Season of Song and Fire

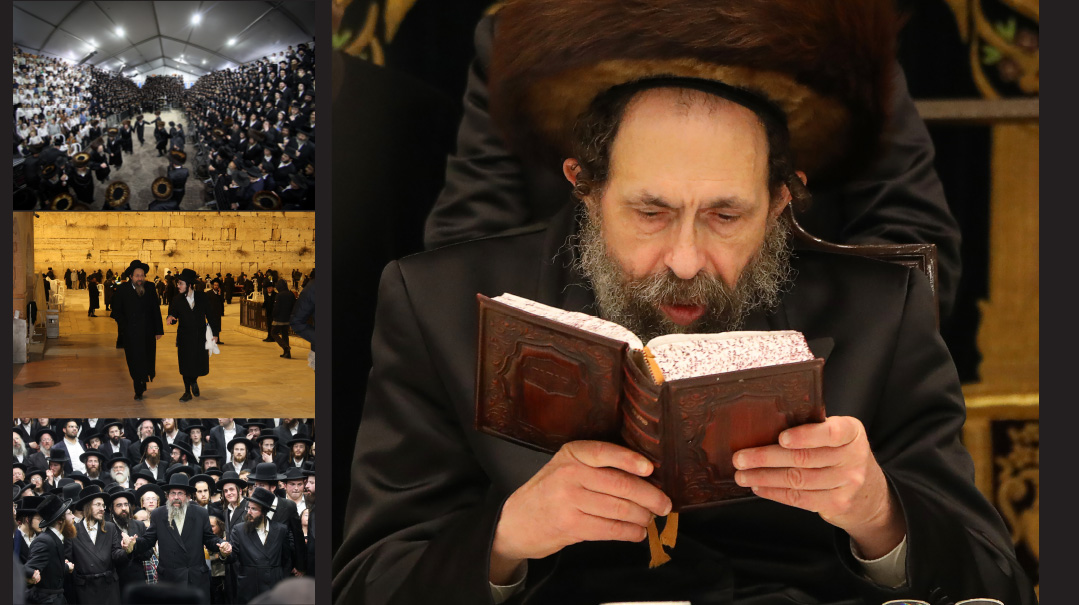

Rav Mottel Zilber’s inner fire ignites souls across the globe

Photos: Mishpacha, Toldos Yehuda-Stutchin archives

Rav Mordechai Zilber never intended to become a rebbe. But then he became a conduit for the Torah of his teacher, Rebbe Yehudah of Stutchin ztz”l, and today, Toldos Yehudah-Stutchin is its own fiery corner of Torah and avodah, with masses of talmidim flocking to Reb Mottel as he opens the gates to the deepest levels of service

It’s 1:30 a.m. on a warm Shabbos night in Jerusalem. Inside a massive tent erected for the summer, a huge crowd of Yidden stand shoulder to shoulder, their eyes fixed on a slight figure at the head of a long table. The haunting notes of a well-known niggun rise and fall, filling the air with longing. Suddenly, the Rebbe’s voice — pleading, insistent — takes over: “Oy, libi uvesari yeranenu l’Keil Chai — My heart and my flesh, my heart and my flesh, will sing out to the living God.” The crowd responds, two thousand voices echoing the ancient cry with the haunting tune.

The niggun eventually shifts into dance. The Rebbe joins the circle, his feet moving with such speed and intensity that the crowd struggles to keep pace. It’s as if the holiness of Shabbos itself animates his thin frame.

To step into this tent is to enter a separate universe. Chassidim in both spodiks and shtreimels together with clean-shaven Litvaks stand alongside knitted-kippah wearers, as external boundaries dissolve. The magnet is Rav Mordechai Menashe Zilber, known simply as “Reb Mottel,” the Rebbe of Toldos Yehudah-Stutchin.

A man who began life in Paris, grew up in Boro Park, and now splits his time between Brooklyn and Jerusalem, Reb Mottel has become a spiritual phenomenon. His gatherings are part tish, part spiritual revolution, drawing those who yearn not only to belong but to search, to seek, and hopefully, also to find.

“It’s not just a tish,” says one avreich who spends every Shabbos with Reb Mottel during the weeks he’s in Eretz Yisrael. “It’s a meeting with eternity. You leave a changed person.”

For over three decades, Jerusalem has hosted this special summer pilgrimage. Each year, during the months of July and August, the Rebbe of Toldos Yehudah-Stutchin leaves his base in Boro Park and takes up residence in the Holy City, where throngs pour into his gatherings — his Shabbos tishen and weekday shiurim — to hear his words of Torah and chassidus, and to witness the fiery passion of his avodah.

