Rock Star

| April 30, 2024Under Monsey's sprawling yards lies a treasure of volcanic lava

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

S

ay the name “Monsey” and images of suburbia come to mind. But Heshy Friedman knows something that most others don’t about his hometown: Beneath its rolling lawns and leafy trees, small parts of Monsey and its environs are built on volcanic rock, which holds a literal treasure trove of minerals and geological gems just waiting to be discovered.

A quick glance at the path leading to the Friedmans’ home is all it takes to differentiate it from the rest of the high ranches on the block. Instead of a neat grassy lawn or decorative shrubs, an assortment of irregularly shaped rocks line the walkway to his front door. Walk into Friedman’s home, and it’s immediately clear that this house is anything but typical.

The lower level is comprised of several rooms, each of which is at least partially dedicated to his extensive mineral collection. A guest bedroom houses a small breakfront, but instead of displaying crystal decanters or silver candlesticks, the lighted cabinet is filled with small, mostly white, cotton-lined boxes. Each contains at least one mineral, although a few hold several smaller specimens clustered together.

There must be dozens of minerals of all sizes and shapes in that breakfront: sparkling purples and pale greens stand out amid varying shades of white, grey, and amber. While some minerals are smooth, most are jagged, with otherworldly protrusions varying in texture and shape. Each box has a label identifying its type, where it was unearthed, and whether it was something that Heshy discovered on his own or acquired from another collector.

All of them are volcanic rock, found within a 50-mile radius of the Friedman home.

Buried Treasure

Pointing to a specimen, Heshy starts educating us about its pedigree.

“This one is from an old quarry in Paterson, New Jersey,” he tells us, holding a chunk of pectolite in his hands that dates back to the late 1800s.

This isn’t the oldest in Friedman’s collection — he has several that were formed decades earlier, according to the timelines determined by geological maps that estimate the date of the rock they were found in.

“Scientists attribute age ranges that are an obvious contradiction to the age of the earth from a Torah perspective to various rock types,” explains Heshy, who notes that the Flood in the times of Noach, and even Maaseh Bereishis, may have stressed the rocks in ways that make them seem millions of years older than they actually are.

Heshy shows us samples from Prospect Park, New Jersey, about 30 minutes from Monsey, and others from Haledon, Millington, Bound Brook, and Montclair, all located in northeastern New Jersey. He opens multiple drawers in the lower portion of the breakfront, each of which is filled with more small white boxes containing more treasures.

And that was just the first room.

Down the hallway is Heshy’s office, which also showcases more minerals. Painted Tiffany blue, the room contains a bookcase with seforim, a computer desk, and a printer, and its walls are decorated with his semichah certificate, as well as diplomas issued to him and his wife Avigail. But it is clearly the minerals that are the main attraction, and they are significantly larger than the specimens we saw just a minute ago. Reaching up to the top of the bookcase, Heshy takes down a large crystallized hunk of amethyst topped with a single calcite crystal. The entire piece measures approximately twelve by five-and-a-half inches and weighs more than seven pounds. According to Heshy, any museum would be proud to display it prominently in their collection.

He holds up another amethyst.

“If this was Brazilian, it would be worth $20 or $30 because Brazilian amethysts are a dime a dozen,” Friedman says. “Being that this is from New Jersey, it is very valuable even though the color isn’t great, because it is rare. Locality is very important when it comes to minerals.”

The room’s closet is fronted by a set of sliding closet doors, which contain long, flat boxes filled with surplus minerals that Heshy occasionally sells at collector shows.

“Deep brown STILBITE Prospect Park New Jersey $16,” reads the label on one box of small rocks.

“AGATE Southbury, Connecticut $5,” reads another, while a tag identifies a larger chunk of brown rock topped with irregular whitish crystals as laumontite, also from Prospect Park, priced at $20.

Pretty much every closet in the lower level of Friedman’s home is similarly filled with boxes of rocks. Instead of exploring those, Heshy suggests we move on to the garage, which is where the bulk of his collection is located.

Crystal Clear

To be fair, many people don’t use their garages for their cars, so it comes as no surprise that in addition to housing a succah and a spare refrigerator, the Friedman’s garage devotes significant space to the mineral collection. A low white laminate cabinet has rows of drawers (36 to be exact) which are filled with minerals of every size, shape, and color. Next to it, several plastic storage units with drawers are stacked on top of each other and by now, I don’t even need Heshy to tell me what is inside each one.

Proudly displaying his specimens, Heshy nonchalantly tosses out names of minerals like glauberite, pectolite, and datolite, leaving me feeling like I failed high school Earth Science. He shows us a sample of pale green prehnite whose protruding growths look like chubby fingers. One of the fingers broke off and had been epoxied back on; Heshy assures us that fixing a specimen is accepted practice, as long as it is subsequently labeled as repaired, even though there are no visible gaps, color stains, or shines from the glue. We see spiky natrolite, and magnetite, the purest iron ore, which is strongly attracted to magnets.

