Regards from Heaven

| April 29, 2020Sgt. Yosef Cohen Hy”d paid the ultimate sacrifice in defense of Am Yisrael, but sent a message of hope from Above to his grieving family

It was last year in Teves, the morning of my brother’s chasunah. My mother was in a taxi in Jerusalem when she heard over the radio the word pigu’a, followed by two victims’ names. This time it was so close — she usually heard about these tragedies in faraway England. She was barely over the shock when the cab pulled up to her destination. As she entered the building where she was staying, she heard wrenching wails in the hallway. A woman was coming up the stairs followed by her husband, weeping so bitterly she looked like she would dissolve in her tears. Her husband led her into an apartment and the sobbing intensified. The woman’s pain was obviously coming from the depths of a broken heart, and my mother, never one to pass an opportunity to ease someone’s pain, felt she had to offer her help — or at least use her power as a baalas simchah to give this poor woman a brachah. Just then, the husband, a distinguished-looking man with long white beard and peyos, came out again. My mother asked him if there was any way she could help.

“Our son was just killed in a pigu’a,” he said, in near-perfect English.

Struggling to hide her emotions, she remembered the radio announcement. “Yossi Cohen?” she whispered.

“Yes,” he answered heavily.

My mother was speechless. All day, she couldn’t get the pained image of the broken woman out of her mind. When she walked to the chuppah that afternoon, she found herself davening not just for her own son but for the mother who had just lost hers. During sheva brachos week, there were placards of the shivah all over. It turns out that Yossi Cohen was the son of prominent parents, well known in Jerusalem’s chareidi community, and especially in the Breslov kehillos of Eretz Yisrael. The room was packed, but Yossi’s mother, Odel Cohen-Merav, a popular lecturer to whom hundreds of women flocked, looked at my mother standing in the doorway questioningly, recognizing her vaguely. “You don’t know me,” my mother told her, “but Yidden everywhere feel your pain. I took my son to his chuppah the same time as you took yours to his levayah, but I took him under the chuppah with me too.”

