While planning our itinerary to the jungles of Papua New Guinea to meet tribesmen who claimed a Jewish link, we learned that right across the border in Indonesia, there were also emerging communities desperate for Jewish contact.

W

hen we heard that members of the Gogodala tribe in Papua New Guinea claim descent from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel and are now expressing interest in returning to Judaism we just knew we needed to plan a trip to the South Pacific jungles and see them for ourselves. We wrote about that trip last month; yet while still in the planning stages of this newest halachic adventure we learned that on the same island but right across the border there were emerging Jewish communities in Indonesia the world’s most populous Muslim-majority country.

If that confuses you we can explain: The island of New Guinea has a border drawn right down the middle; the eastern side is Papua New Guinea (PNG) our original destination and the western side is Papua Indonesia. Indonesia a country which is actually a collection of over 17 000 islands straddles the equator and stretches over thousands of kilometers from the Indian to the Pacific Ocean. With over 260 million people it is the world’s fourth most populous nation. Although overwhelmingly Muslim (85 percent) it is officially secular and there is a sizable Christian population. Hinduism Buddhism and Confucianism are all recognized religions as well; Judaism is not.

In the last few years though different groups in Indonesia have begun to call themselves Jewish and have even opened synagogues. It was the community in Jayapura Papua Indonesia — just across the border from Papua New Guinea — that we decided to visit.

Border Blues

Our goal was to meet the members of Kehilat Yehudim Torat Chaim in Jayapura the provincial capital on the northern coast of the island on the Indonesian side. We went with no expectations and even contact with their leader Aharon Sharon was difficult as they speak little English.

Still all of this was facilitated by the “chief rabbi of Indonesia” the affable Rabbi Singer a well-known anti-missionary expert who has been living in the capital city of Jakarta — 4 000 kilometers away — for the past few years. He now heads a congregation of descendants of Jews who hid their Jewish identity for centuries (and he’s also become a popular speaker in local mosques). Joining us along with Rabbi Singer were our travel partner Rabbi Eliyahu Birnbaum and our new friend Tony Waisa leader of the Gogodala tribe which we had already visited deep in the jungles of Papua New Guinea.

Nothing is easy in that part of the world. We were coming from Port Moresby the capital of Papua New Guinea and needed to fly to Vanimo in the north of PNG and not far from the Indonesian border. After we got to the airport we were told our flight was delayed and ultimately canceled. Finding another flight was no simple matter (as we learned the previous week when a canceled flight meant we had to spend Shabbos in the jungle). We did finally find another flight but the two-prop plane acting like a delivery service made stops in Lae Madang and Wewak dropping off packages mail and about 500 baby chicks who were making quite a racket during the flight.

The small plane, landing on makeshift landing strips, cannot fly in the dark, but the pilot assured us we would make it before sunset. The view of the coastline and the endless pristine forests was beautiful, but it was taking hours and we were getting nervous because the border from Papua New Guinea into Indonesia officially closes at 4 p.m. Meanwhile, on the other side of the border, the entire community of Kehilat Yehudim Torat Chaim was set up for a grand meeting, and many had been waiting there for hours. One man later told us that he was so excited by our visit, which was the very first delegation from outside Indonesia to ever meet them, that he could not sleep all night and had been there since the morning.

In the end, our plane landed at 6 p.m., but we had an ace in the hole. We had been arrested in Papua New Guinea the day before for flying a drone, yet the military man who arrested us later softened and even became enamored with us — so much so that he offered to call his buddy who is “in charge of the border” to let us through despite the hour. (The protektziya felt great, and the group, led by Aharon Sharon, told us they too had arranged on their side of the border for us to come through after hours as well.)

We drove to the border on a pitch black night on a single-lane road with dense dark jungle encroaching on both sides, and narrow bridges crossing raging rivers all the way to the border. We could hear millions of bugs and an occasional animal call — a cacophony of nature at its best. And as planned, the military was prepared to let us through. The soldiers took our passport details, snapped some photos with us, and waved us through. We did a lot of laughing and backslapping, thinking that we had beaten the system. But when we got to the border gate itself — several miles from the military checkpoint — it was locked with not a soul in sight. We had never seen such a quiet border without even a sentry or guard tower. Turns out that the customs officers are the ones who open the gate, and even after tracking them down in their bungalow colony, no amount of wheedling would get them to open up before the morning.

