Reading Between the Lions

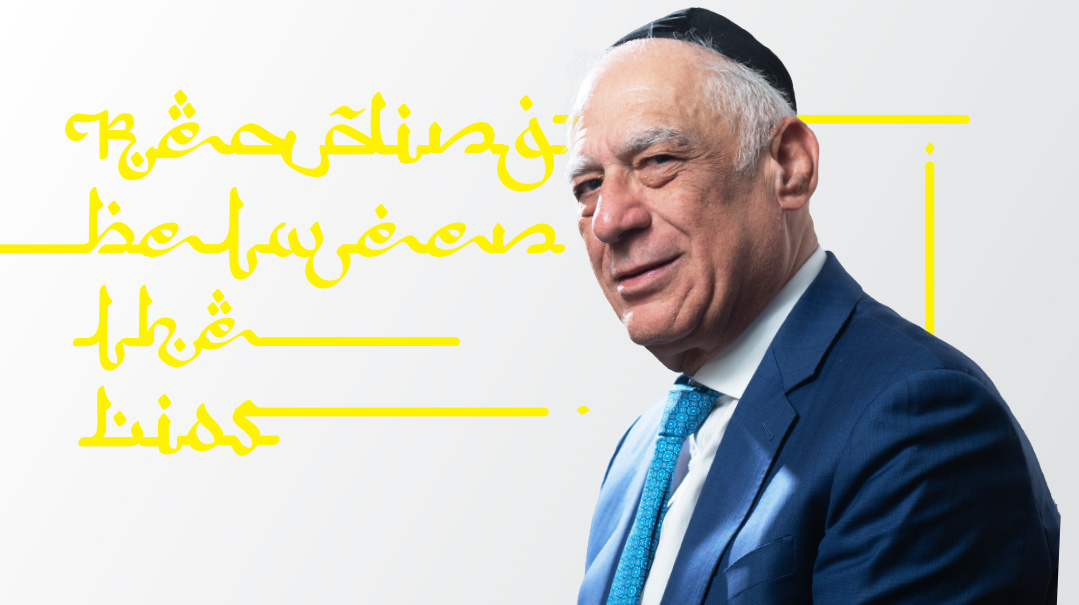

| January 7, 2025Rafi Nakash revisits the paradox of his life in Syria while mourning the future of a nation he once called home

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian

Rafi Nakash was a young Syrian government official who learned how to utilize the system under Hafez-al Assad – until he fled to the US and never looked back. Today, with his company one of the largest shoe importers in the country, he reflects on those times, bearing a grudging respect for Hafez al-Assad and grateful that the Jews left before Bashar, his ill-fated son, came to power – and shares some surprising revelations about the current coup

“Every Jew who lived in Syria needs to say Kaddish for Hafez al-Assad.”

With this bombshell, Phileh (Rafi) Nakash — frum Jew, former Syrian government official, and current member of the Manhattan business elite — blows up some of the common narratives regarding the regimes of the Assad family, and the fortunes of Jews under their rule.

Make no mistake about it: Nakash suffered extensively at the hands of the regime. He witnessed his father’s arrest and torture, dodged institutionalized discrimination and anti-Semitism, and lived under crushing restrictions in the shadow of a fearsome secret police.

“But you could work with Assad,” Nakash explains. “We learned how to play the system — it was manageable.” Without denying the dictator’s evil and cruelty, Nakash still bears a grudging respect for the older Syrian strongman — which cannot be said for his ill-fated son.

Today, watching from a distance as his native country struggles to right itself amid a heaving sea of uncertainty, Nakash is filled with suspicion and doubt. Promises made by new regimes — if experience means anything — are not necessarily promises kept.

To the Drawing Board

Rafael Nakash was born in 1956 in Aleppo, Syria, to Yusef and Alice Nakash. Yusef was a successful textile merchant, while Alice raised the family of three boys and six girls. The family was part of the Halab (Aleppo) Jewish community, which numbered about 1,200 people. The larger Syrian Jewish community of Sham (Damascus) was comprised of about 4,000 people, while a handful of Jews resided in Qamishli, a city near the Turkish border.

The family resided in a comfortable home that had been appropriated by the Syrian government from a Jew who had left the country during the 1948 riots. The local economy at the time was such that they paid just $100 a year in rent for the house. Rafi married Ninette, a childhood friend, and later took over the house, living there with his family until they left the country in 1986.

After attending Aleppo University and earning a degree in engineering, Rafi went to work for the General Organization for Housing (GOH), a Syrian government construction authority. He rose quickly through the company ranks. By the time he was 26, he was chief of four departments, responsible for 735 employees and an office staff of seven secretaries, and was assigned a personal bodyguard.

