Rebbe of Body and Soul

Rav Eliezer Zev Hager — appointed Rebbe of Vizhnitz-Yerushalayim after his father’s passing — has made it his life’s mission to help Yidden heal

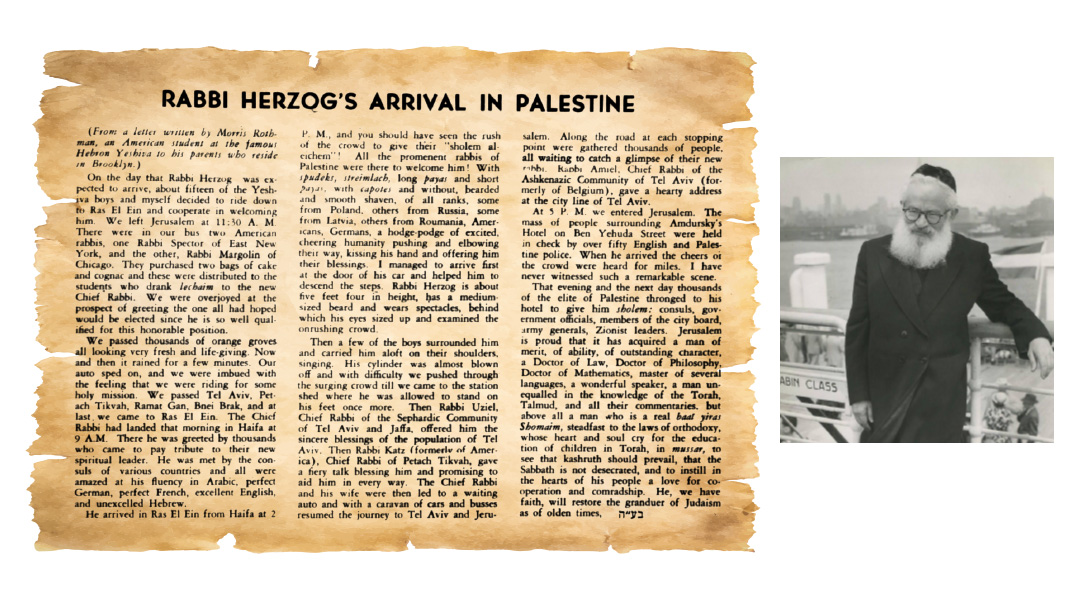

Rebbes don’t usually speak on cell phones, certainly not in public. Yet this Rebbe can often be spotted with the tip of the small flip-phone peering out from under the heavy silver atarah of his tallis, on the phone with doctors, technicians, worried family members and patients, taking calls 24/7 — even on Shabbos — on matters of pikuach nefesh.

Jews across the world know that when a loved one is ill, their address for support, advice, and medical connections is Rav Eliezer Zev Hager, known as the Vizhnitz-Yerushalayim Rebbe (although he is based in New York). And for good reason: Leave a message and he’ll call back. For the past three decades, countless Jews have sought his advice, and rabbanim and rebbes have referred complex medical cases to him, the kind that require rare insight and a heavy sense of responsibility.

Even physicians who’ve never previously met a chassidic grand rabbi are left in awe by this man in distinctive chassidic garb who’s willing to forego a night’s sleep as he waits for the test results of someone he doesn’t even know, or who will run to the hospital during Leil Haseder or before breaking his fast on Yom Kippur to check on one of “his” patients. For the Rebbe, every case becomes personal.

Rabbi, Are You Happy Now?

Rav Eliezer Zev Hager is the fifth son of the Toldos Mordechai (“Rebbe Mottele”) of Vizhnitz-Monsey ztz”l. In 1989 Rebbe Mottele sent his son Rav Eliezer Zev to head the Vizhnitz kehillah in Jerusalem, and although he returned to his father’s court several years later, he became known as the “Yerushalayim Rebbe” after his father’s petirah in 2018. in his tzava’ah, the Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe appointed seven sons and one grandson as rebbes (the Rebbe had eight sons and six daughters, and although one son predeceased him, this son’s son became a rebbe), and they each head various Vizhnitz communities around the world.

When Eliezer Zev was a young boy, his father, the Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe, sent him to Kiryat Vizhnitz in Bnei Brak to learn with his grandfather, the Imrei Chaim, who became his mentor. Eliezer Zev was just a teenager when the Imrei Chaim passed away in 1972, but the memory of his illustrious grandfather still accompanies Rav Eliezer Zev wherever he goes, and many attribute the modesty and joy that he constantly radiates to his zeide’s early influence.

