Passport to Life

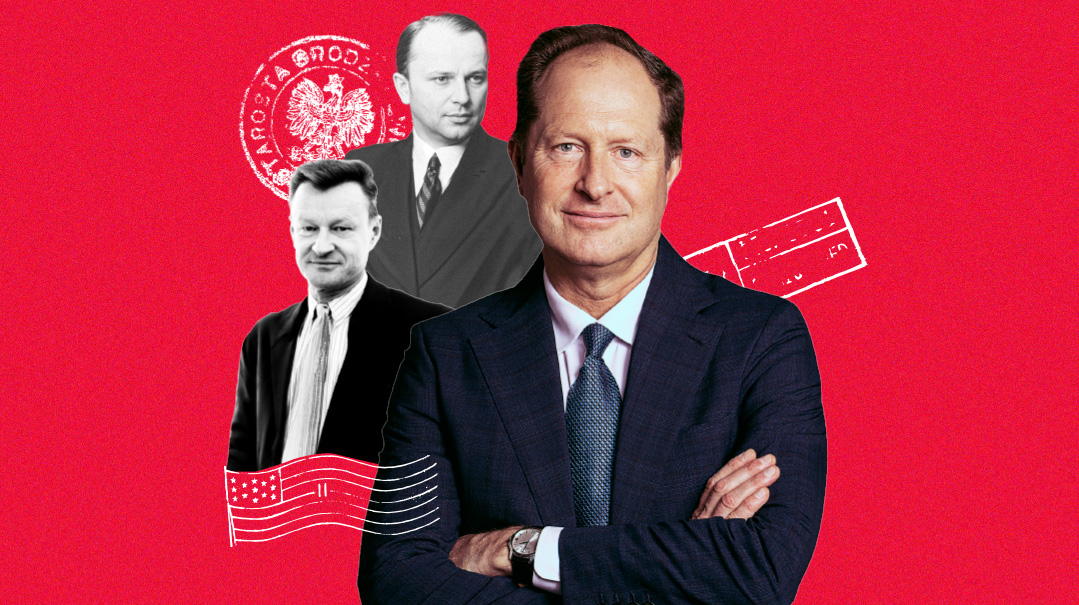

Mark Brzezinski has come full circle as an American ambassador to Poland who never forgets his humanitarian legacy

Photos: GPO, Family archives

IF Washington, DC ever becomes so over-populated that authorities need to weed out who really belongs and who’s an interloper, a one-line test would do the trick. “Pronounce ‘Brzezinski,’ ” it would read.

The formidable Polish name (pronounced bru-zhin-ski) is a Beltway staple. It was introduced to Americans by Zbigniew (known as “Zbig”) Brzezinski, a legendary Poland-born statesman, who served as President Carter’s national security advisor and remained a lion of the foreign policy establishment until his passing in 2017. Zbig’s son Ian is a foreign policy expert who served in a senior position in George W. Bush’s Defense Department. A daughter, Mika, greets Americans every morning as co-host of MSNBC’s Morning Joe. Sundry Brzezinski spouses dot the DC think-tank landscape.

But perhaps it’s Zbig’s second son Mark — serving as American ambassador to Poland since 2022 — who best encapsulates the unlikely story of this Polish-American diplomatic dynasty. That’s because his own career mirrors that of his heroic — now mostly forgotten — grandfather Tadeusz.

A prewar Polish diplomat who risked his own government’s displeasure to assist Jews trying to flee 1930s Germany, and who continued his work in Canada, Tadeusz was stranded in North America after Poland’s dismemberment at the hands of Nazi Germany and the USSR. He raised his family with no money in Montreal, refusing to seek support from the Jews he’d saved. It was Menachem Begin who plucked the elder Brzezinski out of obscurity, thanking Zbig for his father’s actions at a Washington press conference in 1978.

That unique moment in both countries’ history was part of a longer diplomatic process that led to the historic Camp David peace accords between Israel and Egypt that paved the way for the détente with the Arab world that is still unfolding today. The process played out with mutual suspicion between the Carter administration — including National Security Advisor Brzezinski — and the pro-settlement Begin government. As a young boy, Mark witnessed the protagonists — President Jimmy Carter, Begin, and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat — up close.

Decades later, Mark’s service as ambassador to Poland has taken the family full circle, from Polish diplomat in North America to American envoy to Warsaw, and says that he constantly recalls the lessons of his grandfather Tadeusz. “I walk in his shadow and his higher moral calling and I’m conscious of that every day.”