Please Teach Us

We dejectedly returned to Vanimo, stayed in what could not have been more than a two-star motel, and returned to the border early in the morning. We were standing at the Papua New Guinea gate when the Indonesian side slid open at 8 a.m. Indonesia time (9 a.m. Papua New Guinea time!) and began to walk the quarter mile from the third world of Papua New Guinea to the customs house on the second-world Indonesian side — when suddenly cars pulled up with local Indonesians wearing black velvet yarmulkes and tzitzis. After an emotional “Shalom,” these men tearfully embraced us like we were their long-lost brothers. We had very limited time, as our flight to Jakarta was leaving later that afternoon, and so they took us directly to their shul, which is built abutting Aharon’s house.

What we found was so refreshing and unexpected it left us looking at each other in amazement: Here, on a remote island in the Pacific Ocean, was a group committed to Torah and mitzvos, and so very different from many of the communities we have visited over the years.

As our minivan turned off the main road, we saw people with Israeli flags, a large sign welcoming the “delegation from Israel,” and a tent holding maybe 50 people joyously singing, dancing, jumping, and hugging. “Hashem melech, Hashem malach, Hashem yimloch l’olam va’ed” rang out along with “hinei mah tov u’mah naim shevet achim gam yochad” as they placed flowered wreaths around our necks and pulled us into their circle. The men wore yarmulkes and the married women had their hair covered.

One of the many surprises of the day was meeting our translator, a frum young woman by the name of Elisheva Wiriaatmadja. Her father’s grandmother was Jewish, although she married a Muslim man and converted to Islam. But three generations later, Judaism beckoned and Elisheva desired to learn more about her lost heritage. Following a group Conservative conversion, she decided to become Torah observant, and both she and her sister were halachically converted by Rabbi Moshe Gutnik and his beis din in Sydney, Australia.

Elisheva was born in Indonesia, grew up in Germany where her father worked for the Ministry of Tourism, and then returned to Indonesia as an older teen. The town where she grew up, Pondok Gede, means “big house” and is named after the mansion of a Polish Jew who became a wealthy goldsmith there in the early 19th century. Elisheva is trained as an architect but no longer works in the field because no firm would permit her to observe Shabbos and Jewish holidays. Instead, she is the Jakarta representative of kosher certification organizations such as Kashrut Authority Australia and Singapore Kosher. And because she is fluent in Indonesian, English, and German (and learning Hebrew) she is often the translator and spokesperson for the community.

Haven across the World

While Jews arrived in these parts as early as the 1500s, few remnants of Jewish life and tradition remain. Jews made their way to the east during the era of Columbus and the age of exploration, which was largely about finding a quicker route to the Spice Islands — which are now the archipelago of Indonesia. In 1512 the Portuguese sought exclusive rights to these islands, which grew nutmeg, pepper corns, and cloves. It might be hard for us today to conceptualize the importance of these spices in world history — but wars were fought over them and world trade was dominated by them.

When the Dutch East India Company took control of the islands, the door opened for Dutch Jews to move where opportunity beckoned. The Netherlands had already been welcoming Jews chafing under the Inquisition, and they were joined on these travels by Jews from Baghdad and from the southern Yemenite port city of Aden who were also looking for opportunity.

In the 1850s, Jerusalem talmid chacham and explorer Yaakov Sapir described visiting Batavia — as Jakarta was then known — and meeting Jews who told him about the various small communities in Indonesia. He requested that the Dutch community send a rabbi to lead them. The community continued to grow, and by World War II there may have been as many as 2,000 Jews in the Dutch East Indies, i.e. Indonesia.

They fared poorly under the Japanese occupation of the islands — some of them dying in detention — and most left soon after the war. The community has dwindled, and the last freestanding shul, in Surabaya, was totally demolished by Muslims in 2013, despite being on a governmental list of protected buildings. There are still some intact Jewish cemeteries in the country. Recently the small Shaar Hashamayim shul has begun functioning in Tondano, a city on Sulawesi (formerly known as Celebes) island.

A variety of factors contributed to the almost complete assimilation of the few Jews that remained. Every Indonesian over the age of 17 must carry a government ID card called KTP (Kartu Tanda Penduduk) on which the individual’s religion is listed. Judaism is not a recognized option so most Jews listed Christianity. In 2013, the religious affairs ministry permitted people who do not follow one of the six recognized religions to leave the religion designation blank, but fear of attracting attention has led most people to still list one of the six. In addition, over the years they took on Indonesian names.

There are today in Indonesia approximately 100 descendants of Jews, who live mostly in Jakarta. Elisheva was one of them. About eight years ago, she felt the tug of Judaism and began educating herself, and in 2012 started writing a newsletter about Judaism. Today, she has about a thousand Indonesian subscribers from in-country and all over the world, who are slowly rejecting idolatry and becoming Noahides.

