Rambam Illuminated

A long-ago art form sheds light on Maimonides and the medieval Jewish world where he flourished

Photos: Elchanan Kotler

T

he gallery walls are black, and the lighting is dim. But inside the display cases, it’s all light: glistening golds, vibrant reds, and shimmering blues. And while the stars of the show are the magnificent examples of medieval illuminated art, they don’t overshadow the real gems, the words of Torah that flow across the pages — the life’s work of one of the Jewish People’s most outstanding leaders: Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, more commonly known as the Rambam.

“Maimonides: A Legacy in Script,” an exhibition presented by the Israel Museum in partnership with the National Library of Israel, is drawing record crowds, according to chief curator Daisy Raccah-Djivre. To be precise, attendance in the museum’s Jewish Art and Life Wing is up by 60 percent. Considering that it’s not a special anniversary year for the Rambam, who was born in Cordoba, Spain, in 1135 (or 1138, according to some) and passed away in Fustat, Egypt, in 1204, why all the excitement?

Curator Anna Nizza Caplan, who along with associate curator Miki Joelson gave journalists a private tour of the exhibition, sums it up succinctly: “You’re going to see things at this exhibition that you will probably never see together again in Jerusalem or any other place.”

On the Road

“From Moshe to Moshe, there arose none like Moshe,” reads the famous epitaph on the Rambam’s headstone in Teveria. While the Rambam couldn’t trace his lineage back to Moshe Rabbeinu, he was descended from Jewish royalty: His family members were direct descendants of Yehudah HaNasi, the compiler of the Mishnah.

His father, Rabbi Maimon, was dayan of Cordoba’s beis din during a turbulent time in the city’s history. During the 10th and 11th centuries, Cordoba was one of the most advanced cities in the world, with a prosperous economy and more than 80 libraries and institutions of learning. But after the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in 1031, a century before the Rambam’s birth, the city was beset by sieges and power struggles. In the end, the city, as well as the rest of Muslim Spain, was conquered by the Almoravids and then the Almohads, two fanatical Muslim dynasties from North Africa.

The Almohadian regime gave the Jews a chilling choice: convert to Islam, be put to death, or go into exile. Rabbi Maimon, like many of Cordoba’s Jews, chose exile. For the next 12 years, the family wandered from place to place. Even though the Rambam lacked a stable environment during what we would call today his teenage years, the years of wandering didn’t have a negative impact on his learning. On the contrary, he began to write his commentary on the Mishnah when he was just 23 and while he was still on the road.

In 1160, the family settled in Fez, Morocco. But it turned out to be only a temporary haven from persecution. After further travels, including a brief sojourn in Eretz Yisrael, the family moved to Egypt and settled in Fustat, the Old City of Cairo.

Egypt’s Fatimid caliphs granted religious and civil freedom to the Jews living under their rule. But what should have been a period of tranquility was marred by personal tragedy. Just a few months after the family arrived in Fustat, Rabbi Maimon passed away. Several years later, the Rambam’s younger brother David, a dealer of diamonds and precious stones who had been supporting the entire family, drowned at sea.

The family’s entire fortune was lost as well, and the burden of supporting his and David’s family fell upon the Rambam. By this time, the Rambam was already regarded as one of the outstanding Torah scholars of his generation. But because he didn’t want to derive economic benefit from his Torah knowledge, he began to practice medicine instead.

This didn’t mean, though, that the Rambam curtailed what had been until then a prolific writing career on various Torah topics. If anything, the traumatic experiences he and his family had gone through during their long years of exile convinced him of the Jewish world’s desperate need for clearly written seforim that would answer halachic questions and strengthen the people’s faith.

Accessible by his own hand

“I was working on this commentary under the most arduous conditions… as we were driven from place to place… while traveling by land or crossing the stormy sea.” —Commentary on the Mishnah

Thus concludes the Rambam’s first major work, his commentary on the Mishnah, which was completed in 1168. But for those of us visiting the exhibition, the commentary is the first stop on our journey — or, rather, first two stops, because there are two volumes on display, Moed and Kodshim. The volumes are written in Judeo-Arabic, Arabic with Hebrew letters.

“Most scholars agree this commentary is written in his own hand,” says Nizza Caplan. She adds that the Rambam wrote the commentary in the Arabic vernacular because he wanted the Jews of North Africa and Arab lands, who spoke mainly Arabic, to understand the language. “The Rambam had a vision that he wanted his halachic works to be made as accessible as possible.”

If so, the Rambam was born at the right time, because he could write his commentary in a format that was still relatively new for the Jews: the codex.

