Purim Edition: Readers’ Mailbag

| March 19, 2024Purim gives our readers a chance to unload their questions, concerns, and commentary

Shtetl Shabbos Takeout?

Dear Dovi & Yehuda,

As a mother navigating the aisles of my local kosher grocery store, I find myself increasingly dismayed by the soaring prices. I’m turning to you, as historians of the prewar era, because I’m curious to learn how frum families dealt with similar issues back then.

My readings have immersed me in their struggles with parnassah, shidduchim, and occasional shul politics, revealing that our challenges haven’t changed much over the years. Yet it strikes me that people in these historical accounts rarely lament the cost of everyday necessities, such as spare ribs, parmesan cheese, or simple Shabbos takeout (the thought of which evokes cravings for authentic Hungarian delis of the past.)

Can you enlighten me on the strategies they employed to mitigate their financial burdens, and possibly suggest how we might apply those lessons today? I find myself exasperated and disheartened every time I tally a grocery bill.

Sincerely,

Mindy from Monsey

Dear Mindy,

Thank you for sending such an interesting question. It’s plausible that our ancestors were too busy with dawn-till-dusk endeavors like drawing water, milking cows, and plucking feathers, to have time to air grocery grievances.

Furthermore, the absence of forums such as the Agudah Convention, frum websites, or ubiquitous WhatsApp groups meant that their culinary conundrums were confined to kitchen walls rather than broadcast for communal commiseration.

Dovi & Yehuda

How Many “Last Boats”?

Dear esteemed historians Dovi Safier & Yehuda Geberer,

I recently had the pleasure of reading your enlightening article on Rav Yitzchak Alkalai of Yugoslavia. His remarkable escape from Nazi clutches, through Bulgaria to Istanbul, Turkey, before finally reaching Palestine, and eventually America, resonated with me. This narrative strongly resembles my own family’s lore, specifically the daring escape undertaken by my grandfather from Europe during that tumultuous period.

According to stories passed down through generations, my grandfather managed to secure passage on what was often described as “the last boat” leaving Europe for the safety of the United States. This account, cherished and retold at family gatherings, has always been a source of pride and a testament to my grandfather’s resilience. However, your article has sparked my curiosity about the intricate details of these escapes and the routes taken by those fleeing persecution.

My grandfather’s journey did not take him through Turkey. His getaway originated from France, making me wonder about the timing and nature of these voyages. Did Rav Alkalai board a later vessel, meaning that my grandfather’s ship was not, in fact, the last one to leave Europe? Or is it possible that my grandfather’s passage to the United States occurred on a boat that departed later than others?

This conundrum has led me to ponder the broader phenomenon of Jews escaping Europe during the Holocaust via “the last boat.” The term itself seems to have become a symbol of hope and miraculous survival against all odds. Yet the historian in me can’t help but question: How many of these “last boats” were there? Given the numerous accounts and the variety of escape routes mentioned, could it be that there was some sort of flotilla?

Thank you once again for your compelling work and for inspiring this inquiry into my family’s past.

Warm regards,

Milton Schwartz

A Bone to Pick with Bonaparte

Dear Esteemed Historians,

I’ve been scratching my head about something, and I think you’re just the folks to help me figure it out. I’ve been a big history buff since around third grade. I’ve listened to almost everything out there, from cassettes by Rabbi Wein and Rebbe Hill to Jewish History Soundbites and the wonderful Jewish History podcasts that Mishpacha puts out. I’ve hardly forgotten a story.

