Point of No Return

| January 13, 2026As Iran teeters on the brink, is Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi’s long exile over?

As the ayatollah regime teeters, and the blood of ordinary Iranians runs in the streets under a brutal crackdown on protests, a figure from Iran’s pre-revolutionary past has become a rallying cry. Is Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi’s long exile over?

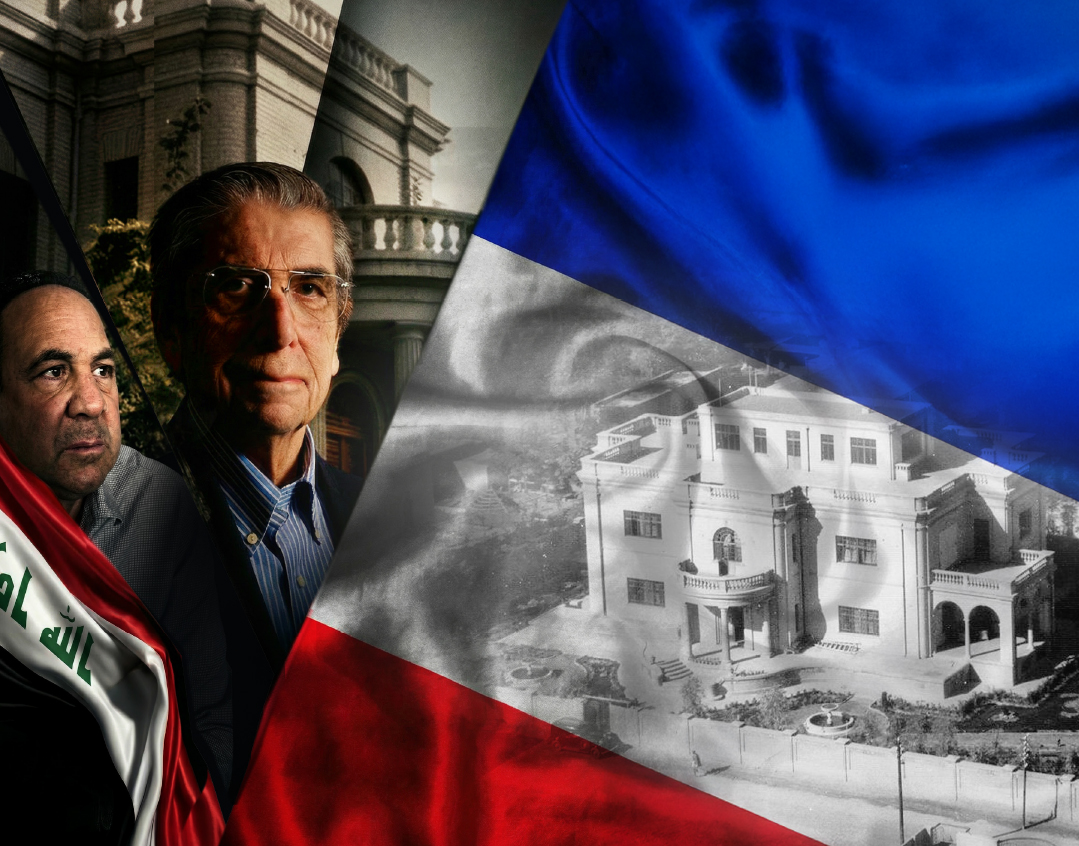

It’s October 26, 1967, and Reza Pahlavi, the seven-year-old crown prince of Iran, moves down the red carpet in Tehran’s Golestan Palace with a solemnity that feels borrowed from someone much older. His uniform is crisp, medals resting on his small chest. He walks deliberately, shoulders squared, eyes forward, mimicking the posture of the courtiers and generals who tower above him.

This is a special day, not just for him, but for his father. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi has already been on the throne for 26 years. He has survived coups, foreign interference, war scares, and the long, grinding work of consolidating power in a country that has rarely known stability. Only now does he feel he has earned the title Shahanshah, King of Kings.

And so, the ceremony unfolds. The crown prince is not merely attending his father’s coronation. He is part of its justification.

As the shah takes his seat on a golden throne, radiant with authority, beside him sits his son on a smaller gold chair — the embodiment of the Pahlavi dynasty’s future.

