School’s Out

| January 20, 2026What triggered the state's takeover of the Lakewood school district?

Lakewood’s public-school Board of Education has lurched from one crisis to another — and now it’s been taken under state control. What does Trenton’s move mean for Lakewood schooling

Like a speaker with only one good vort, there’s an unfortunate subculture of haters who seek to twist every story to somehow be about the Jews. When “Minnesota” became a code word for “Somali immigrants ripping off honest taxpaying Americans,” these people immediately began working on a new dog whistle meaning for “Lakewood” or “Kiryas Joel.”

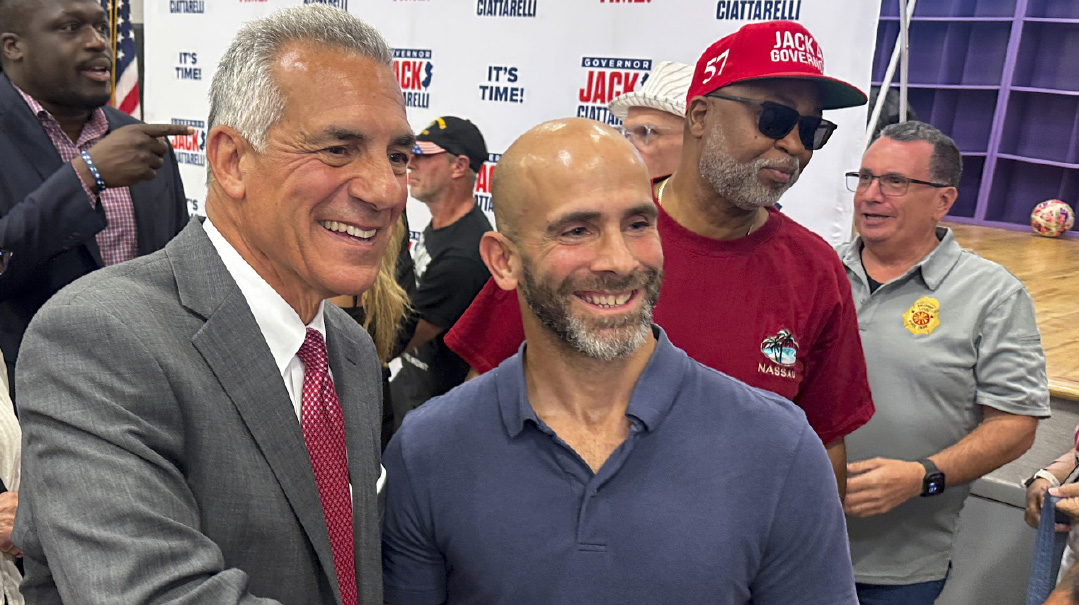

When NJ Governor Murphy took over control of the Lakewood Board of Education, just six days before his term was over, they gleefully identified their chance. “Murphy Administration Files Attempt to Take Over Lakewood BOE,” the headlines announced. The sound of it smacked of a dad wading in to a scuffle, or a mom cleaning up her kids’ mess. New Jersey pundits up and down the state cried “Minnesota!” and hurried to tick off the similarities they could find between Lakewood’s Jews and Somalis in Minneapolis (spoiler: none, really).

But what does the state’s unorthodox decision to parachute into an Orthodox town and commandeer the reins of the public school district really mean? What triggered it, what will happen going forward, and how will it impact those Jews in Lakewood?

“At this point, it’s impossible to tell,” Assemblyman Avi Schnall tells Mishpacha. “This takeover is unprecedented. We don’t know what the state plans to do or how. It could be a really positive step, or negative.”

Unique Demographic

New Jersey has taken over school districts in the past. It still controls the one in Camden, and only returned Jersey City, Paterson, and Newark to local control after nearly thirty years of state rule. “But those were all big-city districts,” explains Agudath Israel’s New Jersey director Shlomo Schorr. “This is the first time the state is trying to take over a suburban board of education. It’s uncharted territory.”

The distinction makes all the difference in the world. The previous four takeovers were triggered by mismanagement on the part of local officials, Rabbi Schnall explains. “But the state knows full well that Lakewood Board of Education suffers from a revenue problem (lack of funding), not a management problem (irresponsible spending).”

