Sacred Stamp

Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock left an enduring imprint on America’s yeshivah world

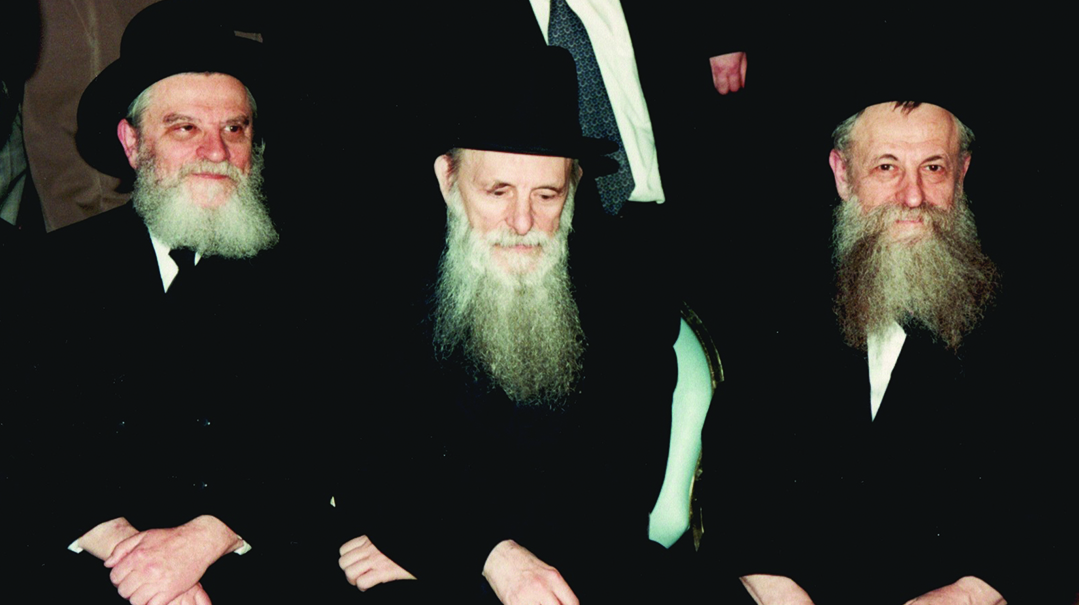

Photos: AEGedolimphotos.com, Family archives via COLlive

There are those who use the eloquence of words to reach others, each phrase and expression hitting with the force of a hammer’s blow.

Others use silence, a quiet, burning intensity creating its own sort of impact.

And there is a third sort, the rare individual who uses both — not silent, but also not a speaker. Words are chosen carefully, taken seriously — tools, perhaps, but not the goal. It’s not the oratory or rhetoric that inspires the listener, but the person himself.

That’s how Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock, who passed away last week at age 95, reached generations of students — stamping them with the unique imprint of a Long Beach talmid.

Back in time to Vienna of the 1930s. Reb Avrohom Feigelstock was a respected figure — a learned businessman who gave regular shiurim and was devoted to the Torah of his sons for whom he hired private melamdim. His wife, Gittel, was a great-granddaughter of the Chasam Sofer, the leading light of Austrian Jewry.

As the Nazi threat increased and it became clear that they would have to escape, the family split up: Yosef Yitzchok, not long after his bar mitzvah, ended up in Uruguay.

The next generation of roshei yeshivah was being cultivated in the yeshivos of Eretz Yisrael or in America, hearing chaburos and arguing in learning, but this bochur was in South America with no rebbi, chavrusa, or friend, utterly alone.

Not just alone, but lonely.

At a different time, Rav Yitzchok would occasionally do something out of character and speak about himself. It was a rarity, but at the Shabbos sheva brachos of his daughter to the son of his dear friend Rav Elya Svei, he allowed himself a brief moment of public introspection.

He reflected on his personal journey and Hakadosh Baruch Hu’s boundless chesed. The talmidim, unused to hearing their rebbi speak about himself, were spellbound. But then Rav Yitzchok did something even more unusual.

“I don’t know if I have any zechusim, but if I have a single zechus, a source of merit that allowed me to experience so many chassadim, it might have been this.”