The tireless holy work of assisting the sick and their families and interfacing with medical professionals on their behalf is a calling the Vizhnitz-Yerushalayim Rebbe acquired from his father-in-law, Rebbe Dovid Twerski of Skver-Boro Park ztz”l, who was himself a veritable one-man medical organization, extremely well-connected with top doctors in all areas of expertise.

Nineteen years ago, when the Rebbe of Skver-Boro Park passed away, a non-Jewish surgeon came to pay a nichum aveilim visit, offering his condolences to the family with the following story: “One night,” the doctor recalled, “the rabbi called me to request that I come over immediately to help a Jew who was in great pain. His appointment with a specialist was a way off, but his condition had taken a turn for the worse and it was imperative that he be treated immediately, preferably privately. ‘For you, I’ll do it, rabbi,’ I said to him. ‘But I want to hear that you’re happy.’

“But your father said he wasn’t so happy. ‘I’ll be happy if you reduce the bill for the procedure, even if only by a little,’ he said to me. ‘The patient isn’t wealthy, and he’ll have a hard time meeting the expense.’

“ ’Okay rabbi,’ I said, because I respected him. ‘I’ll make it half the price I usually take. Now are you happy?’

“ ’Still not,’ was the answer. ‘I would be happier if you wouldn’t charge him for the operation at all. He’s a poor man and this situation really hit him out of nowhere.’

“ ’Fine, for you, rabbi’ — I agreed to this too — ‘but only if I’ll hear that you’re finally happy.’

“But the rabbi apparently hadn’t finished his mission yet. ‘I would ask if perhaps you yourself could give him a few hundred dollars to help him live during the period of recovery, before he can return to work. What will the poor man do? How will he eat?’ What could I do? I’d never refused the rabbi, so I treated him for free and gave the patient a respectable sum, so that the rabbi would be happy. And now, when I heard that the rabbi passed away, I felt compelled to come here to express my admiration for that great man, who never saw anything but good in his fellow Jews.”

That story stayed with Rav Eliezer Zev and made a deep impression. As a young man, the Vizhnitz-Yerushalayim Rebbe — who already had many admirers drawn to him for his intense level of avodah and breadth of Torah knowledge — closely observed his father-in-law, learning about this sort of chesed from close-up. But he’d actually accrued an arsenal of medical knowledge before that. When the Rebbe was young, his mother (who was the daughter of Rebbe Yaakov Yosef of Skver) fell severely ill. Eliezer Zev spent seven months with her in the hospital, his young mind absorbing everything — the medical teams, their terminology, the rules, the equipment, the way doctors related to each other. It was as if his brain took in everything and stored it away in anticipation of the time when he’d put his storehouse of knowledge to use in alleviating the suffering of others.

The Vizhnitz-Monsey court has always shunned the press, but in a rare interview in a Yiddish magazine a few years back, Rav Eliezer Zev himself expressed wonder at the fact that doctors treat him with such deference. “It’s all siyata d’Shmaya,” he said, explaining that he’s just the shaliach — a fact that compels him to work even harder, without any kind of personal interest or gain. And like his father-in-law, the Rebbe might even call up a doctor in the middle of the night to request that he take the first flight to another state in order to help a Jew in medical distress. “And,” he’ll tell him, “we can’t compromise on quality, that’s why you’re the man for the job.”

Surprisingly, the doctor will often acquiesce, even if he’s just finished an exhausting workday. The Rebbe’s close people explain that the doctor will do it because he knows the Rebbe himself is also not going to sleep that night. He too will be at the hospital, sitting outside the operating room until the operation is over, praying for good news.

Just a few weeks ago, a Manhattan rav was at Mt. Sinai Medical Center, meeting one of the hospital’s most respected cardiologists. The phone rang and the doctor apologized for taking it. “It’s Rabbi Hager,” he explained, speaking with deference and respect.

Another frum patient recalled sitting with a doctor having a serious conversation. They had just about decided on a course of action — but then the doctor made a suggestion. “Let’s get the rabbi’s blessing, he’s often walking the halls here,” he said, opening the door to his office. Within moments, Rabbi Hager walked by and the doctor ushered him in, sharing the medical plan and waiting for the Rebbe to “sign off” on it and wish the patient well.

