Rav Boruch Ber Rediscovered

Soon after Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz was buried in 1939, the Jewish community of Vilna was destroyed and his unmarked grave forgotten. But then, 70 years later, a little girl’s sudden deformity led to a series of seemingly unrelated events that resulted in the discovery of his resting place. This week, on the Torah giant’s 75th yahrtzeit, the Torah world will gather to honor his memory

His talmidim gathered around his deathbed, waiting for a bit of instruction, a last sign, but the Rosh Yeshivah’s thoughts were elsewhere.

“The Rebbi is coming!” whispered Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, the rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Knesses Beis Yitzchak in Kamenitz. “I must wash my hands in honor of the Rebbi!”

“The Rebbi” could refer to only one person. Throughout his life, it seemed as if Rav Boruch Ber had never left the benches of the beis medrash of Volozhin, and had never stopped quoting the words of his rebbi, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik. “The Rebbi” was at the center of Rav Boruch Ber’s life.

Now, on the 5th of Kislev, 5700 (1939), Rav Boruch Ber faced his final hours. The Nazis had already invaded Poland and Jews everywhere had fled in panic and confusion to one of the safe spots, Vilna. Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz and other Torah scholars had also fled to the Lithuanian capital, where Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky, the leader of Diaspora Jewry, had greeted Rav Boruch Ber and asked him to open a yeshivah for the masses of refugees.

But Rav Boruch Ber’s stay in Vilna did not last long. Already in his 70s, the Torah giant was ebbing away. He asked his students to accompany him in those last moments — and there they stood.

“The Rebbi is coming,” he whispered, frightening his talmidim. It seemed as though he could sense his rebbi, who had died in 1918, waiting for him in the Heavenly realm. “I should put on a new shirt, something clean, in honor of the Rebbi,” he said. He further requested that an empty chair for his rebbi be placed at his bedside.

Rav Boruch Ber prepared himself for his petirah like a person preparing for a lavish repast. “Review the shiur,” he begged his talmidim. They looked at each other in astonishment. Review the shiur? Now? Who could do such a thing?

One of his students, Rav Meir Pantel, mustered up the courage to begin reviewing the shiur aloud. As he listened, Rav Boruch Ber’s face lit up, angelic, as he heard for the last time the teachings of his master, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik.

When the shiur reached its conclusion, Rav Boruch Ber recited the brachah of Ahavah Rabbah and the pesukim of the “Hallelukahs.” Then he fell silent. After a moment, he cried, “V’shavti b’shalom el beis avi!” And his holy soul departed.

With that, the Torah world was plunged into mourning.

A Fateful Request

Thousands of miles away in Bnei Brak, the Chazon Ish received the news and collapsed to the floor in tears. The great Rav Chaim Brim approached the Chazon Ish, tearing his clothes and sitting on the floor like a mourner. “When Rav Boruch Ber was alive, his toil in Torah study shielded the generation from harm. Now who will protect us from our enemies?”

The fifth of Cheshvan, 5700, was a bitterly cold day, but people of the Torah world, fearful of their fate, gathered in the streets near the yeshivah and walked Rav Boruch Ber to his final rest. They could still feel his burning love; there were many times in his life when he had given away the last of his food to a poor Jew. His sole concern in life was the welfare of others. “When I come before the Heavenly Court,” he used to say, “they will look to see what I have brought with me. Torah? Whatever I have learned can’t really be called Torah. Yiras Shamayim? Is my yirah even worthy of the term? But there is one thing that I will be able to tell them: I loved every Jew, and whenever I saw another Jewish person, all I thought about was what was good for him.”

The massive funeral procession, made up of thousands of yeshivah students and gedolei Yisrael, made its way toward the main shul of Vilna. The Brisker Rav walked the entire way with a bent posture, ignoring the pleas of those around him to sit in a car or wagon. “We are accompanying a gaon from another world to his final rest,” he said. “Rav Boruch Ber was a gadol of a caliber that has not existed for 200 years.”

