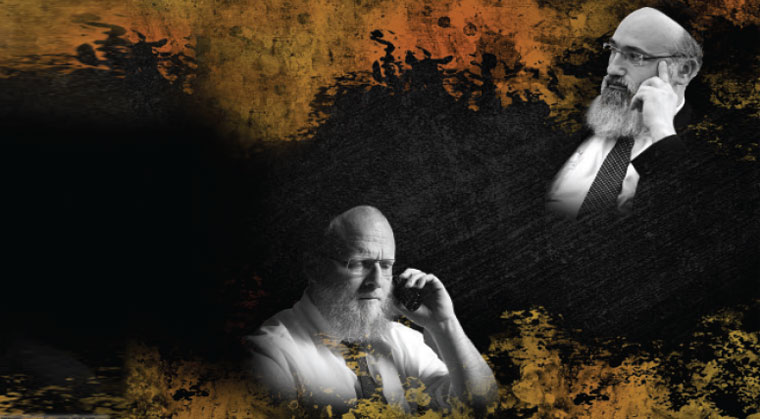

Secret Keepers

A caller to Relief will encounter a warm voice, a guiding hand —and no unwanted questions asked.

Connecting patients and clinicians, the organization has made seeking help for mental health normal.

Behind that revolution stand two men who believed the community could do better.

I

was once at a conference where a respected frum activist got up to speak He scanned the room, the long tables where people were seated row by row, and noticed that in the far corner, two men were deep in conversation.

He grimaced and said, “I can’t begin my remarks while people are talking.”

All eyes followed the speaker to the corner, where Rabbi Binyomin Babad stood whispering with another man. An uncomfortable silence hung over the rented brass lanterns, thick gray tablecloths, and elegant place cards.

Someone seated near me — not the sort to make a public mecha’ah — was visibly upset. He leaned over to the speaker. “If Binyomin Babad is talking to someone, there’s a good chance it’s pikuach nefesh. Leave him alone.”

The term pikuach nefesh sounds weighty, like Rabbi Babad is the sort of person who walks around frowning — edgy, self-important, in full-time crisis-management mode.

In fact, the man holding more secrets than a career intelligence agent, who holds the burdens and worries of so many, looks more like a kindly rebbi on the first day of school — an open face, an easy laugh, and a genial demeanor.

The secret-keeper title makes him smile, though, because it isn’t entirely fantasy. “My father really was in Israel’s intelligence service,” he says. In a career that took him from Eretz Yisrael to Europe and eventually, to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where he worked at Empire Kosher Poultry, Meir Babad did many things. “Some of them we knew about, and others we knew not to ask about. He had secrets.”

Binyomin and Naomi Babad started married life like so many others: They settled in Brooklyn so he could learn at the Mirrer kollel, then moved to Harrisburg, where he joined the poultry business.

As the family grew, the Babads moved to Lakewood, where Binyomin took a position with Agudath Israel’s PCS (Professional Career Services) Division, helping young men train and prepare for entry into the workplace. Through his work in job placement, he established a relationship with an accountant named Sendy Ornstein.

Rabbi Babad was the one charged with spotting talent and jump-starting careers, but things went in reverse.

Because the young accountant had a dream and Binyomin Babad walked right into it.

A

ctivist by nature, Sendy Ornstein was the sort of bochur who visited Brooklyn’s Maimonides Hospital (and, when he learned in the yeshivah in Stamford, that hospital as well) and made himself useful. After marriage, he got busy volunteering alongside Shuki Berman, who was working under medical advocate Rabbi Meilech Firer from Israel. Eventually, the two men established Refuah Resources, a nonprofit group that provides medical referrals, on their own.

It was on the front lines of Refuah — referring, assisting and directing patients to the right doctors and facilities — that he saw the void.

“I remember a young couple from Israel; their first child was born with a heart ailment. They had to sell their new apartment to pay for treatment, and the stress was tremendous. I noticed the mother was suffering. She was clearly depressed and very anxious.”

Reb Sendy had compiled a thick notebook, not just of names of doctors, but also of bikur cholim services, local rabbis, and places to eat near hospitals. He had information on travel times and Hebrew-English translators, but he couldn’t think of a single doctor who could help this woman with her issues.