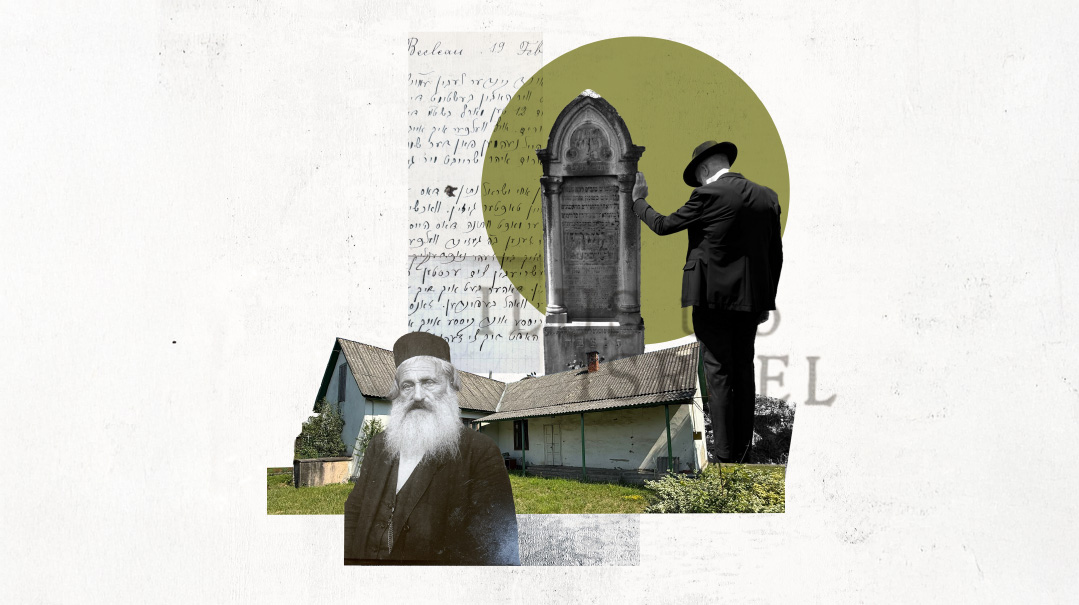

“Nichamtani, nichamtani,” she responded effusively, coming over to show my mother a photo of her sweet son, 19-year-old Yossi Hashem yikom damo, murdered by terrorist fire outside the Givat Assaf junction near Beit El, together with his friend Yuval Mor-Yosef. Both young men were part of the Netzach Yehuda (“Nachal Chareidi”) brigade. She also told her briefly about her and her husband Rav Eliyahu Merav’s own riveting life stories, which merged in their second marriage a mere five years ago.

It is a story of twists and turns, of heartbreak and personal redemption. Now, a year after their son’s murder, as the searing intensity of the pain has morphed into more of a constant, unrelenting ache, Rav Eliyahu Merav — venerated Breslov mashpia and the former mayor of Emanuel — agreed to pull back the curtain and share a bit about his own personal trajectory.

Eliyahu Merav was born in 1950 in Alexandria, Egypt, where his father had a successful textile business. They lived a secular life with minimal tradition, but after the 1952 Egyptian revolution, the family decided to flee to safer shores. They got to Israel via North Africa and Marseilles in 1954, joining two of their children who had already made aliyah and had settled in the Hashomer Hatzair kibbutz of Bet Alfa. They had become Israeli, but Judaism didn’t much figure into their lives on the kibbutz. Eliyahu didn’t even celebrate his bar mitzvah.

When draft time came around, Eliyahu joined the Air Force where he initially trained as a fighter pilot and then switched to the engineering corps, where he eventually rose to the rank of captain during the Yom Kippur War. After the army, a strapping six foot two, Merav decided to join El Al’s security staff, to travel the world and taste the “good life” — what he now refers to in chassidic terminology as “a descent for the purpose of ascent.” Actually, he admits, the spark of spirituality was ignited earlier, during the Yom Kippur War, when the country, facing vulnerability after riding high on previous military victories, was thrown into a whirlpool of introspection. At one point during the war, while riding with comrades through the Sinai Desert, the driver had a serious accident, leaving Eliyahu injured and hospitalized.

Eliyahu was lying in hospital, his mind in a whir of the past few weeks. After witnessing the powerlessness of Israel and how it dodged complete collapse by a hair’s breadth, he was hit by the idea that perhaps Israeli victory and success wasn’t kochi ve’otzem yadi after all, but rather, something orchestrated from Above. His first wisp of inspiration was the South African Jewish doctor who attended to him in the hospital. He talked to Eliyahu about the tachlis of life, propelling Eliyahu’s own inner turmoil and instigating him to find out more.

Eliyahu went on with his life, but the niggling feeling wouldn’t go away. Then he met an old friend, Yehuda Amit, who had become a baal teshuvah and was learning in Yeshivat Hanegev in Netivot (and who has subsequently been a rosh yeshivah in Kiryat Malachi for decades) and talked to his soul about Judaism and Divine Providence. “As Chazal say, a person can do teshuvah in one hour,” Rav Merav says. “I couldn’t just let it go. I was desperate to take a peek before going back to my old ways. And when I told my friend Chana, an El Al airline flight attendant, that I wanted to check it out, she was so relieved, saying she had also secretly wanted to look into Yiddishkeit but had been afraid I would drop her.”

Eliyahu decided to join his friend at Yeshivat Hanegev, and was so taken that he couldn’t leave. With a quaking heart, he went back to Chana: “I’ve discovered the truth. You can either join me and we can get married or you can leave me. Don’t worry, I’ll understand whatever you decide.”

Chana, for her part was ecstatic. She’d also been brought up in a home devoid of Jewish tradition, to the point that when she discovered that she was a descendant of the Baal Shem Tov and shared the exciting revelation with her father, he shrugged apathetically, “I knew that, what’s the big deal?”

Eliyahu and Chana got married with the blessings of the Steipler Gaon and Rav Chaim Greineman, settling in Netivot where Eliyahu spent his every waking moment in yeshivah, making up for lost time.

