Piety in Pittsburgh

| June 4, 2024Rabbi Sivitz was considered one of the leading Russian rabbanim in America

Title: Piety in Pittsburgh

Location: Pittsburgh, PA

Document: The Jewish Standard

Time: June 1917

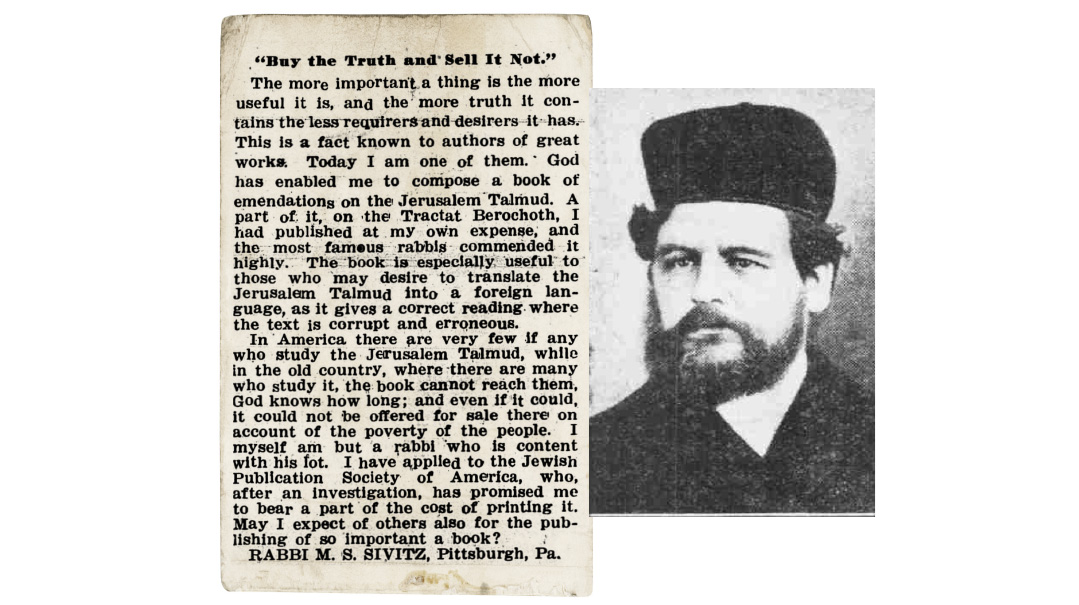

Lovers of the Talmud can now have a rare treat in the valuable commentary on the Talmud Yerushalmi of Rabbi M. S. Sivitz, of Pittsburgh, Pa., which he has called “Mashbiach.” Although the title was chosen by the author to link the initials of his father’s name with his, he could not have named it more appropriately, as “Mashbiach” means “that which improves,” and it is many years since we have seen any work that improves the study of the Yerushalmi as does the “Mashbiach.”

The Talmud of Jerusalem is well known to possess many passages whose meaning is very obscure, but these very mysterious allusions are replete with gems of the most brilliant luster, and it has remained for the erudite Rabbi Sivitz to cast the searchlight of his great rabbinical knowledge and keen wit upon them and uncover them for the delight of those who love our ancient sages and their sayings.

For thirty years, Rabbi Sivitz has not alone filled the illustrious position of rabbi in Pittsburgh, preaching ancient wisdom in modern and popular language that appeals to the masses as well as the classes, but he has been at the head of every movement for the up-lift of Pittsburgh Jewry. And yet this remarkable man has found time to write many volumes of homiletics on the written and oral law, any one of which would be sufficient to preserve his name and fame for generations to come, but his latest work, “Mashbiach,” is certainly his chef d’oeuvre. It is a veritable masterpiece in modern rabbinic literature.

To those of our co-religionists who pride themselves on the possession of a fine library of Hebraica, to those who believe that from Zion will come forth the Torah and the word of the L-rd from Jerusalem, we cannot too strongly recommend the acquisition of this latest treasure in Talmudic lore. “Mashbiach” brings back to us the beloved sages of our Holy City, Jerusalem; it makes us understand their language and appreciate their wisdom. By the light of this wonderful commentary we again exclaim, “There is no wisdom like the wisdom of the sages of Jerusalem.”

—The Jewish Standard, March 3, 1919

Rav Moshe Shimon Sivitz (1855–1936) was born outside Kovno and studied in the Telz Yeshivah, where he was ordained by its rosh yeshivah, Rav Eliezer Gordon (1841-1910), and later by the Kovno Rav, Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor (1817-1896). He continued his studies in Kovno and, at about the age of 30, became a rav in Pikelen, Lithuania. In 1886, he immigrated to the United States, where he accepted a position as rabbi of the Russian Shul in Baltimore. Within two years, he moved to Pittsburgh to serve as rabbi of Bnai Israel and later of Kahal Yereim. Ultimately, he would spend nearly half a century as the leading Orthodox rabbi in the Steel City.

Well beyond his pulpit, Rabbi Sivitz was considered one of the leading Russian rabbanim in America. At the funeral of Rabbi Jacob Joseph (1840–1902), he delivered a fiery hesped, admonishing the crowd for their mistreatment of the Rav Hakollel. He berated those gathered for their lack of priorities, citing the fact that their rabbis were paid less than the cantors of the time, and pointing out that the rabbis’ lack of economic independence compromised their authority.

