Ray of Light

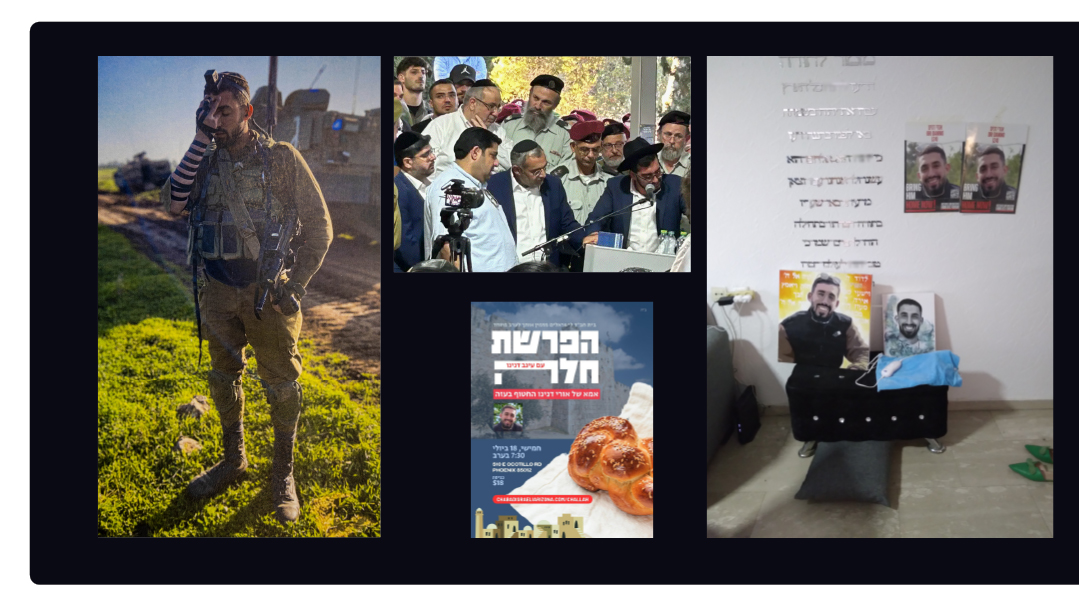

| September 10, 2024The parents of murdered hostage Ori Danino radiate unbroken faith

When their son Ori disappeared into the darkness of the Hamas tunnels, his parents chose to spread a message of light in Israel and abroad.

Last week, after the horrific news of his fate emerged, they spoke of Ori’s path of kindness, and those he’d saved on that dreadful Simchas Torah morning.

In two searing conversations, Elchanan Danino urged greater unity and empathy for the hostages, and Einav spoke of the emunah that she’s shared over the last year. The unity and faith that has accompanied Ori’s ordeal, they say, should be a guiding light as Klal Yisrael navigates the road ahead.

It’s Chol Hamoed Succos, and a shaky cellphone camera records as a chareidi family sings in celebration of a Yom Tov that’s about to turn to grief. Among the white-shirted boys singing joyfully, a tall man dressed in black sports gear doesn’t seem to fit. But as the family sings “Middas Harachamim,” he joins in with fervor. “Ube’ad amcha!” he cries in the video, “ube’ad amcha, ube’ad amcha rachamim sha’ali!”

The clip is a chilling one because of the aftermath. This was the last gathering that soldier-turned-Hamas-captive Ori Danino Hashem yikom damo joined with his family. “Who would have believed that a few days later, Ori would be held by these cursed murderers in captivity?” says his father, Elchanan. “Oy, Tatte, instead of middas harachamim, we had middas hadin.”

The full measure of that judgment landed on the family last week, when they learned — via rumors swirling on the media and chat groups — that their son had been murdered inside a Hamas tunnel.

“Yes, those leaks from irresponsible people reached me as well,” says Elchanan Danino. “And I want to tell those murderers at the keyboard: Know that from the time Shabbat ended, as the dreadful rumors spread, we were murdered, plain and simple.

“From that moment, I tried to contact all the relevant entities in the IDF, but none of them gave me information that bodies had been rescued. Meanwhile, the names continued to be publicized, and my son — oy, my son — he was on the list. They killed us. This is dinei nefashot. We went through this nightmare until four in the morning.”

That was when the official news came.

The officers who knocked on the Daninos’ door in Yerushalayim at 4 a.m. with the horrible news brought to an end 11 months of suffering and hard-fought emunah.