One day, Rav Eliyahu Alfasi, shamash of the legendary Baba Sali who lived in Netivot, came into the yeshivah and announced that he was looking for someone with a driver’s license. Reb Eliyahu had one, and was told that the Baba Sali had been gifted a Peugeot 405, and from time to time, he would need to be driven places. Did Eliyahu want the honor?

“Not really. Once I discovered this new world of Torah, nothing could tear me away,” Rav Merav remembers. “I was so addicted to the Gemara, I basically came home to my wife Chana and our little baby Elisheva for Shabbos. Chana was like Rabi Akiva’s wife. She went from the life of a globe-trotting flight attendant to the wife of a full-time avreich. I really just wanted to sit and learn.”

But his rosh yeshivah explained what a rare zechus it was. And so, for the next year, Rav Merav merited to drive the tzaddik once or twice a week. “I saw such open miracles with him. You may have read them in books but they actually happened to me.”

One day, for example, the Baba Sali wanted to go to Meron. But as Reb Eliyahu got into the car with the Baba Sali and Rav Alfasi, he noticed that the fuel gauge showed an empty tank. He told Rav Alfasi they would need to fill up before heading out — it was 1975, and gas stations between Netivot and Meron were few and far between. The Baba Sali, however, said no, there was no need, even though it was a 250-kilometer journey each way. Reb Eliyahu had no idea how he would make it, but with the tzaddik’s assurance, off he went, on an empty tank. Some 20 kilometers later, they passed another gas station, but again, the Baba Sali said that he didn’t need to stop. The needle was scratching empty, and Reb Eliyahu was envisioning the tzaddik being stranded on the highway. It seemed inevitable.

Miraculously, he ended up driving to Meron and all the way back to Netivot — 500 kilometers in total — without putting a drop of fuel into the bone-dry tank.

Rav Merav recounts another miracle, this one more widely known. The Baba Sali was famed for his Sephardic-style farbrengens marked by song, dance, Torah and, of course, arak — a strong alcoholic spirit. One patron had bought the Baba Sali an apartment in Jerusalem’s Unsdorf neighborhood, where the tzaddik would make monthly seudos. Reb Eliyahu was there once participating in a yahrtzeit seudah. There were many people in attendance, and the Baba Sali picked up a standard 750-milliliter-bottle of arak, wrapped it in a towel, and started to fill the waiting 200-milliliter glasses. “He poured one glass, two, four, I think at least six glasses to capacity,” Rav Merav remembers. “We all sat there with our jaws open, glued to what was happening, when one person simply could not contain his wonder and broke the silence, exclaiming something like ‘Wow, how can it be?’ ”

The Baba Sali put his bottle down and gave the person a withering gaze that seemed to say something like, “What a pity he disturbed the miracle, as it would have gone on.”

Reb Eliyahu was not a drinker and, as the tzaddik’s driver, certainly didn’t want to get inebriated, but the Baba Sali always insisted that his guests drank whatever amount he gave them — and he would fill Reb Eliyahu two or three cups. Amazingly, the arak didn’t affect Reb Eliyahu’s sense of judgment or reactions at all, and he says it tasted like crystal-clear water.

“He spoke very little, and the little he did speak was usually in Arabic with Rav Alfasi,” Rav Merav says. “But it was frightening how he could literally read my mind. Whatever I’d be thinking about, he would comment on, so I always took special care on my long drives with him to think only divrei Torah.”

Reb Eliyahu was once thinking of the pasuk in Shir Hashirim, “Rosho kesem paz,” where a kallah (Klal Yisrael) describes the head of her chassan (Hashem) like gold. Suddenly the Baba Sali spoke up: “Ketem is roshei teivot kehunah, Torah, malchut,” the tzaddik said, reminding his driver that a person’s tachlis is to stay immersed in Torah.

“For me, that was my chizuk for life,” he says.

