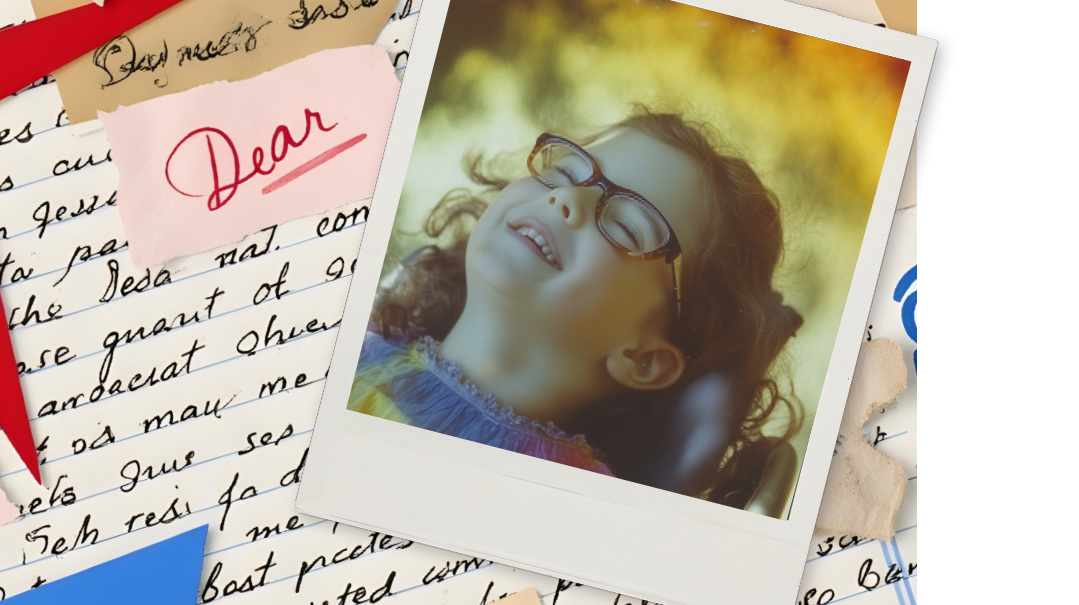

Seeing Color

| September 12, 2023What happened next is vivid in my mind like a scene from a horror film

IN

August of 2018, I began to spiral into a terrifying darkness.

I’d just gotten home from spending two months in a bungalow upstate with my five children, who ranged in age between one and seven. The country had been peaceful, but with my husband coming up only for Shabbos, I’d been busy with my kids nonstop, and lonely without him. I also didn’t have a social outlet because none of the women in the bungalow colony were my age.

Instead of coming home recharged, I felt depleted. And now I had to find a way to stay sane during those hectic weeks between camp ending and school starting. Between nursing the baby, washing dishes, changing diapers, breaking up fights, reading books, folding laundry, and preparing breakfast, second breakfast, snack, lunch, second lunch, snack, and supper… there wasn’t a second to breathe. I was in survival mode, waiting anxiously for each day to end so I could put the kids to bed and have some time to myself.

My husband had just switched from full-time kollel learning to learning half-day and working half-day, and we didn’t have enough money yet to afford the luxury of cleaning help. So on top of keeping my kids fed, entertained, and equipped for the coming school year, I walked around the house with a broom all day sweeping up crumbs, just to create some semblance of cleanliness.

Day after day, I tried my best to stay calm and attentive, to keep it all together. Until eventually… I lost it.

It was at the end of a long day, and I was sitting in the hallway with my kids, helping them change into pajamas and get ready for bed. One of my children turned to me and said, “I wish I had a different mommy.”

If I heard those words today, I would chuckle, knowing the child doesn’t mean it: It’s simply a cry for help or a call for attention. But at that time, the comment felt like a knife in my heart. I was running myself ragged caring for my kids, attending to each of their unique needs, and for what? For them to be ungrateful and throw it all in my face?

When the next three kids chorused along — “Yeah, you’re the worst mommy! We wish we could live with our cousins, and Aunt Toby could be our mother!” — it was too much for me to bear. All I could think was, I’m done! I need out!

What happened next is vivid in my mind like a scene from a horror film.

“You wish you had a better mother?!” I choked. “Fine!”

I ran downstairs with the baby in my arms, opened the back door, and flung the baby at my husband, who was working out back. “They’re yours. Good luck,” I said through tears. “I need to leave.” I raced to my car, driving away with no destination in mind.

I was so hurt and confused. I couldn’t make sense of what was happening with my life. I was raised by good frum parents and had gone to Bais Yaakov, where I was taught to always be good and kind and do what’s right. I was a good girl, a nice wife, friendly with my neighbors, calm with my kids… so why was I struggling so much?

Until that summer, I had felt like a natural at parenting. I have a degree in early childhood education, and I knew just what to do for my babies and toddlers. Suddenly they weren’t so little anymore, and I no longer felt like a pro. My oldest daughter had become incredibly challenging for me, pushing my buttons and blaming me for everything that didn’t go her way.

Where had I gone wrong? What did Hashem want from me?