Spiritual connection was something that Ori took from his parents, despite forging his own path away from their way of life. As an officer in an elite IDF unit, he hadn’t been able to daven with a minyan on Yom Kippur. Yet, to immerse himself in the spirit of the day, he would listen to the piyut of “Lecha Keili Teshukati,” by Rav Nissim Gaon, in order to feel Yom Kippur.

And as the family comes to terms with the loss of their eldest, it’s specifically to his own community and side of the political fence that Elchanan Danino speaks.

“Rabbosai, don’t ever lose touch with your children,” he says. “Even if they don’t completely follow your path and even if they don’t always do what we want them to — continue to love them and hug them, despite everything. Because in the long run, it will make a difference, and they’re our children. They don’t have other parents.”

After almost a year over which the issue of the hostages went from being an Israeli consensus to a deeply-politicized struggle between right and left, Elchanan Danino has a strong message for the chareidi community, whose voice has been practically inaudible on this critical issue.

“Unfortunately, there were times that we had this feeling that in the chareidi community, we don’t really feel the pain of the hostage families. It doesn’t have to be that way.”

Living to Give

The Danino family’s ordeal began on Simchas Torah at 2:30 p.m., when officers knocked at their door. “They said to me, ‘You’re chareidi, you’re not watching the news, but you should know that your son was called up at 6:39 this morning to his unit. He said he’d come. His friend showed up, but he did not.’

“Then they said, ‘We know right now that at 9:12, his phone crossed the border.’

“There was no official confirmation yet that he was abducted, but 11 days later, we found out that he’d been kidnapped by a terrorist group in Gaza. Later, it came out that he was being held by Hamas.”

They didn’t know what their oldest son had endured on that dreadful morning, or how many people he had saved with mesirus nefesh. Only later did Ori’s family hear the full story.

“When the terrorists got to Re’im,” Elchanan relates, “Ori and his friend Tomer had already managed to flee the danger zone. They ran through the surrounding fields, each one of them was able to get to his car and escape. On the way, Tomer saw that Ori’s car was behind him. Then he got a message from him, ‘Send me Omer’s number, Maya, Itay, someone.’

“Tomer said to him, ‘Danino, we’re not going back there. They’ll shoot us.’

“Ori answered him, ‘You run, I’m making a U-turn, I’m going to get them.’

“Ori merited to save Maya and Itay Regev, who were released in the hostage deal, and he also took Omer Shem Tov with him. Unfortunately, Omer is still a hostage in Gaza.

“And the truth? This story doesn’t really surprise us. We knew that this was Ori. It was clear that this was what he would do if he got into such a situation.”

All of those who come to be menachem avel have a similar story: Everyone describes Ori as a baal chesed. That’s how they knew him.

“A few months ago,” his father says, “a friend of Ori’s asked me to say one of the brachot under his chuppah. I didn’t understand why he was even inviting me, because I didn’t know him at all. But then, that friend shared with me something I hadn’t known.

“He told me he wasn’t born in Israel. He had come from America. He was a lone soldier without family in Israel, hardly knew anyone. He had slept in the same room as Ori for two years.

“He told me that every time Ori came back from a Shabbat at home, he would bring him leftover food and his clean laundry. Ori would hide this lone soldier’s clothes in his own laundry bags. I knew nothing about this, but I wasn’t surprised at the fact that Ori did these things. Because that’s how he was. And he did everything quietly.”

Captive Audience

Throughout the nearly yearlong saga, Elchanan Danino was hardly able to give interviews. Ori was once an officer in an elite IDF unit, and the defense establishment was deeply worried that if Hamas discovered that, Ori would be tortured to extract information about IDF operations.

As the months of captivity went by, Ori’s family was kept abreast of his condition.

“Every three weeks or so,” Elchanan relates, “we would get an update from the security officials that our son was alive and all right. Maybe we’ll be able to say more later, but we know one thing with certainty — until the end of last week, our Ori was alive and well.”

After the levayah, Elchanan received a phone call from Prime Minister Netanyahu, who expressed his condolences and asked forgiveness.

“We didn’t accept his apologies,” the father said, “but there is a certain change in the fact that he even asked forgiveness, which is something we did not see with him for a long time.