Fast-forward to October 31, 1980. The room in Cairo’s Koubbeh Palace is splendorous, but in a quieter way that only exile can produce. It’s not a ceremonial quiet, but rather the stillness that settles after history has already moved on. Once the official guesthouse of the Egyptian government, the palace has become the shah of Iran’s final refuge, where Mohammad Reza Pahlavi spends his last months after the seizure of his country by Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamist radicals.

It is here, far from Tehran and stripped of every symbol of power, that his son, Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, is taking an oath not of triumph, but of inheritance. An inheritance without a kingdom. He’s becoming king in name alone, all alone.

Only months earlier, he had been a student pilot in the United States, while his country unraveled thousands of miles away. Now the crown prince stands in a borrowed palace, far from Tehran, far from the crown that had once defined his childhood, surrounded not by ministers of state but by a small circle of loyalists and family friends.

Those present at the unceremonious ceremony in Cairo would have sensed the cruelty of the moment. A king without a kingdom. A crown without consent. A future so uncertain it felt almost cruel to name it aloud.

Trail of Death

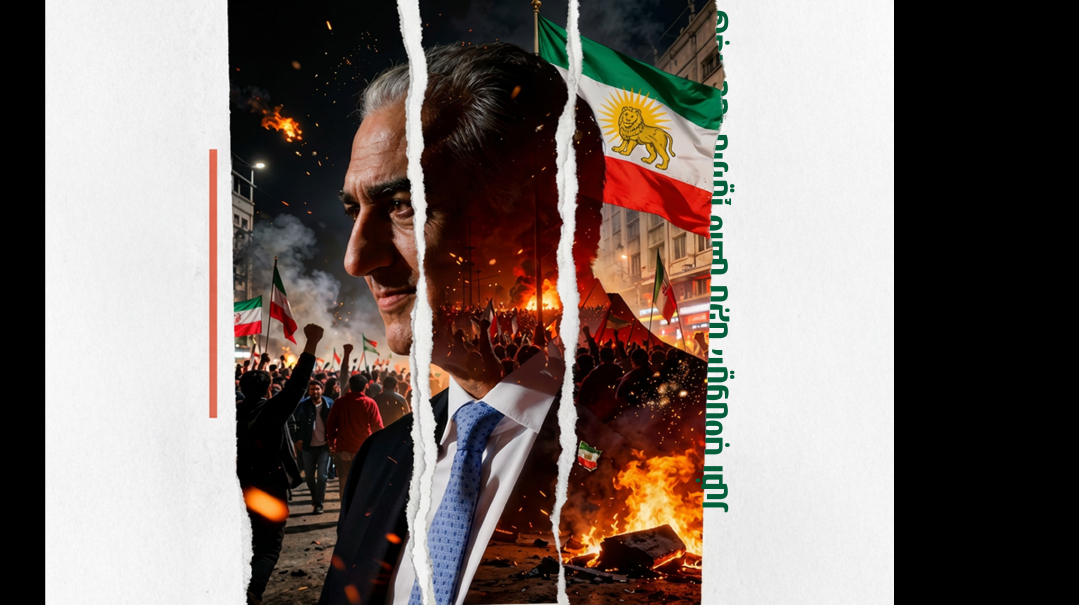

Forward the reel another four decades, and the 65-year-old prince without a throne has been thrust once again into the limelight. After a series of false hopes — protests against the ayatollah regime that flared and were snuffed out, leaving a trail of death and suffering — this time, it seems, may be different. For the last two weeks, ordinary Iranians have been taking to the streets that Reza Pahlavi last saw as a teenager. Amid an Internet cutoff, and braving indiscriminate live fire from the regime’s goons, his former people are acting.

And for the first time, the former crown prince is seen as a rallying point. “Shah, Shah!” protesters across Iran cry as they brandish his old imperial flag emblazoned with the sun and lion, emblems of the Pahlavi dynasty.

Somehow, from his exile in a suburb of Washington, D.C., he’s managed to coordinate a protest movement that now has the regime running scared.

Reza Pahlavi’s possible return would be the culmination of a political saga. But is he really the ruler who can unify a country torn between modernizers and fundamentalists? Judging by his public statements, his restoration would bring a breath of fresh air to the Middle East.

