Sefer Sleuth

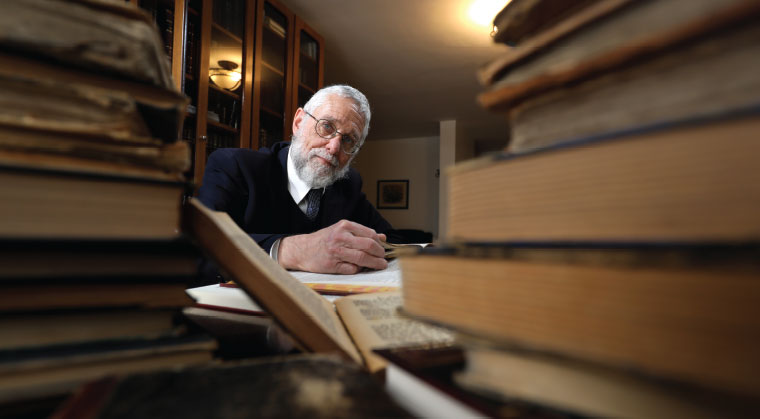

Photos: Eli Cobin

Thursday night in Jerusalem is always hectic —but this one was particularly so for Rabbi Yaakov Rosenes. Two large orders had come into his seforim website: Dvir in Raanana wanted 12 volumes of Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv’s he’aros, along with the last three volumes of his Sh’eilos U’Tshuvos; and Jeff in New Jersey was seeking the 18-volume Tiferes Tzion by Rav Yitzchak Zev Yadler.

Google often lists Rabbi Rosenes’s website, Virtual Geula, among its top results for Torah literature title searches, offering hope to seforim hunters like Dvir and Jeff who have exhausted every other possibility. Rabbi Rosenes has built an extensive list of contacts and seforim purveyors over the years; for Dvir and Jeff, he knew exactly where to turn.

Rabbi Rosenes set out from his home office in Ramat Shlomo in the family car. The first pick-up — Rav Elyashiv’s seforim, for Dvir — took Rabbi Rosenes to the old part of Givat Shaul, the home of Rav Chaim Zeivald. Rav Zeivald was the editor for most of Rav Elyashiv’s seforim, and a formidable talmid chacham in his own right. The particular volumes that Dvir in Raanana wanted were nearly impossible to find in stores. Rabbi Rosenes knew that Rav Zeivald was the world’s sole source for these works.

The door to the Zeivald home opened and the rich aromas of Erev Shabbos wafted out. Rebbetzin Zeivald explained that the rav was at the beis medrash, but she invited Rabbi Rosenes in to take the seforim while she and her daughters continued with preparations. He surveyed the 1950s décor in the salon and made his way around the family table, at that moment serving as a staging area for baked goods.

Stepping around baskets of clean laundry and grandchildren’s toys, he arrived at the tall bookcases, where Rav Zeivald had prepared the order. Most of it, that is — a few stray items had to be located at the top of the packed shelves. A chair was provisioned for him to climb on to reach the last volumes. Rabbi Rosenes collected the box of simple black books containing Rav Elyashiv’s treasured divrei Torah and left for his next pick-up — in the cozy back alleys of Beis Yisrael, near Yeshivas Mir.

Jeff in New Jersey had ordered Rav Yitzhak Zev Yadler’s sefer Tiferes Tzion, an 18-volume commentary on Midrash Rabbah with mind-boggling breadth, depth, and associative leaps. Rav Yadler (1843–1917) was a talmid chaver of the Maharil Diskin and father of the Yerushalmi Maggid, Rav Ben Tzion Yadler. In Rav Yadler’s time, obtaining bread took precedence over pen, ink, and paper, much less printing a sefer; the edition that Jeff sought was actually printed by a son-in-law of Rav Yadler in 1960, and it is sold today only at the home of a descendant named Goldman in the Beis Yisrael neighborhood.

Arriving in the winding maze of narrow, winding streets, Rabbi Rosenes parked his car and set out on foot searching among the unmarked buildings. He asked a passing Yerushalmi bochur where the Goldmans lived; the bochur turned out to be a Goldman himself and directed him to the house. Rabbi Goldman greeted Rabbi Rosenes warmly at the door of a humble abode whose simple furnishings probably antedated the Zeivalds’ by 75 years.