“Now we can schedule the surgery,” the doctor said.

We’ll Get through This

Our community has been blessed with many medical advocates with impressive rosters of highly placed professionals. But even those advocates concede that the Rebbe is different. He doesn’t just offer medical advice — he lives the angst of every family, crying together with them, the pain only matched by the happiness when he hears good news, a successful operation or a patient gone home.

The Rebbe attaches great spiritual importance to the mental state of patient and family as well, comforting and encouraging the sick and their families, and instilling them with renewed emunah and hope. These elements, from the Rebbe’s perspective, are no less important than the best physical care.

And indeed, the cornerstone of the Rebbe’s approach to his work is never to give up, even when it seems that a patient’s fate has been sealed. “Once a doctor confided to me about a Jewish patient I was advocating for, that he had only a few months to live — a year tops,” the Rebbe recounted. “Well, that was two decades ago and this Yid has already finished Shas twice. Now, what happened? Did the doctor made a professional mistake? No. It’s just that the doctors don’t take into account the effects of a supportive family, concerned friends, and a burning emunah that gives a person the will to live.”

His confidants explain that while the Rebbe’s focus is on medical protocol, he also knows that panic and hysteria can weaken even a healthy person’s immune system. And so, when people come to him with bleak medical test results, the Rebbe sits down with them, and even before getting into the details, before directing them to the appropriate hospitals and procedures, he encourages them, validates their fear and confusion, and then reassures them that “we’ll get through this.”

The Little Things

When the Rebbe began his medical advocacy career after returning from Jerusalem, he worked the same way he does now — with no office or formal organization. He’s a one-man operation, working the long hospital corridors with only a cell phone.

Years ago, after he returned from Eretz Yisrael, the chassidim learned to appreciate the young, easygoing man who always put others first. He was the sort to leave honors to others, wandering outside the circle of dancers at weddings and events and speaking with those on the periphery.

While others danced with intensity — be it at hakafos, a tish, or a rebbishe wedding, the future Yerushalayim Rebbe was busy making sure that things were in order, helping a lost boy find his father, steadying a teenager at the end of the bleachers, joining an energetic youngster in the search for his fallen yarmulke.

From the Rebbe’s perspective, helping in these little matters is no different from helping a family prepare for a difficult operation on their loved one, and staying up with them through the night to help them weather the anxiety. It’s all gemilus chasadim.

But even a life dedicated to helping Jews medically doesn’t get in the way of life itself.

In Vizhnitz-Monsey, the main currency is Torah, hasmadah, hours by the blatt Gemara. Along with crowning seven sons and one grandson as rebbes, the Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe made conditions: the rebbistive was contingent on learning several hours of Gemara a day without interruption. Otherwise, he said, they would not be able to really help the chassidim.

The Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe used to demand monthly reports from his chassidim on how many hours a day they devoted to Gemara, wherever they were. This was the precondition to being allowed into the Rebbe’s favored circle of intimates, and for his sons, the rules were even more stringent.

When Rav Eliezer Zev (“Velvel,” as he’s affectionately known) speaks longingly of his father, he mentions that the Rebbe’s last public Torah was delivered on Shavuos of 5777, when the Rebbe asked his chassidim to learn a daf of Gemara for his neshamah. Everyone was surprised that that was his devar Torah for Shavuos, but later they understood that it was a sort of last will. He died les than a year later.

Chassidim recount that Rebbe Mottele had a special relationship with his son Rav Eliezer Zev. All the Rebbe’s medical files were given to his son, and he trusted this son to make crucial decisions for him. One time, the Yerushalayim Rebbe recalled, he told his father he couldn’t devote so much time to medical chasadim and also maintain the intense learning seder his father had instituted for him.

“If you can’t keep up with your learning goals, close shop, stop your activities,” the Rebbe told his son.

“Just to reiterate the point,” Rav Eliezer Zev continued, “my father called me back after I’d left the room. The bell rang, a sign that he wanted me to return. I went back and my father mentioned the Chmeilnicki pogroms of 1648, when tens of thousands of Jews were murdered al kiddush hashem. An offer came from Shamayim to the gadol hador, the Sifsei Cohen (the Shach), that if he would agree to be a korban tzibbur, if he agreed to sacrifice himself for his generation, the killing would stop and countless Jews who had been decreed to death would be saved.

