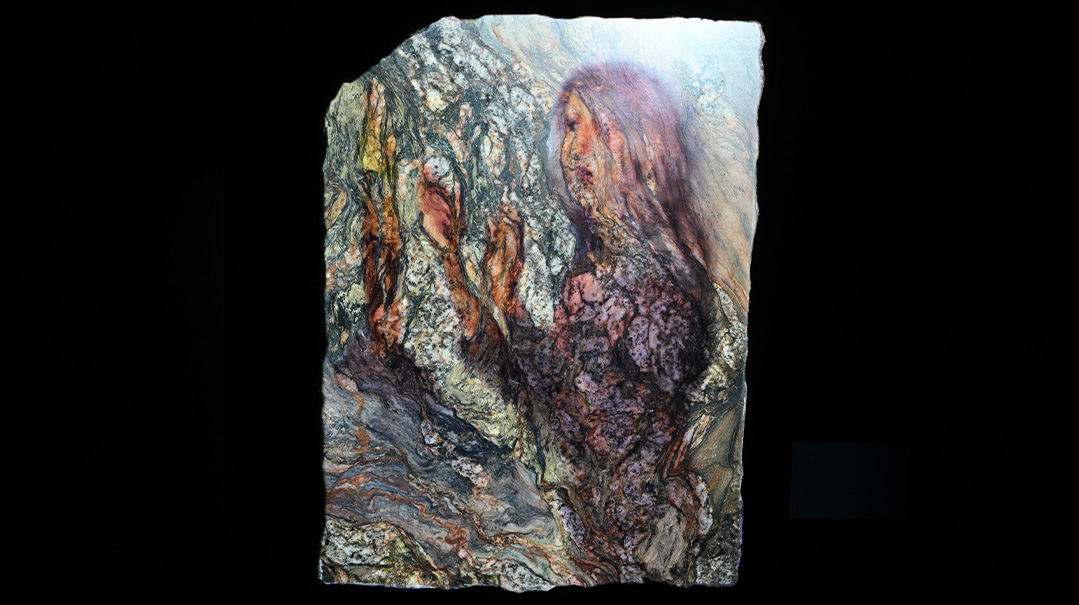

When Jeda tilted his head, the image of “Eve” was clear

Face in the Grain

It should come as no surprise that art as rare and as labor-intensive as the pieces in ALMA’s gallery commands premium prices. Prices for ALMA’s current collection range from $79,000 to just under $500,000 but, ironically, the smallest piece in the ALMA gallery is also the priciest, a 29-inch by 21-inch slab of Fusion Wow quartzite titled Eve.

An exceptionally detailed image, Eve portrays a shawled woman waving her hands delicately over what Jéda sees as the flickering flames of a pair of Shabbos candles. While some ALMA Art is more abstract and suggests outlines and figures, it isn’t hard to see the shape of a nose, eyes, a mouth, bent elbows and curved fingers even in Eve’s natural state. Those many intricacies and nuances, as well as its smaller size, made Eve a more challenging piece to develop.

“The delicate grace and poetry of the story and the way it lives within the stone, as well as the paradox of such profound detail that was also so hidden, epitomizes the speciality of ALMA like no other work we have as of yet, and people respond to it with unique passion,” says Zelingold. “Eve’s perfection and poetry is one of those rare finds within the rare finds.”

Eve’s distinctiveness also manifested itself in other ways. It’s the second of two pieces that came from a single slab of quartzite, the first a scene depicting the conflict of emotional pain and joy titled Saudade, which translates to melancholy in Portuguese. One day Jéda tilted his head to the side while staring at the still uncut Saudade lying against the wall and suddenly realized he was seeing something else.

“All of a sudden, he jumped like he’d been bitten and was like, wait, you have to see this!” recalls Zelingold.

Eve is also one of several irregularly shaped ALMA pieces, with an upper left corner that appears to be missing, but really isn’t at all.

“We didn’t choose to have that,” says Zelingold. “We saw the picture in the slab but the stone ended right there and this is how it came out when we cut the image out of the stone. At first, we were bothered by it, but this is natural and just adds so much to its grace.”