In antiquity, books were written on scrolls, such as our familiar Torah scroll. A scroll was fine for a relatively short work, but it was an awkward, bulky format for longer ones. During the first centuries of the Common Era, the codex — an early type of bound book which enabled a person to leaf through the pages — became popular. For some people, that is. Early Christians were among the first to embrace the new technology; the codex’s portability and ease of use made it the perfect medium for traveling missionaries to disseminate their message.

By around 300 CE even pagans were using codices for their books. Jews, however, were slow to adopt the new medium. Historians aren’t sure why, but they offer a guess: Because the codex was so strongly associated with Christian religious texts, the Jews wanted nothing to do with it. But by around 700 CE the scroll was a thing of the past in the non-Jewish world. Although the Jews continued to use the scroll for a sefer Torah and megillos, other Torah works were increasingly written as a codex.

The relatively late transition from scroll to codex is confirmed by the Rambam himself. In his Mishneh Torah, which we’ll be visiting next, he speaks about “an old Talmud on scrolls, such as were written before current times, about 500 years ago (Hilchos Malveh v’Loveh 15:2).” He therefore dates the transition to around 700 CE as well.

The volume of Moed on display at the Israel Museum is currently owned by the National Library of Israel. Kodshim is owned by Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries. According to Nizza Caplan, this is the first time in about 400 years that the two volumes have sat together in the same room.

The two volumes, which were written on paper, as opposed to the sturdier vellum or parchment that was used in later years, look extraordinarily fragile — and they are. The fact that some of our early seforim found their way into national and university libraries therefore had a positive side; it helped to preserve them from destruction.

“Why did we bring a volume from Oxford if we already have one in Jerusalem?” asks Nizza Caplan. She points to the display case for Kodshim, where a full-page ink drawing of the plan of the interior of the Beis Hamikdash is on view. Perhaps there have been prettier illustrations done in the centuries since then, but the thought that this drawing — that served as a source for similar illustrations that appeared in later copies of the commentary and the subsequent Mishneh Torah — was penned by the Rambam’s own hand is, in a word, wow!

Clear and Concise for a Suffering People

At this time, the sufferings of our people have increased. The pressing need of the moment supersedes every other consideration. … Therefore, I girded my loins — I, Moshe, the son of Maimon, of Spain. I relied upon the Almighty, blessed be He. I… sought to compose [a work]… all in clear and concise terms, so that the entire Oral Law could be organized in each person’s mouth without questions or objections.” — Mishneh Torah, Introduction

Mishneh Torah was completed in the late 1170s. While the Rambam’s commentary followed the order of the Six Orders of the Mishnah, Mishneh Torah was organized into 14 books, an organization that he hoped would make the material clearer. It was also written in Hebrew, so that any Jewish community could understand it.

The first copy on display, which consists of Sefer Madda (Book of Knowledge) and Sefer Ahavah (Book of Love for Hashem), dates from the 1170s. The scribe was Yaphet ben Shlomo Haparnas. The accuracy of his work was verified by the Rambam himself, who wrote, “It has been corrected from my own book. I am Moshe son of Rabbi Maimon, the Righteous, of Blessed Memory.”

This authentic signature of the Rambam makes this manuscript very rare and valuable. The other copies on display, dating from later time periods and different countries, are unique as well.