“It says in the parshah of eglah arufah, ‘And they answered and said: Our hands did not spill this blood and our eyes did not see.’ Chazal say about this, ‘Megalgelim zechut al yedei zakkai, good things are brought about through innocent people, and bad things through guilty people.’ I don’t know who is innocent and who is guilty, Hashem will judge. But I cannot say we always felt that he was doing everything.

“I’m not saying, chalilah, that the prime minister committed murder. But I must ask: Could we not have done this differently? Why are our hostages still in captivity? We have the feeling that the deal could have happened a long time ago.”

Given the political alignment of the chareidi parties with the right-wing bloc, an allegation such as this is vanishingly rare to hear in the chareidi world. Yet Elchanan Danino pulls no punches in asserting that the captives have been de-prioritized over the last year.

“I asked the Shas chairman, Aryeh Deri, why only Smotrich and Ben Gvir threaten to dismantle the government, why can’t you threaten the same thing? My rebbi, the Rishon L’Tzion Rav Yitzchak Yosef, ruled at the levayah: ‘Pidyon shevuyim before everything!’ His father, Rav Ovadiah, said the same thing. So why don’t our representatives address this? It’s hatzalat nefashot in every sense!”

Faith and Fate

Given the anguish of the past year, what has kept the Danino family afloat? “I got a certain emotional strength, to know and believe that everything is from Him,” he says. “I know that the human body is a ‘davar ha’aved,’ it is mortal and finite, but spiritual things, the middot and good deeds, are what last for eternity.

“Ori suffered for 11 months in captivity, and I thank Hashem for the gift we received for 25 years. We need to be grateful for life, nothing can be taken for granted. Every moment is a miracle. Suddenly, when it’s not there, you realize that every minute is significant.”

There is a constant stream of people at the shivah at the shul on Geneo Street in Ramot Gimmel, Jerusalem, which is a window onto the proportions of this war. Here, one sees the broad circles that surround each victim. In every corner, there are groups of people huddling around the family members.

The visitors are all astonished at the fortitude and strength exuded by Ori’s parents. When Reb Elchanan is asked if he has questions for Hashem, he says, “We don’t ask questions on our Father.” Then he explains.

“We all have difficulties, and I won’t deny that we’ve also had moments that were too hard to bear,” he says. “I don’t wish it on anyone in the world to go through what we went through. It’s horrific. There is no day or night. But I know that everything Hashem does is for our good. There have been moments when we broke, we had serious doubts that gnawed at our insides. But we don’t understand the calculations of Shamayim. Emunah does not necessarily have to correspond to our emotions.”

After Ori Hy”d was abducted, Reb Elchanan bought a new garment on which to say shehecheyanu at the celebration for Ori’s return.

“My aspiration always was to be among those in the Holocaust who sang before they went into the gas chambers: ‘Nur emunah, nur emunah.’ How can we fathom such a declaration at such a hard time? I’m trying to follow their way and say, despite everything, nur emunah.

“Ori was our oldest son, and our personal feeling is that he was also a korban. Now we daven that his death should not have been in vain, and that from all this, Am Yisrael should come out stronger.”

Unity Is Key

That strength, says Ori’s father, is to be found in unity. At the beginning of the war, Israel was a united country — consolidated by mourning and fear. That togetherness has long-since given way to infighting.

“It’s as if this whole catastrophe didn’t happen. We have to reset, to understand that without unity we have no future.”

Elchanan Danino’s almost unique status as a chareidi father of a hostage among many secular counterparts has given him perspective on the possibilities of bridging Israel’s deep divides.

“In recent months, when I, a chareidi person, was with parents of other hostages — I saw that all hope is not lost, and yes, we can live together in peace and unity. We do not have to think the same way on every matter, but we can always reach agreements, or at least show willingness to do so.

“We’re allowed to argue, and sometimes there’s no choice and we have to argue. But it seems sometimes that we’ve forgotten we’re all part of one nation. Our fates are intertwined. We live in the same land, under the same threats. None of us is exempt from this. We are all Jews.”

While that is a recipe for co-existence for all sectors, Elchanan Danino has a message for his own community in particular. “We have emunah that supports us during the most difficult moments, and we also have Torah and mitzvos that illuminate our lives. Outside our communities, there is a broad Israeli public that does not know all this, and it’s a shame. Think of what we can accomplish if we show them our way of life.”

Despite the bitterness and his own unheeded cry for the government to act on behalf of the hostages, Elchanan Danino wants to conclude on a positive note.