Reb Eliyahu could not have been more grateful for his stint serving the Baba Sali, yet conversely, the Baba Sali showed him tremendous hakaras hatov. When Reb Eliyahu and Chana moved to Jerusalem after five years in Netivot, the tzaddik gave them his kedushah-infused apartment there rent free for a full year.

In Jerusalem, Reb Eliyahu reattached to his heavily kabbalistic Sephardic heritage and moved to Yeshivat Ahavat Shalom under Rav Yaakov Hillel, where he earned semichah. After seven years of being a staunch Litvak, he was exposed to Reb Nachman of Breslov’s teachings and he became hooked, combining the two paths to devote himself to a life immersed in Torah and chassidus.

In the early 1980s, the Meravs moved to the fledgling town of Emanuel in the Shomron, which had a Breslover enclave. But the town, created with such infrastructure promise, had suffered a huge setback when the city’s developers absconded with millions, fled the country, and left hundred of families in the lurch, many of them holding onto near-valueless, semi-built homes. The Interior and Housing Ministries contributed massive assistance in the end, in no small measure due to the administrative talents of Rav Eliyahu Merav, who in 1985 became Emanuel’s first mayor — a position he held for the next five years. Pulled off the benches of the beis medrash — Reb Eliyahu had come to the town as part of the Breslov Kollel — he succeeded in putting a new face on the community, making it again a viable housing option for many families. From 1990 to 1995, Reb Eliyahu served as deputy mayor, but then bowed out of politics and moved back to Jerusalem with Chana and their 11 children, where he became a sought-after lecturer, kiruv personality, and Breslover mashpia.

Eliyahu and Chana enjoyed nearly 40 years of marriage, meriting to see all of their children married with families of their own. The first horrific tragedy in their life was the terrorist murder in December 2009 of their oldest son-in-law, Rav Meir Avshalom Chai, killed in a drive-by shooting near his home in Shavei Shomron as ten bullets hit him in the head. (His wife Elisheva, mother of their seven children, has since remarried.)

But then, seven years ago, tragedy struck again — on the very yahrtzeit of their late son-in-law. Chana, Reb Eliyahu’s devoted rebbetzin, who had spurred him on and encouraged his journey to Torah, lost her battle with cancer.

After the shivah, Rav Merav, a 63-year-old empty nester, was left utterly alone, spending his long days in Kollel — the one thing that still brought him solace and joy.

Just one month later, on what would have been their 40th anniversary, a friend called to suggest a shidduch: Odel Cohen, an almanah — and mother of 11.

Eliyahu had no initial interest in remarriage, but astonishingly, it was a match made in heaven. That’s because Odel Cohen needed no introduction. It was thanks to Rav Merav that she and her late husband, Dr. Eitan Cohen a’’h, were frum.

After Eliyahu and Chana Merav’s leap of faith, other seekers were sent their way. The Meravs became strong role models and mashpi’im. One day back then, a friend approached Reb Eliyahu, telling him he’d met with Dr. Eitan Cohen, a dentist with a celebrity clinic on Tel Aviv’s Dizengoff who lived with his wife, a high-end fashion model — then called Anat) — in the affluent beachfront town of Herzliya Pituach. Would Reb Eliyahu give shiurim in the dentist’s house?

And so, over three decades ago, the future couple’s life first intersected.

The Cohens became frum, and Reb Eliyahu and Dr. Eitan became close friends (although in all their years of friendship, he’d never actually met Eitan’s wife, who would one day become his own). “I loved him,” says Rav Merav. “He was a tzaddik. After becoming frum, he and Odel moved to Bnei Brak and he continued to work as a dentist. Chana and I and all our children were his patients. And he merited to serve all the gedolim in Bnei Brak, including Rav Steinman ztz”l, and Rav Kanievsky and his Rebbetzin Batsheva a”h. He was so sincere, that at one point he told Rav Chaim he didn’t want to treat women anymore. Rav Chaim said ‘Bshum oifen, a dentist like you has to treat everyone,’ and he sent him his chashuve daughter as a patient too.”