“I was the only Jew in Syrian history allotted a government car,” Nakash says with a chuckle. His work put him in close contact with senior government ministers. Most importantly, he did not have to work on Shabbos and Yom Tov — a rare luxury in Syria.

In 1986, at the age of 30, he left it all behind, fleeing Syria for a new life in the United States. Starting over as a stockboy in a shoe store, he built himself up again from scratch. He currently lives in Brooklyn and owns Rasolli Shoes, in partnership with his brothers. The company, headquartered in Midtown Manhattan, is one of the largest shoe importers and distributors in the country, with a portfolio of thousands of high-end clients.

How did he do it? The same combination of grit and wit that enabled him to survive the terrorist regimes in Syria was the driver of his current success. As he says simply: “We work hard.”

Aleppo, Syria, 1984

The special assistant to Prime Minister Abdul Rauf al-Kasm stepped out of his shiny government limousine, flanked by assistants, security teams, and other government officials. He had arrived to inspect 30 new apartment complexes, totaling 900 units, built by the GOH.

The assistant prime minister and his team toured the new buildings, studying the construction and design. Soon, he began asking questions and issuing criticism, wanting to know why the buildings weren’t built differently. His displeasure was clear. “Who made the decision to build these buildings in this manner?” he demanded. Other ministers murmured their concurrence with the critique.

One of the company officials guiding the group pointed to a 28-year-old man. “This is the engineer in charge,” he said. All eyes turned to Rafi Nakash. The minister waited for an explanation.

“Honored minster,” Nakash said boldly. “Are you an engineer? No? I’m sorry, but I cannot discuss technical design points with people who do not have a background in engineering.” He turned to the rest of the politicians. “Are any of you engineers? Also not? No engineers in the group?” He crossed his arms confidently. “These decisions were based on engineering. If you have an expert here, I can explain them to him.”

Several days later, Rafi was summoned to the office of his supervisor at GOH, Suhel el-Hassan. “Rafi, what did you say to the deputy prime minister?” the chief asked.

“Before you continue, let me tell you something,” he answered. “I am a Jew. I can never be president. I can never be prime minister. I can’t even be a chief in this country. You have taken away many of my rights. But one thing you can never take away from me is my intelligence.”

Although the minister had been furious at Rafi’s disrespect, Rafi’s supervisor was impressed by his firm response and backed him up. In time, the incident blew over.

During the early years of Rafi’s childhood, Syria smoldered under a series of coups, and governments changed every few years. His first significant memory dates to 1963, when tanks rolled into central Aleppo as the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, led by Amin al-Hafez, seized power.

The new regime imposed a random assortment of purposeless rules designed to hound and terrorize the al-Yahuds — the Jews. These were enforced by the mukhabarat, or Syrian intelligence services — a violent secret police that controlled the streets with a level of ruthlessness that would impress even the Soviet KGB.

Under the new decrees, all Jewish-owned passports were stamped with the word “Musawi” (“from Moses”). Bearers could not travel more than two miles outside of their home city without authorization from the mukhabarat. For every city he wished to visit, a Musawi needed another mukhabarat stamp in his passport. Otherwise, when he showed his documents to any random officer or hotel clerk, he would be reported and quickly disappear into mukhabarat dungeons.

Jews could not buy or sell products, and couldn’t attend university. Needless to say, they were banned from leaving the country. This was officially to prevent them from emigrating to Israel, but Nakash waves away that suggestion. “Stupid rule. They were just looking to bother us.”

When Rafi turned 13, he joined his father’s textile business. This meant that his daily activities — travel and sales — required constant authorizations from the mukhabarat, sometimes four or five per day. Approvals required a lengthy and demeaning application process, and a hefty dose of grease from the pocket.

Into the Lions’ Den

At the end of 1970, Hafez al-Assad, defense minister of the Ba’ath Party, initiated another coup d’état, ousted then-President Nour al-Din al-Atassi from power, and put himself in charge as prime minister; by early 1971, he was elected president, a position he retained until his death. He was a brutal, bloodthirsty totalitarian ruler.

Hafez al-Assad referred to himself as the “Lion of Damascus.” The name “Assad” itself means “lion” in Arabic, linking the family name to the ancient Syrian symbol of the lion, and the Assad regime (which would include his son Bashar after his death) used the lion as a propaganda symbol of strength and authority. And it wasn’t just for show: Putting down a 1980 rebellion, Assad’s forces wiped out 100,000 people in just days. The fourth-largest city in the country was almost completely annihilated.

But Nakash found that life for the Jews improved.

