Retell the Story

| April 9, 2024The world’s largest collection has 8,500 of them. Which Haggadah are you going to use this Pesach?

It’s a favorite collector’s item, and for good reason: In the two thousand years since the oral tradition of the Exodus was recorded in the form we’re all familiar with, the Haggadah has become the world’s most widely published Jewish text. The world’s largest collection has 8,500 of them. Which Haggadah are you going to use this Pesach?

W

hich Haggadah will you use this Pesach? Do you choose the same one year after year, every wine stain evoking a memory? Or do you enjoy a different Haggadah with a new peirush every year?

Whatever your preference, you have plenty to choose from. In the nearly two thousand years since the oral tale of our people’s salvation was recorded and took the form we’re so familiar with, the Haggadah has become the most widely published Jewish text. First handwritten and illustrated, then printed, the Haggadah has followed the Jewish People throughout the long journey of exile.

The National Library of Israel (NLI) houses the largest collection of Haggadahs in the world. Its 8,500 traditional Haggadahs — manuscripts, printed texts, scanned works — date from before the invention of modern printing up until today, and come from every part of the globe.

Let’s open some of these treasured Haggadahs of the National Library. We’ll move with them through the time and space that make up our people’s history since we were freed from slavery thousands of years ago to become Hashem’s nation.

Shadow of the Crusades

Rothschild Haggadah (Italy, 1450)

The National Library of Israel inaugurated a new building after Succos last year, but the scheduled gala opening was canceled due to the war. Without fanfare, the stunning new facility was opened to the public. But five items considered absolutely irreplaceable — including the Rothschild Haggadah — have been kept in safety storage, until the war’s end. If the Rothschild Haggadah could speak (pun intended), it might say that this wasn’t the first war it has faced.

Handwritten in Italy in 1450, the Haggadah became famous when it was bought late in the 19th century by Baron Edmond de Rothschild, known as “the Benefactor,” for his contributions to building up Eretz Yisrael. After his death, his son James in England inherited it. Unfortunately, before World War II, James sent the Haggadah to France. When the Nazis conquered France in 1940, they seized it, along with innumerable Jewish treasures, and took it to Germany, intending it to be part of their plan to build museums to retain the memory of the Jewish people they wanted to, chas v’shalom, wipe out.

Details of the Rothschild Haggadah’s postwar whereabouts are sketchy. In all likelihood, an American soldier rescued it. In any case, it ended up at Yale University, donated by an alumnus who bought it. In the 1980s, attempts to return looted artifacts bore fruit, and the Haggadah was returned to the Rothschild family, who donated it to the National Library of Israel.

The Rothschild Haggadah’s beautiful illustrations call to mind tribulations of earlier exiles. In the section of the Four Sons, there is a puzzling picture next to the Wicked Son, the rasha: A clean-shaven armored knight is clutching a small child in one hand, and in the other he is raising his sword. Though the chilling illustration has faded with time, at the feet of this clearly non-Jewish crusader, we see a Jewish man, kneeling. What is happening here? Is the Jew surrendering himself and his child to the crusader’s faith? We don’t know, but what is clear is that the 15th-century illustrator of the Rothschild Haggadah was working within living memory of the Crusades.

To recall Pharaoh’s command to throw Jewish male infants into the Nile, the Rothschild Haggadah illustrator created a terrifying picture of an Egyptian dressed in red drowning two babies. The red ink has spread “out of the lines” of the Egyptian’s clothing. This was probably a natural effect of the ink ageing on the parchment over centuries, but today it reminds us of the blood spilled in ancient Egypt, and of the plague of blood that spread to the Nile itself.

The words of Vehi She’amdah remind us that the war against our people has been fought in every generation: by Pharaoh, by Crusaders, by Nazis, and today, by Hamas, Hezbollah, and their supporters.

For now, the Rothschild Haggadah is sheltering in its miklat — like so many of our people who have found safety in their shelters during the present war. But every word of the Haggadah assures us that ultimately the enemies will fall and we will win. V’HaKadosh Baruch Hu matzileinu mi’yadam.

