Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

| June 9, 2024In 1924, three Torah luminaries journeyed to the US to secure financial aid for Torah centers ravaged by the First World War

Photos: Yeshiva University Archives, National Library of Israel, Library of Congress

Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Document: Various documents and photos

Time: 1924

Blossoming the Flowers of American Jewry

In 1924, three Torah luminaries journeyed to the US to secure financial aid for Torah centers ravaged by the First World War. While their fundraising efforts fell short of their goals, the visit of these revered figures was a landmark event that stirred the hearts of American Jews, greatly reinforcing their connections to their European counterparts and the nascent Jewish community in Palestine

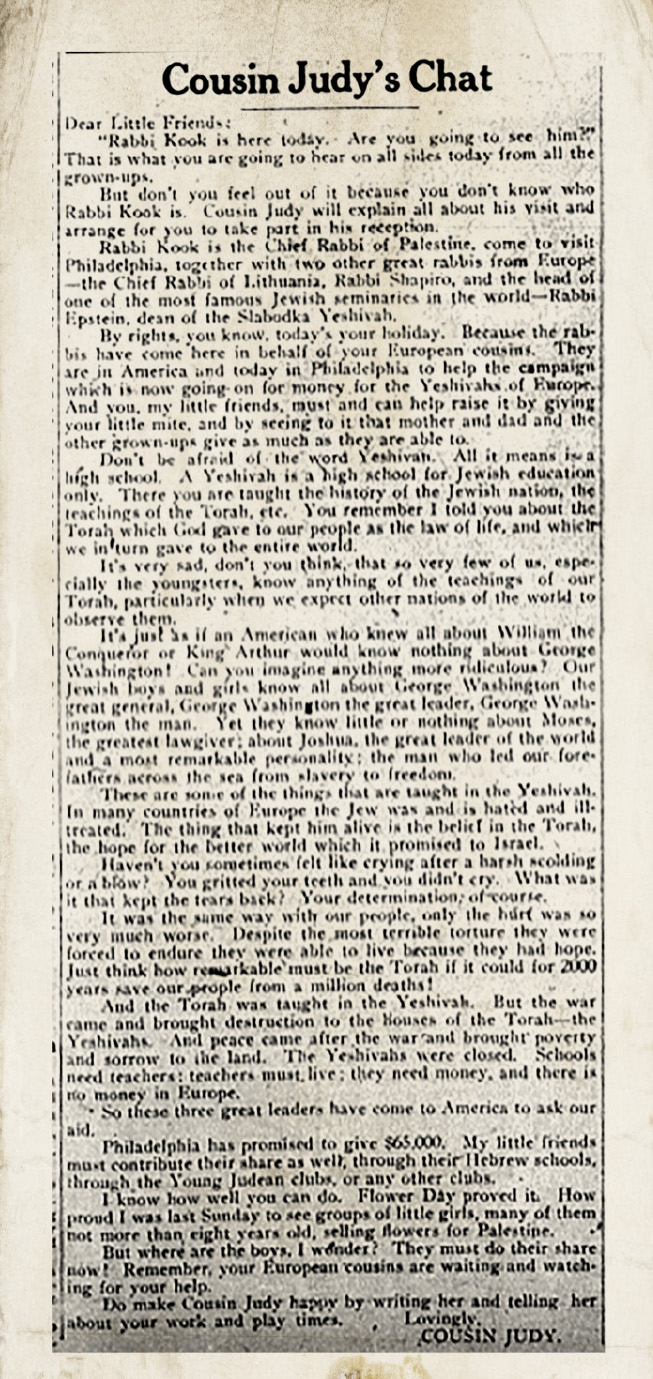

Cousin Judy’s Chat

Dear Little Friends,

“Rabbi Kook is here today. Are you going to see him?” That is what you are going to hear on all sides today from all the grown-ups. But don’t you feel out of it because you don’t know who Rabbi Kook is. Cousin Judy will explain all about his visit and arrange for you to take part in his reception.

Rabbi Kook is the Chief Rabbi of Palestine, come to visit Philadelphia, together with two other great rabbis from Europe — the Chief Rabbi of Lithuania, Rabbi Shapiro; and the head of one of the most famous Jewish seminaries in the world — Rabbi Epstein, dean of the Slabodka Yeshivah.

By rights, you know, today’s your holiday. Because the rabbis have come here on behalf of your European cousins. They are in America and today in Philadelphia to help the campaign which is now going on for money for the Yeshivahs of Europe. And you, my little friends, must and can help raise it by giving your little mite, and by seeing to it that mother and dad and the other grown-ups give as much as they are able to.