While one image of the twin stones seems to be a violent protest, its facing image is a sofer bent over a scroll, quill in hand

Two Sides of a Slab

Given that slabs of stone are cut off a mountain much like the way we slice a loaf of bread, it stands to reason that if one slab has veining that tells a story, there is a possibility that an adjacent section might also contain similar images. Whenever Zelingold and Jéda find a stone that meets their needs, they inquire about availability of any neighboring slabs, in the hopes that one of them might hold a duplicate scene. More often than not, the change in veining between slabs ruins any possibility of finding a match, and to date, the ALMA team has found just two matching sets, with workable images depicted on the facing stones. Both are cut from Italian Arabascato Orobico marble — an edgier piece titled Dissent speaks to the nature of protest and war, while the second, titled Eternity, shows a sofer bent over a sefer Torah, quill in hand.

“We felt like lightning struck twice,” says Zelingold.

The two slabs of Eternity have both been sold to collectors and are near mirror images that measure 31 inches by 56 inches. As with many pieces of ALMA art, Zelingold sees an inherent element of contrast in Eternity.

“The concept of Torah is one of life, while stone is inanimate,” explains Zelingold. “The dichotomy here is that the story of life is actually petrified in stone. Dichotomy is a theme that intrigues us and we look for it.”

The two sets of twin slabs — Eternity and Dissent — also reflect another reality for ALMA. While Eternity captures a timeless scene that is fundamental to Yiddishkeit, Dissent has an appeal that transcends the Jewish market.

“The fact that we’re Jewish does have us seeing things that are engraved in our brains and close to our hearts, but ultimately, the art is whatever story the stone is telling,” notes Zelingold.

Sometimes you need colored filters and digital light overlays to open your eyes to the beauty within the stone

No Stone Unturned

Locating a stone with artistic potential is akin to finding a needle in the proverbial haystack. Over the years, Jéda and Zelingold have found that slabs with intense non-linear veining are more likely to have a story, with the presence of minerals, opacity, and contrasting colors and shades also increasing the odds that a stone could have serious potential.

“The beauty of a stone is one of the first elements that we consider,” explains Jéda. “You can find an ugly stone that has a story but that’s not what someone is going to put up in their home, in a museum, at the airport or in a hotel lobby.”

Though they’ve traveled to Europe and beyond in their search for slabs, being located in the Tristate area brings with it certain advantages. Jéda and Zelingold have plenty of local stone yards to scour in their never-ending quest for their next masterpiece, generally avoiding the more common images of natural landscapes, forests or mountains, which lack the fundamental “wow” factor that gives ALMA pieces their characteristic appeal. In cases where clients request a specific material, Jéda and Zelingold call vendors for pictures of the requested item, examining piece by piece, slab by slab, waiting for the stone, as Jéda says, “to talk to us.”

“Other times, we go down to the stone yard and look,” says Jéda. “They know by now that we are the crazy guys who sit there squinting and looking at every possible angle until we find something.”

Dealing with oftentimes large slabs of stone obviously presents certain challenges. While the ALMA team uses specialized hand trucks and suction devices to move some of its smaller pieces around in the studio, larger and heavier slabs have to be moved professionally.

Currently, the ALMA team uses quartzite most often, and Jéda and Zelingold have their favorites. Fusion quartzite, which comes in a wide variety of colors, has long been a perennial pick because of the wild nature of its veining and the dynamics created by its multiple layers of elements and colors. The duo also professes a love for the beauty and graceful intensity of Blue Louise, another quartzite, although a recent find that is exclusive to a Brazilian quarry may snag the top spot on their list of preferred stones.

A Global Audience

Understanding the importance of networking and sharing their product far beyond their own reach, Jéda and Zelingold managed to arrange a meeting with the undisputed leader of the natural stone world, Alberto Antolini. It wasn’t lost on the pair that they would be lucky to get 10 minutes of the stone magnate’s time and they were warned to expect him to be on the phone for at least five of them. Jéda and Zelingold arrived in Antolini’s Verona, Italy headquarters bearing a stone mezuzah case and a Hebrew-lettered parchment tucked inside, explaining that the mezuzah was a personal gift from the ALMA team.