Not the “someone should” sort of person, Sendy Ornstein began to talk to people in the community about his idea of a medical referral organization for mental health issues. He learned that a Belzer chassid named Shiya Ostreicher had a similar concept.

On a freezing winter night, the two had an unceremonious meeting in a parked car outside of shul. By the time the car doors swung open, there was a vision.

Even if there wasn’t much support.

Sendy smiles. “I remember going to various community leaders to share the concept, and by and large, the sense was there was no need for a formal mental health organization, that the problems weren’t really widespread. But then, after they would politely thank me for coming, each one would inevitably walk me to the door and say, “But if you do hear about a good psychiatrist, I happen to have someone, a neighbor, a friend, a relative, who could use it.”

Armed with the growing conviction that he was on to something, Ornstein had to find himself a name, a base of operations, and someone to run the organization. He also realized that he had his own learning curve to conquer.

“I was in the home of a psychiatrist as he mentioned something about OCD. I asked what OCD was. He looked at me strangely and said, ‘Seriously?’ ”

The doctor came back a moment later with a fat book in his hands. “Here,” he said, handing him the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (known as the DSM), the essential guide to the field. “Read this.”

At a recent dinner, Rabbi Ornstein recalled his early ignorance. “When I started, I had three questions: What’s OCD? What’s DSM? And finally, can the same patient suffer from both OCD and DSM?”

Ignorant, perhaps, but very determined.

For a name, the wife of a potential donor suggested Relief. That just left someone to run the organization.

“I asked Reb Binyomin to join me. I thought he could do a good job.”

Reaching Out, Reaching In

In a second-floor walk-up office in Boro Park sat a plastic folding table, a telephone, and an empty chair.

It was the early days of the organization and the chair belonged to Binyomin Babad, director of Relief. But he wasn’t there.

He and Sendy Ornstein, two dark-suited young men, were circulating at APA (American Psychiatric Association) conferences, working the floor with the persistence of junior insurance salesmen. “What’s your name?” “What’s your specialty?” taking numbers and making notes as they buttonholed clinicians.

The doctors bought into the concept, perhaps seeing the earnestness of these two men, intent on helping their community.

In truth, a respected psychiatrist tells me, it makes perfect sense that the mental health community would embrace Relief and what it offered them. Patients find Relief, who in turn sends them to the right address for help. Success with a patient very much depends on the support network that patient enjoys; in most cases, Relief patients have a family or friends cheering them on.

But the first step is removing the stigma of mental illness and convincing people that help is within reach.

“It was time,” Sendy Ornstein says in a fake dramatic voice, “to open up the can of worms.”

The conference room at Lakewood’s Relief headquarters feels a bit like it could be the BMG coffee room.

The lively discussion on the morning of my visit revolves around the role of media.

Relief succeeded in breaking through, I maintain, because of the blessing of frum media — newspapers, magazines, websites, and finally, private online forums where people who’d been living in lonely agony for so long found comfort in the realization that they weren’t alone.

And also, that they weren’t crazy.

Relief was that invisible magnet that drew them all — the unseen, faceless voices at the other end of the phone, listening closely, then referring them to the in-house caseworker who would chart the course of action.

Dr. Michael Steinhardt, a clinical neuropsychologist, traces the organization’s success and explains how it happened. “It’s virtually impossible for a clinician such as myself to know about all of the professional therapists in every community, each therapist’s specialty, which ones accept insurance, and which clients they work best with,” he says. “Relief took the time to build a reliable and updated base, and even more, to meet with the therapists to whom they refer. They followed up, asking families to provide feedback to them on their experience so that they could help the next family that reaches out to them.”

Mental health became a thing. Conversation in bungalow colony circles and around Yom Tov tables didn’t suddenly grind to a halt if someone mentioned that they were “going for help,” or “seeing someone.”

The chinuch establishment developed new eyes — alert and attentive to any odd behavior or irregularities. Parents made peace that not all issues were disciplinary, and over-opinionated shviggers started to understand that the son-in-law who had trouble keeping a job wasn’t necessarily lazy.

“I knew we’d broken through, that the stigma was gone, when I saw an ad,” Rabbi Babad recalls, “between a promo for a sushi place and a back-to-school shoe sale, for a new therapist.”

That’s the blessing of media — but it’s a mixed bag.