Reb Eliyahu met Odel the same night she was suggested, marking his 40th anniversary in a bittersweet way. “It was only one month since Chana’s passing. It was very hard, but my first impression of Odel was ‘cut, copy, paste’ of Chana so I was relieved. And people tell me that I’m very similar to Eitan.” Ten days later, they were married.

Reb Eliyahu and Odel’s lives seemed to follow parallels. Baalei teshuvah, 11 children, and Eitan was niftar a year earlier, also to cancer.

How did the 22 children blend? Rav Merav says his children, all married and settled with their own large families, were very supportive of his remarriage. Odel’s situation was a little more complex. She still had seven children at home and the last few years hadn’t been easy for her family. Before Dr. Eitan became ill, their apartment went up in flames, and then one son tragically passed away. And if 54-year-old Odel hadn’t suffered enough, her two oldest sons had recently abandoned Yiddishkeit. The third, who attended a special yeshivah for at-risk teens, was lured out of there by his two older brothers. Living at home was 15-year-old Yossi, who had tread rough waters in the last year, and three younger children.

Nonetheless, Rav Merav, with his long white beard and the over-60 bus pass, relished his new status. “I thank Hashem. My stepchildren made me a young man again. Baruch Hashem, we love each other and they call me Abba. And as for Yossi, so sweet and gentle, we bonded instantly and became close like father and son.”

When Yossi became 18, he told his parents that he didn’t think he was cut out for yeshivah life, and that he wanted to join Nachal Chareidi. Rav Merav, with wisdom and foresight, knew the army wasn’t ideal, but also realized that Yossi could easily follow the path of his three brothers. Odel was devastated at first, but Reb Eliyahu was her rock throughout. And so, Yossi joined the Netzach Yehuda brigade, knowing he had his parents’ love and support behind him, and making sure to come home when he had an off weekend. During his last visit home, he told his mother, “Ima, I want you know that if you think, chalilah, I have become less erlich in the army, you should know that not only am I still strong in my Yiddishkeit, I’m even stronger than I was before.”

Every Shabbos, the family would go around the table and express their thanks to the Ribbono shel Olam for something of the past week, whether it be a good test score or having found a lost item. The last Shabbos Yossi was with them, when it was his turn, he said, “I want to thank Hashem that I have the zechut of defending Am Yisrael with my body.”

Rav Merav and his wife stole a glance at each other. A few days later they understood his cryptic words.

Rav Merav was learning peacefully at home the following Thursday when a trio of army officers interrupted him with a knock on the door. In Israel, every parent instinctively knows what that means. “This morning there was a terrorist attack,” they said. “Yossi was killed.”

“I emitted such a cry it’s good my wife wasn’t home,” Rav Merav says. “But they have instructions to personally break the news to the parents, so they told me to call her home. I said no way. I couldn’t let them crush her like I’d been crushed. She had already lost so much. I said I would do the job.”

He called Odel on her phone. Of all places, she was in a menswear store happily buying a suit for their third son Natan who, to their great joy, was finally starting to make a religious comeback and wanted a respectable suit in order to rejoin yeshivah. It was a huge moment for her, and Reb Eliyahu couldn’t break her heart just yet. He told her to come home, he wanted to talk to her about something important. But somehow a wife knows.

“What is it?” she begged, “Please, tell me.”

Eliyahu insisted it was nothing, but still, she should come home. By the time she did, she saw an army vehicle outside their building. And she knew.

“I was waiting in the lobby downstairs,” Reb Eliyahu remembers, “in order to catch her before the army did. I told her, ‘My dear wife, my rabbanit, please remember, Hashem is merciful, Hashem loves us, ein od Milvado.’ She started screaming, ‘What, what!?’ But I didn’t say more. I simply couldn’t. When she saw the officers, she let out a chilling cry — “Yoseeeeeeeeef!”

The shivah was a hectic week of army officers, politicians, and the media coming to pay their respects and get interviews. Rav Merav, no stranger to the media and comfortable and poised before the cameras, sat shivah even though he was a stepfather.

“Yosef, my dear Yosef, he was so precious to me, mamash like a son. He was so good, so talented. He was a pure neshamah, a devoted child with a golden heart. And he went to Beis Din shel Maalah pure. Before 20, there is no din.