Rav Yitzchok spoke about those years in Uruguay and said that while he wasn’t the only Jewish teenager there, he was the only one who didn’t join in any of the youth groups. These mixed-gender groups gave the young people a social dynamic, company, acceptance, something to belong to. But the Viennese bochur had a sense that he didn’t belong there, and so he stayed away.

“Perhaps,” he said, “this was the zechus that stood by me.”

He eventually came to America, joining his two brothers. Moshe was already in Beis Medrash Elyon and Hershel was in Lubavitch. (Rav Moshe Feigelstock, who passed away in 2015, would become rosh yeshivah of Yeshiva Tiferes Elimelech, and Rav Hershel, who passed away in 2020, would become principal of Yeshiva Tomchei Temimim Lubavitch in Montreal, Canada.) Moshe felt that his brother would do well in Torah Vodaath, and though Yitzchok had learned with his father until his bar mitzvah, he didn’t come into the yeshivah as a prodigy.

He had spent years on the run, and hadn’t attended a formal cheder since he’d been a young boy.

But Rav Gedalia Schorr saw something in the young man, and he encouraged him.

They learned together, they walked together, they often spoke — and in time, Rav Schorr paid his talmid the ultimate compliment.

He suggested that Yitzchok Feigelstock go learn under his own rebbi, Rav Aharon Kotler.

“It was a neis that the Rosh Yeshivah accepted me — I wasn’t on the level,” Rav Yitzchok would later say.

Perhaps it was a miracle. Part of that greater miracle called the rebirth of Torah in America and the miracle of the children born on these shores who would themselves take part in that rebirth, so many of them talmidim of this one-time immigrant.

He Kept Us Focused

Even in the world of Rav Aharon’s Lakewood, Rav Yitzchok stood out.

Rav Meir Hershkowitz, rosh yeshivah of Beis Binyamin in Stamford, would explain that the level of “kisharon” (talent in learning) in Rav Aharon’s shiur was very high. The intensity was high. The burning sense of achrayus was high. There was much to get lost in. “But Rav Yitzchok was the one who sat us down and reminded us that the ikar, the main thing, was to simply sit and learn, to know Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafos, to gain clarity in Torah. He kept us focused.”

Rav Aharon was quite taken by this talmid, and it wasn’t just about trust. Rav Aharon considered his talmid a baal eitzah, discussing matters with the bochur he referred to as his “peleh yo’eitz.” When Rav Aharon received a letter from the Brisker Rav, he learned it up together with Rav Yitzchok, trusting and teaching his talmid at once. A new door was opening before Rav Yitzchok — it was called mesorah, and he would master it as well.

Rav Aharon was traveling to Eretz Yisrael and a respected businessman, Mr. Julius Klugmann, was helping the Rosh Yeshivah with a particular klal issue. “If the Rosh Yeshivah still isn’t back, and I have questions, who should decide?” he asked. Rav Aharon thought for a moment, and said, “Feigelstock.”

There was a point at which Rav Yitzchok was considering leaving Lakewood. The Mashgiach, Rav Nosson Wachtfogel, called him over after Shacharis and made it clear that he wasn’t going anywhere. Rav Yitzchok was surprised, and asked why the mashgiach was so adamant. “Last night,” Rav Nosson said, “your zeide, the Chasam Sofer, came to me in a dream and said that I cannot let you leave Beth Medrash Govoha, because your place is here.”

Rav Yitzchok would marry into a home with a rich mesorah of its own. Mrs. Miriam Devora Fishbain had been left a young almanah, just 40 years old, charged with raising a house full of children and also running the business her husband had worked so hard to build.

But she was determined, and somehow, her daughters were sent all the way to New York to learn under Rebbetzin Kaplan, and she sent her pre-bar mitzvah son to learn in Torah Vodaath — she dared to dream of grandchildren who would illuminate the world. On a visit to Chicago, Rav Elchonon Wasserman stayed in her home and was impressed by her determination. Along with offering his brachos, he predicted that Torah would thrive in America because of families like hers.

The Fishbain children would stand tall, building homes of harbatzas Torah, chassidus, and chesed, each one leaving their mark — the daughters marrying Rav Avrom Barnetsky, Rav Chaim Gringras, Rav Yankel Finkelstein, Rav Mordechai Yehuda Lubart, Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock, and Rav Shimon Groner; the only son eventually gaining renown as the beloved rav of White Lake, Rav Shmuel Yosef Fishbain.

