Rav Meisel’s Sefer

| May 20, 2025Rav Meisel pulled out promissory notes from his pockets for loans he had signed and said, “This is my sefer”

P

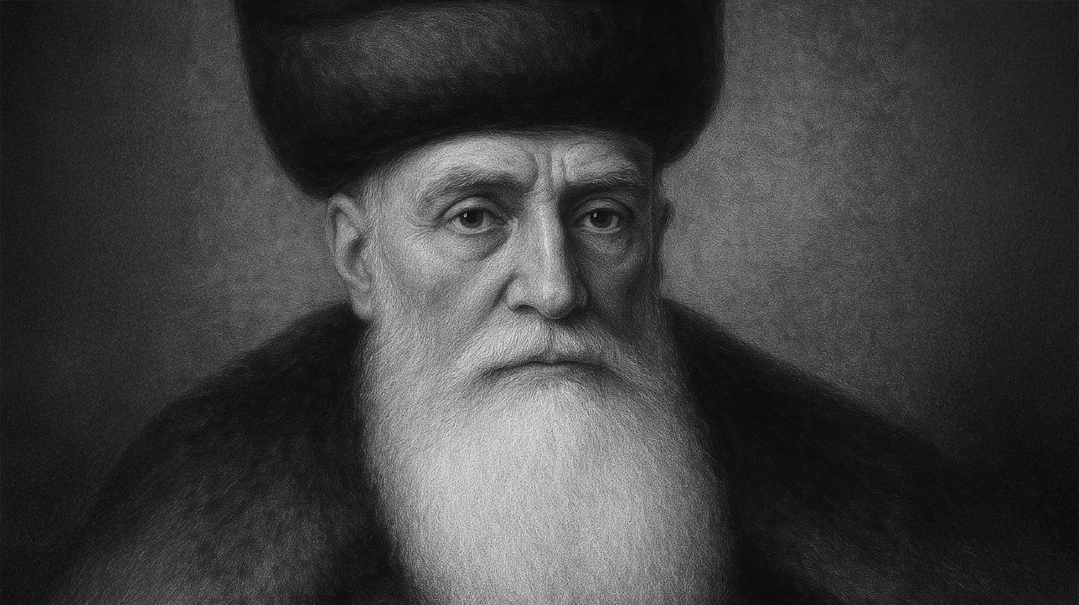

esach Sheini, the 14th of Iyar last week, marked 113 years since the passing of Rav Eliyahu Chaim Meisel z”l — scarcely known today, in part because he wrote no seforim, yet he was one of Poland’s most renowned rabbanim before World War I.

Rav Meisel’s leadership was in great demand; the great cities of Poland vied for him to be their rav. In addition to his tremendous Torah scholarship, Rav Meisel’s hallmark traits were his concern for Klal Yisrael, his drive to build needed institutions, and his care for every individual Jew. He was a litvishe gadol who was beloved by chassidim.

His brilliance was phenomenal. At the age of eight, he became the youngest boy to be accepted to Volozhin — younger even than the Beis HaLevi, who was accepted at age ten, and the Netziv, admitted at age 11. At 13, Rav Meisel was given semichah to pasken halachic sh’eilos.

Rav Meisel was born in Horodok, near Vilna, in 1821. His father, Reb Moshe Meisel, was a wealthy businessman. His love for Klal Yisrael was already apparent as a youngster. Polish merchants would visit his father to discuss business matters. One of these merchants once engaged Eliyahu Chaim in conversation.

“Would you prefer to go to heaven or purgatory?” asked the merchant.

“Who goes to each place?” asked the boy.

“Rich Poles go to heaven and Jews go to purgatory,” the merchant replied.

“I would prefer to go to purgatory with the Jews than heaven with Poles,” Eliyahu Chaim retorted.

At 19, Rav Meisel became the rav of his hometown of Horodok, where he remained from 1840 to 1843. He strongly felt a rav needed to teach Torah, lead the community, and establish places of chesed and tzedakah — all of which he did in Horodok. Within a short time, Rav Meisel’s reputation spread.

In 1843, Rav Meisel was offered the position of the rav of Deretchin. Rav Meisel believed a rav should stay in a community as long as he felt his leadership was needed. If he had already accomplished what needed to be done, then it was time for him to lead another kehillah. In the Deretchin community, Rav Meisel demonstrated outstanding spiritual and communal leadership, as well as his trademark chesed and kindness, for eight years.