“Thousands came to be menachem us,” Rav Merav continues, “but I got special chizuk from Rav Aryeh Stern [chief rabbi of Jerusalem], who told me that he once mentioned to Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach that he wanted to go to Meron to daven for a particular inyan, and Rav Shlomo Zalman told him he didn’t have to go so far, that he could go to the military cemetery because of the many killed al kiddush Hashem who are buried there. I saw it myself with Yossi. Over the past year people have told me they davened at his grave on Har Hazeisim and they were helped.”

At the shivah, people shared things about Yossi that his parents never even knew. How during the gruelling ground training that pushed the soldiers beyond their limits, there was always a smile on Yosssi’s face. They also heard how, when the soldiers were taken to hospitals and institutions to visit severely disabled and vegetative patients, many soldiers could not handle it, not Yossi. He would hug and kiss the children and dance with them, as unappealing as they may have looked on the outside, and he would dole out candies that he had purchased from his meager army stipend.

“A few weeks ago,” Rav Merav shares, “a friend of mine came back from Uman with regards from a young man who had been in the army with Yossi. The night before he was killed, Yossi pushed this army buddy to agree to go to Uman within the year in order to awaken the bochur’s self-proclaimed sleeping neshamah. And just after Yossi’s yahrtzeit, this friend remembered Yossi’s last request and made good on it.”

Rav Merav was invited to address the crowd in the following annual Memorial Day ceremony for slain soldiers, in the presence of the prime minister and the president. Undaunted by the mixed audience, Rav Merav spoke without hesitation about how the existence of the Jews in Eretz Yisrael is held up by those who sit and learn. That said, he beseeched Jews everywhere to remember that we are one nation. “I served in the IDF and became religious after the Yom Kippur War,” he declared to the eclectic mix of Breslov chassidim, knitted-kippah wearers, secular Jews and national media. “I am an Israeli, I am the product of a crisis in secular Israeli society. I understand that everyone has to live by his faith and values, but mutual respect must be preserved.”

Rav Merav believes it’s time for all of us to make an internal switch. “Hitler yemach shemo didn’t distinguish between the religious and irreligious, because we are all the same Jewish People,” he explains. “I can rebuke you but I have to respect you. Don’t put anyone down, even if you think you keep more Torah and halachah than they do, because they might not have been given the chance to learn, yet tomorrow they can be even better than you. Look at my first wife, Chana, she was a stewardess, she knew nothing when she was growing up, and then she became such an unbelievable tzadeikes — everyone knew Chana Merav. The same with my second wife Odel – today she’s looked up to by hundreds of women as a mashpia, and in her previous life she was a fashion model. Of course we can maintain boundaries but we have to change our inner attitude.”

A few weeks after Yossi’s passing, Odel woke up crying. “Yossi came to me in a dream,” she told her husband, shaking. “He was in a white shirt and he was glowing. I asked him what he was doing here. He said ‘What do you mean, I’m always here.’ I said, ‘But Yossi, we buried you.’ He answered back, ‘What’s your question? You don’t know that there’s no death for a Jewish neshamah? I just changed my clothing but I’m here with you all the time.’ I asked him, ‘Tell me something so I should know it’s not my imagination that you’re here with me,’ and he said, ‘Ima, within this year, all three of my brothers, Daniel, Nachman and Natan will be shomrei Torah u’mitzvot again and they will all be engaged!’”

A year after that dream, Rav Merav reports with uncontained glee, “All three of our sons returned to the path of Torah, and they all got engaged within the year! We’ve been busy making weddings. If you would know how far the boys had gone, you wouldn’t have believed it possible. My wife tried every segulah under the sun. Nothing moved until Yossi went to Shamayim and managed to shake the Heavens on their behalf.”

For Eliyahu and Odel Merav, Yossi’s short-lived legacy is his middos, his mitzvos, and the neshamah always hovering in the background. Could there be any greater comfort?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 808)

Oops! We could not locate your form.