I feel a little less overwhelmed when Heshy pulls out a large chunk of graphite that comes from Stony Point, New York, which is known for its high-quality crystals and is just ten miles from his home. Given our familiarity with graphite’s use in pencils, Heshy grabs a piece of cardboard and demonstrates how his specimen is equally capable of leaving its mark.

A quartz crystal from upstate New York’s Herkimer County, approximately 80 miles northwest of Albany, was another item that wasn’t new to me. Often quite large, these crystals grow in pockets that exist within a rock known as dolomite, and their crystal clear appearance has earned them the name Herkimer diamonds. A friend who owns a home in the Herkimer County area presented Heshy with an opportunity to go digging on his own, and he shows us his find: a sample that is about four to five inches across and three inches high. Heshy estimates that this particular chunk of quartz would probably fetch a price of about $300 on the resale market.

The collection is a journey through time, with some specimens discovered recently, while others are more than 100 years old, including a dark green chunk of serpentine found 60 feet below New York City’s stock market in July 1902. Also of interest are two narrow pieces of agate, a type of quartz known for its signature banding that comes from one of the frum neighborhoods in nearby Suffern. From the outside, it’s hard to determine what an agate looks like, but a “window” on its outer surface can sometimes offer a glimpse of what lies inside. The stones are typically split or sliced before being polished to a smooth texture and like a grab bag gift, their contents can be hard to judge in their natural state.

“You never know what you will get from the outside,” says Heshy, showing us two halves of a single piece of agate that was divided vertically down the middle. The stones are near mirror images of each other, parts of the veining matching up exactly, while other portions vary from one side to the other.

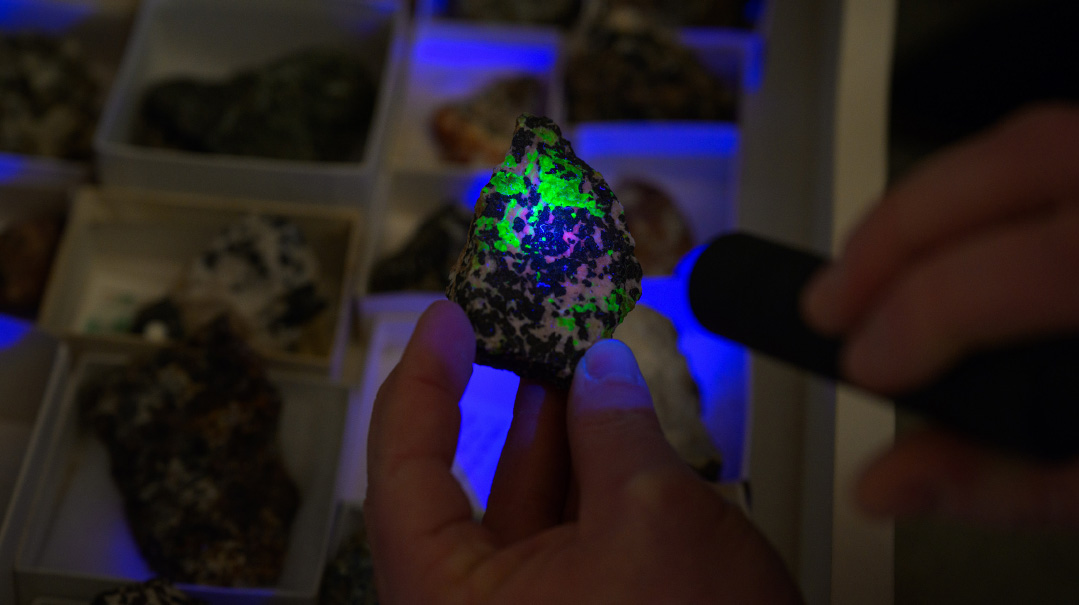

But by far the most fascinating were two crystals mined from Sterling Hill, a mine in Franklin, New Jersey, known for its fluorescent minerals. Under regular light, they look like unremarkable rocks: one an unremarkable beige, and the other an ordinary white. But once all the lights were turned off and Heshy flicked on a shortwave ultraviolet light, they glowed spectacularly, with bursts of neon green shining brightly amid flecks of fuchsia and bright blue.

“I know what they are without the UV light,” explains Heshy. “When you find them, they are dirty, big pieces, and you might have to break them down and sometimes soak them in acid.”

Those acid baths are par for the course for Heshy, who uses the technique on some of the minerals he unearths.