Rushing to Help

In 1861, Rav Meisel moved on to become the rav in Pruzhany. There, his hachnassas orchim became famous; he personally ensured every guest had pillows, blankets, and food. After seeing how worn out a visiting talmid chacham’s shoes were, Rav Meisel gave his guest his brand-new shoes.

While Rav Meisel was in Pruzhany, there was an outbreak of a terrible illness. An essential part of the cure for this illness was constant massaging of the sick person. Rav Meisel immediately organized groups of people to provide massages to the sick. Whenever Rav Meisel heard that someone was ill, he rushed to the person’s home and massaged the patient himself until others could be organized to help.

Once, when Rav Meisel was rushing to a sick person’s house, his boot became hopelessly stuck in the mud. He extracted his foot from the boot and continued on with only one boot.

The epidemic was still raging when Yom Kippur arrived. After Ne’ilah and Maariv, Rav Meisel walked from home to home, taking care of the sick. In the morning, people on their way to Shacharis found Rav Meisel on the porch of the last house he had visited, collapsed from exhaustion.

In 1867, confident that what he had established in Pruzhany could be carried on by others, Rav Meisel became rav in Lomza. There, he learned to speak Russian, using his fluency and influence to help the community — especially with regard to saving Jewish soldiers from the Russian army, a spiritually and physically dangerous environment due to widespread anti-Semitism.

The price of freeing a Jew from army service was 400 rubles, and Rav Meisel established a fund specifically to help cover the expense. The individual’s family would pay half, and Rav Meisel’s fund would pay the other half.

Raising these funds was not easy. Once, on Yom Kippur evening, Rav Meisel announced that Kol Nidrei would not begin until a large amount of money was collected to free boys from the Russian army. Recognizing that the rav was serious, the kehillah raised the money.

The situation worsened as time went on, and the Lomza kehillah ran short of resources to save the soldiers. Rav Meisel appealed to Lodz, as it had a larger and wealthier Jewish community. Seeing their chance, the Jews of Lodz asked Rav Meisel to become their rav.

Feeling Their Pain

In 1877, Rav Meisel became the chief rav of Lodz, Poland’s second-largest city, and it is in that role that he is still mainly remembered today. This was the golden era of his leadership, and the Lodz Jewish community grew from 10,000 to approximately 160,000. Lodz was a city deeply involved in the textile industry, and the Jews of Lodz ranged from the factory owners to the factory workers.

One year before Pesach, Rav Meisel worked to arrange leave for Seder night for 12,000 Jewish soldiers in a nearby camp. On Erev Pesach, Rav Meisel learned that 2,000 of the soldiers had not been granted leave.

Rav Meisel decided not to start his own Seder or even enter his own house until he had tried to get the remaining soldiers out. The general who could grant them leave was in an army camp closed to civilians.

Rav Meisel traveled there with another community leader, and, seeing the camp was completely closed off, Rav Meisel jumped over the fence. A guard ran over and was shocked to find that the intruder was an elderly man in rabbinical garb.

Rav Meisel said he wanted to request leave for 2,000 Jewish soldiers for Passover. He was brought to the general, who demanded, “How dare you enter this camp?”

Rav Meisel began to weep, and explained that the plight of the 2,000 soldiers left him broken. The general was so moved that he granted them leave. Rav Meisel finally returned home and began his seder at four o’clock in the morning.

As rav, Rabbi Meisel persuaded wealthy individuals in Lodz to build an orphanage, a home for the elderly, a Jewish hospital, and many schools. He also raised money for thousands of Jews from other communities.

During an especially freezing winter, Rav Meisel was raising money for firewood and visited the home of a banker named Reb Isaac. An attendant opened the door and invited Rav Meisel inside, but Rav Meisel insisted he would wait outside to speak to Reb Isaac.

When Reb was told that Rav Meisel was waiting for him outside, he rushed to the door. When he saw the rav standing in the cold, he urged him to come inside. Rav Meisel politely refused and began explaining why he had come. At this point, Reb Isaac was becoming very cold.

“Please, Rebbi,” he said, “just come in. I’m freezing.”

But Rav Meisel wouldn’t move, and while the banker shivered, he spoke about the urgent need for wood to heat the homes of poor families.

Finally, Reb Isaac cried, “Rebbi, I will give you anything you want. Just please come inside.”