“It isn’t easy bringing a meaningful present to someone who has it all, but it was obvious that he was touched,” observes Zelingold. “We told him that the letters had been written by a scribe and then showed him Eternity and its image of a sofer writing a sefer Torah, feather and quill in hand. He went crazy and sat with us for two hours, ignoring all of his phone calls.”

Antolini was so impressed by ALMA’s vision of seeing stone as art that he spoke with Jéda and Zelingold about highlighting their work at Marmomac, the world’s largest natural stone show, held each year in Verona, Italy. While the conversation evolved into a discussion of what a potential booth might look like, Marmomac is currently held each year during the Tishrei Yamim Tovim, making an appearance by the ALMA team anything but simple.

Another high-end market encounter went equally well several months ago when Zelingold found himself in a newly opened Gucci store in Burj Al Arab, a seven-star hotel in Dubai. Gucci’s head of marketing was in the store, and deciding to go for broke, Zeilingold shared the ALMA concept with the company rep.

“He told me that he had been planning a party with a million-dollar budget and he wanted something unique for the event,” says Zelingold. “The party had already happened, but he said that what we had was unique and special and told me to be ready for his next party.”

Closer to home, ALMA’s works are currently under consideration for several Madison Avenue-level projects in competition with well-known and established artists whose pieces sell in the tens of millions of dollars, an impressive feat for a gallery whose works were introduced to the public less than a year ago.

ALMA director Jay Zelingold. As they visit stone yards, staring at slabs and waiting for images to emerge, the possibilities are endless

Hidden Lights

Perhaps one of the most unusual aspects of ALMA’s art is its ability to transform a seemingly mundane chunk of rock into a breathtaking showpiece. The allure of reimagining the utility of a commonly used item is hard to resist.

“When we met with Alberto Antolini, he told us that he loved the idea that we were taking stone that until now might have been used for a wall or a floor, or even as something that could be used to cut tomatoes and peppers, and elevating it to a work of art, made completely out of nature,” says Zelingold. “He loved that we were seizing on its untapped potential and turning it into something that people would appreciate and value in an entirely new way.”

Having spent many an evening in Salt watching people engage with Bènèdiction, Jéda and Zelingold have seen for themselves how diners become excited by the novelty of seeing stone in, literally, a whole new light.

“We are all familiar with marble, granite, quartzite and onyx, but we all associate it with surface-level elegance that adds accent to a space,” explains Zelingold. “ALMA flips that notion on its head and opens the viewer’s eyes to a world within that which he or she already thought they knew and understood. Additionally, the sheer preposterousness that a million tiny random streaks of nature could have actually fallen together in the perfect form to create intricate art that is so profound and beautiful is absolutely mind-boggling and captivating.”

“People appreciate art as epitomizing niflaos ha’ish, but it’s not,” adds Jéda. “Art is always essentially niflaos haBorei and an ALMA work shifts the awe away from the artist and over to the Borei Olam in an extremely powerful way.

Remains to Be Seen

Currently, ALMA has 12 pieces are up for sale, with several more in various stages of development, a process that can take four to six months from start to finish. Its finished products have a broad appeal, with some responding to images whose themes resonate strongly with them, while others are drawn in by the general appeal of artwork that is taken straight from nature.

“This is untouched by human hands,” notes Zelingold. “It is the oldest art in the world reimagined with the metaphysical properties of light. When we take clients to Salt and see how people react to an ALMA, they feel like they are getting an unsurpassed conversation piece, something that other people don’t have and that can’t possibly be replicated.”

Seeing people connect with their artwork is extremely gratifying for the ALMA team, who have already witnessed how once people’s eyes are opened to the beauty within stone, they view the medium in a completely different way and delight in the discovery of hidden gems. Interest in ALMA’s artwork has been growing steadily since Jéda and Zelingold went public with their vision nearly a year ago, and the possibilities appear to be endless as they continue their vigils at stone yards, staring at slabs and waiting for images to emerge.

“I challenge people to find anything more unique than this,” says Zelingold. “What we’re doing is different and interesting and, to the best of our knowledge, it isn’t being done anywhere else in the world. Most incredible of all is that this is essentially the world’s oldest art, something that has been around since Creation and is just waiting to be discovered.”

For more information on ALMA Art, contact Mishpacha.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 924)

Oops! We could not locate your form.