Don’t be afraid of the word Yeshivah. All it means is a high school. A Yeshivah is a high school for Jewish education only. There, you are taught the history of the Jewish nation, the teachings of the Torah, etc. You remember I told you about the Torah, which G-d gave to our people as the law of life and which we, in turn, gave to the entire world. It’s very sad, don’t you think, that so very few of us, especially the youngsters, know anything of the teachings of our Torah, particularly when we expect other nations of the world to observe them?

It’s just as if an American who knew all about William the Conqueror or King Arthur would know nothing about George Washington! Can you imagine anything more ridiculous? Our Jewish boys and girls all know all about George Washington, the great general, George Washington, the great leader, George Washington, the man. Yet they know little or nothing about Moses, the greatest lawgiver; about Joshua, the great leader of the world and a most remarkable personality; the men who led our forefathers across the sea from slavery to freedom. These are some of the things that are taught in the Yeshivah. In many countries of Europe, the Jew was and is hated and ill-treated. The thing that keeps him alive is the belief in the Torah, the hope for the better world that it promised to Israel.

Haven’t you sometimes felt like crying after a harsh scolding or a blow? You gritted your teeth, and you didn’t cry. What was it that kept the tears back? Your determination, of course. It was the same way with our people, only the hurt was so very much worse. Despite the most terrible torture they were forced to endure, they were able to live because they had hope. Just think how remarkable must be the Torah if it could, for 2000 years, save our people from a million deaths!

And the Torah was taught in the Yeshivah. But the war came and brought destruction to the houses of the Torah — the Yeshivahs. And peace came after the war and brought poverty and sorrow to the land. The Yeshivahs were closed. Schools need teachers: teachers must live; they need money, and there is no money in Europe.

So these three great leaders have come to America to ask for our aid. Philadelphia has promised to give $65,000. My little friends must contribute their share as well, through their Hebrew schools, the Young Judean clubs, or any other clubs. I know how well you can do. Flower Day proved it. How proud I was last Sunday to see groups of little girls, many of them not more than eight years old, selling flowers for Palestine. But where are the boys, I wonder? They must do their share now! Remember, your European cousins are waiting and watching for your help.

Lovingly,

COUSIN JUDY.

(COUSIN JUDY was the pen name used by an Orthodox woman who wrote regular English advice columns to the youth in Philadephia’s Yiddishe Velt newspaper. While her identity remains unknown, we have some suspicions about who she might have been.)

The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 was a watershed moment in both the history of the United States and Jewish history of the 20th century. Over decades of largely unrestricted immigration, nearly three million Jews had escaped from economic hardship and governmental repression in Eastern Europe to the promise of the New World. This came to an end in 1924, when the US Congress curtailed further immigration through draconian quotas. While the Johnson-Reed Act had far-reaching consequences for the millions of Jews in Eastern Europe hoping to immigrate, it also unintentionally influenced the trajectory of American Jewry itself.

Within the flourishing immigrant communities, there was a tacit understanding that the flow of immigrants from the alte heim would never cease. That meant a limitless supply of spiritual guidance: religious leaders and educators arriving on American shores on a regular basis. This unspoken reliance on the bridge to the old country meant that much of the American Orthodox infrastructure of the early 20th century was underdeveloped.

All of that came to a sudden halt with the Immigration Act of 1924. The flow of immigration almost instantly dried up, and American Jewry was forced to mature, define its identity, and find its own distinctive path. This took many years and was only fully realized after the destruction of European Jewry during the Holocaust. But the seeds were planted while Congress deliberated the legislation. Exactly 100 years ago, three great Torah leaders visited the United States and infused the Jewish community with a sense of identity and mission. This historic sojourn paved the way for a confident, independent, and traditional American Jewish community to take a leadership role in world Jewry.

World War I laid waste to the bulk of Eastern Europe. Homes were turned into battlefields, and many displaced Jews were left impoverished refugees. The Bolshevik Revolution and subsequent Russian Civil War caused mayhem across the former Pale of Settlement. In Ukraine, tens of thousands of Jews were murdered in pogroms in 1918-19. There was no economic stability; Jewish educational institutions, community infrastructure, and religious life nearly shut down entirely. Rebuilding seemed an almost insurmountable challenge.