This time, Rav Meisel acquiesced and entered. He sat down and said, “I need firewood for 50 families.”

“Rebbi, I will give the firewood,” Reb Isaac replied. “But you know I give tzedakah. Why did you make me stand outside?”

“Reb Isaac, I know that you give,” said Rav Meisel. “But I need you to understand what poor people are going through. You get a better perspective hearing their plight while standing in the freezing cold than in the warmth of your home.”

Rav Meisel also built a textile factory to employ people, and to help Jews who were fired from gentile textile factories.

At one point, Rav Meisel needed 20,000 rubles to pay off the debts his tzedakah fund had incurred through helping so many people. Although they had supported Rav Meisel until then, this time the Jews of Lodz balked at the considerable sum.

This opened a door for the Jews of Bialystok, who wanted Rav Meisel as their rav. Bialystok said they would pay the debts on condition that Rav Meisel became rav of their city. On the day the delegation from Bialystok was scheduled to come, one of the prominent members of Lodz gathered the other wealthy people.

He told them, “Rav Meisel deserves to have us pay off all of his debts and even add another 40,000 rubles, just to keep him with us.”

The others agreed, the debts were paid off, and Rav Meisel remained with the Lodz community.

Practical Wisdom

The custom in Lodz was that Rav Meisel was honored with the sixth aliyah on Shabbos, and other talmidei chachamim of the community were honored with the third.

It once happened that an uncouth man became very wealthy. He proudly purchased a seat on the mizrach wall and flaunted his wealth in other ways. One week, he told the gabbai that his birthday was on Shabbos and that he wanted to receive shishi, the sixth aliyah. The gabbai apologized and said shishi was going to the Dayan, but the man would be given the fifth aliyah, chamishi.

“Absolutely not,” the man insisted. “I will have shishi.”

The gabbai would not be intimidated, and when Shabbos arrived, this man was called for chamishi. The man walked to the bimah and then turned to the gabbai and punched him in the face. Bedlam broke loose, and after Shabbos, the gabbaim met with Rav Meisel.

The gabbai who had been punched suggested to Rav Meisel that the shul abolish kibbudim for aliyos and follow a random order, to prevent further fights over demands for honor.

All present thought this was an excellent idea — except for Rav Meisel.

“It is a tragedy when people come to the shul looking for honor,” he said. “But it would be even worse if people stopped looking for honor in the shul and pursued it elsewhere. This pursuit of honor also drives individuals to give time, energy, and money to the community and the shul.”

And so the status quo remained.

Once, Rav Meisel passed a prominent businessman. He asked the man how things were, and the man began loudly describing the difficulties he was coping with, a dishonest partner, unreliable employees, increasing taxes, and so on. Rav Meisel gave him a brachah for hatzlachah, and the two parted. A few months later, Rav Meisel met the businessman again and asked how things were going.

This time, the businessman said calmly, “Everything is good.”

With his quick wit, Rav Meisel responded, “This reminds me of the Midrash in parshas Ki Savo. On the pasuk, ‘I now bring the first fruits of the soil which You, Hashem, have given me,’ the Midrash says, ‘A person gives praise in a soft voice, and says complaints in a loud voice.’ ”

Rav Meisel pointed out that when complaining, this man was very vocal and detailed, and now when things were positive, he was quiet and succinct. One should thank Hashem with passion, and with specifics, too.

Legacy

Rav Meisel was niftar on Pesach Sheini (May 1, 1912) and was buried in the Lodz beis hakevaros. The love Klal Yisrael had for him was abundantly apparent in the crowd of more than 100,000 who accompanied at his levayah — possibly the largest in the Jewish history of Eastern Europe.

Once, on meeting Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, Rav Meisel praised his recently published sefer, Achiezer.

Rav Chaim Ozer asked Rav Meisel, “When will you write a sefer?”

Rav Meisel pulled out promissory notes from his pockets for loans he had signed and said, “This is my sefer. I am so busy with tzedakah that I don’t have time to write a sefer.”

“My sefer pales in comparison to yours,” Rav Chaim Ozer declared.

The legacy of Rav Meisel’s sefer, and his life, continue to inspire.

Rabbi Menachem Levine is the CEO of Chicago’s JDBY-YTT, the largest Jewish school in the Midwest. He served as the rav of Congregation Am Echad in San José, California, from 2007 to 2020. He is a popular speaker and writes for numerous publications.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1062)

Oops! We could not locate your form.