“It’s key to understand that Assad belonged to a religious and cultural minority in Syria,” Nakash explains. About 50 percent of the Syrian population were Sunni Muslims, members of the notorious Muslim Brotherhood. Christian Arabs made up 30 percent, ten percent were Alawite Muslims, and the rest of the country was a mixture of Armenians, Kurds, Shiite Muslims, and a handful of Jews. Assad, an Alawite, saw his power base in this assortment of minorities, and perceived the Muslim Brotherhood as a threat. He therefore rolled back some discriminatory policies of the Ba’ath Party, and made life easier for all minorities — even the Jews.

Some of the restrictions on Jews were eased, albeit incrementally. More importantly, this regime could be reasoned with, and the system could be managed. Although many of the discriminatory laws and policies remained, Jews, including Nakash, learned to make the system work for them.

Often, they were even able to turn the anti-Semitism to their advantage.

Rafi learned which mukhabarat commanders could be cultivated as allies. Years of dealing with the secret police for his travels as a textile salesman allowed Rafi to build strong relationships within the organization, and to develop connections with the mukhabarat chief of Damascus and a number of other ranking officers.

Still, anti-Jewish discrimination from rank-and-file citizens was rampant. Here, too, the mukhabarat — themselves usually from the Alawite minority — were helpful.

“People would start up with me, the Jew,” Rafi relates. “I’d call the mukhabarat captain, and he would haul the offender into his office. He would say, ‘Oh, you don’t like Nakash because he is a Jew. Does that make you a member of the Muslim Brotherhood? Because you know how we deal with them!’

“You have to understand the Arab mindset,” Rafi explains. “If they sense weakness, they will stomp all over you. You need to appear strong — but more than that, the source of your strength must be mysterious to them.”

It took a mukhabarat connection to overcome obstacles for a Jew attending Aleppo University, where Rafi earned a degree in engineering. Upon graduation, government officials wanted to pigeonhole him into a dead-end job on the periphery. But Rafi would have none of it. An intervention on his behalf by the chief of the Damascus mukhabarat office helped him land an internship with the General Organization for Housing (GOH).

At some point in his career, Rafi was assigned to lead a prestigious construction project, building luxury villas for Syrian Army officers. He knew it would not last — inevitably, some jealous underling would complain that a Jew had such an important job, and try to get him removed. Sure enough, his supervisor soon called him in to his office.

“Let me guess,” Rafi preempted him. “I’m being transferred off the project.” The man nodded. “Tell whoever it is,” Rafi threatened, “that he better not sleep in his bed tonight if he understands how things work around here.”

With that, Rafi went to visit a mukhabarat chief. The man made a few phone calls on his behalf. Indeed, the snitch did not feel safe in his bed that night, and the terrified CEO of the organization summoned Rafi to try to mollify him.

Again, with unique ingenuity, Rafi turned the anti-Semitism to his benefit. As a Jew, he couldn’t go back to his old job without raising questions. He couldn’t work on the new job, he argued, because the people who tried to get rid of him the first time would continue to find ways to frame and disqualify the Jew. The only solution that would satisfy the mukhabarat, Rafi said, was for him to be promoted.

And that’s how he was put in charge of his first department.

All this is not to say Assad wasn’t a dictator who reigned with terror or that life was comfortable for Jews. In 1982, a Jewish woman, a classmate of Rafi’s at university, was murdered in cold blood by Alawite police, along with her two children, after complaining that she had been a victim of a crime. He recalls the mukhabarat executing an entire neighborhood of men — including a world-famous academic professor — in search of a criminal.

Life for Jews was dangerous — but again, this helped Rafi. There was no shidduch crisis in Aleppo; everyone in the close-knit community knew each other. Rafi and Ninette grew up together. In fact, Rafi had served as a sort of personal protector for her since they were 12 years old.

“It wasn’t safe for a Jewish girl to move about the streets alone,” Rafi says. “There were five boys and five girls my age. Whenever a girl needed to go somewhere, a boy was assigned to accompany her. As a result, when it came time for marriage, matchmaking was pretty much a done deal.”

Ninette almost didn’t make it to the wedding.

In 1972, a local Arab man knocked on the door of a Syrian Jew named Isaac Kassab. When he unlocked the door, the man pushed his way inside and attacked, murdering Kassab H”yd in cold blood. Under interrogation by local police, he explained his motive: “I just wanted to kill a Jew. I decided to murder the first one I could find.”

“Did you knock on any other doors?” the police asked.

“Yes, I tried Dr. Bakar, I figured he always sees patients and I could get inside. But he wasn’t home.”