As World War I unfolded, American Jewry had rallied to aid European Jewry with the philanthropic Joint Distribution Committee. After the war, different organizations within the Joint were assigned to distribute funds to recipient communities. The Central Relief Committee, established by the Agudath Harabonim, turned to rehabilitate the spiritual life of European Jewry after the upheaval of the war.

The Central Relief Committee launched a much-publicized visit of great rabbinical personalities, who would meet the public and bring attention to the desperate financial needs of Europe’s yeshivos. This emergency fundraising campaign was viewed as the only way to rescue yeshivos at this crucial juncture.

This was not the first group of rabbis to attempt a trip like this; however, it was certainly the highest-profile one. Shadarim had been visiting since the American Revolution. Some collected money for the Yishuv in Palestine while others raised funds for Volozhin, Mir, and Slabodka during the late 1800s. The emissaries were treated with little respect and often hostility by their fellow Jews, even as Eastern-European Jews — some who had even studied in those yeshivos — became more ubiquitous.

Perhaps the first major voyage that included renowned rabbis was the 1913 delegation of Rav Aharon Walkin and Rabbi Dr. Meir Hildesheimer, who were sent to America to raise awareness of the nascent Agudas Yisrael, recently founded in Katowice, Poland. The group followed up with a larger delegation in 1921, led by Rabbi Meir Dan Plotzki, Rabbi Dr. Meir Hildesheimer and Dr. Nathan Birnbaum.

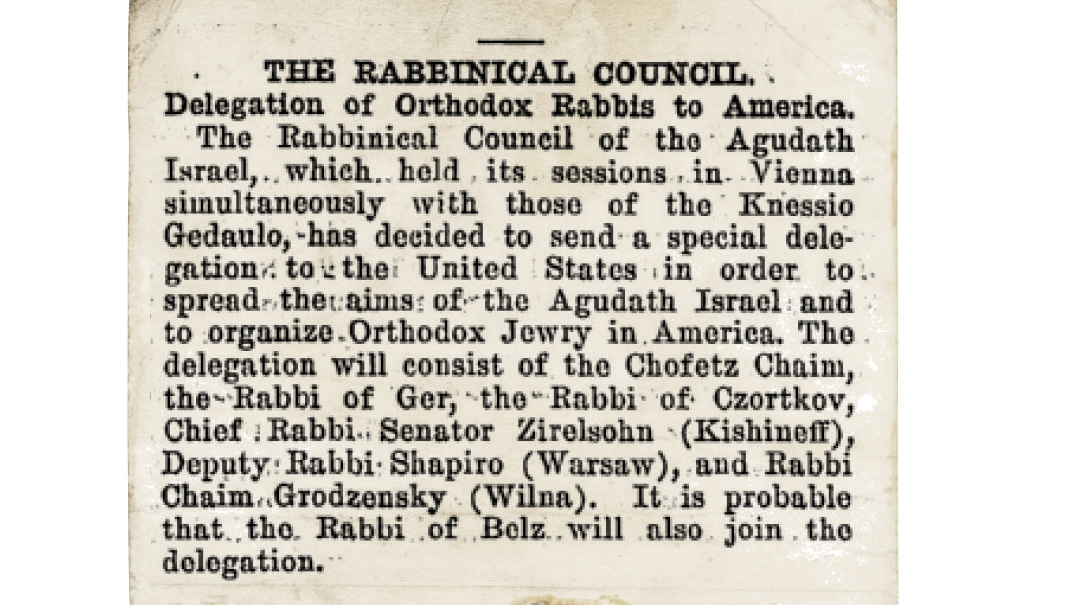

But none of those trips matched the scope of the Central Relief Committee (CRC) delegation in 1924. Initially, it was announced that the delegation would feature the who’s who of Torah leadership at the time, including Rav Chaim Ozer, the Chofetz Chaim, and the rebbes of Belz, Gur, and Chortkov. Ultimately, the selected delegation featured a different group of Torah giants: Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook, Rav Avraham Dov Ber Kahana Shapiro (the Dvar Avraham), and Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, rosh yeshivah of Slabodka.

The Fundraising Dinner at Hotel Walton

They headed to the United States and began their fundraising mission in March 1924. They would spend about eight months in the country, visiting major Jewish cities, delivering shiurim at the handful of yeshivos that existed at the time, speaking at events, and meeting with a cross-section of the American Jewish community.

While they didn’t procure enough funds to reach their goal, they left a long-term impact on the American Torah community. Most of these fundraising trips were abject failures with disappointing results. But with the end of mass migration came a period of stability and development within the American Jewish community. Visiting rabbanim served as beacons of light, bridging the gap between the old world and the new. These rabbinical fundraisers allowed the Americans to learn from Torah giants and benefit from their proximity while also giving them the chance to support Torah learning.