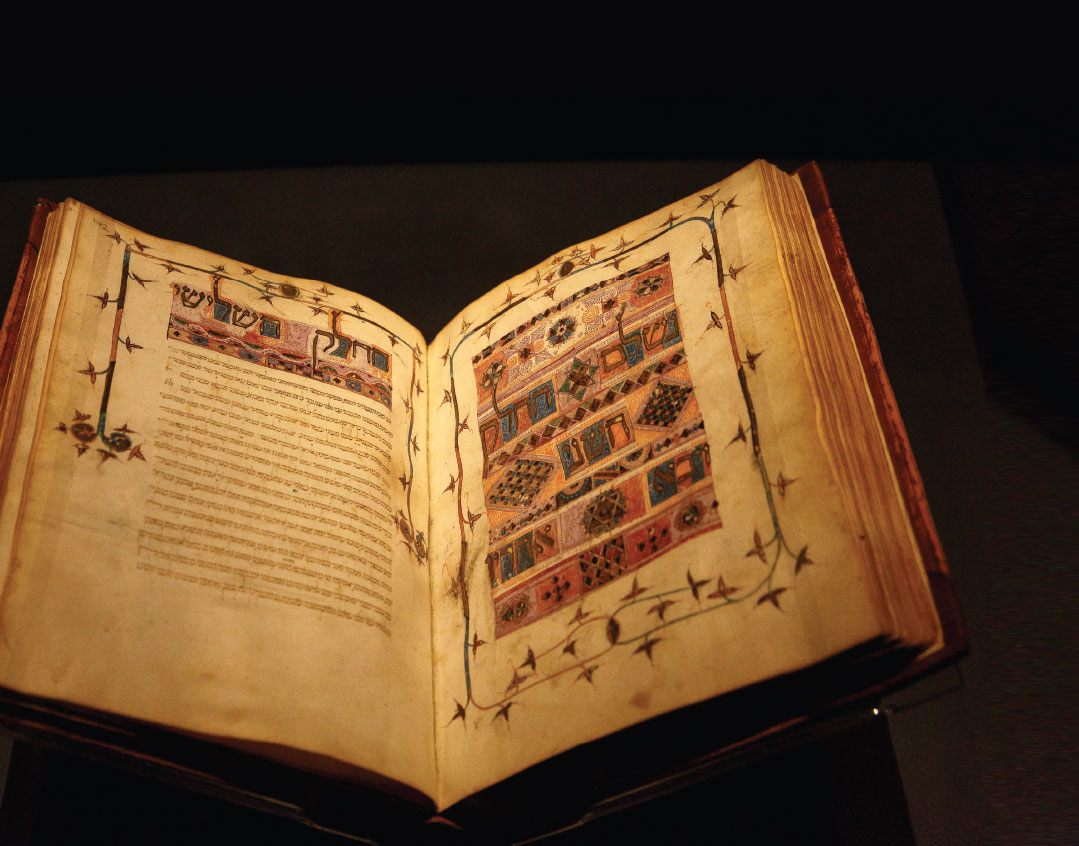

For instance, the Kaufmann Mishneh Torah, which was completed in 1296 in northeastern France by the scribe Nosson ben Rabbi Shimon Halevi, is an early example of an illuminated manuscript of one of the Rambam’s works.

An “illuminated manuscript,” according to a strict definition, is a manuscript where the text has been supplemented and “lit up” with gold or silver ornamentation. The term more commonly refers to any manuscript that has been embellished with elaborate and colorful designs and/or miniature paintings. It’s thought that there were illuminated scrolls in the ancient world, but illumination truly flourished as an art form only after the codex became popular.

Hebrew illuminated manuscripts, which began to appear in the 10th century in Middle Eastern Jewish communities and the 13th century in European ones, were expensive to produce. Therefore, illumination was usually reserved for the most important religious texts: Tanach, a siddur or machzor, a sefer Tehillim, and a Haggadah shel Pesach. According to Nizza Caplan, the fact that the Rambam’s works were also illuminated shows the high esteem in which he was held throughout the medieval Jewish world.

Kosher by Design

I lluminating a Hebrew text for a Jewish client was not without its challenges. For one thing, the fact that there is no capitalization of Hebrew letters deprived artists of one of their chief motifs: making an elaborate design out of the first letter of the first word of a book or chapter. Artists compensated by creating a design for an entire first word.

An even greater challenge was making sure the illustrations were kosher. In Europe, illumination was at first done only by monks living in monasteries, which is perhaps one reason why there aren’t any early European Hebrew illuminated manuscripts in existence; it’s hard to imagine a medieval Jew walking into a monastery and asking the monks to make some illustrations for him. (Although there is a theory that there were such manuscripts, perhaps painted by Jewish artists, only they have been lost.)

Secular workshops began to appear during the 13th century — Paris was an important center for this kind of artwork — and this is when Hebrew illuminated manuscripts began to make an appearance in Europe. But the artists were still mainly Christian.

“Because Jews weren’t allowed to be part of the artists’ guild, there weren’t many Jewish illuminators,” Nizza Caplan explains. “But a Jewish owner or the scribe could be involved in the choice of the illustrations.”

This usually meant that the Jewish patron or scribe would go to one of these secular workshops with his manuscript — the layout of the text had been designed to leave room for the artwork — and discuss the art: yes to a nice picture of Moshe Rabbeinu, but no halos, please, etc.

Usually, it worked out. But the Kaufmann Mishneh Torah is a good example of what happened when there was a miscommunication. At the bottom of the page there is an illustration of Moshe Rabbeinu standing on Har Sinai, receiving the two Luchos. Or is he? Art historian Evelyn M. Cohen spotted something funny about the picture back in 1985. When you look closely at the mountain, you see there are three hands grasping the Luchos and there are faces staring out of the mountain at Moshe.

What’s going on? Cohen surmises that the Christian artist at first drew the scene as he always did for his Christian patrons; he showed the arm of Hashem reaching down from the heavens to give the Luchos to Moshe. After the Jewish patron or scribe explained that Jews don’t depict Hashem in their artwork, the artist had to make a few corrections. Thus, we have a rather bizarre depiction of Moshe showing the Luchos to Am Yisrael, who seem to be standing inside the mountain. But that extra hand is still there.

