Remnant of a Generation

| January 4, 2022In tribute to Rav Shmaryahu Shulman

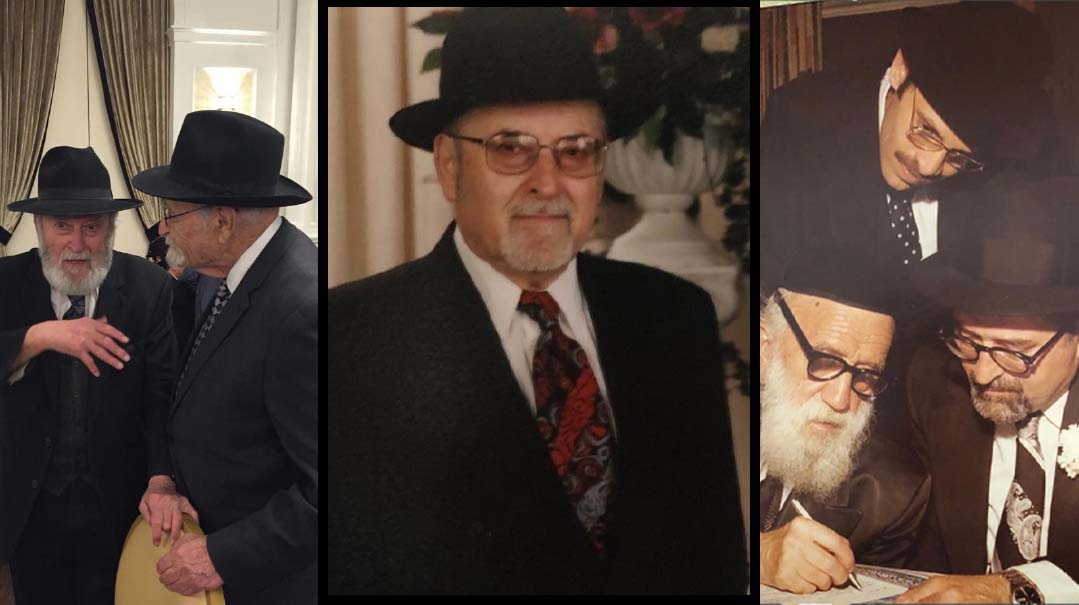

He wasn’t known among the ranks of gedolim or roshei yeshivah, and his picture isn’t hanging in living rooms around the world. But nonetheless, Rav Shmaryahu Shulman was a towering Torah giant whose life of close to a century was defined by limud haTorah, hidden behind the unassuming facade of simple stock broker.

Reb Shmaryahu, who passed away a few days before Chanukah, was renowned as a genuine “Shas Yid,” a prolific mechaber seforim and one of the last remnants of a generation that has long passed, a man greatly admired by gedolei Yisrael already 70 years ago, whom Rav Moshe Feinstein referred to as Hamaor Hagadol and whom he addressed in many of his teshuvos.

While I was only zocheh to know him for the last five years of his life, a chance encounter on a Friday night developed into a relationship for which I am forever grateful. Being connected to a talmid chacham of such stature and a link to a different generation was priceless. Stories of gedolim I had read as a child were substantiated after meeting someone who actually knew them. They were no longer names from a book or pictures on a wall, but real live people Rav Shulman would talk about as if he saw them yesterday.

Rav Shulman was one of the early talmidim of Rav Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman, from whom he received semichah, and was one of Rav Aharon Kotler’s first talmidim in America. He recalled as a youngster seeing Rav Elchonon Wasserman Hy”d on his visit to America in the late ‘30s, and another fond memory was when he, along with three of his friends, were awarded a cash prize from Rav Eliezer Silver upon Rav Silver’s visit to Ner Israel in 1942. He recalled hearing a shiur from Rav Yitzchak Herzog, the chief rabbi of Israel, about whose brilliance Rav Ruderman raved. He would often speak in learning with Rav Michoel Forshlager, the talmid muvhak of the Avnei Nezer of Sochatchov, who somehow found himself in Baltimore. As he left yeshivah, he developed close relationships with Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, and Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveichik.