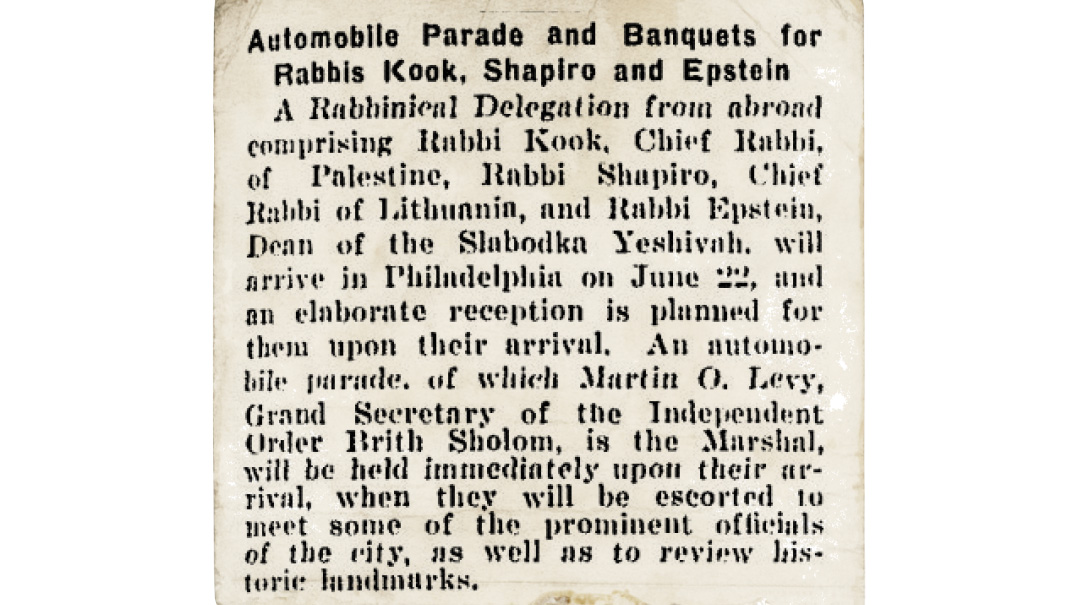

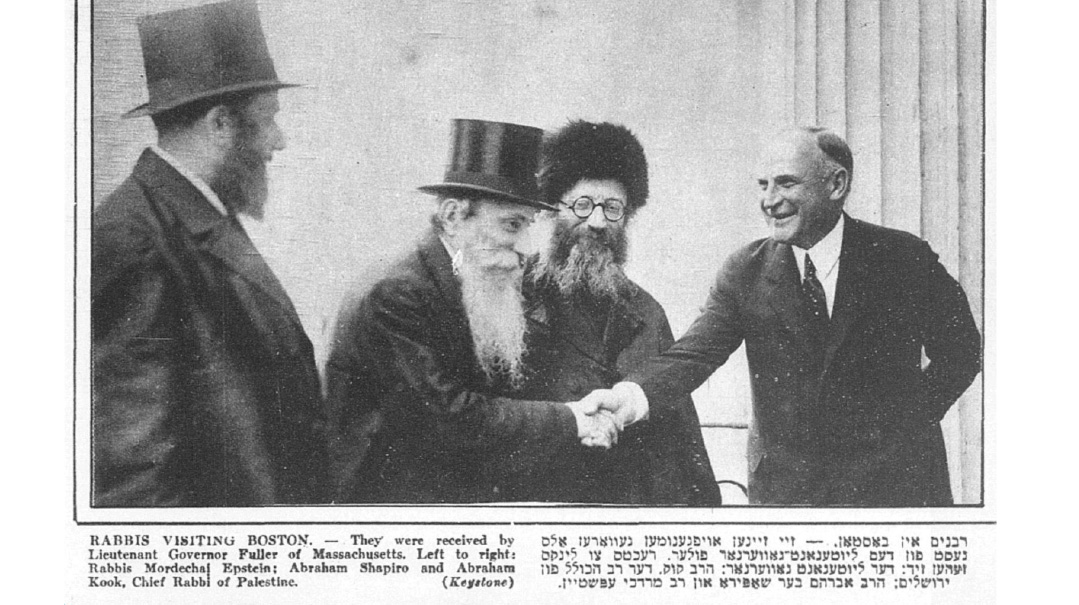

This fundraising mission was even more significant than any that came before it. The prominence of the guests — Rav Kook was the chief rabbi of Palestine and a renowned orator and author, the Dvar Avraham was the most respected rabbi in Lithuania, and Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein was the head of the famed Slabodka yeshivah — evoked a Jewish pride among the masses of American Jewry. Multitudes turned out to greet them at railroad stations, automobile processions, hotel receptions, banquet fundraisers, shul and yeshivah lectures, and other public forums.