And when that happens, the Rothschild Haggadah will be taken out of storage to be proudly displayed in its true home, in Yerushalayim.

Maxwell House Haggadah (New York, 1932)

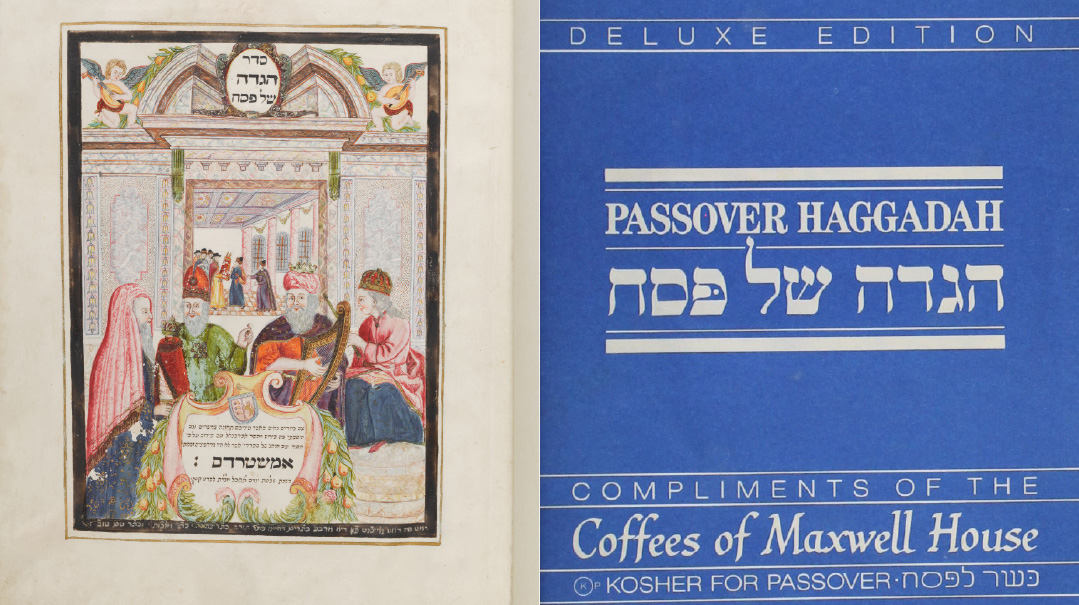

Amsterdam Haggadah (Holland, 1695)

If you can recall a Pesach Seder in the US from the middle of the 20th century, you might well remember using one of those ubiquitous Maxwell House Haggadahs. Since its first publication in 1932, over 60 million copies have been distributed — and you can still get them for free today in some grocery stores before Pesach. That makes the Maxwell House Haggadah the most widely disseminated of all time.

The NLI doesn’t display any of their 30-some Maxwell House Haggadahs, since they are the opposite of rare. But they do display, in their permanent exhibit hall, a Haggadah printed in Amsterdam in 1695 that influenced the Maxwell House Haggadah.