Dr. Bakar was Ninette’s father. He had been diagnosed with cataracts, and had corrective surgery days earlier. Through a special act of Hashgachah, he was convalescing in a medical facility when the murderer knocked at his door. Ninette had answered the knock, but she spoke to him through the glass. When the man asked to see her father, she told him the doctor was away, and he left. His next stop was the home of his victim.

Keeping Torah and mitzvos was a struggle. The day off in Syria was Friday — anyone asking to take off on Shabbos immediately raised suspicion. Even with his power and position, when Rafi took off on Shabbos, he was harassed. “What do you think this is, Israel?” a supervisor asked.

In 1972, a group of Jews, including Rafi’s brother, tried to escape Syria. They hired a team of smugglers to secretly get them to Turkey. Thugs themselves, the smugglers killed some of the group who didn’t move fast enough for their liking. Rafi’s brother survived and made it to Europe.

In retaliation, the mukhabarat arrested the fathers of all the escapees. Yusef Nakash was taken prisoner and hauled off to a dungeon ten stories below ground, where he suffered endless interrogations and torture. Eventually, he was released — but was a shadow of his former self. Several months later, at the age of 52, he died of a heart attack. Alice Nakash remained a widow for the ensuing 40 years, until her passing five years ago.

Restrictions were tightened on the Jewish community after the escape. A special unit of the mukhabarat, called “Falastine,” (Palestine) was set up just to deal with Jews. Anyone with “Musawi” on his passport had to report to the local mukhabarat office every night by eight p.m., to demonstrate that they had not fled. A strict curfew was in place from that time until morning. Every few months, mukhabarat officers would round up the Jews in the city center and count them, a procedure eerily similar to the Nazi aktion, to make sure no one was missing.

Time to Flee

In 1981, thanks to Rafi’s connections, Alice Nakash escaped Syria and moved to the United States. In 1986, Rafi and his wife applied for permission to visit her. It took some time, but with help from people in the right places, he received it. Owing to his prestige, no one considered him a flight risk.

He has never been back.

Upon landing in the US, Rafi and his wife took a taxi to his mother’s home, and arrived without incident. He was shocked.

“No one stopped us and demanded to see identification,” he told Ninette. “Can you imagine traveling for an hour in Syria without being asked for ID?”

At that moment, the couple made a snap decision — to stay in the US, fleeing Syria and the Assad regime forever. This was not as easy as it sounds. Their children, aged five and three, were back home, staying with Rafi’s siblings. They had no job, no income, didn’t speak the language, and had left all their worldly possessions behind. But they did it anyway.

“Thus began the darkest part of my life,” Rafi says. First, he wrote to the mukhabarat, and told them that his wife had taken ill. He sent reports from doctors ordering five years of treatment in US hospitals, and asked for permission for his children to join them. The secret police were furious, and not inclined to grant the request.

Rafi continued to write letters, pulling every string he could muster. At some point, in desperation, Rafi called the Damascus chief mukhabarat officer. “After all I’ve done for Syria,” he said, “don’t hold my children hostage.” It took 14 months and a hefty sum of money — but eventually, the children arrived, traveling with Rafi’s brother.

The family was together in America. But where would they find work? With nothing but the shirt on his back, the former chief construction executive and engineer took a job as a stock boy in the basement of shoe store, but not for long. Within six months, Rafi and his two brothers opened their own business, eventually growing it into the empire it is today.

Despite all the hardships the community suffered, Rafi gives credit to Hafez al-Assad. “He was by far the smartest president in the world,” he says. Under him, the country turned prosperous. People had late model cars and there were quality products available.

On foreign policy, Assad struck the balance between developing relationships with other powers and ensuring they did not interfere in his affairs. His government cultivated alliances with Russia and Iran, and maintained an understanding with the United States. But Hafez was careful to limit the influence of these countries.

“He never allowed foreign military presence on Syrian soil,” Nakash testifies. “Not a single Russian or Iranian soldier set foot in Syria. He didn’t trust them. Assad met with US President Bill Clinton twice — but always in neutral territory. He would not travel to the US or allow Clinton to visit.”

In 1992, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger brokered a deal with Assad, allowing Jews to leave the country — as long as complete family units did not leave. Over 4,000 Jews left at that time.

“This is why I say Jews should say Kaddish for Hafez,” Rafi explains. “He saved the lives of all of them. If they would have still been there when Bashar took over, not one would have survived.”

Hafez al-Assad died in 2000. Bashar al-Assad, who had returned to Syria just a few years earlier from London, where he had been furthering his ophthalmology studies, took over the country. The new leader and his wife, Alma, initially spoke of reform, modernization, and westernization of the country. Watching from a distance, Rafi Nakash and the circle of expatriate Syrians knew this was a mistake that would lead to a trail of blood. It made Bashar appear weak, forcing him to struggle and compromise to stay alive and in power.