Admittedly, the optics of the BOE’s books are disastrously bad. The district has been running in the red for years, with an annual shortfall of close to $40 million. They’ve been borrowing money from the state Department of Education to close the gap, and the mounting debt stands close to $200 million, with no hope of ever being paid back.

But the imbalance is caused by Lakewood’s mandated expenses — funding transportation, special education, and more for 50,000 children, while receiving state aid for only 4,500. “The state is well aware of the bind Lakewood is in,” Schnall explains. “Over the past decade, more than a dozen state-appointed fiscal monitors and auditors have reviewed Lakewood’s finances in depth, looking for ways to cut expenses and save money. Without exception, every one of those monitors reached the same conclusion: Lakewood isn’t spending more than it has to — it’s just not receiving enough funding.”

“Even now, we currently have four state monitors watching our books,” BOE member Shlomie Stern tells Mishpacha. “We have a fiscal monitor, governance monitor, special education monitor, and busing monitor. It’s not clear what more a state takeover can add.”

“This takeover is not about uncovered fraud,” Schorr says, “contrary to many implications on social media and in print articles that there’s a whole Minnesota Somali situation here. That’s absolutely not the case.”

That didn’t stop former gubernatorial candidate Bill Spadea from leveling such accusations on his daily radio show, alleging widespread fraud in the district, and suggesting the takeover means New Jersey taxpayers will now be stuck with the bill. Spadea jeeringly offered to “buy the first roll of string for $5.99 to put an eiruv in the school buses, so that boys and girls can ride the same bus,” claiming that while he respects religious freedom, “there’s always a workaround.”

YouTuber Tyler Oliviera jumped on the bandwagon as well. After publishing a vlog about KJ titled, “Inside the New York Town Invaded by Welfare-Addicted Jews,” he expressed his intention to go after Lakewood and its school board woes.

Numbers Don’t Care

Over a decade of state monitoring has made clear to New Jersey Department of Education Commissioner Kevin Dehmer is that Lakewood’s grossly unbalanced spreadsheet is not a result of scams or fiscal irresponsibility, but the unique nature of Lakewood’s demographics. New Jersey provides over 50% of operating funding for 600 school districts, totaling over $12 billion per year. The amount of state aid given to each district is determined by a complex calculation allocated by the opaque 2008 School Funding Reform Act (SFRA), a formula that looks primarily at the number of students enrolled in public schools in the district. That works for most towns, which average about only 14% of children in private schools.

Enter Lakewood, the district in which 50,000 children — over 90% — are enrolled in private schools, but the BOE only receives funding based on its 4,500 public school enrollees. Although it doesn’t have to educate the private school children, it is still mandated by state and federal law to pay transportation for nearly 30,000 students living some distance from their school. Transportation for all students costs the board over $48 million per year.

The FAPE (Free Appropriate Public Education) Act mandates that the town must provide special-education facilities for qualifying students. As Lakewood public schools don’t have adequate special-education facilities, the BOE is forced to spend millions to send students to out-of-district special schools like the School for Children with Hidden Intelligence (SCHI).

State aid, which accounts for only ten percent of the town’s students, simply can’t support these mandated expenditures.

Ambiguous Takeover

The state’s filing seems to dispute the facts somewhat. Despite the testimony of its own monitors and oversight, the 638-page document repeatedly accuses the Lakewood BOE of mismanagement and neglect. It points to the bloated budget shortfall, poor student outcomes and a “culture of low expectations.” Among the points it makes:

- State reviews found “issues” with the district’s governance, curriculum, transportation, and finances.

- Graduation rates among public school students are 10% lower than state average.

- Standardized test scores are 10-30 points lower than state average.

- Structural deficits amount to more than $100 million per year.

- The BOE doesn’t discuss agenda, policy, or use committee reports to determine actions.

- Although 77.2% of public-school students speak Spanish as a first language, only about 15% of documents online are translated into Spanish.

- Students cope with poverty, late jobs, poor English proficiency, and living conditions.

The state’s argument draws heavily on a ruling in Alcantara v. Allen-McMillan, a 12-year legal battle waged by Aron Lang, a Lakewood math teacher, lawyer, and BMG talmid, along with Professor Paul Trachtenberg, former Rutgers law professor and an expert on public education. The document references the decision nearly forty times.