Out of Site, Out of Mine

Heshy’s interest in rocks started when he was seven years old and living in the Concord section of Monsey. He and his father would often go hiking in nearby Harriman State Park, home to multiple abandoned iron mines, most notably the Revolutionary War-era Bradley Mine, which ceased operations in the late 1800s. Father and son loved to explore, and they frequented the Hogencamp Mine. They would wander around the pits and sift through the dumps — piles of discarded material by left behind by miners — and Heshy’s rock collection began with some of his more interesting finds from those outings.

Heshy’s father wasn’t the only adult in his life who had an interest in geology. Neighbor Avrohom Rosenberg (of Tzlil V’Zemer Boys Choir fame) enjoyed showing his young friend his collection, which included Brazilian amethysts and other unusual pieces. Heshy’s fascination with rocks and minerals grew as he did, and as a teenager, he would go to old mines and regional mineral shows. Both helped him gain experience and grow his own collection, which by then contained specimens from all over the world.

But Heshy realized that while anyone could have a collection, you needed to specialize to stand out from the crowd. The choice was obvious — in addition to living near Harriman State Park and the many mineral-rich locations in northern New Jersey, he knew something that most of his friends and fellow collectors didn’t.

“Most people don’t realize that there is volcanic rock here in the Monsey area,” explains Heshy, who began focusing his attentions on minerals of southern New York and Northern New Jersey.

As his collection continued to expand, Heshy decided to organize it into a database, which would include detailed information about the minerals he had acquired. Eventually, he realized that his database could be useful to others and he posted it online, launching his website, minerals.net, in 1997. Heshy’s other hobbies — nature photography and hiking — have played a significant role in his passion for mineralogy, and the various rooms of the lower level of his Monsey home bear testament to his efforts, housing several thousand specimens sourced from the mineral and gemstone kingdom.

Heshy’s wife admits that she knew somewhat about her husband’s passion for minerals before they got married.

“We went on a date to Sterling Hill Mine and I got a two-hour tour of some of the collection,” says Avigail Friedman. “I don’t think I knew exactly how big this would be, but I had an inkling.”

The Friedmans’ five children have all accompanied their father on his excursions to old mines and construction sites. At least three of them seem to follow in their father’s footsteps, joining the very short list of Orthodox Jews who are deeply entrenched in the world of mineral collecting. And while people have different opinions about Heshy’s rather unusual hobby, the response to the size, variety, and beauty of his collection is nearly universal.

“The most common overwhelming reaction is that they cannot believe that the minerals — their crystal shapes and colors — are 100 percent natural and the way Hashem created them,” notes Heshy.

Ironically, Heshy’s business evolved out of his passion for his hobby. He used the experience he gained creating minerals.net to launch his career; his Azurite Marketing company creates websites and provides marketing for professional companies and organizations.

Rock of Ages

The formation process of the minerals Heshy collects is incredibly complicated. The complexity of geology is part of Maaseh Bereishis, and each of the three types of rock — igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic — contain different minerals that can develop in a variety of ways.

Much of the volcanic rock Heshy owns comes from basalt, which is rock formed by solidified lava that hardened as the earth was created and expanded. As the rock stretched and cooled, air pockets formed throughout. The chemical elements inside these pockets crystallized and grew, forming the structures that mineral collectors like Heshy continue searching for today. In places where hot lava flowed into water, significantly increasing its temperature, larger air pockets were created in the underlying rock, and larger crystals formed in those cavities.

Sedimentary rock is formed in unaltered layers and includes rocks such as shale, slate, and limestone. While the sedimentary rock of the Catskill Mountains, for example, has hardly any mineralization, other locations have fared differently, with minerals formed when certain conditions are met. Perhaps the most commonly known mineralization in sedimentary rock are the spectacular formations that can be seen in caves, where dripping water picks up both calcium and carbon as it passes through the rock. As the water evaporates, calcium carbonate is left behind on the caves’ ceilings and floors, accumulating over time into stalagmites and stalactites. In metamorphic rock, which is subject to heat and pressure, the components of the actual rock react to those changes, forming it into minerals and crystals.

“When Hashem created the world, the same diversity that is evident in fauna and the flora was also created within the mineral part of the world,” explains Heshy. “There are different rock types, with different solutions that formed into different crystals based on different environments. It’s all created by Hashem.”

Digging Deep

The key to finding minerals is knowing where to look, and Heshy’s collection bears testament to the many locations within 100 miles of his home that are just ripe for the digging. In addition to doing well in northeastern New Jersey, the northern counties of Orange, Ulster, and Sullivan, have all been well worth visiting, with Harriman State Park, Ellenville, Wurtsboro, and Amity all yielding exciting finds. Tiny Rockland County, where Monsey is situated, has also been an excellent source, and Heshy does well in nearby areas including Wesley Hills, Suffern, Haverstraw, Stony Point, Rockland Lake, and the Ramapo Mountains.