Despite the fanfare, the throngs of well-wishers, and the extensive press coverage in both the Yiddish and general press, the CRC failed to hit their fundraising target of one million dollars. Only $300,000 was raised over months of fundraising. But by other measures, the visit was an everlasting success. It generated an atmosphere of kavod haTorah, as a large number of American Jews proudly and publicly identified with these traditional rabbis who represented Torah, its institutions, and ideals. Sadly, for some, it was an opportunity to bring their children and grandchildren to glimpse the “old world rabbis,” whom they believed would soon become extinct.

A highlight of the trip occurred after Shavuos, when the trio visited Philadelphia, home to America’s third-largest Jewish population after New York and Chicago. The rabbanim visited Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where Rav Kook delivered remarks regarding liberty, freedom, and the shared destiny of America and the Jewish People. They then went on an outing on the yacht of Philadelphia mayor W. Freeland Kendrick, and attended a massive fundraising dinner at the Hotel Walton.

A vivid account of the day was presented later that week in Philadelphia’s Yiddishe Velt newspaper:

The Jewish quarters of the city were decorated with flags, American and Jewish. Throughout the day, automobiles decorated with flags could be seen everywhere. At 10 o’clock, everything was ready for their arrival. The Reception Committee had arrived at the Brith Sholom building, and there formed the lead of the automobile parade. Long before 11 a.m., the hour scheduled for the arrival of the delegation, Rabbis Kook, Shapiro, and Epstein, crowds had assembled at the North Philadelphia station. It was a crowd curious, alert, and ready to worship.

A little flurry was caused when the train on which they were due pulled in and the Rabbis could not be discovered. After five minutes, however, they appeared, and the enthusiasm of the throng held in abeyance had full opportunity to give vent to itself. As they were let loose into a veritable maelstrom of humanity, bent on paying homage to three great Orthodox leaders, sights unusual to American Jewish life portrayed themselves. Men kissed the hands of the Rabbis with the reverence paid to some divine personage. Children were lifted up to be kissed and blessed by the good men of Israel before the car carrying the party was permitted to proceed on its way.

An American city was a strange setting for this mystical homage. The American pomp and parade, a strange background for these Orthodox men. Scholarly looking, all three of them — with their long flowing beards, the kindliness which they radiated, and that absorption in an inner life which their countenances portrayed — they belonged somehow in the peace and quiet of the study rather than in the midst of an American Jewish crowd, hurrying as only American crowds can. But since the Rabbis have been received in other American cities previous to their visit here, the peculiar flavor of the American greeting must by this time be familiar.

The welcome at the station over, the parade turned to Independence Hall, where Mayor Kendrick and Hon. B. W. Golder, chairman of the Reception Committee, awaited them. It was more like some triumphant procession, this automobile parade to the shrine of the American nation. It was Sunday. The day was quiet. Broad Street, the path of the parade, [was] void of its usual hurrying throngs. All was serene. The sun smiled down benevolently, tempering its warmth. And at the head of the procession, led by Martin O. Levy, grand secretary of the Brith Sholom, rode the visitors from the old world, accompanied by the Chief Rabbi of the city, Rabbi B. L. Levinthal, and Mr. Jacob Ginsburg, publisher of the Jewish World.

Four motorcycle police flanked on either side of the car of the delegation formed a guard of honor providing the right of way. A hundred automobiles or more followed in the wake of the car of honor, with flags flying merrily in the breeze. It was a leisurely procession which made its way down Broad Street and [was] in thorough keeping with the spirit of the three men who are our guests of honor for two days.

At Independence Hall it was different. Thousands of people were gathered to catch a glimpse of the Chief Rabbi of Palestine and his distinguished associates, the Chief Rabbi of Lithuania and the Dean of the Slabodka Yeshivah. The arrival was the signal for a prolonged outburst which lasted for several minutes, and for a rush which, for the moment, threatened to overwhelm the Rabbis. There have been larger crowds assembled to pay tribute to some distinguished visitors. This crowd, nevertheless, proved quite up to the mark in enthusiasm.