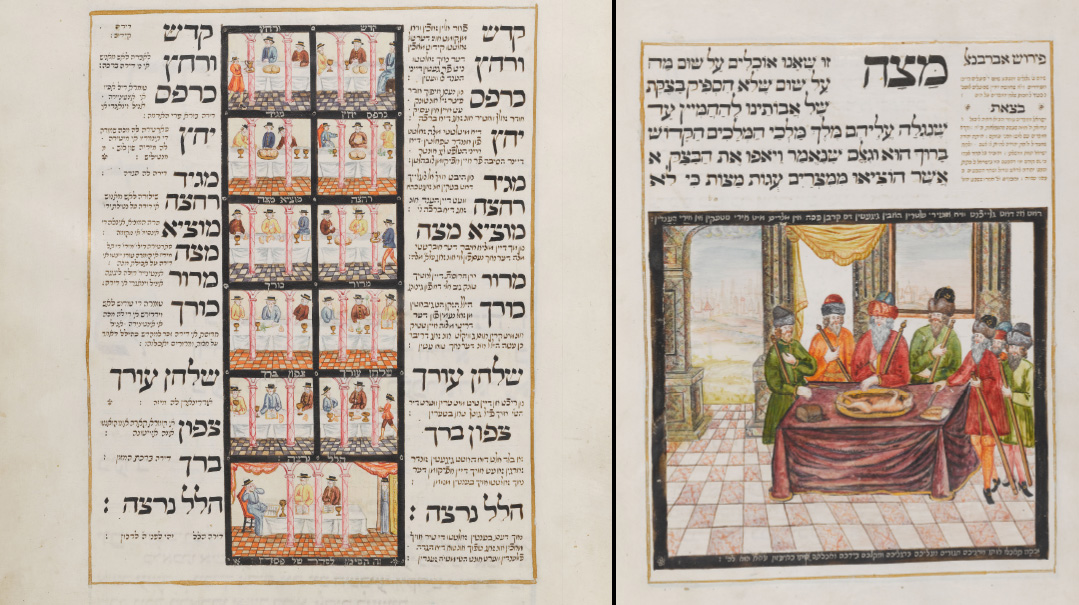

Printing began in the West when Johannes Gutenberg invented his press in Mainze in 1440. It didn’t take long for Jewish texts, including Haggadahs, to be printed instead of handwritten. In 1695, two Jewish printers printed the Amsterdam Haggadah with a new font called “Otiyot Amsterdam.” Clear and easy to read, the new typeface became an instant success. For hundreds of years, printed Haggadahs — and even some handwritten ones — used this same lettering.

It’s unlikely that the advertising agency artists who created the Maxwell House Haggadah as a marketing tool to sell kosher l’Pesach coffee were familiar with the Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695, but they certainly recognized Otiyot Amsterdam, which had been used in a variety of Haggadahs for hundreds of years. Not surprisingly, they chose it for what would become the most widely circulated Haggadah in history.

But the 1695 Amsterdam Haggadah isn’t only famous for its influential lettering and its ability to help sell coffee hundreds of years after it was printed; it was the first Haggadah to include copper-engraved illustrations. Those illustrations were themselves copied extensively — including in the first edition of the Maxwell House Haggadah.

The illustrator credited on the cover of the Amsterdam Haggadah is “Avram Bar Yaakov, from the family of Avraham Avinu.” Bar Yaakov was a ger, a former priest from Germany who converted to Judaism and whose work would have a lasting influence on the look of Haggadahs.

Perhaps Bar Yaakov’s unusual background enabled him to create another first in the Amsterdam Haggadah: two fold-out maps, appended to the end of the text. With this rare feature, Bar Yaakov created some of the first Hebrew-language maps ever, though they were based on works by non-Jewish cartographers — maps that Bar Yaakov was presumably familiar with from his earlier days as a priest.

The first map tracks the Jews’ long trek through the desert from Egypt to Eretz Yisrael, listing all the stops in the 40 years in the desert, enumerated in parshas Masei. The second is a map of Eretz Yisrael itself, divided according to the nachalos of the shevatim. At the bottom of the second map Bar Yaakov included illustrations and pesukim. For example, under a picture of a commanding bird with wings outstretched, he cites the famous pasuk from parshas Yisro about Hashem bringing His people back to Eretz Yisrael on the wings of eagles. In another picture, cattle graze and sip from a stream marked chalav — milk; nearby, a small building houses beehives, next to the word dvash, honey. Together, they make a clear visual reference to the Land of Milk and Honey.

Bar Yaakov’s maps, like the text of every Haggadah, tell the story of the Jewish People’s journey — from Canaan to Egypt, to the desert, to Eretz Yisrael. A German convert illustrated a work printed in Holland that inspired a New York Haggadah distributed all over the United States hundreds of years later.

First off the Presses

Guadalajara Haggadah (Spain, 1482)

Zevach Pesach (Italy, 1505)

The oldest printed Haggadah in the world, the first not to be handwritten, was published in 1482 and is known as the Guadalajara Haggadah. The National Library of Israel houses the one and only copy that has survived through time.