As the procession neared the cemetery on Zaretcha Street, the men of the chevra kaddisha tensed up. For 25 years already, this cemetery — where over 70,000 Jews had been buried (including such illustrious Talmudic commentators as the Rashash and the Cheshek Shlomo) had been filled to capacity. No other graves could be dug, not even a place for a piece of parchment from a sefer Torah. But Rav Boruch Ber’s final words continued to echo in their ears: “V’shavti b’shalom el beis avi — I shall return in peace to the house of my father.” It was seemingly a request to be buried near the grave of his father, Rav Shmuel Dovid.

The mara d’asra, Rav Chaim Ozer, asked the chevra kaddisha to do everything in their power to bury Rav Boruch Ber alongside his father. “There is only one slim possibility,” they told the rav. “There is a path that runs near the kever of Rav Boruch Ber’s father. We can break into a portion of that path and bury him next to his father’s grave.” Rav Chaim Ozer ruled that they should do so, and Rav Boruch Ber thus became the last person to be interred in that cemetery. He was buried in a highly unusual spot, in what later would prove to be a stroke of incredible Hashgachah pratis.

Mourners covered the improvised grave with mortar — until a tombstone could be erected. But no tombstone was ever placed there. Not long after his petirah, the Jewish refugees in Vilna fled from the city, fearing for their lives as the war rumbled closer.

Bringing Honor to the Torah

Seventy years later, in 2009, a group of girls were playing in the courtyard of a Bais Yaakov school in the western United States, clutching photographs of rabbanim that their teachers had given them.

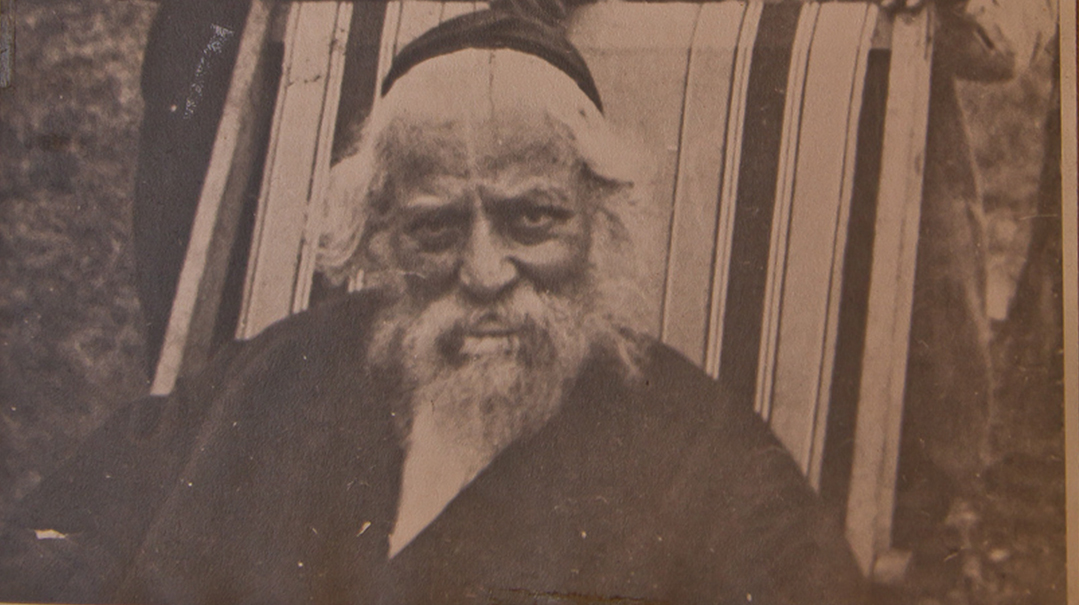

One of the girls held a picture of a man with a snow-white beard, large peyos on either side of his face, and piercing eyes. At her young age, she failed to appreciate the depths of Torah knowledge behind those blazing eyes, and in a moment of pure folly, said: “Look at this! He looks like… a monkey!”

