Remembering the Chasam Sofer

| July 26, 2022One surveying the Hungarian Orthodox scene on the eve of Kristallnacht would have seen the Chasam Sofer’s legacy everywhere

Title: Remembering the Chasam Sofer

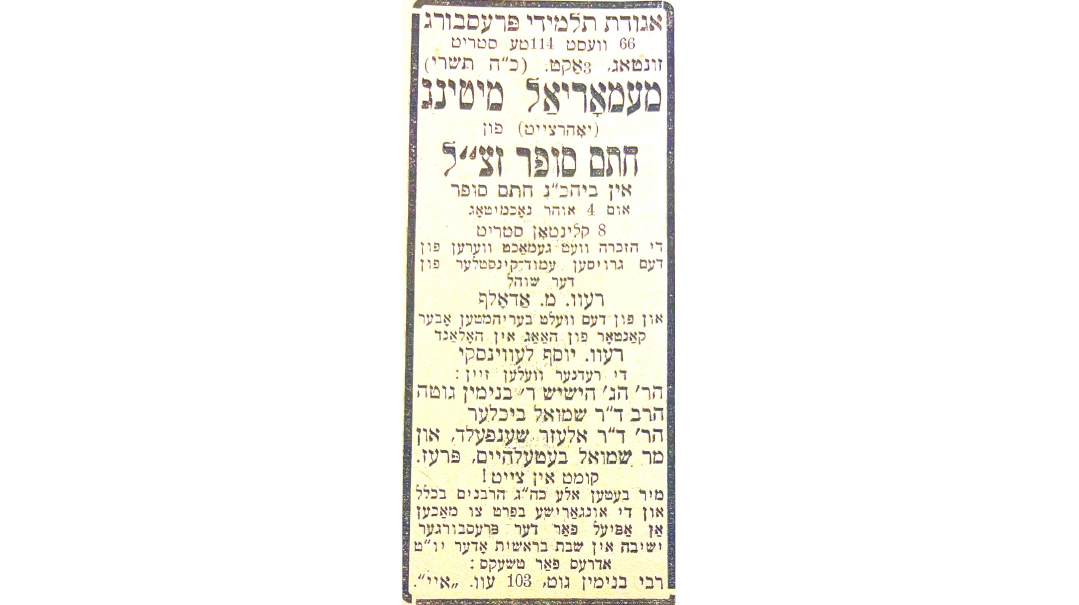

Location: Lower East Side, Manhattan

Document: Dos Yiddishe Licht

Time: 1926

“We, our fathers and teachers, all of us are the product of one man. Moshe has spread forth through the generations! …And anyone who has engaged in [Talmudic] study here in Central Europe, if he is privileged, he will perceive that all streams emanate from the great sea — our mouths should be full of his praises — the author of the Chasam Sofer ztz”l.”

—Reb Shmuel Vizenberg, Kosice, Slovakia, 1938

One surveying the Hungarian Orthodox scene on the eve of Kristallnacht would have seen the Chasam Sofer’s legacy everywhere. Rabbis, yeshivos, communal norms, psak halachah, and the very survival of traditional Judaism itself could be attributed to his leadership and vision.

The awe and esteem in which the Jewish communities of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire held Rav Moshe Sofer, the Chasam Sofer (1762–1839), is almost unparalleled in modern Jewish history. Institutions and communities proudly carried his name, and his Torah was studied, his axioms were repeated, and his value systems were inculcated into subsequent generations. The masses of immigrants from those lands who reestablished themselves in the United States at the turn of the 20th century brought that veneration with them.

That veneration would have an ironic impact. In 1853, immigrant German Jews built a Reform synagogue at 8 Clinton Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, called Congregation Rodeph Sholom. It would be decades until the neighborhood hosted Jewish multitudes from Eastern Europe. The Reform congregation later journeyed uptown, eventually settling on the Upper West Side in 1930.

But in 1892, it had been replaced in its building by a merger of two Polish Orthodox congregations, one named for Czestochowa (northwest of Krakow), and the other named Anshei Unterstanestier (Stanivtsi, Ukraine). They in turn merged with Congregation Chasam Sofer, who continues to use the shul until this very day. In the spirit of Jewish unity, throughout its long history, there were minyanim for both the chassidic nusach (Sefard) in a nod to its Polish founders, as well as a nusach Ashkenaz minyan of the Hungarian Chasam Sofer tradition. There was an element of historical irony in an Orthodox congregation, carrying the name of the most vociferous opponent of Reform, using a building vacated by a Reform congregation.

Known as the Clinton Street Shul, Congregation Chasam Sofer became a flagship of sorts for Hungarian Jewish immigrants, and memorial gatherings were held in honor of the Chasam Sofer’s yahrtzeit to solidify that identity. Though the notice in Dos Yiddishe Licht neglects to mention what was on the menu at this event, there were a slew of prominent speakers and a guest chazzan from The Hague, so it would seem to have been an impressive gathering.

The rabbi was the elderly Rav Binyamin Guth, a student of the Ksav Sofer who assumed leadership of the Chasam Sofer kehillah after he settled in the US. He utilized the yahrtzeit gathering to issue a public call, “to all rabbis and especially those hailing from Hungary, to make an appeal on behalf of the Pressburg Yeshivah on either Yom Tov or Shabbos Bereishis. Address for checks: Rav Binyamin Guth, 103 Avenue A.”

New Shitah, Old Approach

Rav Binyamin Guth was born in Satmar and studied under Rav Binyamin Zev Mandelbaum, Rav Dovid Deutsch, and the Ksav Sofer, great leaders of Hungarian Jewry. In the United States he was active on the Agudath Harabonim and in fundraising for RIETS in its early years. He authored the sefer Shitah Mekubetzes Hachadash, which was a scholarly and historical work of great importance.

Early Ungarish

One of the first students of the Chasam Sofer to come to America was Rav Yissachar Dov “Bernard” Illowy (1814–1871). Arriving in 1853, he served as a rabbi in a plethora of cities, most notably New Orleans and Cincinnati. An ally of Rev. Isaac Leeser, he engaged in polemics with early Reform leaders Isaac Mayer Wise and Max Lilienthal. Rabbi Illowy was often maligned by his opponents over his steadfast adherence to halachah, most notably his ban on the Muscovy duck, which he enacted after correspondence with some of the European Torah giants of the day. (We will expound upon Rabbi Illowy in a future column).

To join the kivrei tzaddikim Mt. Judah cemetery tour with Yehuda Geberer on Friday, July 29, 9:30 a.m., register at: yehudageberer.com.

Thank you to Rabbi Sruly Bornstein as well as the myriad of descendants of the Chasam Sofer who contributed to this column.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 921)

Oops! We could not locate your form.