Rebbetzin Yocheved would take her place at Rav Yitzchok’s side — there until his last moments, dedicated to the mission as he was.

What’s with the Sugya?

After the passing of Rav Aharon in 1962, talmidim began to approach Rav Yitzchok to discuss topics in learning or life, confident that the Rosh Yeshivah’s vision for Torah in America had a faithful guardian.

Rav Yitzchok wasn’t dynamic and he wasn’t flamboyant, recall talmidim of that era. He was refined and tranquil, measured in speech and comportment, consistent and true.

He was a ben Torah.

After more than two decades in Lakewood — from 1948–1970 — Rav Feigelstock moved to St. Louis where he served as the rosh yeshivah, and soon after, he was asked to join the leadership of the existing yeshivah in Long Beach, New York.

Under his leadership, the Mesivta of Long Beach would achieve distinction. It would be marked by the caliber of its talmidim — all of them, regardless of level of learning and path in life, stamped as “mechunachim.” His mechunachim.

From his beis medrash would come forth rabbanim and roshei yeshivah, businesspeople and professionals, and legions of proud kollel yungeleit — all of them recognizable by their diligence, their determination to grow, their sense of communal responsibility, and the sense that they had been fashioned by a master educator.

He was molding the American ben Torah, and he was doing it his way.

It started with the shiur.

It wasn’t Rav Aharon’s shiur, but his own unique product, crafted based on what he thought the bochurim needed to hear. He didn’t thrill and he didn’t split hairs, but as alumni started to go forth into the world and make their mark, it was clear that his shiur was achieving the desired result.

The yeshivah learned through the cycle of yeshivishe mesechtos, and Rav Yitzchok’s shiurim were often the same, or similar, from cycle to cycle. And yet, he invested himself into each sugya as if it were the very first time he was saying shiur. One zeman, a talmid had thought there would be shiur on the very first day of the zeman, and was surprised that there wasn’t. He asked the Rosh Yeshivah about it.

Rav Yitzchok looked at him in shock.

“Voss heist, du meints as mir ken zuggen shiur bim-bim — Do you think we just say shiur spontaneously, without proper preparation?”

The shmuessen were not much different. He often referred to the same themes and ideas as the year before, but he spent all Shabbos afternoon preparing it, learning through the concepts yet again. They were being delivered for his talmidim, based on what they needed to hear.

It was an event. The Rosh Yeshivah would come into Shalosh Seudos and the room was suddenly quiet, the awe engendered not by any outside force, but from the essential chashivus of their rebbi.

The Rosh Yeshivah would sit in his seat, eating his challah and gefilte fish without ever bending toward the food, a picture of discipline and dignity. There would be zemiros, and the schmooze would begin.

Clear, solid, authentic, and true. He was a pikeach, a wise man, but he taught them that one doesn’t have to be naturally wise to be mefake’ach, to consider their every action and its consequences.

The Rosh Yeshivah was a fifth-generation descendant of the Chasam Sofer, yet he rarely quoted the Zeide, because the substance of the schmooze wasn’t for himself, but for them. He was rumored to be fluent in the entirety of Sfas Emes, but this sefer too often went unquoted, because the shmuess wasn’t about selling himself, but rather, reaching his recipients wherever they were holding.

Late on Motzaei Shabbos, after seder, the bochurim would gather in small groups and review the shmuess, looking up the sources and writing it over.

They were being given a way of life and they realized it.

There were themes, of course. The ikar, as he always reminded them, was to sit and learn.

A talmid was leaving the yeshivah for the last time. The son of a successful businessman, he expressed his thanks to the Rosh Yeshivah and his hope that he would one day be able to repay the yeshivah.

Rav Yitzchok didn’t hesitate. “The only way you repay the yeshivah is nuch a yohr in lernen, learning longer, learning more, becoming a talmid chacham.”

A talmid was once involved in a complex issue — three different parts, and each one thorny and involved — and he called the Rosh Yeshivah to seek guidance.

And just as he did in shiur, the Rosh Yeshivah proceeded to strip away the extraneous details, honing in on the real issue, helping the questioner himself see the situation clearly. It took time and it took concentration and it took laser-sharp acuity, and then, when the exhausting question was finally resolved, the Rrosh Yeshivah continued the conversation.