The other girls playing near here showed their disapproval, but soon enough they carried on with their games. A few minutes later, they heard a piercing scream. The girl who had insulted Rav Boruch Ber sat still, her face twisted hideously. She was rushed for emergency medical treatment, but to no avail. Her parents took her to a wide assortment of specialists, but not one doctor could cure her of her disfigurement.

As the family researched the matter, they inquired into what had happened the day that their daughter had contracted this deformity. Finally, they heard that she had used a derisive term to describe a great tzaddik. The parents, Torah-true Jews, instantly understood the reason for her condition. Without a moment’s hesitation, they resolved to show honor to the memory of the Rosh Yeshivah and his Torah.

They soon contacted Rabbi Yisrael Meir Gabbai, the founder of Ohalei Tzaddikim — an organization dedicated to the preservation of the burial sites of gedolim and of Jewish cemeteries — and asked him to arrange for a minyan to visit the kever of Rav Boruch Ber and to ask for his forgiveness.

Rabbi Gabbai and Rabbi Yisrael Gellis traveled from Jerusalem to Vilna and arrived at the Zaretcha cemetery. Over the course of the seven decades that had passed since Rav Boruch Ber’s petirah, the cemetery had faded into history, gradually being built over by the locals. As it happened, the Zaretcha cemetery at the time was slated for destruction. All of this was perfectly legal in Lithuania, where the law permits the destruction of a cemetery that is more than 90 years old. The cemetery could be preserved, but only if it was designated as a historic site. But all that remained there was a small memorial fashioned from tombstones that indicated the former presence of a cemetery on that spot.

The graves were barely visible, and entire tombstones were missing, at some point used by the Communist government for work projects. Hundreds of the stones still make up portions of the stairways in government buildings, and thousands of other stones can still be found in the storehouses of the Jewish community.

The two men examined various maps and consulted with elderly local residents. Eventually, they gathered enough information to determine the general location of Rav Boruch Ber’s grave. The chevra kaddisha’s ledger, of course, contained the names of about 75,000 people who had been buried in the cemetery over the generations — but no one knew the precise location of Rav Boruch Ber. Nevertheless, the two brought a minyan to the cemetery to ask for mechilah. Within days of that highly unusual event, the young girl’s face returned completely to normal. Her parents, meanwhile, did not have an inkling of the repercussions that were yet to result from the story.

Taking Responsibility for the Dead

In Jerusalem, members of the Ohalei Tzaddikim contacted Rav Boruch Ber’s descendants to share the story. The family received the news with a forgiving smile; even a video documenting the events did not overly impress them. But they did learn one thing: the reason for a mysterious telephone call they had received several months earlier, from a Jewish man in America who asked their father, Rav Chaim Shlomo Leibowitz, the Rosh Yeshivah of Ponevezh, to forgive a slight to the honor of his grandfather, Rav Boruch Ber (to whom Rav Chaim Shlomo bears an astonishing resemblance). “I don’t have the ability to be mochel in his place,” Rav Chaim Shlomo replied, suggesting that the caller find out where Rav Boruch Ber was buried and ask for mechilah on his own. The family went on with their lives, and the call was forgotten.

Now, Rabbi Gabbai asked the family to help restore the cemetery and their illustrious forebear’s grave.

“Do you know exactly where he is buried?” the family members asked, but the answer was in the negative.

“We follow the rule that appears in a number of seforim,” Rabbi Gabbai explained, “that if an exact burial place cannot be found, a matzeivah is placed as close as possible, and the neshamah will come to there.”