“We’re all for help, for reaching out, for being honest and realizing that it’s no shame to work things out,” says Rabbi Duvi Kessner, director of Relief’s Lakewood office, “but we have something here we call Monday morning BPD. It means that one of the magazines had an article or story over Shabbos about someone suffering from borderline personality disorder, so now everyone is convinced they have it. That’s where media works against us. There’s a certain alarm that results from the fact that you want to sell magazines.”

Rabbi Ornstein enjoys the discussion and debate. He has a diplomatic solution, telling a story about his father, veteran shadchan Rabbi Yisroel Ber Ornstein.

Decades ago, the popular shadchan was walking down a hotel corridor at an Agudah convention when he saw Rav Moshe Feinstein, accompanied by Rabbi Moshe Sherer, coming toward him.

“Rosh Yeshivah,” Rabbi Sherer said, “I want to call this Yid, Rabbi Ornstein, to a din Torah.”

The Agudah leader explained. “He comes here, to our convention, each year, and meets so many families with eligible children, one after another. Then, he makes shidduchim all year long. We should really get a commission!”

Rav Moshe looked at the shadchan. “Nu, what do you say?”

“Rosh Yeshivah,” Rabbi Ornstein said, “Rabbi Sherer doesn’t understand that the only reason many people come to the convention is because I’m here, so he should really be giving me a commission for every guest who joins. They’re all here to make shidduchim with their children.”

Rav Moshe smiled broadly. “Good,” he said, “so each of you should keep what’s yours, in that case.”

“That,” Rabbi Ornstein concludes, “is the relationship between us and the media. You do your thing, we do ours, and let’s both keep at it.”

T

he first point of contact for the client is the receptionist, who simply transfers the call to a caseworker best suited to the needs of the caller.

“We davka don’t want trained clinicians taking those calls and making suggestions, because then there’s a bias to a certain training or discipline,” Rabbi Babad explains. “We have referral specialists with expertise in different areas — children or adults’ issues, anorexia, depression — but they aren’t professional clinicians. They know how to listen and then suggest the right option, recommending the proper specialist and then making the connection.”

When I was about 11 years old and caller ID hadn’t been invented, making prank calls — calling someone and pretending you are someone else — was an acceptable snow-day pastime. It’s been many years, but I’m eager to understand the process from inside. And when I call a random Relief office, I find I haven’t lost the touch.

The receptionist at the upstate New York office asks me when I’ll be available for a call-back from one of their staff. I book a phone appointment with Rabbi Menachem Lowy for 12:30 the following day.

At 12:37 pm, the phone rings.

ML: Hi, I’m calling from Relief.

YB: Hi. Thanks for calling.

ML: How are you today?

YB: Wait, do I have to give my name? Because I won’t.

ML: No, of course not. Many people choose not to.

YB: Okay. I’m not sure I should say this. Or if there’s any point.

(Quiet, reassuring cough by ML)

YB: I feel sort of an anxiety when I travel. I don’t know if I’m crazy, but on days when I travel, I feel like I don’t have a grip, all day long.

ML: Do you travel often?

YB: Yes, I’m in a job that involves frequent travel. And sometimes it’s not for work, it’s with the family.

ML: I would love to travel, seems nice, but it’s causing you trouble?

YB: Very much.

ML: How does that anxiety show itself? What do you do differently?

YB: I make everyone around me crazy. I’m like a control freak. Truth is, I’ve always been a control freak.

ML: (Soft laugh) In what way? Was it a thing that people complained about?

YB: Maybe. I don’t know. No one likes a control freak.

ML: Interesting. I have to tell you that many successful people suffer from anxiety, and they get help and deal with it. They lead very happy lives.

YB: Yeah, but maybe it’s not just anxiety. I make everyone around me miserable, too, when I’m feeling this way.

ML: Really?

YB: Yes. Maybe I’m not just anxious but abusive.

ML: There’s help for all of that, but before we continue, I see you’re calling from a Montreal number. Have you been in touch with our Canadian office? Maybe they know someone in your hometown.

YB: Thank you. I’m calling you.

ML: Okay. So go on, what do you mean abusive?

YB: Like I don’t hit people but I’m not so nice to my family, maybe. I don’t know.

ML: You know that abuse isn’t only physical, and hurting people with words is something that can and should be fixed too, right? So let’s help you. What else?

YB: Sometimes, in airports… food… not so kosher. You know, treif, maybe.