It was several minutes before the Rabbis could proceed into the hall, where the Mayor awaited them.… He received the Rabbis in the room where the Declaration of Independence was signed.

In a brief address, he welcomed the Rabbis. “In the name of the 2 million citizens whom I have the honor to represent. I take great pleasure in presenting to each of you the key to the city. I sincerely trust that you will carry away with you a kindly opinion. I count among my sincerest friends, to whom I owe a great deal of my success, men like Mr. Ginsburg and others of your people. If there is anything that I can do further, I shall be glad to do so.”

Rabbi Kook answered for the delegation in Hebrew. Mr. Jacob Ginsburg interpreted for the Mayor. Rabbi Kook expressed his deepest appreciation, and that of the whole delegation, for the cordiality of the reception accorded and the honor paid in receiving them in the shrine of the American nation. He expressed the hope that the freedom and equality of all humanity, which the Liberty Bell proclaimed, might continue to prove America’s inspiring message.

It was a short but impressive ceremony when Rabbi Kook placed a wreath of flowers on the Liberty Bell. The flowers, he said, were symbolic: a crown on the Liberty Bell, which in turn was the crown of America. The flowers, he declared, would remain fresh and blooming, providing the spirit of the Liberty Bell remained unsullied. But should the bell lose its traditional meaning, then the wreath of flowers would turn into a wreath of thorns. Mayor Kendrick seemed particularly pleased that the Rabbis, again with Rabbi Kook as their spokesman, learning of his approaching fiftieth birthday, wished him every success and gave him their blessing.

The final touch to a reception of great cordiality, and the most picturesque, perhaps, was the tribute paid to the Rabbis by the Talmud Torah children of the city. Children of every age, from six and upwards, fully 300 of them, keyed up with enthusiasm, with curiosity, and just the happiness of youth, were massed outside of Independence Hall. … Mayor Kendrick attempted to speak, but his voice was lost in the sudden outburst of childish voices lifted in song. First it was “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” then the Jewish national anthem, and then other Jewish songs.

It was their hour, and they were making the most of it. The climax came when a little bit of a boy, who looked not more than eight, was hoisted up on the platform to hand Rabbi Kook a bag of coins as the contribution of the Talmud Torah children to the Yeshivah Fund, in whose interests the Rabbis were in this city. It was not nearly as simple as that. The youngster made his presentation in a long speech in Hebrew. It was a glib recitation, to this unwitting auditor at least, and it seemed to please the Rabbis very much. A parade around the entire platform, so that all might satisfy their curiosity, and the reception at Independence Hall was over.”

Rav Kook standing outside the White House

Strong Support from Silent Cal

In an unprecedented occurrence, these visibly Orthodox rabbis regularly met with mayors of major cities in public receptions where they were often gifted with a symbolic key to the city. On April 15, the rabbinic delegation had an audience with President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. Rav Kook expressed gratitude for presidential support of the Balfour Declaration and relief efforts during the war. The president, in turn, promised that the American government would assist Jews whenever possible.

Future Role of American Jewry

“In an exclusive interview he had with the Morgen Journal, Rav Kook referred to American Jewry as a hidden treasure and enumerated three qualities they had which, if developed, could make them one of the most important Jewries in history. These qualities were a deep feeling for religiosity, a sense of Jewish nationalism, and a sense of social responsibility. He attributed the last quality to the excellent human material of which the Jewish communities consist, as well as to the civil liberties enjoyed by American Jews as free citizens of a republic under a generous and democratic government. He also noted the importance of the civic education that American Jews receive through their unhampered participation in their country’s political affairs. In order for American Jews to develop their potential, Rav Kook said, it is necessary for them to provide a proper Jewish education for their youth. To this end, he felt that parochial schools should be built by the Jewish community. He felt that American Jewry would eventually surpass Jewries in other lands of the diaspora and serve as an example for them, and ultimately, would be able to transfer its talents to Palestine to help rebuild the Jewish homeland. These last remarks echoed those he made at

an OU convention in June (in Far Rockaway), where he said that, just as in the past, there were two great centers of Jewry – Palestine and Babylonia – so today, there are two great centers of Jewry – Palestine and America.” — Joshua Hoffman; Rav Kook’s Mission to America

This article is in honor of the centennial of the historic fundraising mission of Rav Avraham Yitzchak Hakohen Kook, Rav Avraham Dov-Ber Kahana Shapiro of Kovno, and Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein to the United States in 1924.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1015)

Oops! We could not locate your form.