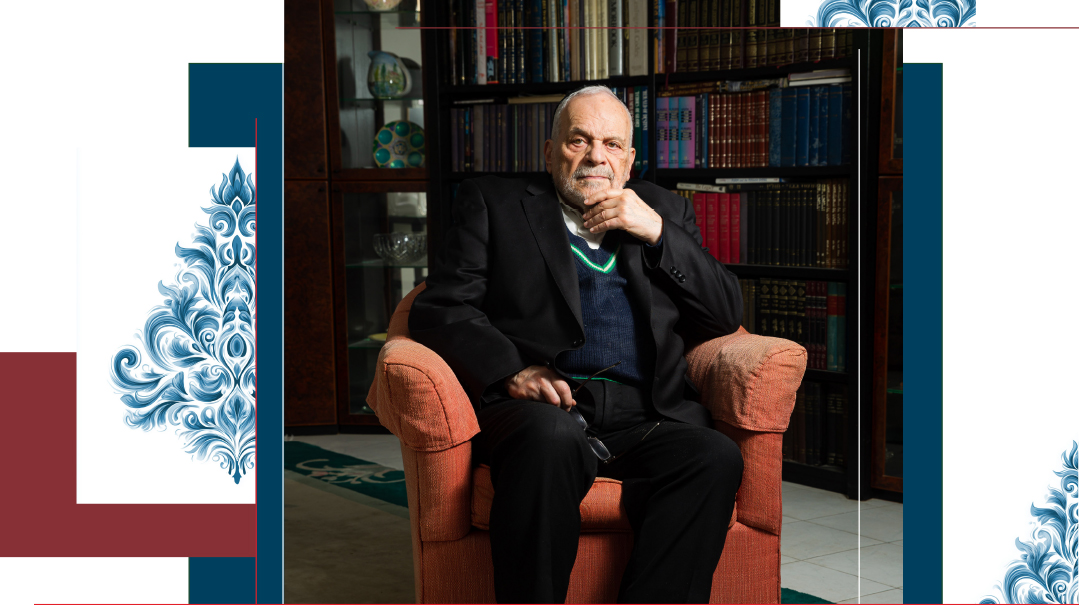

Purposeful Pen

| August 19, 2025This ability to get through to audiences through rhetorical power is a critical component of Rabbi Wein’s legacy

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mishpacha and family archives

IN the summer of 2024, as Hurricane Beryl carved its destructive path through the American South, another force of nature — gentler but no less formidable — was being celebrated in Jerusalem. Rabbi Berel Wein’s 90th birthday drew an elaborate five-and-a-half-hour marathon of tributes from across the globe, a testament to the countless lives he had touched through nine decades of extraordinary service to the Jewish people. Yet amid the outpouring of admiration and affection, perhaps only one person remained unmoved by the grand spectacle: the guest of honor himself.

Rising to address the assembled multitude, Rabbi Wein delivered a classic demonstration of the wit that had enchanted audiences for seven decades. With characteristic self-deprecation that caught everyone off guard, he opened with perfect timing: “I would like to thank the National Weather Service for naming a hurricane after me.” When the waves of laughter finally subsided, he added with prophetic prescience, “I am glad I can hear all of these eulogies while I am still vertical.”

This ability to get through to audiences through rhetorical power is a critical component of Rabbi Wein’s legacy. Each year, my wife and I would make our pilgrimage to hear his Shabbos Hagadol and Shabbos Shuvah derashos, a tradition he maintained with unwavering consistency for 71 consecutive years.

In the filled-to-capacity shul, I would invariably be awarded a seat right up front. People assumed that this was a tribute to my close connection to Rabbi Wein, which was no secret. I always quoted him, and on a few occasions, he even quoted me. Not only would I attend his lectures for nearly three decades, but when I had a delicate matter to discuss, particularly when I wished the counsel of an open-minded scholar, he was my go-to. The last two books that I wrote were honored by having, as Rabbi Wein referred to it, a “Discussion” about the book in front of capacity-filled Beit Knesset Hanasi.

And now for the truth. I sat up front because my good friend Dr. Ronny Wachtel, past president of Beit Knesset HaNasi, arranged a seat for me next to him (up front). Sitting in that hushed sanctuary on these very special rabbinic occasions, I would experience the mystical sensation of being addressed by an ancient prophet. When he would invariably insert his signature jest, delivered with bone-dry humor that ambushed you with its unexpectedness, the congregation would erupt in cascades of laughter.

Like a master craftsman who adorns himself with the instruments of his calling, Rabbi Wein wore many distinguished hats throughout his remarkable sojourn on earth.