“Our Ori always smiled. We couldn’t find a single picture of him not smiling. Despite everything, I tell Am Yisrael: be happy, be cheerful to one another, increase unity. Even when it’s hard and it hurts, say Mizmor L’todah. Children are a gift — thank Him for the gifts He has given you.”

“I don’t question why this is happening to me and my family. But I wake up every morning and thank Hashem for choosing to put me in this situation. I merited being tasked with this nisayon.”

By Elana Moskowitz

T

his is how Einav Danino began her speeches to countless groups who packed shuls, schools, and auditoriums across the world, people who thirsted for her words of unvarnished faith, and garnered strength from her resolute belief in Hashem’s goodness.

Her son, Ori Danino, was abducted on October 7 from the festival in Re’im, and languished in Hamas captivity for 11 months before he and five other hostages were ruthlessly murdered in Gaza.

On the fifth morning of shivah for Ori, Einav sits curled-up on a low-slung couch in a corner of her living room. The brilliant September sun does not shine through the doorway of her home, in seeming deference to her loss, but even in the dim space Ori’s presence is palpable. Countless pictures of him adorn the room, watercolors, charcoal renderings, penciled likenesses of his laughing eyes and dazzling smile. His hostage poster, declaring, “Bring Ori Home,” abuts a framed photo of him, emblazoned with, “My heart is in Gaza.” But most striking is the silver-lettered, five-foot-tall text of Mizmor Lesodah affixed high across the room, lending unmistakable context to it all.

“The most important thing for us to understand is that we have a Creator Who is our Father, and a father never harms his children. Everyone endures suffering in their lifetime, but if we recognize that our Father is at our side through it all, we’ll realize that what we experience as bad only appears to be so. Right now, from our limited vantage point it seems bad, but it’s actually not. Hashem will eventually show us how it was, in fact, good.”

These are Einav’s first words, and they comprise one of the core messages she imparted to multitudes throughout her 11-month ordeal.

“Someone asked me, ‘Your son is a hostage in Gaza, how can you thank Hashem?’ But I see that Hashem has been with me the entire time,” Einav avers, even as she ticks off a list of incomprehensible challenges she’s had to endure since Ori’s capture.

As a qualifier, she invokes one of her oft-spoken mantras, a quote from the Pele Yoetz, popularized as a song by Yaakov Shwekey.

“I know that ‘ein davar ra yoreid min haShamayim’ — nothing bad descends from Hashem.”

Spiritual Energy

Einav’s renown in the Jewish world evolved from the inspirational talks she gave during Ori’s captivity to garner spiritual merits for her hostage son. She made the transatlantic journey from Israel to America, and beyond, seven times in ten months, often managing to squeeze in five to six speeches a day. Her talks were raw, unscripted missives from the heart, declarations of staunch belief in the goodness of Hashem and love for His children, even in circumstances beyond our comprehension.

In the broad landscape of hostage parents, Einav was an outlier. Instead of investing time and effort in protests, lobbying, and other political activities, Einav focused her efforts on spreading words of emunah, convinced that strengthening others was the way to bring Ori home.

“I wasn’t really involved in the hostage headquarters, I wanted to do something more spiritual. I felt that bringing others closer to Judaism, strengthening their emunah, is what would safeguard and protect Ori, and I believe that’s what he would have wanted me to do. Even initially, before I started speaking publicly, I avoided the whole protest scene. Instead, we went to strengthen soldiers and visit the wounded in hospitals. I know that’s what Ori would have done.”

“Speaking is what gave me strength,” she says emphatically. “It gave me spiritual energy.”

Her unconventional choice branded her an outsider to the other hostage parents. “I was really uninvolved with them, but that was my preference. Other people tried to convince me to join them, telling me, ‘It will be good for you,’ but even when I was there briefly, I felt like I didn’t belong, it wasn’t my place. The only time I participated in something was at the Ohel Tefillah at Hostage Square, where we davened for the hostages, but that was something spiritual.”

Einav admits that her decision came at a price. “It was sad to be alone, to feel you’re missing out on something, that on the one hand you’re a part of this group of parents, but on the other hand you’re not. But when I considered joining them, I encountered protests. I asked myself, what am I doing here?”

Her otherness also had its advantages.

“Feeling that I was not part of them compelled me to do more of what I felt would help Ori and keep him safe; it induced me to give more chizuk, more speeches.”