“And what’s with the learning?” he asked, as if reminding his talmid that this was the only goal, with all the issues that arise, and it’s crucial that he stay focused. What’s with the sugya?

It’s Your Nation

As part of the mission of creating bnei Torah who would one day themselves create bnei Torah, he invested the older bochurim with prestige and the responsibility that goes with it. One summer, two high-school bochurim were planning to visit Eretz Yisrael on their own, without a formal schedule or tour guide. Someone close to the Rosh Yeshivah “tattled” on them and insisted he forbid them from traveling. The Rosh Yeshivah called them in and asked them about their plans.

He listened, and then offered his assessment. “It can be a wonderful experience or the opposite, it can be very dangerous — and I don’t know either of you well enough yet to be able to decide that, because it depends on the person. So what I would suggest is that each of you approach a beis medrash bochur who knows you well and discuss it with him. If he knows you, he’ll be able to guide you on whether or not the trip is right for you.”

He was building bnei Torah, and he was confident that his beis medrash bochurim, years in to the system, had already developed the sensitivity.

And somehow, mixed in with the prevailing message about being a ben Torah was the call to take achrayus, that being a ben Torah means caring for others as well.

He didn’t speak at conventions or, for that matter, didn’t really speak anywhere outside of his beis medrash. Yet like a devoted soldier, he participated in meetings for Torah Umesorah and Agudah, listening, guiding, showing his talmidim how one can lead without being visible.

In some yeshivos, Purim is a day to focus inward, for learning and personal growth, a time for private conversation and private joy. Other yeshivos see the potential for major fund-raising and send their talmidim out to provide a much-needed boost to yeshivah coffers.

Long Beach has its own minhag. The bochurim collect, a well-oiled operation which includes every talmid, with precise lists and routes for each group.

But here’s the catch: The money doesn’t go to the yeshivah.

The Israel Purim Fund provides checks for hundreds of yungeleit in Eretz Yisrael. Over the years, millions of dollars have been raised, but the rosh yeshivah who spearheaded and inspired the whole operation never got involved in who should receive or how much — leaving that to the roshei yeshivah in Eretz Yisrael to decide.

And the day after Purim? The beis medrash was full to capacity, as usual, the kol Torah echoing off its walls, the efforts and successes of the day before filed away, just part of the wider message.

And then, before the bochurim would leave for bein hazmanim, the Rosh Yeshivah’s shmuess always included something about raising money for Lev L’Achim, as he imbued his talmidim with achrayus for impoverished Jews — because whether that hunger was physical or spiritual, they were responsible to help.

The Rosh Yeshiva didn’t generally display emotion, preferring substance over style. But on Rosh Hashanah, his voice cracked with passion as he spoke of kevod Shamayim and the mandate to fill the world with His glory — reminding them that the majority of their own nation did not even know of the existence of the Creator.

That’s why his talmidim are not just bnei Torah, but in so many cases they’re also the board members, the chairmen, the committee heads — the ones doing the hard work to fill the world with kevod Shamayim, just as he taught them.

Never Say No Hope

There were two stages in the life of a Long Beach talmid.

The first few years were a time of reverence and awe, watching from afar, observing and soaking in the atmosphere. Then came the Rosh Yeshivah’s shiur, and their proximity to him not diminishing the reverence, but allowing for a more tangible layer of love.

And then, another aspect of the Rosh Yeshivah’s remarkable solidness and consistency became apparent to them: They suddenly understood that he’d do anything for them. He belonged to his talmidim.

It wasn’t only the shiurim and shmuessen; every conversation in learning was about prodding them, strengthening them, lifting them.

And when they came in to speak with him (after Purim each year, he stopped saying shiur, devoting those weeks instead to private appointments with the bochurim), they realized how well he knew them, how closely he’d been watching.

In private, words were used just as sparingly, but his voice, his expressions, his message was laced with love and confidence in them, his belief that they could make it in the real world — the beis medrash — because “the ikar is to sit and learn.”

He spoke kindly, but always with authenticity, the only real tool in his chest. A talmid once came to visit after several years in kollel, and shared his appreciation for Mishnas Rav Aharon, the sefer written by Rav Yitzchok’s rebbi.

The talmid rhapsodized about the clarity and depth, the dazzling lomdus and immeasurable bekius, and the Rosh Yeshivah listened.

