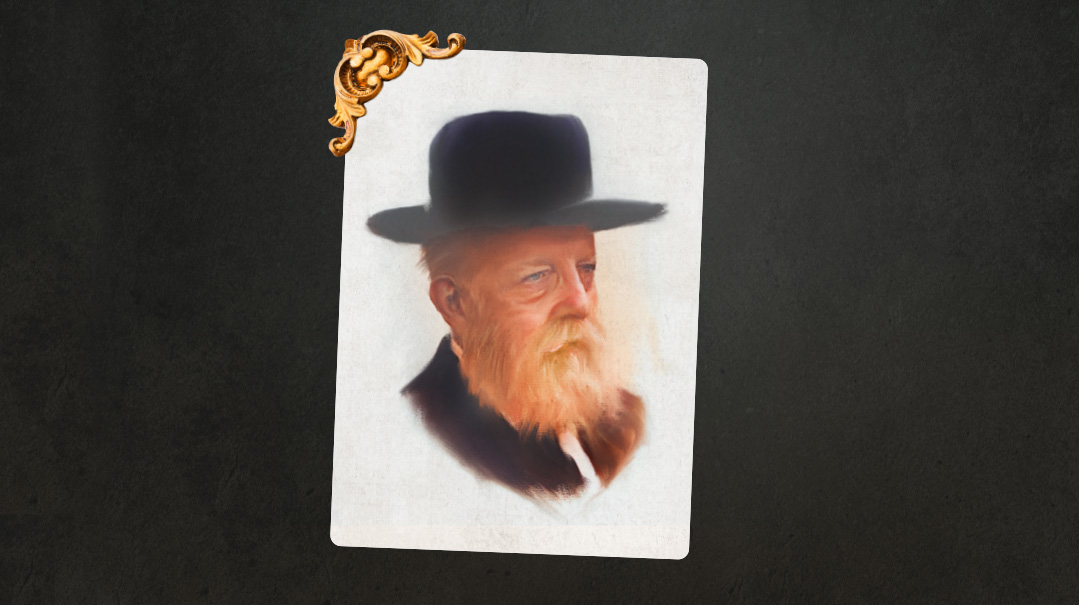

Prince Without a Crown

| August 27, 2024Reb Shlomenyu of Sadigura chose a different path, yet always remained a child of Ruzhin

They called him Reb Shlomenyu — a nickname that connotes simplicity, but actually conceals a complex and fascinating life story. In a way, the simplistic moniker was a fitting cover for an enigmatic individual who eschewed the rabbinic title that he’d inherited, a man who traveled in many circles and engaged in pursuits that defy easy categorization.

Who was Reb Shlomenyu of Sadigura? A revered rebbe to hundreds of followers, including those quadruple his age? An askan who traveled the world searching for Jewish children raised in gentile homes? A fundraiser for the many causes he was involved with? A member of the Zionist Congress, or perhaps even a popular columnist for a religious Zionist publication?

The most accurate answer is probably, “All of the above.” And then some.

After extensive research on this enigmatic and remarkable figure, who passed away more than half a century ago on 26 Av 5732/1972, another question arises: Why was his life story never told? The answer is actually encapsulated in the very question. Although he gave up his official title as Rebbe, in appearance, he remained a chareidi Yid, and was recognized as a tzaddik by the rebbes of his time; he was seated alongside them on the dais at public events. His regular literary contributions to HaTzofeh, the popular Religious Zionist mouthpiece at the time, was definitely most unusual for people of his stature and background. Perhaps in an era of rampant polarization, Reb Shlomenyu’s story could not have been “adopted” by any political agenda or affiliation and he could not fit into a neat box of a specific “type,” and therefore, it just remained untold.

And so, the question remains: Who was this exceptional personality who gave up everything to devote himself to the klal — in the broadest sense of the term?

Regal Beginnings

It was 1917, just after World War I, and a chassidic figure stood outside the stately building in Vienna’s city center, holding a small, golden antique snuff box. Inside, a meeting was in progress to determine who would receive the special entry visas that the British Mandate issued sparingly to a handful of lucky Jews. As the offices were run by leftist Zionists, the chances of a religious Jew receiving one of those coveted visas was minimal, at best. Aware of this, the chassidic Yid had come down to the office to try to help frum individuals seeking to make aliyah.

An acquaintance spotted him outside the building and asked him what he was doing there.

“On the chance that I manage to convince the agency to grant a religious person a visa, there’s still the issue of paying for the trip, and I’m worried someone may not have the financial resources to purchase passage on a ship leaving for Eretz Yisrael,” the man explained. “I brought along this antique snuff box so that I can pawn it immediately if these olim need money.”

The snuffbox was no ordinary piece. It was an heirloom, inherited by one of Europe’s most revered chassidic rebbes. And the man who was prepared to give it up was no ordinary Jew either. He was Reb Shlomenyu of Sadigura, son of Rav Yisrael of Sadigura and great-grandson of Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin — although by that point in time, he was no longer a “practicing” rebbe, a choice that he alone made.

Oops! We could not locate your form.