The logistics behind the more than 100 events Einav participated in were overseen by a man whose combination of an oversized heart, calm pragmatism, and can-do attitude made him the ideal candidate for the job. David Hillel, a New Jersey-based businessman, first met Einav through long-time friend Yaakov Shwekey. When Shwekey came to Israel on a chizuk mission early in the war (see Mishpacha Issue 986, “We Won’t Stop Singing”), Einav reached out to him for help obtaining information on Ori’s whereabouts; at that early stage, all she knew was that he’d been abducted, and she desperately wanted clues on a trail run cold. David accompanied Shwekey to this initial meeting, and immediately intuited what Einav truly needed.

“Here was a frum woman who wasn’t interested in participating with the other hostage families in their activities. At that early stage, there weren’t yet tefillos and hafrashos challah taking place across Israel, and she didn’t really have a place to be. She was sitting home alone all day long, soaking her Tehillim with tears. The other hostage mothers had each other, but she had no support.”

He suggested she come to America, offering to arrange events to share her message of emunah and strength, as a zechus for Ori’s return. Initially, Einav demurred. She’d never been to America before and making the trip now, with her son in captivity and scant information on his well-being, just didn’t make sense. However, within a few days she contacted David, telling him she’d reconsidered and wanted to take him up on his offer. She asked if he’d fly her in along with three supportive friends and her 11-year-old daughter, Hodaya.

With the support and planning of Elliot and Chavi Mandelbaum, Yaakov and Jenine Shwekey, and Chaya Bender, Einav spoke at her first event, a gathering of over 1,000 women in Lakewood.

“And from there, it just snowballed,” David recalls.

David credits many people with the success of these events, praising the flexibility and readiness of rabbanim, principals, and teachers to slot Einav’s visits, even in the eleventh hour.

“I called Yaakov Majeski from Los Angeles, and said, ‘I’m coming tomorrow with Einav, can you set up places for her to speak?’ And he said, ‘Absolutely!’ ” By the next day he had set up 11 venues for her.

“Even when Einav returned from a trip abroad, her immediate concern was, ‘David, when can we do more maasim tovim for Ori, how can we earn him more zechuyos?’ That’s all she wanted to do.”

Gift of Faith

At a certain point, even if she would have wanted to join the other hostage parents, Einav was simply too busy to participate in anything else.

“I did the Israel-America route like it was a trip from Jerusalem to Beit Shemesh,” she recalls. “But I did it because I believe that strengthening others in their emunah is what protected Ori. It’s what kept him alive for eleven months.”

Einav’s speaking tours took her along the Eastern seaboard and across America, all the way to the Pacific coast. Her travelogue reads like a cross-country road trip: Monsey, Monticello, the Five Towns, Manhattan, Lakewood, Deal, Silver Spring, Miami, Boca Raton, Cleveland, Utah, Arizona, and Los Angeles were all stops on her itinerary. She even visited Buenos Aires, Argentina.

“The people in Buenos Aires were so completely unaffiliated, I think there may have even been some non-Jews there who came to hear my story.”

She visited Modern Orthodox institutions, Bais Yaakovs, chareidi schools, and gatherings of people so far from Judaism — she taught them to say Shema Yisrael by having them repeat after her, word for word.

“The first time I went, I intended to stay for two weeks, but I ended up staying for a month and a half. The chizuk I was able to impart, and my belief that this is what’s protecting my son, is what kept me there, and it’s what kept bringing me back.”

These speaking engagements both infused Einav with the purpose and resolve so vital to her well-being, and added untold spiritual merit to her son. However, the true beneficiaries of her talks were the people who came to hear her speak.

In personal accounts, videos, and pictures of Einav’s speeches and hafrashos challah, the men, women, teenagers, and tweens cry, sing, and listen in rapt attention as Einav speaks of Ori, of emunah, of “Ein davar ra yoreid min haShamayim.”

Arms interlocked, high school girls and grown women swayed to the sound of violins, keyboard, and guitar as they sang “Acheinu,” “Hinei Lo Yanum,” and “Ani Ma’amin.”

In shuls across the States, endless lines snaked around wooden pews as people patiently waited hours for their turn to cry with Einav, daven for Ori, and thank her for her gift of emunah.