Rabbi Rosenes was invited in, and there followed a discussion over Rabbi Goldman’s relation to the Yadler clan (he was a great-great-grandson of the mechaber). Then, since Rabbi Rosenes was buying the very last copies of Tiferes Tzion from the first printing 58 years earlier, Rabbi Goldman asked about reprinting the sefer. Rabbi Rosenes assured him he would look into the options and, bidding the Goldmans a good Shabbos, he lugged the massive set back to his car.

Global Reach

Rabbi Yaakov Rosenes calls his livelihood the “weird profession of book-finding.” But he really serves as a bridge between two worlds: denizens of the 21st-century searching the Internet for rare or out-of-print Jewish books and all the talmidei chachamim and Old World seforim sellers who live “off the grid.” The Virtual Geula website aims to be as comprehensive a bibliography of the world of Torah literature as exists anywhere; the homepage promises visitors the service will enable them to acquire “any sefer that has ever been printed, as a new, used, or facsimile copy.” But the website is only the front end of the service; behind it stands the expertise and experience of Rabbi Rosenes, built over four decades. His network of contacts reaches into every Israeli boidem and machsan that warehouses books.

“You do this for 40 years, you start to figure out the connections,” Rabbi Rosenes says. “I’ve been dealing with books since 1975.”

He doesn’t maintain any inventory himself, stressing that he is not running a retail outlet but rather providing a service.

“When it comes down to it, I don’t want to have stock,” he says. “I don’t want to be a person who’s running a seforim store all day. I want to be your shaliach, your bibliographer — I’m going to create a dedicated search on your behalf. I love helping people find a book that exists only in the author’s hands.” d

He runs the website as a business, charging for his services and offering memberships for his most frequent customers. He has an immediate goal of cataloguing at least 10,000 in-demand seforim so that self-publishing authors and collectors can meet Torah students and researchers on his website. One regular buyer is the gabbai seforim for Yeshivat Ateret Kohanim, whose rosh yeshivah is Rabbi Shlomo Aviner — “He’s really into Hungarian poskim from 100 years ago,” says Rabbi Rosenes. Another frequent flyer is a ger tzedek in Paris always looking for hard-to-find Kabbalah seforim, and still another is a physics professor who previously worked in the US nuclear weapons development facilities in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

“He’s been very successful at finding what I need,” says Rabbi Reuven Axelrod, a talmid chacham from Har Nof, Jerusalem, and a loyal customer of Rabbi Rosenes for 15 years. Rabbi Axelrod — who Rabbi Rosenes says is an original talmid of Rav Aharon Kotler in Lakewood —places his orders the old-fashioned way, by phone. “I’m not into websites. I don’t even know how to turn on a computer.

“His service has been very useful. The seforim I’m looking for — mainly lomdishe seforim, sh’eilos u’teshuvos — are not around in stores at all.”

“I met Yaakov Rosenes through my customers,” says Israel Mizrahi, owner of Mizrahi Book Store in Flatbush, Brooklyn. “He and I deal with the same people. I send him referrals, and he sends me referrals. We have 180,000 books here in our store. But nine out ten titles I get asked for, I don’t have in stock. What he’s trying to do is fill that gap.”

“He fills an important role in cataloguing seforim,” agrees Dr. Mordechai Tobias of Kollel Yad Shaul in Johannesburg. “He’s positioned between the smallest publishers and the biggest players, in that environment in between, connecting all of them.”

Fortuitous Connections

All this is a long way from Ottawa, Canada, where Yaakov Rosenes came into the world 68 years ago. Born into a Conservative family, at university he became a philosophy major. Rabbi Yaakov Schechter, the campus Hillel rabbi, introduced Rosenes to the writings of German baal teshuvah philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, whetting his appetite for Yiddishkeit. After he later got a recommendation to go to Eretz Yisrael and learn at the Hartman Institute, Rosenes was sent to a chareidi family in Mattersdorf for Shabbos. Fifteen minutes in, overwhelmed by the peace and calm that enveloped the neighborhood, young Yaakov knew he had found what he was looking for.

He went on to learn at Yeshivas ITRI, forming a lifelong bond with Rav Shlomo Fisher, one of the roshei yeshivah; and in Moshav Tifrach in in the Negev. He formed two connections to Jerusalem’s illustrious Farbstein family: the Hevron rosh yeshivah, Rav Avraham Farbstein, and the rosh yeshivah’s cousin, Pnina — whom Yaakov would go on to marry, with Rav Farbstein serving as mesader kiddushin. Reb Yaakov learned in the Mir and the kollel of Rav Yisroel Zev Gustman. Other fortuitous connections came along when Rabbi Rosenes had the opportunity to serve as a driver for such personages as Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Rav Shlomo Wolbe, Rav Chaim Kreisworth, Rav Ephraim Greenblatt, and several famous rebbetzins. Through his wife’s family, Reb Yaakov also got to know Rav Refoel Shmulevitz, who was also a formative influence.