The annual custom started years ago when, after spending several summers in the Catskills, Reb Mottel decided instead to travel to Eretz Yisrael. During those first few summers, staying in his father’s apartment in Har Nof, he basically kept to himself — no public shiurim — preferring to spend quiet days immersed in Torah learning. But he did venture out to daven in the nearby Vitzhnitz beis medrash, and that’s how he eventually became close to the Yeshuos Moshe of Vizhnitz (the previous Rebbe), who gave him great honor and drew him close.

The choice to spend his summers in Eretz Yisrael — practical at first — soon morphed into a spiritual tradition. For over 35 summers, the Rebbe has made Jerusalem his base, and each year the gatherings only grow larger.

Reb Mottel continues the legacy of the Ropschitz dynasty and Rav Naftali of Ropschitz, a towering disciple of Rebbe Elimelech of Lizhensk and Rebbe Menachem Mendel of Rimanov, known for his profound wisdom, sharp sense of humor, and profound musical gifts. Two hundred years later, Toldos Yehudah-Stutchin carries that flame forward, as the melodies, the emotional intensity, and the hunger for Geulah that marked Ropschitz are alive in Jerusalem’s summer nights — and all year long in a beis medrash in Brooklyn. For the chassidim, it’s a living tradition stretching back two centuries.

As the Jerusalem gatherings swelled year after year, the need for space became critical. The smaller halls that were rented couldn’t contain the growing crowds. Chassidim were thrilled when last summer, a huge tent with seating for 2,000 was erected in the courtyard of the main Bais Yaakov seminary on the corner of Minchas Yitzchak and Yirmiyahu streets.

You might think that, with such a crowd of admirers and supporters, Reb Mottel would be spending these months in one of the new beautifully furnished luxury high-rise apartments that have dotted the city in recent years. But in fact, we meet in a modest apartment, Rav Mottel sitting at a folding table surrounded by a stack of seforim and a disposable coffee cup, bent over Shaar HaKavanos of the Arizal.

Without getting into the contentious issues of drafting yeshivah students or the quagmire of Israeli politics, Reb Mottel doesn’t dismiss the miracle of Jewish survival in Eretz Yisrael. “There is no natural explanation,” he says. “Life here is a continuum of miracles, infused with an abundance of Torah and chassidus not found since the times of the Tannaim. HaKadosh Baruch Hu guards those who dwell in the Eretz Yisrael in a way that defies the natural order — that is His promise, and anyone who lives here and opens his eyes sees it. If not for my kehillah in the US, I would stay here all year round — it’s the greatest zechus.”

New Gates

Born in Paris in 1951, Mordechai Menashe Zilber was a postwar child of survivors. His father, Rabbi Simcha Alter Zilber, and his maternal grandfather, Rabbi Nota Scharf, were devoted followers of the Stutchiner Rebbe, Rav Yehudah Horowitz “Reb Yehudale”, known for the name of his famed sefer, the Minchas Yehudah. Both families had their roots in the Polish chassidic communities shattered by the Holocaust, and in the aftermath clung with renewed strength to their spiritual heritage.

When Reb Mottel was two years old, the family emigrated to the US and settled in Boro Park, where they joined a growing community of survivors who rebuilt their worlds around their rebbes. Reb Yehudale, the Stutchiner Rebbe, also settled in Brooklyn, drawing around him a small but fervent circle. It was in that atmosphere — of brokenness fused with fierce loyalty and tenacity — that Reb Mottel grew up.

His early education was in the Klausenburg and Satmar chadarim where he first encountered living tzaddikim. He often recalled the awe he felt when the Satmar Rebbe personally came to test the children on their Gemara learning.

“Children who see such figures,” Reb Mottel would later remark, “stay connected to something holy.”

As a teenager, he entered Torah Vodaath, where he became known for his unmatched diligence. Classmates remember him arriving at summer camp with a suitcase full of seforim, and then learning straight from morning until night.

At Torah Vodaath, he connected with some of the greatest roshei yeshivah of the postwar era: Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, Rav Avrohom Pam, Rav Gedalia Schorr, and Rav Eliyahu Chazan. He also formed a close bond with Rav Yisrael Belsky, with whom he learned Choshen Mishpat in depth. Rav Belsky once said of him, “He’s the only one who understands me… He’ll be the Rav Moshe Feinstein of the next generation.”