Picture This

When I ask Nizza Caplan to name her favorite manuscript, she hesitates. “It’s like saying who is your favorite child,” she replies. But then she admits, “I think the Mishneh Torah from Northern Italy, circa 1457, is a masterpiece. The high quality of the illustrations — the shining of the gold leaf, the colors — is amazing.”

Created after the invention of the printing press, this Mishneh Torah is one of the last copies that were produced manually. Nizza Caplan explains that Volume I of this remarkable manuscript is owned by the Vatican Library, while Volume II was jointly acquired by the Israel Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few years ago. “It’s the most comprehensively illustrated manuscript of Mishneh Torah known to us,” she comments.

The page on display at the museum is the opening page of Nezikim (Damages). The artist has given us three illustrations for the topic: on top, an ox is goring a man; on the left a man is breaking into a house, while two men are having an angry dispute. If the illustration looks brand new, it’s thanks to the Paper Conservation Laboratory at the Israel Museum, which gave the volume a complete restoration a few years ago.

A close second, says Nizza Caplan, is an earlier Mishneh Torah, which was illuminated in Perugia around the year 1400. Only the first 40 leaves were decorated, but she comments that the quality of the artwork is outstanding. The manuscript also shows a new development in the history of these illuminations. Whereas early illuminated manuscripts featured scenes from Tanach that often had nothing to do with the accompanying text — they were for decoration only — by the 1400s there was more of an effort to match the picture to the text. Thus, at the bottom of the page where Sefer Ahavah begins, where there is a discussion of the halachos concerning saying the Shema, we see a man sitting on his bed, presumably saying the bedtime Shema.

Guides for the Body and Soul

The Rambam, who was the most prominent Jewish physician of the medieval world, became the personal physician of the Sultan’s court. He describes his onerous duties in a famous letter to one of his main translators, Shmuel ibn Tibbon:

My duties to the Sultan are very heavy. I am obliged to visit him every day, early in the morning, and when he or any of his children or concubines are indisposed, I cannot leave Cairo but must stay during most of the day in the palace. … I do not return to Fustat until the afternoon. Then I am famished but I find the antechambers filled with people, both Jews and Gentiles, nobles and common people, judges and policemen, friends and enemies — a mixed multitude who await the time of my return. … When night falls, I am so exhausted that I can hardly speak.

The letter concludes with a description of a typical Shabbos:

On Shabbat, the whole congregation, or at least the majority, comes to my house after morning services … We learn together a little until the afternoon, when they depart. Some of them come back and I teach more deeply between the afternoon and evening prayers.

Despite the grueling schedule, the Rambam continued to find time to write. The museum exhibition includes a Miscellany of Medical Texts — the Rambam’s summaries of essays written by second-century Greek-Roman physician Galen of Pergamon — which was probably produced in 14th-century Barcelona. The fact that even his medical works were illuminated shows once again how highly esteemed the Rambam was by Jews all over the world.

Moreh Nevuchim (Guide for the Perplexed), written around 1190, is considered the most important work of Jewish philosophy from the Middle Ages. It was also highly controversial. But even as debate about the Rambam raged across Europe, his seforim continued to be studied — and illuminated. On display is a copy from 14th-century Barcelona, which has Shmuel ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew translation from the original Arabic; its owner, Menachem Betzalel, must have felt an especial affinity for the Rambam’s works, because he too was a physician in the service of a royal court, the Catalan King Pedro IV.

End Pages

The exhibition concludes with a Moreh Nevuchim from 15th-century Yemen, which was written in Judeo-Arabic. Yemenite Jews had considered the Rambam to be their rabbi ever since he sent them the famous Iggeret Teiman (Letter to Yemen), written in the 1170s. The letter was a source of strength and consolation for the beleaguered community.

It has been a long journey for these manuscripts, most of which have changed hands many times during the centuries after they were written and illuminated. After this exhibition closes — it was scheduled to end on April 28, but it has been extended until June 10 — the manuscripts will be returned to their respective libraries. There they will be put back into storage, where the temperature and humidity will be monitored. A stable climate is especially important for manuscripts written on parchment or vellum, because animal skins expand and contract when the humidity fluctuates and that can cause damage to the gold leaf and paint.

Although some libraries have digitalized their collections, the manuscripts themselves will be shown only to researchers and scholars. In this way, they will be preserved for future generations to study and enjoy.

“This really is a rare opportunity,” says Nizza Caplan, as we conclude our tour. For as she mentioned at the beginning, these 14 manuscripts, which have survived centuries of exile, war, and persecution, may never again be in the same room together — or so easily viewed by the ordinary Jew eager to experience a part of our shared history.

(Originally Featured in Mishpacha, Issue 755)

Oops! We could not locate your form.