“The Sifsei Cohen replied that he didn’t know which was more important, his Torah and the sefer he was writing on the Shulchan Aruch, which would become a legacy for all generations, or sacrificing himself. My father quoted this story and then hinted that the conversation was over. The message was clear: Who told you that your work is more important than your Torah?”

Those familiar with the austerity and intensity of the Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe will acknowledge that the conversation was in character. And those familiar with his son who walks the hospital wards can attest that somehow, he managed to fuse both his father’s missive and his own burning passion to help others.

No Mistakes

Even during the Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe’s lifetime, the spiritual leadership of the chassidus was peacefully divided between his sons. In his will, the Rebbe specified in which kehillah and city each of his sons would fill in for him. And so, in the two years since his father’s petirah, the Yerushalayim Rebbe regularly travels back and forth over the Atlantic, serving as the spiritual guide for the Vizhnitz-Monsey beis medrash on Adoniyahu Street in Jerusalem.

Even as he officially serves as an admor in Jerusalem, he never stands on ceremony, davening as a regular member of the minyan in any city his medical affairs take him. “He accepted the leadership, but he hasn’t given up his shlichus,” say his chassidim.

But once he took on the leadership role as a rebbe, the same chassidim couldn’t help but notice intense moments of kedushah that seemed to overtake his entire being. As a son at his father’s court, he kept his inner fire within. It wouldn’t have been appropriate to raise his voice in song or burst into dance in his father’s presence. Now that he’s a rebbe in his own right, he can give free rein to his overflowing emotions.

During his first Simchas Torah as head of the kehillah, the Rebbe broke from the Vizhnitz tradition of circling the bimah only once per hakafah. He danced with an ecstasy and fervor that ignited the entire crowd, as he gathered the children around him and swept around the bimah again and again in an outpouring of joy and love for the Torah. The Vizhnitz-Monsey chassidim in Jerusalem have since expanded their beis medrash in his honor.

The Rebbe revived an old chassidic folk song that might be interpreted as his personal anthem (to the tune of “L’aasos Nachas Ruach”): “Mir meinien nisht kein kavod, mir meinen nisht kein gelt, mir meinen dem Bashefer, fun di gantze velt (we don’t intend it for honor or money, but only for the Creator of the World).”

These words, say those who know the Rebbe closely, express the essence of his soul. While many public figures need to constantly struggle to get their egos under control, the Rebbe would have a hard time understanding the concept.

In fact, the Rebbe’s self-effacing joy and love of life is something he’s sought to impart to the chassidim from the time he was just a bochur in his father’s court. Back when Reb Velvel was young, his father, Rebbe Mottele, moved the chassidus’s yeshivah out of town, since he didn’t want the bustle of the chassidic court to interfere with the bochurim’s learning.

This was a novelty in those days — the idea that the bochurim, who as the Rebbe’s entourage at the tishen and the Shabbos tefillos lend the chassidic court much of its grandeur and dignity, should be removed from the scene just so that they could better concentrate on their tefillah and avodah.

The location chosen for the yeshivah was the village of Kiamesha Lake, an hour and a half’s drive from Monsey. Every Shabbos a different one of the Rebbe’s sons would be sent to the yeshivah to spend Shabbos with the bochurim, to lead their davening in the poignant Vizhnitz nusach, and to sit down with them to a botteh on Friday night, as a substitute for the Rebbe’s tish.

Until today, the bochurim of those years (most of them are by now heading their own families) remember the excitement when it was Rav Eliezer Zev’s turn to spend Shabbos with them. They knew it would be a Shabbos of joy, especially if he served as the baal tefillah. There would be vigorous dancing, sippurei tzaddikim, and uplifting excitement that wouldn’t leave anyone out in the cold.

Today his derashos haven’t changed much — they’re still replete with divrei Torah and sippurei tzaddikim revolving around the steady theme of emunah.

In a recent derashah, the Rebbe reflected: “My great-grandfather, the Ahavas Yisrael, had a custom of playing chess on the night of nittel, when it’s customary not to learn Torah. The world says that there’s a symbolism in the game. The lowliest pawn, by moving slowly and patiently, one step at a time, can overtake the king.

“But my Zeide would say that there’s a weakness to the game: If you lose your concentration for just a moment and make a mistake, there’s no taking it back. ‘And that,’ the Ahavas Yisrael would say, ‘that’s an idea I can’t accept, that you can’t take back a mistake…’ ”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 813)

Oops! We could not locate your form.