Another towering influence was the mashgiach Rav Moshe Wolfson, who would become his father-in-law. Rav Wolfson saw in the young man not only brilliance but a soul on fire for avodas Hashem. Their relationship, sealed by marriage, placed Reb Mottel at the heart of a spiritual dynasty that combined Lithuanian depth with chassidic warmth.

Alongside his roshei yeshivah, Reb Mottel remained deeply bound to the Stutchiner Rebbe, whom he referred to simply as “der Rov” and from whom he received guidance in chassidus and avodah. The Rebbe once said of him: “This is my portion from all my toil.” In another instance, when giving out shirayim, he told young Mottel, “You need to distribute shirayim.” Those words would later prove prophetic.

Stories of Reb Mottel’s diligence abound. As an avreich, friends recalled him sitting down to learn after Shacharis and remaining there until nightfall, barely moving. Motzaei Shabbos sessions with his brother sometimes stretched six hours. Alongside this discipline, he cultivated a probing mind and a thirst for depth. He absorbed the Maharal, the Ramchal, and Chabad seforim, and then, a chance encounter with Rav Hutner’s Pachad Yitzchak transformed his thinking. He later said those works opened “new gates” in his understanding.

When he was 28, a friend gifted him a set of Zohar. The Rebbe urged him to begin studying it, soon followed by the writings of the Arizal. Later, under the guidance of Rav Fishel Eisenbach — longtime rosh yeshivah of Shaar Hashamayim yeshivah in Jerusalem and one of Israel’s foremost mekubalim — he delved into the intricate system of the Rashash. The two initially met when Reb Fishel was visiting the US, Reb Mottel taking full advantage of the guest mekubal. Reb Fishel was quite astonished to meet such a treasure in America, and he asked Reb Mottel to come to Eretz Yisrael and to his yeshivah. And indeed, from then on, when Reb Mottel would come every summer, he would spend his days learning in the yeshivah of the kabbalists together with the Yerushalayim mystics. During those months, Reb Fishel was his private chavrusa, teaching him the foundations of the system of the Rashash. Reb Fishel would later say, “I gave him over all my wisdom.”

I’m Just the Teacher

Reb Mottel, an avreich of rare spiritual depth, never intended to become a rebbe. But when his teacher and mentor, the holy Rebbe Yehudale of Stutchin, passed away in Cheshvan of 1981, the chassidim were left bereft. They buried him in the ancient cemetery in Teveria, alongside the disciples of the Baal Shem Tov.

In those uncertain days, a group of young chassidim remained in Eretz Yisrael, lost and directionless. Seeking guidance, they turned to the Steipler, who first offered comfort: “The Master of the World does not abandon His servants.” Then he related a custom of chassidic succession: If a rebbe left no son, or no son worthy of leadership, the mantle falls to the most distinguished disciple. For the Stutchiner chassidim, there was no question who that was.

Support for Reb Mottel to take up the mantle of leadership came from various corners, including from Rebbe Yehudale of Dzikov, then in London, as well as the Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe.

At the time, a large group of Reb Mottel’s talmidim and followers formed their own beis medrash, which would come to be called Toldos Yehudah-Stutchin.

(Meanwhile, there is also a continuation of Stutchin itself, through the grandson of the Minchas Yehudah. While the Minchas Yehudah had no sons, he did have a daughter, Chana, who was married to Rav Ovadia Yudkowsky, a talmid of Rav Aharon Kotler. His son, Rav Leizer Yudkowsky, a talmid chacham who embraced his zeide’s chassidus, is today known as the Stutchiner Rebbe of Boro Park. Reb Leizer carries on the Ropschitz legacy in his own way. As a musician himself, singing and crying, and even forging important connections with disenfranchised youth, are part of what makes his beis medrash unique.)

In the past four-plus decades, Toldos Yehudah-Stutchin has grown into its own vibrant community, with hundreds of bochurim and avreichim studying under Reb Mottel’s dynamic and caring guidance. Because while others see him as a rebbe, he remains, above all, a teacher, a conduit and a living link to the great tzaddikim of the past.

Yet Reb Mottel’s approach to leadership is strikingly humble. He sees himself not as a ruler, but as one among many roles in the community — there’s the gabbai, the chazzan, the baal korei, and he sees his function as the one teaching Torah at the tish, where he sits in awe, as though the Minchas Yehudah is still presiding at the head. He also doesn’t wear the formal rebbe’s kapoteh, maintaining the reverence a chassid has for his teacher.