“The first thing a free, democratic Iran would pursue is regional stability, cooperation, and cordial relations with its neighbors,” he has said. “It would not be driven by an ideology rooted in hatred of Jews.”

That regional realignment would be built on a process of reconciliation at home, he says, noting that he’s reached out to his father’s biggest opponents to offer them an olive branch in a new Iran.

As the killing goes on across an Iran now cut off from the outside world, the next stage surely depends on the Iranian people. If they can withstand the pent-up brutality of the cornered savages who rule them, then Iran has a chance to set the clock back — perhaps all the way to Reza Pahlavi himself.

Man of Contrasts

The once-and-possibly-future king is someone I’ve seen up close in D.C. I had the chance to speak to him one-on-one a year ago, after a press conference he gave. Onstage, Reza Pahlavi is in control. If you listen to him addressing a think tank, or hear him on American media, he comes across as measured and impeccably prepared. He speaks like a man who has spent a lifetime studying for an exam he never knew when he’d be allowed to take. Every answer is deliberate, and every sentence feels stress-tested. Watching him under the lights, you get the sense that this is someone who has been rehearsing since childhood.

But when the cameras go dark, something shifts. In private, the stiffness melts away. He’s warm, he’s jovial, he’s curious. He can dish a joke and he laughs easily. There’s an unmistakable humanity there that’s less crown prince and more personal.

I walked away from our meeting struck by the contrast. The public persona projects gravity and restraint. The private presence radiates approachability and ease. And it left me wondering why he doesn’t let the world see more of that side. Is it discipline? Is it part of some strategy? Or is it the product of a lifetime of learning that warmth can be mistaken for weakness?

That lifetime of schooling in opposition unfolded in stages, each one stripping something away.

After the revolution, Reza Pahlavi’s life became a series of departures. Morocco. The Bahamas. Mexico. A few weeks here, a few days there. A brief, uneasy stay in the United States as his father, the shah, battled lymphoma. Panama. Then Egypt, where his father would die and where the crown prince, barely 20 years old, would take an oath in a country that granted him refuge, to a country he could no longer enter.

Egypt offered dignity and privilege but not direction. The crown prince didn’t settle down for too long, moving time and again, through France and England — often welcomed politely, sometimes refused outright. In West Germany, he was barred entry. The message was blunt: Whatever he represented, having him as a guest was still too volatile.

As early as 1982, just three years after the revolution, there were clandestine attempts to reinvent Iran without Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. According to The Iranian Triangle, a book by former Israeli military intelligence officer Samuel Segev, a secret plot that year sought to overthrow the regime with the backing of Israeli and American intelligence figures. The plan, which had the approval of CIA director William Casey, envisioned supplying hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of arms and military training to Iranian officers opposed to Khomeini.

Reza Pahlavi made contact and hosted meetings that helped give shape to the idea, a Saudi financier explored funding, Israel weighed supplying weapons, and Sudan was floated as a potential training ground. But the plot collapsed almost as quickly as it formed, undone by Israeli political upheaval and doubts about its chances of success. Many of the intermediaries involved would later resurface in the Iran-Contra Affair, underscoring how tangled and unstable early efforts to confront the Islamic Republic truly were.

What the plot revealed is that in the early years of exile, opposition to the regime was fragmented and foreign-dependent. It was driven by covert maneuvering rather than popular legitimacy. The crown prince learned this lesson early, that regime change engineered abroad is doomed to collapse under its own weight. Whatever Iran’s future would be, it could not be imposed in secret backroom deals.

By the late 1980s, he landed in the United States, far from palaces and far from crowds. Maryland became home. He married. He raised children. He learned what it meant to exist without ceremony, without deference, without the assumption that history would carry him forward. And his politics changed accordingly.

In the early years, his pronouncements leaned toward restoration and a return to power. But both exile and age have a way of clarifying what cannot be recovered. Over time, the language shifted. From monarchy to mandate, from inheritance to consent. He began to speak less about reclaiming power and more about helping return it to the people.

Between his TV appearances and small diaspora gatherings, there were long stretches of silence. He declined to form a government-in-exile, and resisted calls from monarchists to crown himself. Those decisions cost him attention, allies, and relevance. At times, he all but vanished from public view.