ML: People sometimes do things that don’t fit them in order to run away from a feeling. We have people calling — good, ehrliche Yidden — who do things they are embarrassed of, not out of taavah, but out of pain. Is there anything else that you do because you feel a need to run away?

YB: Why do you want to know?

ML: It would depend on the sort of help we can give you… Anything else?

YB: Yeah. Sometimes I don’t want to be me.

ML: Right, that’s what I mean maybe you do things you aren’t proud of to run away, sort of an escape. Let’s help you face it, okay?”

YB: Are you chassidish? What chassidus?

ML: (Pauses.) I’m a Satmar chassid, why do you ask?

YB: Yeah. Listen. Sorry to waste your time. My name is Besser, I work for Mishpacha, and I really just wanted to see how this all works. The intake process and all that. Sorry to bother you.

(Brief pause, then delighted laughter)

ML: Oh, wow! I love that. What a great idea. Why so short, then, why didn’t you go for longer? It’s so helpful to us to know how we’re perceived from the other side of the line.

YB: Because I feel badly to take you away from others who really need your help, for real emergencies.

ML: I appreciate that. I’m happy to learn that one Yid less has such issues. Tell me, be honest, how did you find this experience?

YB: You were great.

ML: What could we have done better?

YB: I didn’t appreciate that the call came seven minutes later than planned, since I imagine a caller to Relief is in full-on panic mode.

ML: I hear that. What else?

YB: Why ask if I’m Montreal — don’t people want to be anonymous?

ML: I would never do it with a Brooklyn or Lakewood number, but people from out of town deserve to know about help available to them close by. I felt bad for you, especially, to travel unnecessarily, since travel isn’t easy.

YB: I loved that you let me know successful people suffer, let me know that it’s normal, so to speak.

ML: It’s true. We don’t define people by their struggles. But please tell me what you felt I did wrong, we want to get this right.

YB: It felt very right. Compassionate, reliable, and warm, without being too personal.

Just the Right Words

Until this day, both Rabbis Babad and Ornstein, though busy with administration, will also do intake, answering phone calls by themselves.

“When I worked at Empire,” Reb Binyomin recalls, “my father insisted that I spend a few hours a day on the floor, getting blood on my shoes. It’s the only way.”

Rabbi Ornstein, who has never been anything but a volunteer (he’s a CPA who runs his own financial consulting firm), has answered more than 20,000 calls over the years. Still, he readily admits that the staff hired and trained by Relief are better than some of those who’ve been there since the beginning.

“They’re doing this all day,” he says. “We’re busy with funding, with setting up new offices, and they’re just listening to people. They’re great.”

He recalls being stopped by a respected clinician. “You know, I heard about what you do and I wanted to work with you, but I called, just to see how it works, and I wasn’t impressed.”

Stunned, Rabbi Ornstein asked when she’d called — which day, what time, which office.

“When I went back to check the call logs and notes — because we have everything in the system — and I saw the caseworker had written, Caller is too vague, won’t share any information. Something doesn’t add up.”

Calls, many times, don’t come from the sufferer, but from a parent, spouse, or friend.

“But in that area, too, one has to know how to listen closely,” Rabbi Ornstein points out.

Occasionally, a marriage is in trouble because of the negative behavior or personality of one of the parties — but that person refuses to go for help.

“If we get a call from the spouse, once we hear that they’re stuck, maybe their husband or wife refuses to consider help, we make a referral to go see a professional on their own. Aside from the fact that they will get chizuk and learn vital coping skills, what happens is, the spouse will say, ‘If you’re going to talk about me to someone, then I want to be there. You can’t tell my story, I want to,’ and then they end up going together. There’s a real chance they will be helped.”

Are there mistakes? Do the referral specialists ever make a match that doesn’t work?

Rabbi Ornstein is emphatic. “Yes. Getting help is a parshah, and there are many bridges to cross until a patient finds the right clinician. It’s like any shidduch. It needs real siyata d’Shmaya, but we try our best.”

Sometimes, Rabbi Babad says wryly, it doesn’t work for the most bizarre reasons.

He recalls a chassidishe man who met a new clinician. The patient was accompanied by his wife, who was very upset after the appointment. “The doctor was so rude, he called my husband a maniac,” she complained to Rabbi Babad.