Forced to Hide

Elisheva’s subscribers considered her an authority on Judaism, inviting her to speak and teach them. One of those groups was Aharon Sharon’s community. Their remarkable story goes back to the days of the Inquisition — and much has remained hidden until today.

Aharon rose to speak, and with Elisheva’s translation, told us that his family were Anusim, forced to flee from the Inquisition. At times tears rolled down his cheeks as his tale unfolded, describing how his family was forced to give up their old customs. He said that their family ended up in Peru many generations ago. When the Spanish came to Peru 400 years ago, they were again forced to flee. Peru is on the western coast of South America, so the direction they fled was into the Pacific Ocean in the direction of Asia. The group’s ancestors put some of the young strong people, including one of Aharon’s ancestors, into boats in order that they, at least, should be spared. They were told to travel until they found the land with the “blue mountain.”

After two years they eventually arrived in Papua after a brief stay in Japan. Aharon pointed out a mountain to us whose rock has a bluish tint that they assume was the “blue mountain” which signaled to their ancestors that they had arrived. Interestingly, their story continues in the 1880s when missionaries arrived, burned their shuls, took their only Torah scroll, and forbade observing Shabbos on Saturday and other Jewish practices they still maintained.

In 1969 the government of Papua Indonesia required they choose a religion, and they chose Christianity because Judaism was not on the approved list. Aharon said that they were never comfortable with Christianity, and Judaism beckoned him back. His mother had always told him to get circumcised and to do the same to his sons.

Aharon Sharon explained to us that all his community in Jayapura wanted was for us to teach them some Torah. We talked about many topics, including the Shema and basic beliefs of Judaism. We talked about halachos of kashrus, Shabbos, shul construction, and prayer. They begged for kosher slaughter and so a handful of chickens were rounded up and shechted. We also left them with some books, including a set of Hebrew/English Chumash with Rashi, gave them a supply of kosher wine, and explained our interest in groups like theirs around the world. But mostly, we gave them chizuk to continue on their spiritual path.

Back to the Melamdim

When we meet a group that claims some Jewish descent or historical link, we always try to question them subtly, in order to tease out traces of Judaism that might truly show a historic connection. Sometimes it’s a family tradition like lighting candles on Friday. Another one is sweeping dirt to the center of the room as opposed to out the door, lest one denigrate the doorpost where a mezuzah should be. There are many other things that Anusim used to do as a secret connection to Judaism. At some point we asked for their story and Elisheva began to translate.

According to Aharon’s family tradition, the family name in Peru had been Carmen. We asked more about his forefathers and if there was a first name. His answer was possibly the most telling hint about the veracity of their tale. He reverentially said that they did not use the given names but rather called these leaders by a title. We were flabbergasted when he told us, “We have always called our elders melamdim.” This is a word that does not exist in the local language and most importantly, they had no idea that it meant “teachers” in Hebrew — they simply passed the word down from generation to generation.

Aharon is a descendant of the melamdim. His cousins, other descendants of these leaders, are still using this name as their surname until today. Interestingly, when Aharon’s family changed their name to the rare Japanese name Hokoyoku, some of them separated themselves and said that they did not want to have anything to do with any changes — they wanted to call themselves as their forefathers were called, and adopted the surname “Melamdim.” It is possible that the “Melamdim” clan is still keeping Jewish traditions, but contact with them is difficult, as they separated themselves to a place in Papua which is not easy to reach by land. Similarly, some of the families refer to G-d as “Hashem” without knowing why.

We wanted to find more Jewish connections to the past. When asked about any unusual customs his mother or grandmother had, Aharon answered that there was a lullaby they would sing to them as children, which included the words: “We were once twelve brothers but ten of them are now missing.” At a certain age the kids had a ritual of building a boat, which they would take out into the bay to commemorate their roots and symbolize their hope for return.

Time for Minchah We were totally absorbed in Aharon’s story when Elisheva, our translator, told us she needed to leave for half an hour. “You see,” she said, “we brought a traveling kosher kitchen, stove, pots and all, and I am going to make you a traditional Indonesian dinner of fish and rice.” Not having eaten a proper meal in close to two weeks, we were very happy about that announcement. In the meantime, we went into Aharon’s shul for Minchah. Aharon’s community — which is not halachically Jewish — has a shul attached to his house, which holds three services a day. It was clear that they knew the davening and the proper responses. We were privileged to join them for Minchah the day we were there.