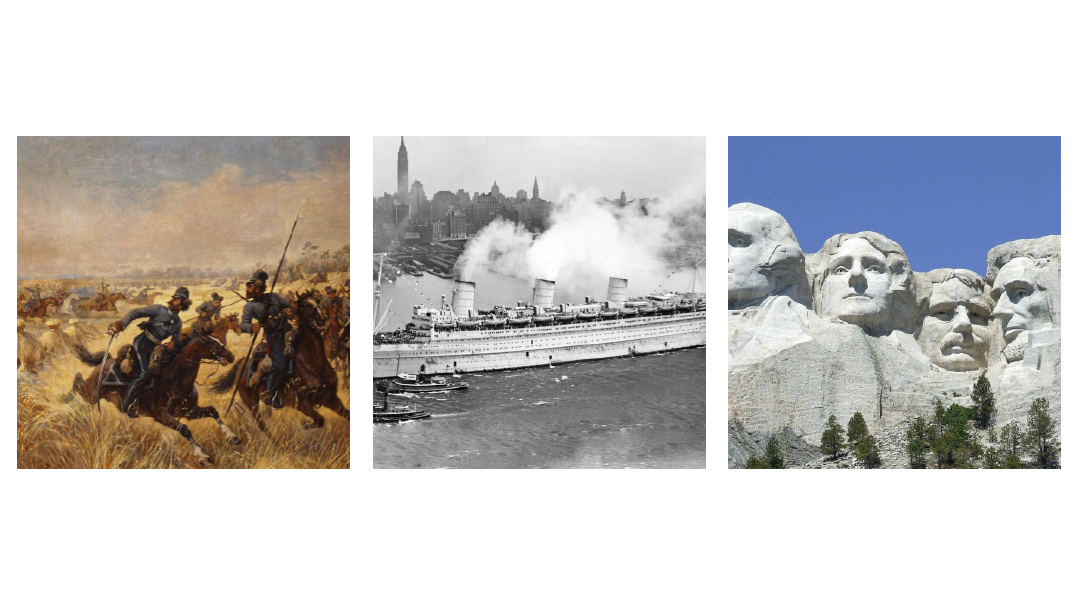

If there is one character in history who confuses me, it’s Napoleon Bonaparte. He is surely on the Mount Rushmore of military geniuses, along with 20th-century generals like Patton, Montgomery, Schwarzkopf, and of course, General Mills (ha-ha). As the emperor of France, he was surely a busy person as well.

But according to the stories I’ve heard, it seems that he visited gedolim at a rate eclipsed only by an American yeshivah bochur during his first bein hazmanim in Brisk. During the course of just a few months, he is said to have met with Rav Nachman of Breslov, Rav Simcha Bunim of Peshis’cha, the Maggid of Kozhnitz, and of course, Rav Chaim Volozhiner. Got me thinking — how’d he manage all those visits with gedolim if he was so busy fighting wars?

Now, these are far from my only questions. We know that Napoleon didn’t speak Yiddish, and I’m assuming that the gedolim of the time did not speak French. Who interpreted for them during those meetings? Did any of these translators ever go public with their stories? Also, if these meetings actually occurred, where are the “pictures”? We know that there are entire museums in Europe filled with depictions of Napoleon. Is it possible that among the thousands, there isn’t one painting of him meeting one of the aforementioned gedolim?

Please help!

Shlomo

Dear Shlomo,

Excellent question, though we’re not sure we’re the right address. As fans of For the Record are aware, our knowledge of the time period from Churban Bayis Sheini to around 1854, when the Netziv became rosh yeshivah in Volozhin, is fairly limited.

Speaking of the Netziv, though, there are a few tidbits we have picked up here and there from the years preceding his ascent. You might not be surprised to hear that many of them involve the Netziv’s hometown of Mir.

The Battle of Mir took place on July 9 and 10, 1812, during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. Three Polish cavalry divisions valiantly fought Cossacks under the command of General Matvei Platov, though the battle ended with the first major Russian victory in the war. The Mir Castle served as the military headquarters for Napoleon’s brother, General Jérôme Bonaparte, a much-maligned commander in the Grande Armée. Jérôme was ordered back home by his brother following the crucial loss and relieved of his duties.

It’s unclear to us whether Jérôme Bonaparte ever met the Netziv’s father, Reb Yaakov Berlin, though it is entirely plausible that the Netziv grew up playing in the ruins of Mir Castle, which was destroyed following the battle, and later rebuilt by the town’s poritz.

Best regards,

Mishpacha’s modern (era) historians

P.S. Of course, we don’t generally go off-topic too often, but since we mentioned Jérôme Bonaparte, we should relate that his grandson, Charles Joseph Bonaparte, served as US Secretary of the Navy and US Attorney General in President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration from 1901 to 1909.