Investing seemingly endless personal expense and time, in 2014 Lang and Trachtenberg sued the state education commissioner on behalf of Lakewood public school parents, aiming to force the court system to fix the school funding formula and provide adequate aid to Lakewood. The litigation was crafted on a two-step plan:

Prove that the Lakewood School District is failing to fulfill its obligation under the state constitution to provide a “thorough and efficient (T&E)” education to its students

Prove that the failure is rooted in the inadequate funding provided by SFRA, thereby showing the SFRA law to be unconstitutional in the case of Lakewood, striking it down and triggering more funding

The Lakewood BOE battled Lang and Trachtenberg throughout the prolonged litigation, which continued even after Lang moved out of Lakewood.

In 2021, an administrative law judge established the validity of the first premise in the case — that Lakewood was failing to educate its public school students. The commissioner of education fought the finding, but an appellate court confirmed it in 2023. However, the courts did not agree with the second assertion, blaming the district for mismanagement instead of finding the funding formula faulty. The filing for takeover quotes extensively from the decision in the case.

Meanwhile, the pair have petitioned the state supreme court to consider the second step in their claim, but little has moved in over a year.

Lang and Trachtenberg told Mishpacha that they remain convinced of the rectitude of their efforts. “The linchpin of the State’s takeover effort is the finding in our case that Lakewood students are being denied T&E,” Trachtenberg admitted, but stressed that “the state continues to refuse to acknowledge that SFRA does not work adequately for Lakewood….”

The State’s explanation for the deficiencies? Local mismanagement and failure of Lakewood taxpayers to raise enough money for the schools.

“At every opportunity throughout the eleven-plus year case we have ridiculed the State’s argument that the denial of T&E was a result of local mismanagement,” he added. “We coupled that with arguments that the State had multiple state monitors, with broad statutory powers and duties, assigned continuously to Lakewood for 11 years. Two of the best and most senior of them testified under oath before the ALJ [administrative law judge] in 2019 that Lakewood had a revenue problem, not a spending problem.”

Both Lang and Trachtenberg suggested the state takeover may be a delay tactic to prevent the supreme court from invalidating SFRA.

Feeling the Heat

What effect could the state takeover have on nonpublic-school parents in Lakewood? Four areas of concern are being widely considered: steep tax hikes, disruptions to transportation, decrease in remedial education funding, and changes to the way the district serves students with specialized needs.

According to Schorr and Stern though, most of these worries are unfounded. In fact, they float the optimistic hope that the takeover may very well be the solution the district has been seeking.

What does the state intend to do with Lakewood School District, if its takeover is approved? It’s published a plan with the following stipulations:

- New Boss: The state will replace Superintendent Laura Winters with a new state district superintendent, who will have full supervisory authority over the district for an initial term of up to three years. Commenting on the decision, Lakewood BOE member Shlomie Stern noted that “Winters has been doing an amazing job… we have a superintendent that actually cares about every single kid in the entire district, private or public.”

- Bring in the Pros: Five “highly skilled professionals” will be appointed to provide direct oversight in the critical areas of governance and legal compliance, special education, transportation and operations, fiscal management, and nonpublic student services.

- School Board Takes a Seat: The currently elected Lakewood Board of Education will be stripped of its powers and will continue to serve only in an advisory capacity. The Education Commissioner will also appoint up to three new, non-voting members to the board.

- Homework: The district will be ordered to develop a comprehensive improvement plan within six months to address the identified deficiencies.

The plan says nothing about the hundred-million dollar question: Who will cover the district’s budget? Will the state forgive the $200 million it is owed? How is the grossly unbalanced expense sheet going to be fixed?

“My first instinct was to fight this takeover before the state Board of Education and the courts,” Stern says. “But if the state will now fund the district, or even if it just forgives our outstanding loans, that would be a significant benefit.”

Schorr thinks it’s highly unlikely that the state will start coughing up more money for Lakewood. “They’re likely going to take over the management and try to do it better,” he surmises. “The state and commissioner are well aware of the issues. Every budget for the last several years had to be approved by state monitors. They think there are some things they can still cut, and perhaps more revenue they can raise to close the gap.”

Here are some ways state control may impact locals.

- Tax increase. This is the most likely scenario. Although property tax increases in New Jersey are capped at 2% per year since the Christie Administration, the state has a mechanism to override it, and indeed has done so in Toms River and Jackson. It can impose a steep tax hike — like 20% or more — to cover the growing funding shortfall. Lakewood has a tax base north of $11 billion, among the largest in the state, but has a 1.032% school property tax rate, less than nearly 80% of districts. The state average was 1.376% in 2024.