Books printed in the first half-century after the invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century are known as incunabula, which literally means “cradles.” A book written by scribes would be rare by definition; printing a book produces multiple copies. That’s why more than one copy of printed books, even of the early incunabula, often exist.

Unless, however, the book was printed, as the Guadalajara Haggadah was, in Spain, in 1482 — a mere decade before the expulsion of Jews from that country. Most of the printed copies of the groundbreaking 1482 printed Haggadah were presumably destroyed or lost, leaving only this one copy.

The Guadalajara Haggadah itself is quite simple and unadorned, especially compared to earlier handwritten illuminated texts. Though the print is clear, it is simply the text of the Haggadah, without any pictures at all. The text is set in two columns, without spaces between sections, and without nekudos — vowels.

The modest Guadalajara Haggadah shares pride of place in the NLI display case with many more elegantly decorated and illustrated Haggadahs, for three reasons. First, it is one-of-a-kind, unique. Second, it was a first, in that it was the first to be printed. And third, it was a last… a final memory of Pesach Sedorim held in a land that persecuted and expelled its Jews.

But as so often happens in Jewish history, the end of an era opened up new possibilities. Out of Spanish persecution, another Haggadah was born: Zevach Pesach, the first ever printed with a commentary, the peirush of Rav Yitzchak Abarbanel. He completed the commentary Erev Pesach 1496 and published it as part of a Haggadah in 1505.

Born in Portugal to a distinguished family descended from Dovid Hamelech, the Abarbanel served in ministerial positions in Portugal, Spain, Naples, and Sicily. He was exiled from the first three lands, each time losing all his possessions. He was advisor to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, who finally expelled the Jews. They offered to exempt him from the decree, but he chose to depart with his people on Tishah B’Av 1492 — just days before Christopher Columbus embarked on his voyage to the New World.

The Abarbanel wrote commentaries on numerous seforim, posing many questions in his introductions that his peirushim would answer. These introductions also include personal memories, descriptions of his many exiles, and allusions to verses in Tanach in almost every sentence. Given his hardships in life, it’s no surprise the sefer he cites most often is Iyov.

The NLI possesses a copy of the Abarbanel’s innovative Haggadah. It opens with 100 questions, which he calls “shearim,” citing the famous pasuk about Yitzchak Avinu reaping 100 times what he sowed. Abarbanel’s peirush did, indeed, multiply a hundredfold: numerous later Haggadahs, including the 1695 Amsterdam Haggadah, include his commentary.

Almost 400 years after the Abarbanel published his groundbreaking Haggadah, Yosef Chazanovitch, a doctor in Odessa in the late 19th century, and an ardent book collector, had an inspiration. He wanted to open a library that would house all the texts of the Jewish People. And he wanted it to be located in Jerusalem.

Chazanovitch sent his collection of 10,000 books to create the foundation of the first national library of the Jewish People. It opened in 1892, exactly 400 years after the Spanish expulsion in which the Abarbanel lost his home — and his books. The name of the library? Midrash Abarbanel. It would become the precursor to the National Library of Israel.

They Stand Up to Destroy Us

Gurs Haggadah (France, 1942)

The Gurs Haggadah is very different from all the others profiled here. Written in the 20th century, only five pages long, handwritten on cheap paper in a faded, cramped script. Just one illustration, a sketch of a ke’arah, a Seder plate, a washed-out, black-and-white picture a child might have drawn.

The story of the Gurs Haggadah begins in 1940, when the French surrendered to Nazi Germany. The Vichy government detained Jews fleeing Germany and interned them in the Gurs detention camp in the mountains of southwest France. Conditions there were brutal. In the winters of 1940 and 1941, about 25 people died every day of hunger, disease, and exposure. Many survivors were later sent to their deaths in Auschwitz.

Rabbi Leo Ansbacher was born in Frankfurt, Germany. In 1933, when the Nazis rose to power, he and most of his family fled to Belgium. But when the Germans occupied Belgium and began rounding up Jews, Leo and his brother Max were put on trains marked “Traitors” and were sent to France, eventually to Gurs.