Marginal Monarch

For 37 years, Reza Pahlavi lived on the political margins. He was deemed too royal for reformists, too democratic for monarchists, and far too patient for a region addicted to strongmen and shortcuts. He seemed to have become a historical and political afterthought, fated to spend his life waiting for a moment that would never come.

And then Donald Trump returned to office.

Almost simultaneously, Iran’s proxy empire began to wobble. Its militias had become exposed, and its money pipelines strained. And with that shift came a question that hadn’t been taken seriously in decades: What if Iran actually had another option?

It was on January 28, 2025, the second week into President Trump’s second term, that I found myself at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., attending a press conference with Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi. I expected a man making his case for power. What I encountered instead was something far more unsettling to the usual political instincts. A man using the spotlight not to elevate himself, but to force the world to confront the suffering of his people, suffering that for years had been filed away by the international press as tragic and ultimately unavoidable. His priority seemed to be raising awareness about how the people of Iran were being held hostage by a hostile regime.

While his views about his own role may have changed, his views about the Iranian people haven’t. When protests came and went inside Iran, he was still there, unchanged in message. He did not attach himself to a candidate, a reform faction, or a moment. Instead, he argued that the entire system was illegitimate. Only the people could decide who would lead them and what system would replace which. That vision, he has said, requires a transitional pause rather than a rush to permanence.

“I believe there will be an interim government responsible for managing the country’s affairs,” Pahlavi has explained. “During that period, we will call, as soon as possible, for elections to form a parliamentary council — a constitutional assembly — so the nation is fully aware of all the alternatives before it.”

In 1979, the people were never consulted. As far as he seemed to see it, the people themselves never rejected him. He just wanted closure.

Exile took away the inevitability of his crown. What it left him with was patience, and credibility built not on power but on having lived for so many years without it. Especially in more recent years, Pahlavi has made a quiet but consequential pivot. Instead of presenting himself as the natural successor to a fallen monarchy, he now insists that no system has moral authority unless it is chosen freely by the people.

He has stopped talking about what Iran was and instead focuses on what Iran could choose. Constitutional monarchy is one option among many. His role, he argues, is not to rule by birthright, but to help steward a transition away from the Islamic Republic, help stabilize the country, and then take a step back while Iranians decide, by ballot, what comes next.

“If you look at the policies various governments have pursued — whether imposing more sanctions or attempting appeasement, all in the hope that the regime might become more reasonable and return to the negotiating table — none of it has worked,” he has argued. “That failure has been consistent, regardless of whether those Western governments were liberal or conservative, left or right. The reason this approach has only prolonged the regime’s survival is that its very DNA makes coexistence with the free world impossible.”

That evolution mattered, as it reframed him not as a king-in-waiting, but as an internationally transitional figure willing to submit himself to the same democratic test as everyone else. He began saying, plainly and repeatedly, that if Iranians choose a republic, he would accept it; if they chose a constitutional monarchy, that too would be their decision. His ambition, if it could be called that, has narrowed to giving Iranians a real choice for the first time in nearly half a century.

Reactive Protests

For most of those nearly four decades, it felt like a handcuffed arm wrestling against the void. Pahlavi and his message just didn’t seem to pick up.

That wasn’t because Iranians lacked courage. It was because earlier protest cycles were reactive, not yet existential. In 1999, the streets filled with crowds demanding student press freedoms. In 2009, the streets filled again, over a stolen election and a specific candidate. In 2022, rage erupted after the death of Mahsa Amini and the brutality of the morality police.

The past decade also saw waves of strikes over economic mismanagement and, more recently, protests sparked by worsening water shortages. Each movement burned hot, but none fully cohered. They were infused with passion, but they lacked in a unifying figure, someone capable of channeling protest into a national purpose.

And each time, the protests were ultimately framed as corrections, not rejections. Fix this law, count that vote, punish that official, remove this practice. Even when crowds shouted, “Death to the dictator,” the anger was still reactive and aimed at symptoms, not at the system itself.

Pahlavi, meanwhile, stood outside all of that. He wasn’t tied to a stolen ballot. He wasn’t a reformist insider. He wasn’t even a response to a single injustice. He was proposing something much more destabilizing: the end of the entire structure. For years, that idea had arrived before the people were ready to hear it.