“He personally worried about getting my kids married,” Rabbi Rosenes says. And he was successful with all ten.

Microfiching Expedition

Rabbi Rosenes’s entry to the world of seforim came with a job at Feldheim Publishing. From the job at Feldheim, with a connection through Rav Farbstein, Rabbi Rosenes landed a position at Yad Harav Herzog, which publishes the Encyclopedia Talmudit. Rabbi Yehoshua Hutner, the director of the encyclopedia, tabbed Rabbi Rosenes to acquire rare and out-of-print seforim for the Yad Harav Herzog library. Rosenes’s investigations let him to the Israel National Library, which had a very substantial collection.

In 1986 Rabbi Rosenes was inspired to start up a special archival project involving the National Library of Israel, on the Hebrew University campus. He obtained funds through the Rudman Foundation, and also contacted a Dutch company called IDC that manufactured microfiche equipment. It was a new development, essentially photography that shrank images to very small sizes so that large amounts of printed material could be stored in a compact space —state-of-the-art imaging technology of its day. Rabbi Rosenes raised $20,000 (a large sum then) to purchase a microfiche camera and negotiated with the National Library’s management for access to the seforim. The library head agreed to install the microfiche camera on site so the seforim could be photographed without being taken out of the building.

The program, called the Jewish Archival Project, went swimmingly for several years, continuing even after a library management change. Then one day in the 1990s, on his way into the building, Rabbi Rosenes saw that some yeshivah bochurim had come to avail themselves of a new library resource: the Internet. And they were using it for less than wholesome purposes. Appalled, Rabbi Rosenes wrote an unsigned letter to the Hebrew Yated Ne’eman, warning parents to keep their children away from the National Library.

“But the editor knew me, and knew I had written it, and he put my name on the letter,” Rabbi Rosenes recounts.

Someone brought a copy of the paper with Rabbi Rosenes’s letter to the new library head, a secular lady historian.

“She went through the roof,” Rabbi Rosenes says. “She told me, ‘You and all your equipment are out of here in 24 hours.’ ”

Thus, the rare seforim preservation project at the Israel National Library came to an abrupt end. In the end, however, it worked out for the best. Microfiche was already being surpassed by other technology.

“I ended up selling the camera to an Arab in the Old City for $2,000,” Rabbi Rosenes says with a laugh.

And the experience impelled him to check into this new phenomenon of the Internet. Which ended up taking his interest in seforim preservation in a most fateful direction.

Google Is a Golem

At a wedding some years ago, Rabbi Rosenes asked his rosh yeshivah from ITRI, Rav Shlomo Fisher, if computers are not a “maaseh Satan,” something created for the service of evil. Rav Fisher’s answer shocked him.

“There is no such thing as a maaseh Satan,” Rav Fisher replied. “Computers and cell phones and Internet and all of the technology that is driving the world towards distraction are all only a golem. If we choose to use it for good, Hashem helps us. And if we choose to use it for bad, Hashem helps us.”

This confirmed Rabbi Rosenes in his thinking that technology could be put to the service of Torah. “Google loves , because we have so much material up there,” he says now. “And Gmail is my primary means of communication.”

It was through Google and Gmail that Rabbi Rosenes formed a connection with Dr. Mordechai Tobias of Kollel Yad Shaul in Johannesburg, South Africa. Ten years ago, Dr. Tobias had volunteered to reorganize the kollel’s otzar haseforim, which was then in disarray — sets were missing volumes, needed titles were lacking, and everything was out of order. Now the collection totals 7,000 works, and a digital catalogue keeps track of where they all are.

“Yaakov Rosenes has become a very important key in this whole process,” says Dr. Tobias. “He’s a real expert in seforim. He’s in touch with all the publishers, and also has a very significant network of used seforim sellers. We found we could source used sets of seforim through him or even order reprints.”

Dr. Tobias says Rabbi Rosenes’s expertise in another area was equally valuable — getting access to outside digital catalogues. Rabbi Rosenes helped the kollel connect to the online databases at the Israel National Library and Bar-Ilan University, as well as Otzar Hachochma — ultimately giving the avreichim digital access to over 150,000 titles. But Dr. Tobias remains most impressed by Rabbi Rosenes’s ability to track down that elusive book that couldn’t be found anywhere else.