At the tish, Reb Mottel will first read from the sefer Minchas Yehudah before offering his own insights — always rich, layered divrei Torah in their own right. Afterward, he’ll share stories of tzaddikim and holy figures, drawing listeners into the spiritual worlds of previous generations. And then come the niggunim and dance, carrying the energy from a summer night in Jerusalem or a Shabbos in Boro Park to the far reaches of the chassidic world.

Reb Mottel’s path, however, wasn’t shaped alone. After the passing of the Minchas Yehudah, he sought guidance from Rebbe Yitzchak Kalish of Amshinov America, who encouraged him to continue learning kabbalah and plumb the secret, hidden layers of Torah. He was also close with the Rebbe of Tosh, traveling to him at least once a year.

These influences shaped Reb Mottel’s own ritual and spiritual practices. Every Shabbos during Shacharis, he dances in a fiery, meditative trance for close to half an hour at Keil Adon, a practice known among his followers as “Shevach,” inspired by his time in Tosh. Similar dances occur during Bo’i b’shalom in Kabbalas Shabbos. Those interludes are so intense that afterward, he often relies on other mispallelim to steady him.

At weddings or other celebrations of his chassidim, his devotion is all-consuming. Reb Mottel can dance for two hours straight, eyes closed, body practically weightless. These are no performances, though — they’re expressions of profound avodah, devotion in motion, connecting Heaven and Earth.

Beyond the Garb

But for all of his humility, Reb Mottel’s approach as a leader of a kehillah is both bold and disciplined. He doesn’t shy away from stating his views on pressing issues, challenging what he feels are distorted customs, and critiquing trends within the chassidic world. Yet he makes a clear distinction: While so many look to him for guidance, he doesn’t consider himself an authority on the leadership of the generation, and deliberately refrains from involvement in political matters or the general governance of the community.

What he does speak with authority about is yeshivah education, as so many bochurim across the yeshivah spectrum looking for additional depth and inspiration find their way to his shiurim. One thing he laments is the uniformity that pushes every student through the same track.

“I believe there is room to give much more choice to every bochur,” he says. “One is good in analysis, another in halachah, a third in bekius. A talmid discovers his place by seeing where he grows, where he thrives. Torah is vast — there should be options.”

There is another element as well. He feels the key to the success of the next generation, to offset the dropout phenomenon and pervasive spiritual malaise, is experiential.

“If a father has enthusiasm in Torah, joy in Shabbos, vitality in prayer, this refracts onto his children. If a person attaches himself to a true rebbe, inflamed by holiness who radiates devotion, who is in his entirety a true eved Hashem, it penetrates his own nefesh — that holy light gets transmitted, even in our coarse generation.”

And yet, if someone does fall? “Always draw them close. The light within will return them to the good,” he says with assurance.

In the heart of Reb Mottel’s teachings is the path of chassidus, but that, for him, means much more than a person simply remaining connected to his family’s particular group.

“By nature,” Reb Mottel explains, “a person belongs to a community, and that’s a very good thing. But in addition, for real growth, one should find a rebbe who speaks to his heart, who elevates and inspires, according to the root of his own soul. You don’t choose a rebbe just in order to make life easier.”

For over forty years, Reb Mottel has given thousands of shiurim across the breadth of chassidic literature — Mesillas Yesharim, Tanya, Maharal, Likutei Moharan, and more. His shiurim are renowned for their clarity and order, but for Reb Mottel, it doesn’t count unless it’s somehow transformative.

Yet discovering real depth and meaning in a generation faced with temptations at every turn is admittedly daunting.

“Of course, every generation has faced its own trials, and some have been particularly brutal. But today’s challenges are in a totally different realm,” Reb Mottel says. “And perhaps the main challenge today is the very difficulty of being able to endure trials. Temptations lurk all around, and people often fall. Yet each person has the strength to overcome, if only they recognize and tap into that strength.”

He rejects excuses about “decline of the generations.” Every soul, he quotes the famous gemara sourced in the very first sentence of Tanya, is commanded to be a tzaddik, even in 2025.

“This proves that Hashem believes in us — that there is someone to speak to,” he says.

It’s clear that his talmidim — no matter which kehillah they affiliate with — have gotten the message.

“After one of his shiurim,” says one bochur with a short jacket and bent-down hat, “you feel like a different person. You see the world with new eyes.”

Reb Mottel warns against superficial piety unaccompanied by Torah learning and sincere prayer, or customs that have lost their meaning and become a mere label of affiliation. “Today,” he notes, “many wear the flag of a particular chassidus, yet have no true connection to its path or to the essence of chassidus itself.”