Even as recently as last year, during heightened regional tensions and open confrontation between Iran and Israel, Pahlavi issued calls for nationwide protests and military defections. They were not widely answered.

And then something changed. This time feels different.

Today’s protests are no longer reactions to a moment. They are indictments of a pattern.

Iranians are no longer asking, “Why did you do this?” Instead, they are asking, “Why is everything broken?”

And the answer keeps coming back the same. Because the regime has spent decades squandering national wealth on proxy wars, while letting the country rot from the inside out. Because billions were flowing to Hamas, Assad, Hezbollah, the Houthis, and militias across the region while Iran’s own infrastructure was collapsing. Because water was running out.

Entire provinces are facing severe water shortages, not due to drought alone, but due to catastrophic mismanagement, corruption, and ideological indifference. Rivers that once sustained agriculture are dry. At the same time, food prices have exploded. Basic staples have doubled and tripled in cost.

Iranians understand now that as long as the Islamic Republic exists, nothing improves, because that’s what’ll happen when every solution requires international cooperation and every path to cooperation is blocked by a regime obsessed with exporting revolution and courting apocalypse. So this time, the anger is not episodic, it is existential. And this is why Pahlavi suddenly resonates.

Long Live the Shah

Pahlavi reenters the story as the singular individual with international recognition who’s been out there speaking out for the Iranian people long before anyone who would listen to him. For decades, he said the same thing while everyone else tried everything else.

“Javid Shah! Javid Shah!”

Ten years ago, it would have been dismissed as fringe nostalgia. Five years ago, it would have been a suicidal provocation. Even as recently as last year, analysts would’ve laughed it off. And now, it echoes across cities, towns and villages, shouted by people who know exactly what it costs to say it.

It’s a chant not of coronation, but of rejection. Not aimed at restoring the monarchy of the past, but at ending this nightmare of the present.

Pahlavi sees it clearly.

When I spoke with him privately after the press conference, he laid out what a democratic Iran would do in its first days. Cut off funding to Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis. End proxy warfare. Reenter the international system. Redirect national wealth inward instead of outward. One regime change, he argued, would collapse entire terror networks overnight and reframe the region’s overwhelming net negative into an overpowering net positive. Israel and the United States would lose a mortal enemy and gain a regional ally, resulting in a recalibrated Middle East.

I told him that just as many of us have come to see G-d’s wisdom in removing Donald Trump from power for four years only to return him sharper and better prepared, I pray that one day we will understand the wisdom behind the 40 years Pahlavi has spent in exile, so that he would be uniquely positioned when both he and his people were finally ready to take back their county together.

While revolutions are never neat and history doesn’t move on schedule, for the first time in decades, the Iranian protests seem to be embracing their advocate, who’s been as ignored by the rest of the world as they’d been themselves.

And for the first time, the chants of “Long live the Shah,” and “The Shah will return,” are not echoing into the void. This time, it sounds like it might be answered.

Trump Card?

One question still hangs over all of this like an unanswered text message. If the momentum behind Reza Pahlavi is real, why hasn’t Donald Trump embraced him outright?

And the answer has less to do with Iran and almost everything to do with Trump. In fact, this is how Trump always operates in moments like this. He knows exactly how much gravity his endorsement carries, and he is deeply allergic to would-be rulers who treat American backing as a shortcut around legitimacy. He’s seen this script before, where opposition figures convince themselves that a tweet and a photo op in the Oval Office can substitute for a mandate back home.

Trump doesn’t play that game. He prefers leverage over niceties, outcomes over declarations, and, above all, proof. Proof that a leader isn’t being assembled abroad and shipped home shrink-wrapped but summoned organically from within. He doesn’t want to create legitimacy; he’d rather wait to recognize it once it becomes undeniable.

Pahlavi understands this. Which is why he hasn’t tried to force Trump’s hand.

Instead, he speaks in Trump’s political dialect. He’s branded his vision Make Iran Great Again, MIGA, an unsubtle but intentional signal that a post-Islamic Republic Iran would be nationalist, sovereign, representative, and economically focused.