In an especially moving video, a girl with special-needs promised Einav, “I’ll come to Israel and get your son back!” In another, a wizened Holocaust survivor conveyed, “What you say about Hashem, I know this feeling… I really feel for you, Einav, because I know. I went through it, too.”

Girls hugged her through their tears, boys asked for brachos and grown men sobbed.

However, the most heartbreaking scene of all unfolded when Einav partnered with Roi, a survivor of the October 7 massacre. Eleven-year-old Hodaya approached Roi, and in tears, asked him if he’d seen her brother, Ori.

Her efforts to spiritually strengthen her brothers and sisters were clearly not in vain.

“Some people in the schools I visited decided to start wearing tzitzis, others chose to start laying tefillin. Still others committed to respecting their parents more. Women accepted the mitzvos of taharas hamishpachah and lighting Shabbos candles. People started keeping Shabbos. I have a suitcase full of kabbalos that people took on for Ori’s zechus. I even had rabbanim tell me that my emunah induced them to take stock of what they have to improve in their own emunah.”

At events, when she was asked, “What can we do for Ori?” her answer was vintage Einav. “Find something in your life that’s not so good, and thank Hashem for it. It’s easy to thank him for the good things, but we have to know that even what seems to be bad is really good.”

Ori’s personal example was the catalyst for many kabbalos as well. “Ori never let anyone feel they were less than him, he didn’t believe it was the case. And he always thought of other people first and himself last. Even as a child, he would first give candy to his siblings and then take for himself. When he got older, he’d even give a new article of clothing he’d bought for himself to his brother. They say, ‘If you don’t love yourself, you can’t love another,’ but Ori loved others first, and himself second.”

This sentiment was evident in the dramatic circumstances of Ori’s capture. Ori had already escaped the festival in his car, when he insisted on turning back, driving directly into the slaughter. He was determined to rescue three friends he’d met only the day before. Itay and Maya Regev, siblings who were released in the November hostage deal, owe their lives to Ori, as does Omer Shemtov, who is still languishing in Gaza.

Einav had no illusions about Ori’s captivity. “When I saw the first two hostage releases, I had a small ray of hope. But I slowly came to realize that as the highest ranking active-duty officer in captivity, he wouldn’t be released so quickly. I figured he’d be one of the last. We tried to hide the fact that he was a soldier from Hamas, but I believe they knew. And even if they didn’t know, as a male over 18, he was a valuable commodity for Hamas. I assumed he’d be saved as a bargaining chip until the very end.”

Despite her realism on the slim prospects of Ori’s early release, Einav didn’t ask Hashem, “Why?”

“Even when I heard he’d been taken hostage, I didn’t ask Hashem, ‘Why Ori?’ If He took Ori, it means He chose me for this nisayon,” she says with conviction. “My focus has always been on accepting that Hashem charged me with this duty, and it’s my responsibility to do the best I can.”

Seeing the Good

A small, slight woman sits next to Einav nodding along, her intense blue eyes tearing up when Einav shares something particularly poignant. She appears to be utterly in sync with every word Einav utters, as if she’s co-opting some of the pain, if only it will mitigate Einav’s suffering. This is Ilana Moskowitz [no relation to the writer], a Five Towns, New York native, who was introduced to Einav through a friend, and has accompanied her on the bulk of her odyssey. She has followed her around the States from lecture to lecture, translating her words into English. Ilana is also an example of how Einav’s surging emunah cascaded to envelope those around her in a greater sense of Hashem’s Presence and love.

“Einav has infused our culture, our society, with the boost of emunah we needed during this tragic year,” Ilana begins emphatically.

“I think many people struggle with emunah. They won’t say it, but inside they’re thinking, ‘Every day is another tragedy, why is Hashem doing this?’”

For Ilana, Einav’s ability to see the good, the Mizmor L’sodah in apparent evil, was a game changer.

“Everything she does is infused with gratitude to Hashem. Einav wanted to see Ori’s car, the place he was abducted from. Initially, he army officials told her ‘lo kedai,’ it’s not a good idea to go, you’ll see terrible sights there. But she insisted, so several policemen escorted her to the lot with all the burned-out cars from the festival. When she got there, she saw the carnage —cars torched beyond recognition — and she was blown away. ‘How could anything come out of here alive?!’

“Then she asked to see Ori’s car, and it was bullet-riddled, smashed, not a spot without a bullet hole, and what was her reaction? She cried out to Hashem, ‘Mizmor L’sodah!’ The cops escorting her started sobbing,” Ilana relates with wonder.