Once he left yeshivah, he served as rav in the Kesher Israel and the Shomrei Shabbos kehillos in Washington, D.C., in Jersey City, and in Norwich, CT. When he joined the Agudas Harabbonim while still a bachelor, he was the youngest member and one of the only American-trained rabbanim. He would say that he only got in due to the recommendation of Rav Naftali Riff, and even so, he was given a bechinah by Rav Yehuda Leib Zelcer before being admitted.

His first sefer, Be’er Sarim, was published when he serving as a rabbi in Jersey City. For nearly every topic covered in the sefer, he would hop on the ferry and head over to the Lower East Side to discuss the inyan with Rav Moshe Feinstein. “It was amazing,” he would say. “He was holding in every sugya like he saw it yesterday.”

(Rav Shulman once described his Gan Eden as going again to the Lower East Side and discussing a sugya with Reb Moshe together with his nephew Reb Michel Feinstein, and listening as Reb Michel would interject his uncle’s hasbarah to explain a nuance differently.)

His other seforim include Shomer Hapesach, Shomer Mitzvah, Sukas Shalem, Meirish Babirah, and Kanfei Hanesher.

Rav Ruderman wrote in his haskamah to the sefer Be’er Sarim “You are the first American-born scholar to publish a sefer of such magnitude.” The dreams of the European roshei yeshivah to build Torah in America was realized through people like Rav Shulman, who demonstrated that it was, indeed, possible to develop talmidei chachamim who could hold their own among their European-trained peers.

Rav Shulman had a good role model. He would tell over how the day of his parents wedding was the same day as the shloshim for Reb Chaim Brisker ztz”l. Before walking down to the chuppah, Rav Shulman’s father, Reb Pinchas Eliyahu, attended the hespedim for Reb Chaim in Newark. Only after paying these final respects to the gadol hador did he go on to build his own family.

Although he entered the rabbinate at a young age, he left after a few years and became a stock broker. I once asked him how he was able to keep up with his learning once he started working. “What do you mean?” he asked. “I had much more time than when I was a community rabbi. I no longer had to deal with a kehillah and the sh’eilos that came up and all the other duties that I previously had to attend do. I was free to learn.”

A few years ago, I gave regards from Rav Shulman to his old friend Rabbi Emanuel Feldman ybdlch”t. When I mentioned Rav Shulman’s name, he smiled and recalled that years ago he went to visit his friend Reb Shmerel at his office in the city. He walked in and saw his desk littered with open seforim. “I don’t understand, when do you work?” he asked him.

For over six decades Rav Shulman lived in Kew Gardens Hills, Queens, where he was a fixture in the local batei medrash, learning, saying shiurim, and glossing every sefer that passed through his hands with his marginalia.

While he served in no formal capacity, he was frequently consulted by the local rabbanim on complex halachic issues, and was a go-to person to fill in for a maggid shiur. He would often sit on the beis din of the Igud Harabonim, an organization with which he was involved for decades. When a local shul was between rabbis for about a year, Rav Shulman was the natural choice to fill in.

Rav Peretz Steinberg, who served for 56 years as the rav of Young Israel of Queens Valley, once related that someone approached Rav Moshe Feinstein asking him if he thought becoming a stock broker was an honest profession. “If that’s what Reb Shmerel is doing, then it must be,” was Reb Moshe’s response.

(In the second volume of Igros Moshe, a dozen teshuvos at the beginning of the sefer are addressed to Rav Shulman, in response his many he’aros on the first volume which had been printed just a few months prior.)

Rav Shulman spoke fondly of his friend, the renowned gaon Rav Chaim Zimmerman. Rav Chaim had formerly been a rosh yeshivah in Skokie, and after he left, he moved to New York and dabbled in stocks. “He was aza an illui that he came up with these great chaps in the markets. We either won big or lost big,” he said, “but always with a gutte chap.”

Legend has it that Rav Shach, whom Rav Shulman would visit on his trips to Eretz Yisrael, once commented to Rav Ruderman, “If these are the type of baalei batim you produce, I want to see the roshei yeshivah you produce.”

Many of the great early American rabbanim, although lesser-known, were all a part of his world. He would talk about Rav Shlomo Schuster, Rav Yehoshua Klavan, Rav Naftali Riff, Rav Yaakov Safsel (the Vishker Illui), Rav Chaim Heller, Rav Moshe Don Sheinkopf, Rav Shlomo Schneider, Rav Wolf Leiter, and so many others, speaking of their gaonus in general, or of a particular kushya or encounter that he remembered from them.