I drove 15 minutes from my home, parked the car, and started bawling. I was so full of anger, hurt, and frustration. I couldn’t continue living like this, but what could I do? Where could I go?

I thought of driving to my parents’ home a few hours away, but I didn’t want them to think I was a failure. I couldn’t go to any friends — that would be embarrassing. I was too normal to be doing something so crazy. So I just sat there alone in my car for almost two hours, crying hysterically, feeling utterly trapped in my life.

Eventually, I called a good friend of mine who lives in Israel. She sat on the phone with me as I unloaded all my thoughts and feelings, and she heard me without judgment. Because of her validation and genuine understanding of what I was going through, I was able to calm down and recompose myself enough to return home. To this day, I don’t think she realizes what she did for me.

The house was pleasantly quiet when I walked through the door. My husband had managed to put the kids to bed and was sitting at the table learning. I was expecting him to greet me warmly with care and concern — he must have been worried about my whereabouts and well-being. I knew he had been busy with the kids and wasn’t able to call before, but now that I was back and they were asleep, I was hoping he would come to my rescue, offering to do whatever it took to make things easier so I should never feel such helplessness again.

That’s not what happened.

My husband grew up in a broken home, and his parents eventually divorced. When his father left home, he experienced a sense of abandonment. Unfortunately, when I ran out of the house so suddenly, giving no explanation of where I was going or when I’d return, it had reawakened his childhood trauma and fear of abandonment.

He confided that the summer had been taxing on him, too. He’d felt depressed and lonely being home alone all week while I was in the country. He was still recovering from that void… and now this.

That night was a painful low for both of us.

But whereas my husband grew from the experience — he had already been seeing a wonderful therapist and was able to process all his reopened childhood wounds over the next few months — I kept sinking.

Black and White

School started. On the outside, it looked like I was fine. I knew if I didn’t keep up a normal exterior, I’d feel even more worthless and broken than I was already feeling.

Every day, I went through the motions: wake up the kids; get them dressed, fed, and ready for school; go to work and paint a smile on my face; come home and make dinner; do homework and story time; run baths and bedtime. But every step felt burdensome. I felt no joy, not in any of it.

I suddenly didn’t trust myself as a parent. After all, I had almost run out on my own children. I knew someone in my community who had left her family and the father ended up raising the kids. How was I any different? And what if I lost it again? What if I really couldn’t handle motherhood?

I was flooded with anger — both toward myself and my children. I was angry that I didn’t know how to be the perfect mom, meeting everyone’s needs and making sure they were happy. And I was angry at my kids for wearing me out and whining and being ungrateful for all my hard work and nonstop care for them.

I grew up in a home with black-and-white lenses, and it bled into every area of my thinking. For example, if one thing went wrong during the day, I categorized the entire day as bad. If I lost my patience with the kids, I wasn’t a good mother. When my husband had too many l’chayims on Shabbos and got drunk because he was trying to dull the emotional pain he was feeling, all I could think was, How can this be? How can a talmid chacham abuse alcohol? In my mind, things were either black or white — there was no room for gray, or any other color in between.

I began questioning the purpose of my existence. Why did Hashem have to create me? I thought He created us because He is Good and wants us to experience His Goodness. But if I can’t feel any of it, then why create me? I had a deep desire to cease existing. I wanted the earth to just open up and swallow me. Then I wouldn’t feel this depression anymore.

My husband saw I was drowning, and he stepped up to help me. He reassured me that I wasn’t alone in all of this, that he’d always stand by me and have my back. “I’m here for you. We’re in this together,” he’d repeat. He spoke to a noted mechanech and was a different husband after that meeting. He made sure to be around a lot and to help me take care of the kids. He praised my parenting. He told me that since the kids were now older, it was really his job to be mechanech them, so the burden didn’t all fall on me.

When my mind filled with questions that I couldn’t find satisfactory answers to, my husband tried to answer them. He asked his rav, and he gave me seforim to read. He encouraged me to take a popular parenting class and to speak with rabbanim for advice.

With all this hishtadlus, things should have gotten better. But they only grew worse.

I started to fall asleep crying. Life felt so heavy and dark that I’d sometimes start crying when I woke up. Throughout the long day that followed, I fought back tears.

I was suffering on such a deep emotional level that everything I’d learned about nisyonos became meaningless. All I could think was, “Okay, so I’ll get rewards in the Next World for this. Okay, amazing, I’m raising Hashem’s precious gems. But it would have been better had Hashem not created me, because then I wouldn’t have to go through this Gehinnom to get some good that I can’t even comprehend.”

My unresolved questions about good and bad and the purpose of creation circled around and around in my mind in a torturous cycle. I couldn’t break the loop. I wanted to rip out my mind just to make my brain stop.

It reached a point where I couldn’t even make a simple life decision because of the nonstop looping in my mind. I remember one night in particular — I decided I needed to relax, but I couldn’t figure out what I should do. Should I say Tehillim? Rest on the couch? Read a book? My mind circled around between these three choices repeatedly, without stop, until I started crying in frustration.