Despite the horrific conditions, Rabbi Ansbacher and others tried to inject Yiddishkeit into the camp. With just a few siddurim available, the young rabbi led davening and others would follow, word by word. He established a small beis medrash that inmates nicknamed Yeshivas Bnei Barracks, and helped create a girls’ “youth group” called Menorah to teach Hebrew and basic tefillos.

At the beginning of 1941, an inmate named Aryeh Ludwig Zukerman, with Rav Ansbacher’s help, began to handwrite a Haggadah — from memory. Because paper was so hard to come by, the Haggadah had to be written with small, cramped Hebrew letters. To save time and help the many assimilated Jews who couldn’t read Hebrew, Rav Ansbacher added transliterations of the songs of Nirtzah that end the Seder — produced on a camp typewriter.

A local rav from a nearby town managed to send in enough flour to bake matzos and he made copies of the handwritten Haggadah. And so the Jewish prisoners of Gurs were able to have a Pesach Seder led by Rav Ansbacher — for many, the final Seder of their lives.

The stunning Rothschild and simple Gurs Haggadahs offer many contrasts — but they have one important thing in common. Both give testimony to Hashem’s Hashgachah, which has ensured Jewish survival in every generation. “Shelo echad bilvad amad aleinu l’chaloseinu…. v’HaKadosh Baruch Hu matzileinu miyadam.”

Crowned like a Queen

In Pirkei Avos, Rabi Shimon describes three “crowns”: that of the Torah scholar, that of the Kohein, and that of the king. Famously, though, he adds the highest crown: “the crown of a good name.”

A Haggadah printed in Amsterdam in 1738 includes on its title page a lavish illustration of the pasuk. The crown of Torah, worn by a talmid chacham, looks like a tallis over his head; the keter Kehunah shows a man adorned with an elaborate headdress, wearing the Urim V’Tumim; a man strumming a lyre wears a shining crown — clearly a reference to Dovid Hamelech.

And the “keter shem tov,” the crown of a good name? Perhaps unexpectedly, in a Haggadah close to 300 years old — the crown that tops them all is worn by a woman. Can we assume she earned her “crown” for a month of Pesach preparations?

Floating Down the Canal

Another woman wearing a crown shows up in that same 1738 Amsterdam Haggadah, in a picture of Pharaoh’s daughter spotting baby Moshe floating in a teivah on the Nile. Like many illustrations in early Haggadahs, they make no attempt at historical realism in depicting ancient Egypt. Pharaoh’s daughter and her handmaidens are dressed like Dutch aristocrats, and the mighty Nile River resembles a placid Amsterdam canal.

Ceremony of Separation

His powdered hair and three-cornered hat make him look like an 18th century Dutch gentleman, but his actions are familiar to 21st century readers. The illustration for the Havdalah ceremony shows a man sitting in front of a candle, holding up his fingernails to the burning light.

A Jewish Nose Knows

We usually associate puns with words, but who says an artist can’t play the same game? Two Haggadah illustrators used pictures to make visual puns.

In the Rothschild Haggadah, the Wise Son, the chacham, seems to be pointing to his nose. The response to the chacham’s question begins with the word “af,” meaning “so,” but the picture reminds us that af also means “nose.” A Jewish nose knows….

Researchers at the NLI were puzzled by a picture in the Prague Haggadah, printed in 1526. A hunter on horseback, holding a horn — and not a shofar — chasing a group of fleeing rabbits. Definitely not pshat…is this based on some kind of obscure midrash?

Nope — scholars realized that the picture is an elaborate pun. The German term for rabbit hunting is “jag den Hase.” Say it fast and might sound like yaknehaz, a mnemonic for recalling the proper halachah order of Kiddush and Havdalah when Pesach comes out on Motzaei Shabbos.

Rabbit stew is definitely not kosher for Pesach — or any other time — but if you follow these hares into their rabbit hole, you’ll get the Seder started on the right foot.

Many thanks to the staff at the National Library of Israel for their help researching this article.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1007)

Oops! We could not locate your form.