Shortly thereafter, he was involved in the founding of the Agudath Harabbonim and served as one of its leaders for three decades. Along with Rav Eliezer Silver (1882–1968) and others, he served many times on a beis din to adjudicate issues still remembered in American halachic lore.

Pittsburgh had long been a center of Reform Jewry. Reform leadership convened a conference in the city in 1885, where they agreed upon eight principles that they called the “Pittsburgh Platform.” It characterized Judaism as a progressive religion embracing reason and science, rejecting traditional halachos such as kashrus, and declared Jews a “religious community” rather than a nation. It also removed all mention of return to Israel from its prayer books.

When the Reform community opened an orphanage, Rabbi Sivitz discovered that the children were being brought up without any religious instruction, and the home lacked a kosher kitchen. He decided to assist poor widows by distributing a dollar per week for each orphan so the children could be raised in their own homes rather than in the orphanage. He also founded the Society of Bikur Cholim, the Hebrew Hospital, and the House of Shelter, and helped establish a women’s organization that assisted with maternity cases among the poor. Rabbi Sivitz never turned a stranger away from his door, offering assistance to all.

Following the 1901 assassination of President William McKinley, who was shot by professed anarchist Leon F. Czolgosz, Rabbi Sivitz delivered a well-attended eulogy for the president in which he harshly criticized the anarchy movement. Shortly thereafter, he became a target for violent anarchists.

He shared how late one night, while he worked in his study on his commentary on the Yerushalmi, there came a knock at the door. When his wife opened it, three men entered. One of them drew a revolver and aimed it point-blank at Rabbi Sivitz, declaring their intent to murder him for his interference in their work. Undeterred, Rabbi Sivitz boldly told them to go ahead and shoot, because if G-d had decided that it was his time to depart this world, he would accept His judgment. Instead of firing, the men turned to each other and suddenly fled the Sivitz home.

Twenty years later, while Rabbi Sivitz was sitting with his family at dinner, a man entered the house, smiled at him, and inquired if he recognized him. Rabbi Sivitz did not. The man revealed that he was the one who had pointed the revolver at him that night. Curious, Rabbi Sivitz asked what had deterred him from carrying out the act. The man explained that had Rabbi Sivitz shown fear, he would have completed the deed. However, seeing that Rabbi Sivitz was prepared to sacrifice himself for his ideals, they decided he should not be harmed.

Rabbi Sivitz authored many seforim, but his crowning achievement was the 1913 publication of the first volume of Mashbiach, his commentary on Talmud Yerushalmi, one of the few available at the time. He later added a second volume in 1918. The widely acclaimed work included a rare approbation from the Chofetz Chaim.

Sadly, Rabbi Sivitz endured a number of tragedies in his life. His first wife, Maita, died in 1919, and his second wife, Chaya Esther, passed away a few years before him. In addition, he buried his two-year-old daughter in 1902 and his son Shmuel in 1923.

Rabbi Sivitz the Shadchan

At the 1908 Agudath Harabbonim convention in Philadelphia, Rabbi Sivitz encountered a young Rabbi Dr. Bernard Revel. This meeting serendipitously aligned with Rabbi Sivitz’s acquaintance with the affluent Travis family of Marietta, Ohio, immigrants from Riga who had prospered in the oil industry. The Travis family, staunch Lubavitcher chassidim and supporters of important Torah causes worldwide, often sought Rabbi Sivitz’s guidance due to the absence of a local rabbi in Marietta.

During a visit in 1908, Rabbi Sivitz met Sarah Travis, the daughter of the family patriarch Isaac. Seeing a potential match, he suggested that Sarah meet Bernard Revel (1885–1940), who was then working as an assistant rabbi to his Agudas Harabbonim colleague, Rabbi Bernard Levinthal (1864–1952) in Philadelphia. On Thanksgiving Day of that year, Revel visited the Travis home, which led to their subsequent marriage that summer, with Rabbi Sivitz officiating at their wedding.

Torah Benevolence

As is customary for authors, Rav Yitzchak Yaakov Ruderman (1900-1987) sent his new sefer, Avodas Levi, to prominent rabbanim he thought would enjoy studying it. One of these recipients was Rabbi Sivitz. In appreciation, Rabbi Sivitz sent Rav Ruderman $50, a substantial sum at that time. Rabbi Sivitz later explained to Rav Ruderman that he had received a gift of $20,000 from the Pittsburgh community following a monumental anniversary, and realized that having this large sum disturbed his peace of mind and interfered with his ability to concentrate on learning. To resolve this, Rabbi Sivitz decided to distribute the money to yeshivos and to authors of seforim.

Rav Meir Dan Plotsky (1866–1928), the author of Kli Chemdah, was another such recipient, receiving a grant of $200 from Rabbi Sivitz for a sefer he had published. In a short time, Rabbi Sivitz managed to rid himself of the unwanted financial burden, allowing him to regain his focus and tranquility.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1014)

Oops! We could not locate your form.