He’s also gone a step further, floating a concept he calls the Cyrus Accords, a deliberate extension of the Abraham Accords framework into Iran. Named not for his own family but for Cyrus the Great, the ancient Persian king remembered for tolerance, minority rights, and allowing exiled Jews to return home. Where the Abraham Accords normalized relations between Israel and Arab states willing to abandon perpetual war, Pahlavi argues that a free, democratic Iran could transform the region’s most destabilizing actor into one of its anchors.

And still, Trump waits. His instinct has always been to wait until the will of the people is no longer debatable. In that sense, Trump’s silence isn’t a snub, it’s a test.

And Pahlavi, for his part, seems content to let the people take it, knowing that if and when Trump does move, it won’t be because he was persuaded in Washington, but because something became impossible to ignore in Tehran.

Shedding Illusions

To better understand why this transition is happening now and why it looks so different from every Iranian uprising that came before it, I sat down with Khosro Isfahani, a senior analyst at National Union for Democracy in Iran. He painted a picture not of sudden revolt, but of long political maturation that is slow, painful, and finally decisive.

Isfahani has been watching Iranian protest cycles for nearly his entire life. Literally.

“I have been involved in Iran’s protests since I was eight,” he tells me, recalling how his father took him to the 1998 student protests, which made demands that were modest in retrospect. “The student protesters were on the streets calling for just a slight change to media rules in Iran, giving the local print papers a chance to slightly criticize the regime.”

And even that was too much.

“Iranians have been on the streets since 1979,” he says. “Nothing is new. What’s changed is what they are asking for. What distinguishes the current protest movement compared to the past cycles is that the Iranian nation has gradually matured in terms of its political identity.”

The illusions of 1979 that Islamist rule could deliver justice, dignity, or prosperity have collapsed under the weight of lived experience, Isfahani says. “The people have shed their belief in Islamist ideology and moved away from it.”

That maturation has produced clarity, both about what must go and who can plausibly lead a transition. In protest after protest, Isfahani notes, “people are chanting the name of Reza Pahlavi. They are calling for his return. They are calling for fundamental change. The Islamic Republic in its entirety has got to be dismantled so we can build Iran again.”

Just as important as what is being said is where it’s being said. Unlike previous cycles concentrated in major urban centers, this uprising has spread across provinces, towns, villages, and universities.

“When protests spread this far into the countryside,” Isfahani says, “it causes fatigue very fast among security forces. In major urban areas like Tehran, mobility is easy and the security forces can be concentrated. When the protest spreads to smaller towns and villages, security forces are stretched too thin. They’re forced to do multiple shifts around the clock and are constantly being mobilized to different locations. That can break the system.”

He explains why law enforcement in villages have not only been standing down, but in some occasions even joining the protests. “When you are dealing with protesters in a major city like Tehran that has a population of millions of people, you don’t know whom you are beating. But in a village, everyone knows your name, everyone knows your family. So you would hesitate before doling out violence against them.”

Then there is the bazaar. The same merchant class that helped finance the 1979 revolution has now turned decisively against the regime it once empowered.

“It’s absolute insanity to invest in Iran,” Isfahani says. The collapse of the currency, the rial, and runaway inflation imposed a stark choice on business owners: Either pull everything out, or force change. “The sudden drop in the value of the national currency was a psychological trigger.”

And when the economy entered the abyss, Isfahani says, class lines were erased. “Immediately, the lower classes of workers, farmers, people with nothing to lose joined the same call.” With food prices doubling and basic survival in question, “they know that if the Islamic Republic remains in power, they cannot afford to live.”

United for Life

The regime has faced popular anger before over the last 37 years, but always from isolated sectors of society — students, workers, liberals. There has never been a unified opposition, or a leader around whom they could coalesce. And then there is the contrast that keeps resurfacing.

“From all the opposition movements that have come and gone over the past four decades,” Isfahani says, “a single individual has held up what he has always said. [Pahlavi] has never changed his principles. He has never made concessions to the Islamic Republic. When you have a leader who is clear about his principles for four decades, you can trust him.”

The regime’s traditional approach to managing opposition has been to stir anger at the foreign infidels, and to portray total war against them as a holy cause. The highest calling, the mullahs declared, was martyrdom in service to that cause. And now, in the throngs calling for their ouster, the authorities face a challenge for which they have no answer.