He extends this to the ability to distinguish genuine reverence from partisan loyalty or empty propaganda. In his view, much of the friction between courts stems from this failure to separate core principles from secondary disputes.

“This is far from the way of the Baal Shem Tov, whose goal was to effect transformation,” he explains. “Whether through deep, analytical kabbalistic study or through mystical insights into the mitzvos and even daily living, that learning must ultimately influence the person’s actions and character.”

He encourages students to find their own path within these texts — from the writings of Maharal and Rav Tzaddok HaKohein to sifrei Chabad and Sfas Emes — each its own doorway to spiritual growth.

Reb Mottel, who never shies away from speaking honestly in his uncompromising pursuit of emes on both an individual and communal level, voices concern over what he sees as a troubling gap in the mainstream chassidic world between knowledge and rote custom. He says it’s time for people who identify as chassidim to own the Torah of chassidus.

“Many people across the spectrum of Jewish learning study these topics, either under the heading of chassidus, Jewish mysticism, or of ‘Machshevet Yisrael,’ but either way, they become knowledgeable in the concepts of pnimiyus HaTorah, whether or not they really live them,” says Reb Mottel. “Yet take a Yid who goes with the whole chassidic levush and speak to him, and it will often become clear that he’s an am ha’aretz in these matters.”

Wave to Hashem

A tish in Toldos Yehudah-Stutchin has a vibe all its own. On Friday night, the niggunim begin softly and end in roaring intensity, interspersed with teachings filled with gematrias and other hints and riddles. At Shalosh Seudos, the mood is Ropschitz. Reb Mottel sits in deep dveikus, barely moving as he sings Bnei Heichala and expounds on secrets of Torah with quiet simplicity.

And that’s just on a “regular” week.

If Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are the trembling heart of the Jewish calendar, then Succos — zman simchaseinu, the time of our greatest joy — is its crown. In Stutchin, the atmosphere is nothing short of electric.

During these days, davening stretches on for hours, as Reb Mottel moves through the crowd, his presence felt in every corner — and that’s when he’s not dancing. When he gets to the words “kulam ahuvim” during Shacharis, he breaks out in a whirl, a practice he inherited from previous rebbes.

But nothing compares to the naanu’im — the ritual waving of the arba minim. When he sings the niggunim connected to the naanu’im, it’s as if his whole being strains with longing.

Reb Mottel often laments that while people will spend exorbitant sums on a lulav and esrog, they never truly taste their sweetness. “It’s such a shame,” he shares. “Our ancestors knew the deep joy and revelations inherent in waving them before Hashem. Today, after spending a fortune on a ‘pefect’ esrog, how many really appreciate what to do with it once it’s in their hands?”

Late into the night, Reb Mottel leads the Simchas Beis Hashoeivah, as the hours slip by in a whirlwind of music and dance. And all of this joy builds toward Hoshana Rabbah, the climactic day of Succos. After Hallel, before beginning the hoshanos, Reb Mottel delivers what his chassidim call “a special Torah,” a teaching centered on redemption.

“He says things that are truly awesome,” one talmid relates. “A trembling seizes the room, and the entire crowd breaks into tears.” For those who are familiar with chassidic writings, it’s no surprise: All the holiness of Tishrei funnels into Simchas Torah. “It’s the peak of all peaks. The atmosphere is entirely different.”

On that day, Reb Mottel is often withdrawn, absorbed in lofty thoughts. He barely eats. At the tish, following the tradition of his teachers, he reviews each stage of avodah that the Jewish people passed through during the Yamim Noraim, the High Holidays, weaving verses together with sobs and fiery words.

“I can’t explain it,” the talmid continues. “But if you’ve never seen it, you’ve never seen joy and awe so intertwined.”

R

eb Mottel speaks of our generation’s struggles and challenges, yet he believes in the power of every Yid to tap into the pure places of his soul and soar. And always, he returns to a single refrain: There is one cure for every struggle, one all-encompassing remedy for every soul.

“Ta’amu u’re’u ki tov Hashem — Taste and see that Hashem is good. Whoever merits to taste even a drop of true avodas Hashem will find the answers,” he says.

It seems like a pretty simple recipe. Because in the presence of Rav Mordechai Menashe Zilber, somehow the ordinary becomes extraordinary. To sit with him is to glimpse the fire of faith itself — a reminder that, even in a coarse, dark world, holiness can burn brightly.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1081)

Oops! We could not locate your form.