Rabbi Babad, who knows the doctor well, didn’t imagine that it could be possible.

“One second,” he said. “Could it be that the doctor said your husband was manic, which is how a clinician might refer to bipolar disorder?”

“Yes, yes, what’s the difference,” she said.

Part of the job is making a match that can work on religious grounds, too.

“Rav Shmuel Auerbach would often call Relief Israel by himself, on behalf of his talmidim. He was very supportive, and he once told me that a clinician doesn’t have to share the patient’s faith to be effective. It’s a luxury, not a necessity,” Rabbi Babad remarks.

Yet, Dr. Steinhardt says, Relief had broken ground in that area, too.

“I have also attended several of their events in New York City, in which they bring together a wide range of clinicians serving the frum community. Among the many benefits of such events, they also utilize that opportunity to educate non-observant and non-Jewish professionals of our cultural and religious sensitivities, since it’s essential for clinicians to be aware of those realities.”

T

here’s a reason clinicians want to be part of the Relief network, and it’s not just because of the higher success rate that results from a supportive network for patients.

Rabbi Ornstein learned a rule from Rabbi Meilech Firer. “Relief does not negotiate with clinicians for lower rates, even if it means that we have to kick in money to help out, because we like to keep favors for when we need a doctor on a Motzaei Shabbos,” Rabbi Ornstein explains. “If a doctor is raising prices unfairly, we might challenge that, but otherwise, we respect their rates. In our community, a middle-class family will spend like rich people when it comes to helping one of the children, and the doctors know and appreciate that.”

Relief’s budget, including payroll for the worldwide staff of about 25 people, is completely donor funded, but there are good Jews who earmark funds specifically to provide access to better quality help for those who otherwise couldn’t access it.

Recently, a desperate husband called Relief because his pregnant wife, upon the direction of her OB-GYN, refused to take medication she needed. “I reached a top psychiatrist who specializes in women’s hormonal issues on her cell phone — she was away on vacation — and asked her to speak to the woman. The doctor called and told her, ‘Your anxiety is doing much more damage to the baby than the pills, which are harmless.’ She saved that family, and that doctor did it happily, because all year long, we send the sort of patients every doctor wants.”

In my industry, the frum fixation on anonymity is seen in the way letters to the editor come with desperate requests not to include names or other details. But in their world, secrecy is everything.

“We’ve had long, involved relationships with people without ever hearing a name. We get that. I always tell the staff that the only executable offense here is loose lips,” says Rabbi Babad.

A close friend of Rabbi Babad reinforces the point. “Binyomin shows nothing. There are people who keep secrets, but you can see them exploding with the weight of what they know. We ask him major questions and he looks as if he’s being asked where the nearest gas station is: always calm, always levelheaded.”

“It’s clich? to say ‘don’t judge,’ ” Rabbi Babad says, “but we get reminders, all day, every day. We live it.”

It takes a great man to admit that, Rabbi Ornstein says — and tells a story of a great man who did.

It was at a Relief-hosted event for mechanchim, and the Rosh Yeshivah Rav Chaim Epstein ztz”l spoke. He told the story of a bochur in his yeshivah who seemed inordinately fretful and neurotic.

“But in those days, who knew of OCD?” the Rosh Yeshivah cried out, his voice choked with pain. “So I pushed him and pushed him some more, trying to make him normal. I was wrong. I pushed so hard he left yeshivah, left Yiddishkeit, and his blood is on my head.

“I call him every Erev Yom Kippur, asking if maybe he’s ready to come back. I ask him mechilah again and again. We simply didn’t know.”

The Relief caseworkers quickly learned how to address clients from within different neighborhoods and demographics, but when it came to out-of-town communities, they were at a loss.

Mrs. Nancy Friedberg of Toronto had the idea of opening a local branch.

“So after New York and Lakewood, we started in Toronto, then Eretz Yisrael, Baltimore, upstate New York, London, and California. Now we’re opening in Montreal, b’ezras Hashem.”

Relief: The biggest international organization you never hear about, everyone’s little secret.

Power, Influence

I finally catch Dr. Shmuel Mandelman, a neuropsychologist at New York City’s Weill Cornell Medical College, late on a rainy summer night. The Ivy League-educated-and-trained doctor with the half-yearlong waiting list chooses his words carefully. “The evolution of the frum public’s awareness and acceptance in regard to mental health is a tremendous blessing, and that blessing is, to a great extent, a result of Relief.