“Iranians are not calling for death,” Isfahani says. “They are calling for life.”

He contrasts a regime that celebrates martyrdom and destruction with a people who, even through bloodied streets, “went back home, sang, danced, drank, celebrated life.” That instinct to live, not to die for ideology is what now binds the protests together. It’s a hill they’re willing to die upon.

“The Islamic Republic is a threat to anyone that lives on planet Earth,” Isfahani says, “and Iranians are on the front line of the fight for saving life on Earth. We are willing to die to remove this regime.”

This uprising, he explains, is no longer about outrage at a single injustice, but exhaustion with a system that cannot be fixed. “As long as the Islamic Republic exists,” Isfahani says plainly, “none of Iran’s crises can be solved.”

Isfahani also dismisses, almost impatiently, the recurring rumors that Ayatollah Ali Khamenei might consider leaving the country. That, he says, misunderstands the man entirely. Khamenei is not scanning exit routes or lining up safe harbor abroad.

“He’s going to stay,” Isfahani says flatly. “He’s going to stay in the capital.”

Khamenei views himself not as a ruler who might lose power, but as a figure with a divine role to fulfill. In Isfahani’s telling, that belief makes him more dangerous, willing to kill thousands, even to die himself, rather than concede defeat. The regime’s endgame, he warned, will not be negotiated exile, but a willingness to burn everything down rather than relinquish control.

Another False Hope?

Taken together, Isfahani’s analysis suggests that what Iran is experiencing now is not merely another uprising, but the closing of a long political loop. This moment feels different not because the anger is louder, but because it is clearer.

And yet clarity does not guarantee outcome.

A figure long dismissed as peripheral, Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, has reentered the conversation not as nostalgia, but as contrast. His name now echoes in places where whispering it would have once been unthinkable. But resonance is not the same as authority, and chants are not yet governance. Iran’s history is littered with moments when unity appeared suddenly, only to fracture under the weight of what came next.

Even Isfahani, for all his confidence in the movement’s maturation, does not pretend the path ahead has been settled. The regime remains intact, armed and convinced of its own divine mandate. The opposition, newly aligned in purpose, has not yet been tested by power, compromise, or the inevitable questions of transition.

For decades, Iranians have learned what does not work. What they’re urgently hoping to settle is whether this moment can carry them from rejection to reconstruction. Whether Reza Pahlavi becomes a bridge, a placeholder, or a footnote again will depend on what happens next inside Iran, where the pressures are endless and any guarantees premature.

Still, the chants are real, the anger is real, and the opening may be real as well. Whether Iran steps through it or watches it close again may be decided soon enough.

The Shah Is Now

Iranian expatriates believe the moment has come for the exiled king to reclaim his land

By Yitzchok Landa

T

he fastest way to make a bad situation seem manageable… is to end up in a worse one.

With this in mind, those lucky enough never to have lived under tyranny are suspicious of Iranian enthusiasm for the return of the old monarchy, led by His Royal Highness Reza Shah Pahlavi. True, his family’s rule in Iran wasn’t as bad as that of the ayatollahs; but was it really that great? Weren’t there mass protests in the streets against his father in 1979?

Would it be bleary myopia to overthrow Ayatollah Ali Khamenei just to bring back the shah?

Yosef Cohen,* an Iranian expat living in New York, was one of the protesters filling the streets in 1979, chanting “Death to the shah.” But his true feelings, he tells Mishpacha, couldn’t have been further from what he said in those days.

“People love the shah [Farsi for king],” he says. “His rule was great — the country was successful and people were happy. The Islamic fundamentalist revolution overthrew him, and we knew he was a goner. We demonstrated in the streets against him because we were forced to — we knew the incoming regime would have punished anyone who didn’t.”

Since coming to the United States in the years following the rise of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Cohen has remained closely connected to his home country while loyal to his host country. He’s part of a network of Iranian agitators around the globe that closely follows events in Iran, lobbies for change, and maintains contacts in der alter heim.

This Time’s the Charm

Like most of his colleagues, he is excited about current events and believes we stand at a consequential moment.

Cohen doesn’t believe for a moment that regime forces have killed only a few hundred protesters. “They didn’t shut down the Internet all over the country to hide the murder of as many people as they sneeze to death any other time,” he says.