The family of prestigious talmidei chachamim was not convinced. But then they were shown the full statistics regarding the condition of the cemetery and the potential danger to the place if they failed to act immediately. “If it was a chassidish rebbe who was buried there, and not a Lithuanian rosh yeshivah, there would have been masses of chassidim dealing with the issue by now,” one askan told them, “but in this situation, if you do not act, the entire cemetery will be destroyed.” Already, large buildings were being erected there, and the demolitions were proceeding at lightning speed. The cemetery could only be preserved if the proper permits were obtained to protect it.

This galvanized the family into action. They consulted with Rav Aharon Leib Steinman and Rav Chaim Kanievsky to determine whether they should invest time in locating and restoring their grandfather’s grave and the cemetery in general. The answer was unequivocal: “You should tell people that while we generally have to care for the living and help perpetuate Torah study above all else, this case is different. The honor of Rav Boruch Ber, whose chiddushei Torah the yeshivah world constantly studies from his classic work, Bircas Shmuel, is at stake, as is the honor of the many other gedolim buried there, and that is worth the investment.”

The Final Clue

The work was grueling, and at first, they didn’t make much headway. But then, a new source of information surfaced — an original map of the cemetery, drawn to scale, which was found in one of the historical archives in Poland. A local company was hired to take aerial photographs, and with the aid of various measurements, it soon became possible to gauge the approximate location of Rav Boruch Ber’s burial place. Throughout the process, Rav Boruch Ber’s descendants and their partners recognized that they were accompanied by nearly miraculous siyata d’Shmaya. “It wasn’t natural at all,” said one of the gedolim who observed the process.

The family began questioning Rav Boruch Ber’s students. His great-grandsons, Rav Yaakov Moshe and Rav Uziel — the sons of the Rosh Yeshivah of Ponevezh, who are known in the yeshivah world as illuim in their own right and prodigious marbitzei Torah — spoke with the last three surviving individuals who had attended their great-grandfather’s levayah. Those talmidim (who recently passed away) said that they had walked for about five minutes past the entrance to the cemetery, until they reached the site of the “taharah shtiebel.” It was situated across from a flight of stairs leading to a path near the burial plots: Rav Boruch Ber, they said, was buried alongside that path.

Now all that remained was to locate the remnants of the taharah room, the stairs, and the path. With the help of maps, they were able to pinpoint the location of the taharah room. But the spot itself was just a mound of dirt, without a trace of either the kevarim or the path that had once existed beneath it. The family members knew that even if they managed, miraculously, to find the remnants of the graves, they would still have to figure out some way to identify which grave in the area belonged to Rav Boruch Ber.

But one eyewitness account, which was Providentially brought to them, changed the entire picture. “The Rosh Yeshivah was buried on the path,” one talmid related, “but since it was an unusual burial, his grave is positioned at a right angle to the other kevarim in the cemetery. All the other kevarim run from east to west, but his runs from north to south.” That last clue was the final ingredient for a resolution.

Buried in a Corner

Under the supervision of rabbanim and various experts, they began digging through the layers of dirt and broken tombstones. As soon as they reached the depth of 70 centimeters, the heavy machinery was set aside, and they began digging by hand. Hour after hour, day after day, and month after month, they toiled over the excavation, until finally, the moment of truth arrived.

Suddenly, a flight of stairs appeared before their eyes, along with a path running alongside the rows of graves — and there, on the side, was a single grave positioned differently from all the others, in the middle of the path. Covered with a thin layer of crumbling mortar, this was the burial site of the great Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz.

“We almost fainted at that moment,” said one of his descendants. “In a matter of seconds, we found ourselves looking at the very thing for which we had been searching for so long. For the first time in our lives, we saw the grave of our revered ancestor.”

Their excitement grew when they realized just how miraculous it was that the grave had been preserved. The authorities had demolished all of the graves and tombstones in the area, up to three centimeters from one side of the kever.

Since the grave is located on a slope at the outskirts of the cemetery, the mortar covering it had begun to crumble, and a special permit was granted to cover it with concrete. According to an engineer’s assessment, even more extensive work will be needed to preserve the site. Rav Boruch Ber’s family has used this assessment to petition to build a proper ohel over the great Rosh Yeshivah’s burial site.