Mineral collectors often frequent quarries on weekends when they sift through excavated materials looking for finds, although it can sometimes take considerable effort to find the proverbial diamond in the rough. Construction sites can also be veritable gold mines for rock hounds, and living as close as he does to the Monsey area’s prime location for minerals, nothing excites him as much as seeing a project going up in that zone.

“When I dig on my own, I can only get surface area, but when they dig sewer trenches or foundations, they go five to ten feet deep,” notes Heshy. “When they pull up big shovelfuls of dirt, you just want to get to that pile. When I see something white, I don’t necessarily know what is there, but I know it will be good and I just toss it in my bucket to look at later.”

Heshy just smiles when I ask him if he has an interest in moving to the part of Monsey where the mineral hunting is productive. For now, he is content to remain with his collection in a locale which has only fossils, yielding fossilized coral and teeth but no minerals.

Some of Heshy’s favorites minerals include prehnite, magnetite, stilbite, pyrite and graphite, as well as New Jersey amethysts and Herkimer diamonds. While he marvels at the unique natural shapes of his finds, on other occasions, he has altered some of them and has made cufflinks out of polished cabochons. Heshy readily admits that trimming a mineral specimen is a risky business that can sometimes backfire when things don’t work out as planned, but he has done well with buying less expensive pieces that seem to have potential, knowing that proper trimming will increase their value.

Tools of the Trade

Invariably, finding minerals is a labor-intensive process. It takes a good eye to spot anything of value, and Heshy sets out on his trips armed with a Home Depot bucket or two, a hammer and a chisel, and occasionally a rock pick and a crowbar (the notion of finding a mineral just lying on the ground waiting to be picked up is almost always wishful thinking). A sledgehammer gets thrown into the bucket when Heshy suspects the dig might take more effort.

Heshy tosses whatever seems to be of value into his bucket and brings them to his backyard, where he sorts everything out on a plastic folding table. Anything cuttable or polishable is hosed down before being cleaned up with an electric toothbrush or a high-pressure water gun. The rest finds its way to his backyard dumping ground, although some specimens have been taken around to the front of the house to line the path to the front door.

His collection is always a conversation piece for guests. On one occasion, a friend who had come for a Shabbos meal came back to the Friedmans’ house with his daughter, who was carrying a rock and seemed none too pleased to be coming along for the visit.

“He told me, ‘My daughter wants to return this, she took it on her way out,’” recalls Heshy. “To be honest, she didn’t look like she really wanted to return it.”

Heshy’s backyard is home to the largest items in his collection. He has a 40-to-50-pound piece of prehnite that was discovered some 50 or 60 years ago when workers were blasting through rock to build Route 80 in Paterson, New Jersey. He describes an 18-inch chunk of magnetite that he found near Bear Mountain as “super heavy,” estimating its weight at 50 pounds.

“It’s pretty big,” notes Heshy. “Don’t ask me how I carried that one.”

A Breastplate of Gems

Given his fascination with the earth’s rocky treasures, it should come as no surprise that Heshy has a particular interest in the gemstones that were included in the Choshen that was worn by the Kohein Gadol. He has authored numerous articles on minerals and gemstones and is currently working on one that discusses the Choshen and what stones it might have included. While the Chumash enumerates all 12 stones in parshas Tetzaveh — odem, pitdah, barekes, nofech, sapir, yahalom, leshem, shevo, achlamah, tarshish, shoham, and yashfeh — the identity of those gems has long been up for debate, since translating them according to contemporary knowledge isn’t necessarily accurate.

“It has to be in context of availability of those gemstones in the ancient world and their locations,” notes Heshy. “For example, people say that sapir is sapphire, but the ancient sapphire was a mineral called lapis which was found in mines in Afghanistan thousands of years ago.”

With the Luchos carved out of sapir as well, that explanation seems to fit.

“You can’t really carve sapphire,” says Heshy. “It is too hard and too brittle. Lapis is softer and very carve-friendly.”

Similarly, while contemporary texts define yahalom as a diamond, not all meforshim agree that there was a diamond on the Choshen. Other stones, like the achlamah mentioned in the Chumash, are less controversial, with most of the commentaries agreeing that it is amethyst.

So while the Choshen had 12 stones, one for each of the Shivtei Yisrael, Heshy’s planned collection of its stones will have a different number.

“I’m going with all the meforshim — Rav Saadiah Gaon, Chizkuni, Rabbeinu Bechaye — and bringing all of them down. Since everything is machlokes, I’m taking a consensus of most poskim and will have a lot more than 12 stones.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1009)

Oops! We could not locate your form.