Destruction of the evidence is the greatest proof of the scope of the crime. The word within the network tallies over 2,000 protesters executed by regime Basij forces, Cohen reports. He has heard of over 10,000 injured, with corpses piling up in the streets and doctors overwhelmed. Another Iranian expat, activist Patrick Bet-David, reports similar numbers.

The Internet blackout in Iran was not imposed to prevent the unrest from organizing, but to deter Trump from making good on his threats, both say. Information leaked out to network stations in London and the US for the first few days of protests, transmitted around connectivity smothering via Elon Musk’s Starlink system. But Iran then brought in Chinese-made microwave jamming technology to disrupt the satellite-based service, with the side effect of crippling all cell phone service in the country — severely limiting command and control even among the regime forces.

“The protesters aren’t affected by the loss of Internet,” Cohen explains. “They aren’t deterred by the killings this time either. They’re driven to the streets because they have nothing to eat or drink, they have no money with which to live. People acting out of desperation don’t need an organizing or coordinating force, and it seems that no amount of violence will keep them inside… they no longer have anything to lose.”

Videos that made the rounds on Iranian social media before the Internet shutdown showed a warehouse filled with gold bars, Cohen testifies. These were payments in blood money to Russia and France for their economic support, as well as funding for Hamas and Hezbollah. The clips served to infuriate the starving Iranian people to their breaking point.

This is why the moment now seems bigger than it has ever been during previous rounds of protests.

And because of Trump.

Fear the Unpredictable

“What’s different this time is the man in the White House,” Bet-David says. “Khamenei was stunned when Trump killed Qassem Soleimani. That was when it dawned on him that this president was different.”

Thus began the Islamic Republic’s grudging respect for the Donald Republic. Operation Midnight Hammer and afikomen games played with Maduro solidified that fear, “forcing the regime to hide its cruelty and hatred for its own people.”

Cohen insists Pahlavi is the answer. “Everybody wants him, everybody loves him,” he says.

“People are burning not just government buildings, but mosques,” Bet-David adds. “That is a significant statement — it shows their anger to be directed at the Islamism of the regime, not just its politics. They are saying, ‘We are Persians, not Islamists. We want our shah, not a cleric.’ ”

Speaking on Fox, the 65-year-old Pahlavi adopted a diplomatic tone: “In the last 48 hours, Iranians have suffered more casualties than America did after the 9/11 attack… [that’s why] this is a defining moment and an opportunity to liberate that great nation.”

Ayatollah Khamenei himself is nowhere to be found in Tehran, Cohen’s spies say; he’s already prepared getaway vehicles for himself and his top aides, and they’ve already sent their wives and families to Russia.

“No one knows where he is… he’s in hiding some 200 miles away from everything,” Cohen reports. “Only the Mossad knows where he is. But they won’t kill him, because they don’t want this to be framed as a Jewish attack on Muslims.”

Khamenei has already named his son, Mojtaba Khamenei, as successor — “just as big a rasha as his father,” Cohen explains. The younger Khamenei helped elect Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, architect of Iran’s nuclear aspirations, as president, and crushed street protests in 2009. He also coordinated funding for Hezbollah and led attacks on Israel.

Like most Iranian exiles, Cohen has lost contact with any family or friends among the 15,000 to 20,000 Jews left in Iran. He’s worried about them, but not as much as you might think. “They always live with risk, but it’s not a crime to be Jewish in Iran. The regime’s reading of the Koran recognizes Judaism as a legitimate religion, which gives Jews a degree of protection.”

It is connections to Israel that can get one snatched or killed in Ayatollahstan. Jews in the country keep a very low profile — something as innocent as a selfie at the Kosel can trigger accusations of spying for Israel and an unscheduled, permanent disappearance.

Cohen reminds us of a perspective that is important to always stress when observing world events. “Ultimately, Hashem is always in charge,” he says. “Whatever He decided is what will be, whatever He decreed is for the best. While 1979 was a disaster for most people, it was the best thing for me… it’s what led me and so many other Iranian Jews to become frum. I don’t see that I would ever have become shomer Shabbat living in Iran.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1095)

Oops! We could not locate your form.