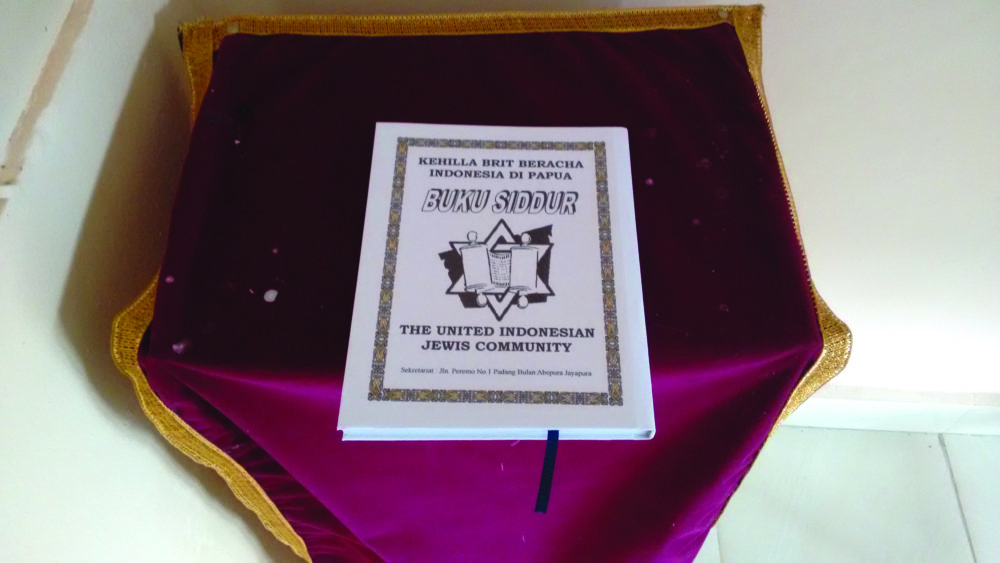

It is a proper shul in every way, although the aron kodesh holds a Chumash instead of a sefer Torah. They’ve even translated their own siddurim into Indonesian. Like many of these very remote communities, any item of Jewish connection becomes important and these items are proudly displayed in the bookcase in the front of the shul — which hold some candlesticks and other silver items, some books, and two boxes of matzah. We were exceptionally moved by their devotion, mesirus nefesh, thirst for knowledge, and hope for the future.

One man, who spoke a bit of English, something the elders did not, told us his name was Elisha and that he wants to become a rabbi. So here is our question: How can we help the Jayapura community? True, they are not halachically Jewish, but unlike many communities we have encountered, they are small, centralized, essentially one big extended family with a passionate leader. Most importantly, all of the members, including the younger generation, want to learn and fulfill the Torah and most definitely want to convert according to halachah. They are wont to quote Isaiah 43:6: “I will say to the north, ‘Give up’, and to the south, ‘Keep not back: Bring my sons from afar, and my daughters from the ends of the earth,’ ” as applying to them. And they even viewed our visit, which was featured in a local paper the next day, as a continuation of this historic process.

People often ask us, why get involved with groups like these? Why not encourage them to be Bnei Noach and keep the Seven Noahide Laws in which they are obligated? But our answer is that when a righteous gentile comes to you and with all their heart says to your face, “I believe in the G-d of Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov and want to fulfill the mitzvos of the Torah,” then who are we to say “no” to them? They will continue to learn and grow in Judaism and move toward conversion and when they are ready they hope a kosher beis din will convert them. Our answer to those who quote the Gemara, “Difficult are converts to Israel like leprosy,” is from the Tosafos themselves, who explain that converts are “difficult” because their starry-eyed devotion and punctilious practice can show us how much piety we as individuals can actually express. —

All that Glitters

The “blue mountain” that Aharon’s ancestors followed is not the only geographic feature of note around Jayapura (previously called Hollandia and the site of a huge US base during World War II). There is also the “golden mountain,” literally a mountain of copper and gold that contains the Grasberg Mine, the largest gold mine and the third-largest copper mine in the world, which employs many of the community members as engineers, technicians, and other skilled positions. The mine’s primary owner is the US company Freeport mines, and it produces well over a million ounces of gold a year, more than 20 percent more than the next-largest mine.

On the “mountain of gold,” the technological and engineering challenges of operating at that altitude where breathing becomes difficult, and at such a remote location, are daunting. Yet the abundance of gold is mind-boggling. Because of its location in the remote highlands of the Sudiman Mountain Range at an altitude of 14,000 feet, many of the community members work a two-week-on/two-week-off schedule. And while on-site, they are even afforded the option of not working on Shabbos.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 687)