“It’s quite amazing,” Dr. Tobias says. “I’d contact him about a sefer long out of print, and then three weeks later I’d get a notice that the sefer was on its way to me, from somewhere in France or the States. The avreichim in the kollel were often as surprised as I was. He’d be able to source a sefer that had been out of print for 30 years.”

He has also asked Rabbi Rosenes — whom he now calls “a close friend” — for help with his personal searches. “I once found a sefer in Eretz Yisrael, only one volume out of a set called Bircas Yitzchak, by Rav Yitzchak Farkasz. He was a mohel and shochet in Eretz Yisrael who had lost his entire family in the Holocaust. He left his notes of divrei Torah to be published after his death – it was all he had in the world.

“It was a very rare sefer. I contacted Yaakov Rosenes about it, and to my amazement the set was soon on its way to me. It’s my favorite sefer, I learn from it every week.”

Paying It Forward in Panama

There was another sefer, though, that almost got away. Rabbi Rosenes recalls the tale, which stretched over two decades and involved three separate encounters with the same sefer.

While Rabbi Rosenes was working at Yad Harav Herzog, its senior librarian, Rav David Dravkin, was researching a sefer titled Tzeidah L’derech, a multivolume code of halachah by Rav Menachem ben Aharon Ibn Zerach, an important Rishon in Spain who lived after the Rambam and before the Beis Yosef. The sefer was cited many times in other halachic works, but had itself only been printed twice in 500 years. Rav Dravkin asked for Rabbi Rosenes’s help in preparing a new edition for print. A great deal of work went into it, but they were not able to complete the project before Rabbi Rosenes left Yad Harav Herzog. Later, after Yad Harav Herzog’s director, Rabbi Yehoshua Hutner, was niftar, Rabbi Rosenes feared all their work on the sefer was lost completely.

Fast-forward ten years. Rav Tzion Levi, the beloved Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Panama who was niftar eight years ago at the age of 83, dispatched some members of his kehillah to Rabbi Rosenes to ask his help in locating an edition of Tzeidah L’derech. Rav Levi remembered learning the sefer in a beis medrash in Yerushalayim 65 to 70 years earlier, staying up all night with it until he had committed it to memory. But now he wanted a copy of the sefer. Alas, Rav Dravkin’s edition had never seen the light of day, so Rabbi Rosenes set about making a copy of the first printing for the Rav. But when this copy was sent to him, the Rav could not recognize this Tzeidah L’derech as the same sefer he had read as a young man.

Fifteen years later, Rabbi Rosenes heard that the first volumes of a new edition from Rav Rami Yuniav of Tel Aviv had started to appear. Rabbi Rosenes contacted Rav Yuniav to wish him hatzlachah and tell him the sad story of Rav Dravkin’s unpublished manuscript.

“Rav Yuniav told me that one of the editors of Yad Harav Herzog had rescued it and mailed it to him to incorporate it in his new edition – which indeed he is doing,” Rabbi Rosenes says.

In the end, the request carried over from Panama was fulfilled.

Whither the Book?

Despite the encroachment of the Internet on our attention spans, and the profusion of scanned PDF files substituting for bound, published books, Rabbi Rosenes sees ample reason to be optimistic for the future of his chosen line of work.

“The Internet is an amazing tool to find information about books. It is not at all a replacement for books,” he says. “Some people are fine with just printing out the scans, but some people want to Study the original document. There are still many, many people looking for the actual books.”

Israel Mizrahi concurs. “Books offer a window to a different world,” he says. “Jews have an obsession with keeping our past, and that past is often found only in seforim. The old towns in Europe all had printing presses. After the Churban, the only remnants of many of those places are the seforim that were published there.

“I recently saw a copy of the sefer Bnei Yissaschar, in which a person in Hungary before the war had inscribed a hope that he would merit to learn the sefer. The whole town was killed two weeks later – but the book survived.”

Sometimes, he says, a book is the only connection for a customer to the family he lost. “I’ve found books for people that were written by their ancestors who had been killed by the Nazis. When I’m able to present people with the sefer written by their ancestors who died al kiddush Hashem, they often cry.”

“Seforim are important not just for sentimentality,” Rabbi Rosenes clarifies. “Rav Hutner used to comment, ‘Otiot machkimot.’ Look inside! Yes, Inside! It is not the same as a computer screen! Computers are for data. Seforim are for learning Torah. Even the secular world is going back to books because they are uniquely engineered for human association, reflection, contemplation and memory.”