His knowledge of the history of any given gadol or sefer was remarkable. When asked about a sefer, he would often give the details of the mechaber’s life along with stories and vertel that they had said. Oftentimes, he heard these stories directly from people who knew them. High on his list was always the Ohr Sameach, written by Rav Meir Simcha of Dvinsk, whose seforim, he would say in the name of Rav Ruderman, must be learned unlike other Acharonim, but as a limud in itself.

Not a single page in Shas slipped through his remarkable mind, not a Shach or a Taz in Shulchan Aruch, not to mention every single Rashi on Chumash which he could pull up by heart.

In recent years, he relocated to Lakewood, where he delivered a weekly Chumash shiur in the beis medrash of the Lakewood Courtyard. The shiur was attended by a gamut of people, ranging from young bochurim to some of the city’s great talmidei chachamim. Many would pipe up with questions, thinking they could catch the elderly man on a particular cheshbon, but it never happened. Rav Shulman fiercely defended his chiddushim as well as the insights he quoted, backed by over eight decades of immersion in Torah.

He was extremely hard to impress. If he didn’t like the vort you told him, he would say so. If it was good, he had heard it already. (There was a man visiting him once telling him vort after vort trying to receive his approval. I was with Rav Shulman at the time, and he turned to me hopelessly and said, “Everything this guy is telling me I heard 70 years ago.”)

I remember one Friday morning when I called him to ask if he was available to learn. “Yes,” he said, “but come quick.” I rushed over, but by the time I got there he had dozed off on his bed. After a few moments he heard me knock something over (I think it was deliberate), and like lightning, leaped out of his bed like I’ve rarely seen from someone 70 years his junior, and said “kumt, lomir lernen,” and in no time he was at his table ready and waiting for me to start reading.

To gain an appreciation of the legendary hasmadah of his youth, he would berate the bochurim who came to visit him for not making good enough usage of their time and not covering enough blatt. He would describe his own bein hazmanim as a bochur as an opportunity to finish masechtos that they didn’t learn in yeshivah. One summer he sat down to learn Zevachim, and the next summer, Menachos. He had the shul to himself in Washington, D.C., where they lived, where he would sit long summer days absorbed in his learning.

Renowned posek Rav Nota Greenblatt, a friend of Rav Shulman for many decades, once commented that “already back in the ‘40s Reb Shmerel was a shem davar.”

When he was a bochur learning in Lakewood, he’d write letters to his parents updating them as to how he was doing. Although the letters were lengthy, the personal parts were quite brief. “It is peaceful here,” he once wrote. “Everything is like last years.” And then, for the next three pages, he wrote over a shiur that he heard the day before from Rav Aharon and signed off. What more did his parents need in order to know that he was basking in the presence of one of the great roshei yeshivah of the day?

The loss of such a man cannot be understated. Ner Israel rosh yeshivah Rav Aharon Feldman said at the levayah that when Reb Shmerel would come back to the yeshivah in the ‘50s to visit, they would do the “pin test” on him all over Shas, and he never failed.

“He was the last Yid in America who knew everything,” said Rav Yankel Drillman upon leaving the levayah.

I saw him zocheh to the brachah of “od yenuvun b’seivah — they will yet grow in old age.” Up until a few months ago, he was still producing chiddushei Torah, a regular contributor to the HaMaor Torah journal.

With Rav Shulman’s passing, the Jewish world has lost not only a great man, a talmid chacham the likes of which almost do not exist anymore, but also lost nearly all access to a generation that is no longer. His great rebbeim, his contemporaries, and his legendary chaburah of friends are long gone.

“And Yosef and his brothers and the entire generation died, on that day.” With the passing of the last of the shevatim, it was not only the passing of one man, but that of an entire generation. For the last several years, Rav Shulman was the last remnant of the legendary Agudas Harabbonim of the late ‘40s and ‘50s. He lived in a different era, yet for those of us who were in his presence, he carried us back with him.

Special thanks to Rabbi Avi Willner, Rabbi Nechemia Finkel, and Rabbi Shraga Neuberger for their assistance in preparing this piece.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 893)

Oops! We could not locate your form.