At the moment, the efforts to arrange for the construction of an ohel, as well as to fence in the entire cemetery, are still underway. At the community’s request, the fence will be constructed from thousands of uprooted Jewish tombstones, as has been done in other restored cemeteries (such as the one adjacent to the Rema’s shul in Cracow). Those involved asked Rav Shmuel Wosner whether this was a proper practice. He said that not only is it respectful to the deceased, but it is actually a very commendable step, as it will result in the matzeivos being returned to the cemetery and preserving the memory of the deceased.

Vilna, 5 Kislev 5775

Two years have passed since the discovery of the kever. This week, the Jewish world will mark 75 years since the date of the petirah of Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz. Hundreds of Jews from Eretz Yisrael and all over the world will stand at the gravesite of the author of the Bircas Shmuel, a sefer almost every yeshivah bochur in the world has toiled to understand and has delighted in studying. Among the crowd will be some of the most prominent supporters of Torah study in our times, along with the most renowned roshei yeshivah of the generation.

Seventy-five years after his burial, Rav Boruch Ber’s hakamas matzeivah will take place for the very first time. His grave will finally be marked by a tombstone and the same shiur that was reviewed on Rav Boruch Ber’s deathbed will be delivered again by his grandson — Rav Chaim Shlomo Leibowitz, the Rosh Yeshivah of Poneezh, and formerly of Kaminetz — to a group of Torah scholars in Vilna.

This will be the culmination, in a sense, of Rav Boruch Ber’s funeral procession, closing the circle after so many decades. But even now, those holy lips, which never ceased uttering words of Torah throughout the years of war and peace, are still continuing to move in his grave, as his Torah is learned and discussed throughout the world.

Miracles at the Grave of the Vilna Gaon

One of the earliest memories of Rav Chaim Shlomo Leibowitz, the Rosh Yeshivah of Ponevezh, is from the levayah of his grandfather, Rav Boruch Ber. The Rosh Yeshivah’s family members relate that after the levayah, Rav Chaim Shlomo wished to visit the kever of the Vilna Gaon, who is also buried in the Zaretcha cemetery.

But his father, Rav Yaakov Moshe, explained that it is customary to visit the Vilna Gaon’s kever after one has immersed in a mikveh. Because of the freezing temperatures at that time, Rav Yaakov Moshe did not allow his son to perform a tevilah¸ and Rav Chaim Shlomo could not visit the grave.

Since that time, the Vilna Gaon’s kever has been transferred to a different cemetery. In fact, the Gaon’s grave has been transferred more than once. (Various researchers are still trying to determine the exact course of events over the period of more than two centuries since his death.)

On one of the occasions when the Gaon’s grave was moved several decades ago, the remains were placed in an ohel. At that time, the Ponevezher Rav felt that instead of allowing the Vilna Gaon to remain buried in Europe, where his grave would remain under the threat of destruction, his body should be transferred to Eretz Yisrael and reinterred in Bnei Brak, as was done for the Chofetz Chaim and other gedolim. The Rav began making efforts to that end, and newspapers in Israel reported that the deal was near completion — even though Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky had prohibited such a move decades earlier. Of course, at the time, there was no real reason for the transfer; no one dreamed of how terrible the future would be. Ultimately, those efforts failed.

Over the years, it has been widely reported that none of the people who handled the Gaon’s remains lived for more than a year afterward, with the exception of one man, who moved to Israel at the end of his life. A certain great Torah educator sought out that Jew, finding him in Holon, and asked him how he had managed to stay alive.

“When they opened the kever, everyone saw that the Gaon’s body was miraculously still whole,” the man related. “As soon as I saw the tip of his beard, with every one of its hairs still stiff as a needle, I turned my head and did not look at his face. The others could not contain their curiosity and looked at him.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 536)

Oops! We could not locate your form.