I didn’t tell either of my parents about what was going on. I had too much pride. I broke down to my mother only once, and that was after almost a year of suffering. It was Erev Shavuos, and I called my mother in hysterics because it was getting close to yuntiff and all I had managed to do the whole day, aside from feeding, bathing, and cleaning up after the kids, was start making a cholent.

I’d peel a potato and then someone needed me. I’d cut an onion, then someone needed me. It was almost time to bentsh licht, and I hadn’t even put in the spices! To top it all off, my friend who was supposed to bring me a lasagna had called to tell me she was so sorry, but she forgot to drop it off and she was already out of state with it in her car. That’s when I lost it and called my mother sobbing. But even then, I didn’t reveal what was really going on.

Month after agonizing month passed like this, until Rosh Hashanah approached. Whereas in previous years, I’d davened to Hashem for a year of health and happiness, that year I cried bitterly asking Hashem to take me. I could no longer handle the torturous thoughts and heaviness of my depression.

Finding Light

My tears must have pierced the Heavens, because after Rosh Hashanah, Hashem took me out of Gehinnom and granted me life. He ignored the words of my lips and heard the words of my heart.

After the Yamim Noraim, I started seeing a therapist. She was a wonderful shaliach who validated my feelings and helped me work toward recovery. She explained to me that I was experiencing depression along with OCD cyclic thinking. It was a relief to finally understand what was happening with my mind, and I was given antidepressants to help with both symptoms.

Along with the medication, I continued seeing my therapist weekly. With her support, I was able to process the harrowing year I’d been through, starting with the evening that I fled from my house. She helped me see that even though I had run away, I had come back.

We talked about why I didn’t reach out to my parents for help. I discovered that in my mind, my role is the one who keeps the family together, so I don’t allow myself to be a source of stress to my parents. With my therapist’s help, I finally opened up to my mother and father.

We spent many sessions working on the black-and-white thinking that pervaded my worldview and triggered my OCD symptoms. I learned how to look at myself and others through a new perspective. People’s actions are not all good or all bad, all nice or all mean. People don’t always have a choice about the way they’re feeling, and the way they deal with things can be for any of a million different reasons.

Although I was healing, I still had many questions about the purpose of life. I kept searching for answers, and one day, I saw an ad in a magazine for a Sod Ha’adam course by Rebbetzin Tzivi Tukachinksy.

Even though I was raised frum, the Torah concepts she shared felt almost revolutionary to me. I grew up thinking that my worth was based on my actions and how well I serve Hashem. She taught that we are Hashem’s children, and He loves us more than we can imagine just because we are His and not for what we do. I have inherent value, even when I make mistakes, even with my flaws.

I had to do a lot of emotional work to internalize this, but when I did, I started seeing life in a new light. It doesn’t matter if I am accomplishing things or if I lost my patience today. That doesn’t define me. Being a Yid, a pure neshamah, defines me.

Through Rebbetzin Tukachinksy’s classes, I began to see negativity as pain, not as a character flaw. My kids are acting like this because they’re in pain. I am acting like this because I’m in pain. Instead of judging my husband when he makes mistakes, I try to feel for him, to have compassion for him. When I’m struggling with the kids, I actively work on not being hard on myself, and on understanding my mistakes instead of being swallowed by them.

Rebbetzin Tukachinksy emphasizes that a mother’s mood shouldn’t be affected by her children’s moods. I don’t have to solve their every problem or address every upset feeling. This concept liberated me. My daughter is throwing a tantrum because she hates supper? Okay, it doesn’t mean I have to fall apart. I look at her with compassion — she’s crying because she’s tired, hungry, and wants attention. I’m still going to serve the dinner I cooked because that works for me, and she’ll be fine. I’m not going to try to solve her problem by making new food or by convincing her the meal is delicious. It’s okay for her to be sad now. My kids are much calmer and solve their problems far more easily when they see I’m not affected by their moods or behavior.

In the past, I viewed evenings as a checklist. Check homework, check supper, check this one in the bath, check this one brushed his teeth, check, check, check, check, next. It was stressful and pressure filled. But that’s not what Hashem wants. Rebbetzin Tukachinksy stresses that Hashem doesn’t want us to just survive, He wants us to live. He wants us to be in the moment, not to just get through it.

Now bath time and bedtime aren’t just a task on my to-do list. I watch the baby play with the water flowing from the faucet and her older sister blowing bubbles. I see the bright bathroom tiles, and I feel the warmth of the water. Even though I’m sticking to the routine, I’m in the moment, taking it all in. I can enjoy all the goodness Hashem is giving me.

I no longer feel the constant pressure to get everything done right, or even done. I understand now that what happens at the end is Hashgachah, and not on me. I go through the same motions I always have — cooking, folding the laundry, sweeping the floor — but with simchah. I’m not stressed; if something doesn’t get done, it’s okay. Hashem has many ways to provide.

I’m relaxed in a real way because I understand Hashem is happy with me no matter what, and He understands how I feel and that this is the best I can do. He’s running the show; I’m just here to provide my heart.

Where I once felt dead, I now feel alive and connected. My life, once black and white, is rich with color.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 860)

Oops! We could not locate your form.