- Auxiliary Services (Tender Touch, Catapult, et al). This money is safe, Schorr stresses. It is not part of the district budget, provided instead directly to students through Title 192 and Title 193 allocations. It does not figure in the budget at all.

- Transportation. It’s unlikely that state control can make any painful changes to transportation services. The school board is obligated by state and federal law to fund it for “mandated” students living far from school. Contrary to Bill Spadea’s “eiruv on buses” theory, most buses are full, particularly since the passing of a state law sponsored by Assemblyman Lou Greenwald and Lakewood’s Bob Singer, with tireless advocacy from Avi Schnall, that allowed buses to pick up children from multiple districts.

- Despite claims in the state’s Order to Show Cause to the contrary, Lakewood does not currently pay for courtesy (non-mandated) busing at all, instead arranging it for parents through a busing consortium called the LSTA. The organization actually saved the district $11.4 million per year because as a private entity, it is not subject to expensive contracting rules like government bodies are. Were the state to take busing away from the LSTA, it is likely to face higher costs, not lower. The state would also lose millions in school funding provided by Lakewood Township.

- The state filing complains that the “savings were not passed on to the district,” but Schorr points out that the claim is nonsensical — the $11.4 million is money unspent, not extra cash lying around that can be passed anywhere.

- Special Education. Lakewood spends high sums to send kids to SCHI and other out-of-district schools, because it does not have its own adequate facility. The state could theoretically try to set up its own special-education schools, keeping its 1,072 children with specialized needs in-district and saving money. But Stern doubts such a plan could come to fruition.

“We’ve explored this in the past,” he told Mishpacha, “looking at options like using the closed Ella G. Clarke school building. But the state monitors have said it’s simply too expensive to set up a facility to be worth it.” He notes that state rules could make it harder to qualify for services, in order to save money for the district.

The common theme we heard from askanim and elected officials is that it’s still too early to tell how the takeover, if it is approved, may play out. Instead of fighting it in court, Stern said the local board may ultimately decide to welcome the effort, depending on the details. “Ultimately, it’s not about who’s in charge, but about every single child getting what they deserve. And that remains our permanent goal.”

Confirmation Bias

When YouTuber Tyler Oliviera spent 40 minutes of airtime walking around Kiryas Joel with a mini-mic, he appeared to be looking for Nick Shirley’s gold mine.

Shirley struck gold allegedly exposing fraud and welfare abuse in a closed Minnesota Somali community, with spaces outsiders are not allowed to enter. He became a household name overnight.

Hoping to do the same, Oliviera roamed the streets of KJ accosting random people and digging for information. When he asked people whether or not they worked, most said they did, and provided details. Some said their wives did, and a few said they studied Torah. Nevertheless, Oliviera’s inexplicable conclusion was: “What I’m hearing is that they’ll gladly take money out of the American tax base to support their lifestyle.”

He also stomped around shuls, asking, “I’m not allowed in here because I’m a goyim, right?” but could not get himself kicked out.

Perhaps most fascinating about the accusations of leeching and dragging on society is the irony of whence they come.

Oliviera is a YouTuber. He fulfills no need in society, serves no purpose, assuages no lack. No one was missing his entertainment before he launched it.

Although he may style himself as an independent investigative journalist, it’s interesting to investigate that claim a bit. He launched his channel filming useful things such as trying to soak up a pool by wasting a million paper towels, running on a treadmill for 24 hours, literally spending all day going nowhere, and trying to bench-press underwater.

He then transitioned to “investigative journalism,” where his work would be better captioned as “inventive invasiveness.” Purportedly covering drug decriminalization, he recorded a man suffering from a drug overdose without his consent, and misquoted and exploited a politician. His videos are riddled with admitted false representation, secret invasive recording, attempting to pass off AI images as real, altering images, mislabeling locations and events to create false impressions, misleading editing, bias and racism, and exploiting poor or suffering people.

A colleague awarded Oliviera the title, “YouTube’s biggest liar.”

But wait, he has done something constructive! Oliviera published a video of himself joining a festival in an Indian village in which people jump into a pit of cow dung and then throw it at each other.

Contributing to a functional society? I’ll stick with KJ, thanks.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1096)

Oops! We could not locate your form.