“The Muslim Brotherhood were the majority in the country,” Nakash explains. “Even under Hafez, they were agitating and looking to rebel, but he ruled with strength and they were afraid to organize. Once Bashar showed weakness, it set in place a cycle of events that led to his downfall.”

Bashar’s personality was soft, and his talk of reform infuriated and emboldened the majority Sunni Muslim brotherhood in the country, Rafi explains. He didn’t have the same control his father had. This forced him to become dependent on Russian and Iranian support.

Once you let the bear into the house, it’s very hard to get it out.

Russian military bases were set up in the country, and Iranian arms flowed across the borders. Both countries gained a foothold on Syrian territory, and began to manipulate Bashar. The majority Sunni population grew stronger as well, and the regime tottered.

Struggling to stay in control, Bashar turned to brutality, surpassing even that of his father. Still, the Muslim Brotherhood’s power grew. Thankfully, there were almost no Jews left in Syria by then.

“If Hafez had not let the Jews out in 1992, the Muslim Brotherhood would have killed them all under Bashar al-Assad,” Rafi Nakash says.

Aleppo was pretty much empty of Jews by the time Bashar came to power, and a handful were still in Damascus. They left over the next several years, and still have very painful memories of that time. Mishpacha located a number of them, but they were unwilling to talk about life under Bashar, even anonymously. Their experiences were apparently very difficult, and very different to that of Rafi Nakash. The last few Jews to leave were evacuated by a special operation in 2015, organized by askanim from the Syrian community abroad.

Brutality or Weakness?

In 2011, civil war broke out in the country, following the successful Arab Spring rebellions in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia. It’s widely assumed that the revolt was inspired by people yearning to be free of oppression, but Rafi tells a different story, one of weakness, not brutality.

“It never would have happened under Hafez,” Nakash asserts. “The majority Muslim Brotherhood wanted control for years. Bashar was weak and they made their move.” Still buoyed by Russia and Iran, Assad battled the rebel forces for 14 long years. Millions of Syrians died in the conflict. Eventually, with Russia preoccupied in Ukraine and Iran licking severe wounds inflicted on its regional empire this year by Israel, rebels led by the Islamist militant group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham toppled Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

Nakash and the expatriate community don’t believe the full story of Assad’s downfall has been told.

“It doesn’t make sense,” he says. “How did it fall apart so suddenly, so quickly? They took control of Aleppo with a few motorcycles and trucks, in a day? Impossible. And why did Bashar flee in the middle of the night, without even his closest advisors knowing that he was leaving? How did he abandon all his ministers, all the chiefs and leaders of the mukhabarat, to face the rebels with no organization? No one does that in Syria.”

According to Nakash’s understanding of Syrian government, something more sinister was at play.

“Russian and Iran had a hand in this,” he says. “The big guys must have decided that it was over, that it was in their best interests to pull out Assad and leave the country to the rebels. Turkey was probably involved as well. There’s no other explanation. Syrian politics just doesn’t work this way.”

Nakash also suspects the involvement of US and European interests.

“There’s no question that Assad had backdoor deals with the US and Europe to keep him in power. And how did he stay out of war with Israel for so long? There was a deal between the two countries that will never see the light of day, for fear of the wrath of other Muslim powers.”

Nakash and the Jewish community have very few financial interests in Syria (although they are working hard to preserve the community’s sacred heritage and mekomos kedoshim). But Rafi is in touch with a network of Christian Syrian expatriates who do have interests there, and what they see is concerning.

The new regime that will rule Syria is still under construction, but its leader, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham chief Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, is promising tolerance and civil rights for minorities. Nakash doesn’t trust him or his promises.

“See the signs in his government,” he advises. “Everything points to a takeover by radical Islamist forces. All the ministers appointed to his Syrian Transitional Government are members of the Muslim Brotherhood. There are no minorities — no Kurds, Armenians, Christians, or Alawites. No women. There are signs of intolerance — as soon as they took power, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham fighters burned the central holiday tree erected by the Christians in Damascus.

“Al-Jolani was formerly chieftain of Jabhat al-Nusra, which was affiliated with al-Qaeda. He split from al-Qaeda and created Jabhat Fatah al-Sham, and subsequently merged with other groups to form Hayat Tahrir al Sham. A member of al-Qaeda does not quickly change his stripes.

“Remember,” Nakash warns. “In this environment, the only difference between an ally and a terrorist is whether or not someone screams, ‘All-ahu Akbar!’ ”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1044)

Oops! We could not locate your form.