Ultimately, it is that human connection that books provide that keeps Yaakov Rosenes in his “weird profession.” “I want to keep this business going,” he enthuses. “I want to be someone who supplies information to the Torah world.”

That same drive is what draws his customers.

“He also brings a nice, personal touch to his work,” says Dr. Tobias. “At the end of the day, there is a personality behind all of it — the dedication to tracking down seforim, spending his precious hours in the evening. He provides a tremendous service to the seforim-reading public. We’re very privileged to have him.”

Author, Publish Thyself

Technology has revolutionized the publishing industry, perhaps more than Gutenberg’s famous printing press of 500 years ago. Someone wanting to publish a sefer these days faces much lower obstacles than authors did twenty years ago. The Torah world, Rabbi Rosenes points out, is not immune.

“Look around any beis medrash,” he notes. “How many yungeleit using laptops do you see? Chances are the beis medrash has more computers than it has electrical outlets to recharge them. And all of these avreichim are writing seforim.”

Rabbi Rosenes fears the burgeoning seforim supply from self-publishing will greatly outstrip reader demand. “One bookstore owner told me when he sees an author coming in the front door with a pile of seforim, he runs out the back door so as not to embarrass him. He doesn’t have shelf space for yet another avreich with yet another sefer.”

Rosenes counsels would-be authors that it’s much easier to commit thoughts to pixels than to pen, and he strongly urges them to consider the downstream effects in the current market glut.

“I have printed my own Sefer in an edition of 30 copies for my children and grandchildren,” he declares. “You need to know who your market is, know what your limitations are, make sure you’re writing something for somebody. Writing a book should be an author’s attempt to connect with his readers. Make sure you’re adding something to Klal Yisael. To every yungerman sitting in beis medrash writing his chiddushim on Bava Kamma – I don’t mind if he prints off fifty copies and learns it with his students and sons. But why crowd the shelves of the beis medrash with more seforim? Because you want your mechutanim to know you’re a mechaber?”

He also adamantly insists that every writer must hire a strong editor. “Even the best writer needs an editor — because you make mistakes, you say things that nobody can understand. People don’t have time to read something they don’t understand. They broke their heads all day on learning a terse comment in the Gra. Why should they break their heads on an unclear statement from Acharonei Acharonim — i.e. you?”

The system of “peer review” by talmidei chachamim that tended to limit the number of seforim being published in days past has largely “broken down,” Rabbi Rosenes laments.

He tells a story that was passed down to him by Rav Gustman. Back during the Old Yishuv, Rav Leib Rashkash, a grandson of the Be’er Hagolah and regarded as one of the geonim of Europe, came to settle in Jerusalem. A chashuve local talmid chacham had written a sefer and came to Rav Leib for a haskamah. Rav Leib told him to come back in three days.

When this talmid chacham inquired three days later as to what Rav Leib thought of his book, Rav Leib opened the sefer to the introduction, placed his finger on two words, and said, “Dos iz an emesdige vort.”

The talmid chacham peered at the two words indicated by Rav Leib: “l’aniyas daati.”

“Now that was peer review!” sums up Rabbi Rosenes.

Israel Mizrahi of Brooklyn offers a similar perspective from the retail side. “As a seforim store owner, I have to avoid the mission to have every book in the store. I just don’t know how to handle it.”

So how does he know which titles to stock? It’s a continual challenge, he says. “You never can tell. I just came across an anonymous pamphlet that looked interesting. I researched it and it turned out it was authored by Rav Aharon Leib Steinman when he was 18 or 19.”

Mizrahi does concede that self-publishing profusion in the Torah world may occasionally lead to a diminution of quality, but says he ultimately sees the positive in it. “If someone spent a year of his life researching and writing a sefer, my feeling is, there’s someone out there who wants to read it.”

For his part, Rabbi Rosenes sees Israel Mizrahi as a sentry in a lonely battle. Many bookstores are cutting back on new seforim and instead offering more Judaica, toys, games, and the like. Rosenes waxes nostalgic about a long-lost bookstore in Meah Shearim called Shtitzburg. “The owner knew every sefer in his store, you could schmooze with him for hours about the mailehs and chisronos of every sefer.”

Nowadays Rabbi Rosenes says he knows of only one bookstore owner like that —Israel Mizrachi. “He knows what’s in the seforim. He’s got the seforim bug much stronger than I do.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 749)

Oops! We could not locate your form.