“The community does not realize that they would never have access to the level of clinical care that they have without Relief. Relief has forged relationships with some of the most renowned and inaccessible clinicians. Given the level of respect those clinicians have for Relief, they can connect patients to those clinicians.”

He speaks of the level of dedication. He says, “When it’s about one in the morning and the world is asleep, that’s my time to connect with Duvi Kessner and we are able to update each other on the cases we work on together. I had a call with one of the referral specialists on Tishah B’Av. It’s personal, so it never really ends.”

I share the comments of a particular clinician, who mentioned to me that he feels like Relief are the kingmakers, with the power to make or break an aspiring clinician.

Dr. Mandelman doesn’t dispute the premise, but he puts it into perspective. “Relief is acutely aware of the power and influence they have and are extremely responsible about it. There is no arrogance; they have a remarkable understanding of what they are and what they are not. Every single caseworker there knows his own strengths and weaknesses, and they never play clinician — rather, they are singularly focused on what’s good for the patient. They have high standards and have set the bar in terms of the quality of mental health care.”

“I find it impressive,” says Dr. Ronen Hizami, a psychiatrist with several New York-area offices, “that the Relief referral specialists are not scared to ask questions. On several occasions, they’ve called to run a case by me and ask whether it made sense. They asked me what they should be asking. These are cases that I am not involved in, and that practice has earned my respect.”

Dr. Hizami added that Relief never dictates treatment. “Unfortunately, some very well-meaning community-based askanim feel they can dictate treatment. I have heard nightmare stories about the askanim taking patients to the doctor, being in the room and dictating the treatment. I have never experienced this with Relief.”

Patients in treatment often face the challenge of having to change providers for a variety of reasons. Relief patients aren’t left to navigate this on their own, because the caseworker knows the patient history and has been there every step of the process, so if there’s a shift in personnel, the patient can be referred elsewhere.

“That continuity of care is invaluable,” says Dr. Mandelman.

W

hen Rabbi Ornstein marks the frum community with an A+ in terms of its approach to mental health, he adds a comment to that same theoretical report card.

“We’re finding that the first responders, in terms of mental health, aren’t just parents and educators. The shul rabbanim play a critical role, because so often, a congregant isn’t sure if there really is something wrong with a family member or not. There’s every reason to say, ‘Nah, nothing’s wrong,’ but just in case, he’ll mention it to the rav — because he doesn’t want to share it with his parents or friends. The rabbanim have proven to be our biggest ambassadors, reassuring people that it’s okay, that there’s help, that treatment works.”

Along with seminars for rabbanim, Relief sponsors seminars for mechanchim, chassan and kallah teachers, clinicians, OB-GYNs, nurses, and so many others.

“We just want people to live full, ehrliche, happy lives. We see it again and again — people don’t think they can be helped, but they can. They really can,” Rabbi Ornstein says.

A brief flash of pain clouds his features. “When Rav Chaim Epstein spoke for us, he said, ‘On the way here, I was thinking what mitzvah it is to speak about the importance of mental health. Maybe it’s chesed, maybe it’s bikur cholim. Then I thought, no, rabbosai, it’s something else. It’s pidyon shevuyim. Those who suffer from mental illness are in prison.

“ ‘And, rabbosai, if they don’t get help, it can be a lifelong sentence.’ ”

ifteen years in, it’s clear these two men have built something special.

On average, Relief receives over 10,000 calls per month, resulting in approximately 800 new cases. Including older files, Relief deals with close to 2,000 individual cases each month.

I wonder how it is that they haven’t been broken by the conveyor belt of Yiddishe tzaros that keeps coming, coming, coming, day in and day out.

“I was at a chasunah,” Sendy Ornstein says, “because I’m friendly with the father of the kallah. As I passed by the chassan, whom I didn’t know, he clutched my hand tightly, pulling me back. ‘You took my calls,’ he said, ‘a few years back.’

“I looked at him, vaguely remembered something.”

“ ‘There are 600 people here,’ he said, ‘but only you know how long the journey was, how hard it was for me to get here. Only you know,’ the chassan said, ‘what a happy chassan I really am.’

“That helps me go on. For sure it does.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 728)

Oops! We could not locate your form.