Perhaps most notably, in 1908 Bonaparte established a Bureau of Investigation within the 38-year-old Department of Justice. In 1935, it was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under legendary director J. Edgar Hoover.

Pop Your Diaspora Bubble

Dear Editor:

In the recent For the Record column titled “Mussar Travels,” the authors write, “Rav Chatzkel was the first mashgiach at the newly reestablished Mirrer Yeshivah in Brooklyn, until his immigration in 1949 to Israel, where he was employed by Mir Yerushalayim.”

Now, hold on a minute. One doesn’t simply “immigrate” to Israel. The correct term, infused with the spiritual elevation of the act, is aliyah. This subtle nod to an American readership, cozy in their diaspora bubble, strikes an odd note for a frum publication.

Wherever Safier and Geberer find themselves — be it the historical yeshivah havens of Vilna, Minsk, or Pinsk — it’s high time they recognize that the Promised Land is calling. Gone are the days when one needs to schlep Diet Dr. Pepper and Snapple 5,000 miles to feel like he is in galus. All of that can be obtained here.

The same goes with popular “American” snacks like Doritos and Bamba. Just don’t ask for that ice cream brand born in Vermont! The rabbanim here banned it following the historic “Beit Shemesh Ben & Jerry’s Asifah” in 2021.

Oh, and if parnassah remains a concern, my husband (as well as most of his friends in our Beit Shemesh neighborhood) commute to the US, where apparently some Jews still reside for the time being.

So, to our dear columnists, and anyone else still on the fence, it’s time to pack up those seforim, say goodbye to the land of Trump and Biden, and join us in the land of milk, honey, and endless elections.

A Bubby in Beit Shemesh

Green with Envy

Dear Authors,

I write to you from the holy city of Yerushalayim, where I am currently attending Machon Bais Binyomin Seminary for Aspiring Educators and Moros (MBBSAE&M, or as we affectionately dub it, “Machon Beis Schlep”). After devouring your recent piece on Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, my feelings oscillated faster than my roommate trying to decide if she was in the mood for café-salmon or saving-money-tuna. The life of a bochur at Chachmei Lublin, where both ruchniyus and gashmiyus were five-star, left me green with envy.

Here I am, a full century after Rav Meir Shapiro broke ground, cramped in a dorm room with five other girls. Meanwhile, the Chachmei Lublin bochurim (for $25,000 a year less!) were living the high life with spacious dorm rooms, personal laundry services, and delectable dining facilities that make our seminary’s fleishig-milchig kitchenette look like a shtetl soup kitchen.

Our current “luxuries” include navigating laundry machines that swallow our five-shekel coins, and engaging in the sacred art of Betty Crocker cookery — albeit in a country where Kind bars cannot be found.

I’m not going to gloss over the specifics, but a library with 100,000 seforim? Beautiful gardens to roam around and study in? Meanwhile, our crowning glory is a “rooftop lounge,” which quite frankly is just the unfinished shell of the fourth floor of our building. While the cats that live up there seem to be nice, even I wonder how they survive in those conditions.

I know I should be grateful for the opportunity to spend a year in Eretz Yisrael, surrounded by like-minded young women who share my passion for serving Hashem. But really, would it kill them to install working washing machines and dryers? And forget being served by waiters on fine china; maybe someone could think about serving us actual Shabbos meals that don’t consist of oily soup and hummus and challah? I know the teg system worked for some, but even the litvishe yeshivos got rid of it by 1930!

Yet as I look around at my fellow aspiring students, all of us united in our quest for growth amid the trials and tribulations of seminary life, I realize perhaps Sarah Schenirer herself would chuckle at our predicament. After all, isn’t the true essence of a Bais Yaakov girl the ability to find joy and purpose, even when the hot water runs cold, and the bus to the Kosel takes 90 minutes?

Enviously,

L.M.

MBBESAE&M Class of 5784

P.S. Can you please find me some proof to show to my mechaneches that the Bais Yaakov in Krakow was nicer than our seminary????

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1004)

Oops! We could not locate your form.