“It’s not for you,” he said, unimpressed by the enthusiastic endorsement.

If it wasn’t what the talmid needed, then it wasn’t right.

He saw the individual within the context of the bigger picture as well. Those talmidim who’d suffered personal loss found that the Rosh Yeshivah had the capacity to deeply empathize and support, sharing their burden of pain. Those who came and shared private problems realized that he’d been carrying those issues along with them the entire time.

His wise eyes took it all in. The Rosh Yeshivah had notes of his shiurim, but they were for his own use, not for the public. Once, he realized that someone had photocopied one of the shiurim, and he was upset. In shiur, he asked that whomever had copied the shiur should please let him know — he didn’t want those pages to get out.

No one came forward, so the Rosh Yeshivah repeated the request the following day. Again, there was no response, and he let it drop.

Nearly two years later, a talmid came to say goodbye before leaving yeshivah for Eretz Yisrael, and after wishing him well, the Rosh Yeshivah made a request: “Can I have the photocopy of my shiur back? I’d really like to make sure it doesn’t get out.”

The talmid sat there stunned. “If the Rosh Yeshivah knew it was me who took it, why didn’t he confront me right away?”

And at that moment, the Long Beach rosh yeshivah pulled back the curtain on the process, just a bit.

“If I would have said something, you’d have been embarrassed in front of me and wouldn’t have been able to be mekabel from me. We would have lost the last two years of chinuch.”

That was one cheshbon, for one talmid. But in the clear, orderly mind of the Rosh Yeshivah, each talmid had a similar file.

Once, he called over one of the older, successful bochurim and asked this bochur about another struggling talmid.

“What do you think we can do for him?” the Rosh Yeshivah asked.

The bochur answered honestly, “There is no hope for him; I don’t think there’s anything we can do.”

Rav Yitzchok was upset. He stood up and pointed a finger at the bochur and asked, “If it was your brother, would you say those words? You can’t ever give up on a bochur.”

The years passed. The successful bochur continued to succeed, and he became an accomplished talmid chacham. Eventually, he applied for a position as a maggid shiur in a prestigious yeshivah, the Rosh Yeshivah backing him all the way.

He was seriously considered for the job, but he lost out to someone else — the second bochur, the one who’d struggled alongside him at a different time.

When Rav Yitzchok heard, he laughed. “You see?” he gently asked his talmid, “Can you ever say a bochur has no hope?”

On Purim, the Rosh Yeshivah tried to dance with each bochur individually, and perceptive talmidim noticed that he held on to the quieter, more bashful bochurim for longer, using the dance to convey his appreciation for them, even if they weren’t yet blessed with the confidence or self-assurance to stand out.

He tried to walk each and every bochur out of his house after their appointment was done, a quiet gesture of respect.

It was the way he listened as they spoke — elegant, kind, and so insightful. Even long out of yeshivah, talmidim came with their questions, knowing that he would quickly discern the heart of the issue: He addressed their concerns — in business, in chinuch, in life itself — and while he often took pride in their accomplishments, the only real way to impress him was with being alive in learning.

Inevitably, it came down to that. Voss hert zich mit di lernen? Der ikar iz lernen.

Gevaldig

Then came the stroke, and incapacitated, another layer fell away. No longer concealed, his love for them was readily apparent.

His eyes flashed with joy when he saw them, his one working hand conveying obvious affection and appreciation. Eventually, he lost most of his speech, able to say just a single word.

“Gevaldig, gevaldig, gevaldig,” he would say, the last word he had left.

It wasn’t just a rote expression that remained with him, the sound his body produced by inertia, but rather, an echo of a career spent prodding talmidim to greatness.

It was a single word that allowed him to continue with this mission, to keep doing that which had been done for him, to build bnei Torah.

His rebbi, Rav Aharon, had been trained in Slabodka — factory of “gadlus ha’adam — the majesty of man.”

Rav Yitzchok reflected that: impeccable in action, impeccable in conduct, and impeccable in modesty, so that the Torah he taught stayed untainted by ego or self-interest.

And at the end, that’s what remains: The “reine Torah,” the pure Torah of the Long Beach rosh yeshivah and of the army he created.

Yehi zichro baruch.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 871)

Oops! We could not locate your form.