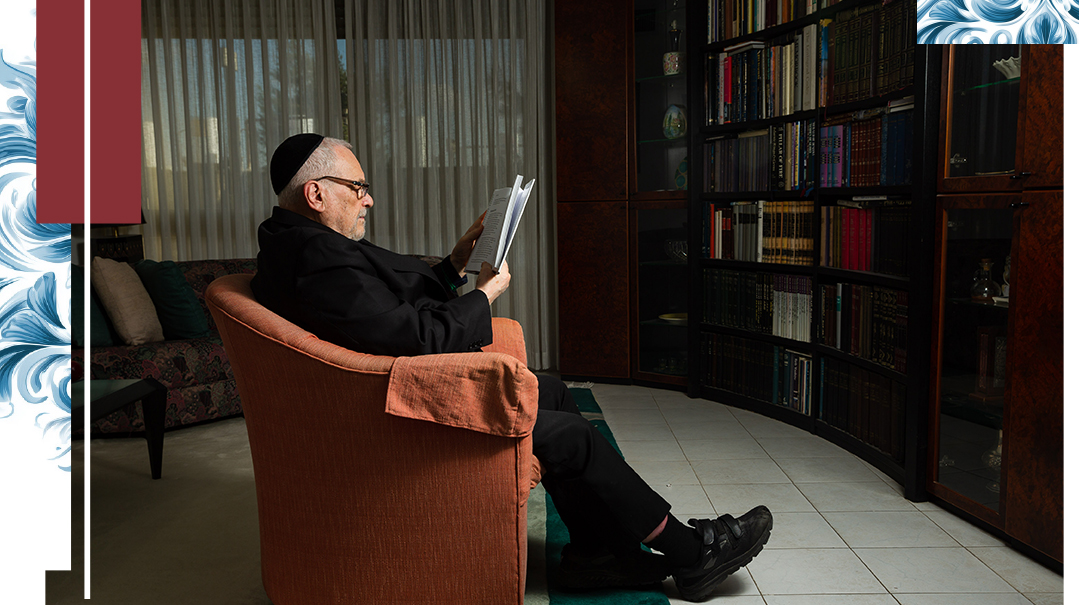

But the hat by which he was most recognized by the broadest swaths of the Jewish People was that of historian. His lectures and writings made the past come alive with a vigor that elephant stomped the high school stereotype of a historian. He possessed a preternatural ability to forge luminous connections between ancient chronicles and contemporary urgencies.

Akin to what is told about the Baal Shem Tov, whose mere recounting of sacred narratives could transport listeners beyond mundane boundaries, Rabbi Wein possessed the rare gift of making the past present, the distant intimate. This profound connection to Jewish continuity fueled his passionate love for the Land of Israel. For Rabbi Wein, the fulfillment of Jewish destiny was inexorably linked to the Land, and his fervent hope was that all Jews would recognize and realize their vital role in its ongoing story.

Rabbi Wein’s breadth of knowledge was astonishing. His friend Alfred Birnbaum recounted to me how he had taken Rabbi Wein to a naval museum in London. For every esoteric bust they passed, Rabbi Wein held forth on the admirals’ accomplishments in battle. When they returned home, Rabbi Wein excused himself and when he emerged less than half an hour later, he had written a full column for some periodical incorporating what he had gleaned from the naval museum.

His history lectures at Ohr Somayach (which I attended regularly) were delivered without notes, or even a momentary closing of eyes to access distant details. Once he mentioned something about American POWs in Japan which prompted me to present him with a weighty volume on the subject. I sheepishly apologized that the book’s considerable heft might prove burdensome given his demanding schedule, but instead his eyes lit up with unmistakable relish: “The bigger the better!”

His formative years in 1940s Chicago, where he developed perhaps the most authentically resonant Chicago accent ever to grace human speech — to the point people sometimes questioned where he was from — were spent under the tutelage of Lithuanian rabbis who possessed neither facility in English nor students who could navigate Yiddish. Yet somehow, through the mysterious alchemy of shared purpose and devotion, understanding flowed between teacher and pupil. This was, as Rabbi Wein would later characterize it, the Golden Age of the “Skokie Yeshiiive” (as true Chicagoans pronounce it).

I do not recall a single talk where he did not invoke the wisdom of these early mentors, including the Satmar Rav, and I believe his favorite, the Ponevezher Rav.

Rabbi Wein once shared how his classmates would tuck newspapers beneath their Gemaras, and how Rav Mendel Kaplan, rather than censure, seized upon it as pedagogic opportunity. “Boys” (or probably, boychikels), “let me show you how a ben Torah reads a newspaper.” What followed was a masterful demonstration of interpreting headlines through Torah wisdom.

When I was menachem avel Rabbi Wein over the passing of his father, he related that Rabbi Zev Wein, who was desperate for employment, was offered to be the rabbi in what was known as a “traditional synagogue” that was common in Chicago at the time. These were Orthodox synagogues where the men and women sat separately, but were mechitzah-less. Many a learned, God-fearing rabbi served in these posts.

Rabbi Wein’s father did not wish to cast aspersions upon the rabbis in town that occupied such posts, but he demurred the opportunity by stating simply, “I saw Reb Shimon (Shkop, rosh yeshivah of Grodno) and therefore I am unable.” Just seeing a scholar of this caliber had indelibly shaped his conception of acceptable compromise.

Whether unveiling novel interpretations of Rambam or offering fresh Talmudic perspectives, his presentations were invariably seasoned with historical and contemporary references that only his vast erudition could supply. In this year’s Shabbos Hagadol derashah address, delivered after Hassan Nasrallah’s assassination, Rabbi Wein related that he heard the recording of the commander of the IAF to the pilot who reported the success of his mission (where in the world did Rabbi Wein always have access to these obscure sources?). “Yasher koach,” not the parlance, commented Rabbi Wein, usually associated with the Israeli military.

In his “Words of Praise” for my “Hey Taxi!” (1991), Rabbi Wein described the stories within as warm, engaging, and “morally purposeful.” I am unaware if those two words have ever been paired together before, nor have I come across such a conjunction elsewhere. Yet, ever since he implanted that succinct, powerful phrase within me, it has served as the mission statement for my writing, encapsulating what Rabbi Wein taught every day of his life.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1075)

Oops! We could not locate your form.