“I said to her, ‘How did you do that? How did you thank Hashem there?’ And she answered, ‘I looked at all the other cars, they were burned beyond recognition. You couldn’t have gotten out of there alive. Ori’s car only had bullet holes. He was able to come out alive.’”

Despite her outsized role as Einav’s support, Ilana refuses to take any personal credit. “I am selfish, Hashem sent me Einav for my emunah. I needed the chizuk! People underestimate what it means to be able to believe from a place of tragedy. How do I question Hashem’s ways when I have Einav, whose bechor was taken captive for almost a year and killed, and she’s still able to thank Hashem for choosing her to weather this nisayon?”

Ilana shares another example of Einav’s emunah. “We were in Cleveland one night, and I asked Einav something I can’t believe I had the audacity to say: ‘Einav, do you really believe Ori’s alive?’ And she answered me, ‘Of course, 100 percent.’ Such emunah! And you know what? She was right the entire time.”

Einav had an elaborate seudas hoda’ah planned for Ori’s return. “She had everything planned down to the color of the napkins,” David Hillel says. “The community in LA made her promise to bring Ori to visit them when he returns, not if he returns. That was the level of emunah she imparted to them.”

“She saved every note, every picture, every kabbalah someone took on, and she planned on showing Ori every single one when he got out. To show him the zechuyos that brought him home,” Ilana reveals.

Core Belief

Einav’s last speaking event was at a Yaakov Shwekey concert in Deal, New Jersey, with 6,000 participants. She returned to Israel on Friday. That Motzaei Shabbos she learned that Ori was gone.

No one envisioned it would end this way.

“I’m disappointed, I can’t lie,” David Hillel admits, “especially because we had clear confirmation that he was alive just a week earlier. It’s been a very painful journey.”

What happened to all the tefillos, the kabbalos, the emunah? Weren’t they supposed to bring Ori home, safe and sound, to celebrate with an epic seudas hoda’ah?

But even here, in this place of dreadful certainty, Einav’s emunah prevails.

“Hashem gave me a pikadon, a deposit, and I returned the pikadon to Him. I finished my shlichus as Ori’s mother. I believe that after all Ori suffered over the last eleven months, he’s now in the best place. This comforts me,” she says through tears.

“I don’t believe we squandered the opportunity to save him or that anything was in vain. I can’t know what all the tefillos did for the hostages in Gaza, or for us, or in Shamayim. And it was my zechus to have facilitated it all.”

And here, Einav offers another perspective on Mizmor L’sodah, another iteration of gratitude from the nadir of pain.

“Ori was buried on holy soil, here in Eretz Yisrael. Not everyone merits that. There are people crying to have their children back for burial. And I had the zechus that after eleven months in captivity, Ori was buried immediately after his death. Don’t you understand this was a zechus?”

“He was murdered on Thursday, he was on holy soil by Motzaei Shabbos, and he was buried on Sunday. V’shavu banim ligvulam. I see with utter clarity that Hashem hasn’t abandoned me.”

Einav saw Ori one final time, immediately preceding his burial. “People told me not to look at him, but I’m so happy I did. He was like a porcelain doll, entirely unblemished, aside from the bullet wound. It’s astounding that he could look this way after eleven months in captivity. And there was this light that emanated from him, he looked so peaceful, angelic, like a malach bidding me farewell and rising to Shamayim.”

Reflecting on the last 11 months, David Hillel is proud of how American Jewry showed up for Einav. “They were just unbelievable. Whenever we ran an event, no matter what day of the week it was, people came. American Jewry just came together to give her a big hug.”

And he believes that this is only the beginning for Einav. “I think from all her suffering, Einav is going to evolve into one of those inspirational people who have been through the worst, yet are still singing Hashem’s song.”

And if that song is Yaakov Shwekey’s “Ein davar ra yoreid min haShamayim,” he may indeed be right.

“Yaakov Shwekey was menachem avel Einav on Facetime and he sang her ‘Ein davar ra yoreid min haShamayim,’ ” David shares.

“Yaakov said to Einav, ‘I’d never have the chutzpah to sing ‘Ein davar ra yoreid min haShamayim’ to anyone else who’s sitting shivah, but I’m singing it to you because I know that’s what you’re thinking. I know that’s who you are.’”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1028)

Oops! We could not locate your form.