“The Jewish people never forgets a mitzvah”, Begin told Brzezinzki. (Picture right to left) Zbig Brzezinski, Menachem Begin and Begin’s chief of staff Yechiel Kadishai

Higher Calling

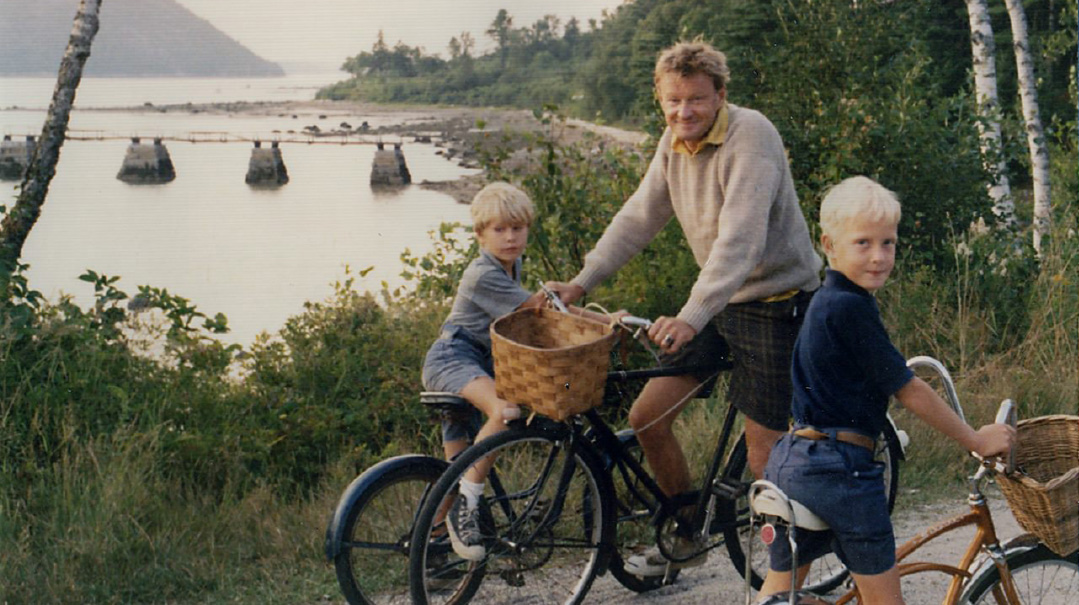

Two things impressed a young Mark Brzezinski about his grandfather Tadeusz, while visiting his grandparents in Montreal in the ’60s and ’70s.

“My grandfather didn’t speak any English, and so my sister, my brother, and I would talk to him in a kind of sign language,” he recalls. “And he was the most kind, thoughtful, generous, and naturally warm person, despite having gone through such tremendous upheaval.”

Even for a diplomat, used to a nomadic lifestyle, Tadeusz’s life was one of turmoil. By the time his American-born grandchildren visited him in Montreal in the 1960s and ’70s, the patriarch of the Brzezinski clan was a far cry from the patrician, successful diplomat he’d been in the 1930s.

Born in 1896 into an upper-class Polish Catholic family, he joined the diplomatic corps of the new Polish Republic in 1920. His career was to span almost the entire life of the ill-fated republic, which was crushed by the German blitzkrieg in 1939.

Joined by his wife Leonia, Tadeusz served in Essen, Germany; Lille, France; Leipzig, Germany; Kharkov, in Soviet Ukraine; and finally, Montreal, where he lived in limbo until the postwar Communist takeover of Poland made clear that for the Brzezinskis there was no future back in their homeland.

It was his posting to Germany in 1931 that earned Tadeusz his place in history not just as father of an American statesman but as a hero in his own right. “We have a picture of him as consul general in Leipzig, wearing a top hat at a ceremony for diplomats, where the group is greeted by Hitler. That picture makes my grandfather’s story very, very real, because there’s this monster of all monsters, and near him is standing my grandfather.”

Very soon after President Hindenburg made Hitler chancellor of Germany in January 1933, the first chill winds of the Holocaust began to blow. Living in Leipzig, Germany, the Brzezinskis were witness to the first effects of Hitlerism in the country. Born in 1928, Zbig Brzezinski remembered the torchlit rallies that the Nazis staged. “I understood more and more that my father was saving Jews, going further than official Polish policy,” he recalled in a 2010 interview.

Almost immediately, Germany’s new bosses began making trouble for Polish emigres — Jews and non-Jews alike who were living in the country. Leipzig contained a community of Ostjuden — Jews who’d fled Poland during the upheavals of World War I but had never attained German citizenship. As happened at the onset of the Holocaust, the Nazis threatened to expel them to Poland, but Poland, deep in a resurgence of its own official anti-Semitism, didn’t want its Jews back. They were left effectively stateless, and with no identity papers, couldn’t move on to a third country, either.

That’s when the local Polish consul, Tadeusz Brzezinski, stepped in. He issued identity documents, including Polish passports to hundreds of people enabling them to leave Germany. For many, the Brezinski document proved to be their ticket to life.

Begin and Brzezinski match wits over a chessboard at Camp David watched by members of the Israeli delegation.

On the Run

The paper trail surrounding Consul Brzezinski’s activities is sparse, yet enough to show the extent of his activities. Bill and Friedel Katz, a young engaged couple who’d fled Germany to France after Hitler came to power, were spared the Holocaust because of Tadeusz’s intervention.

In moving testimony to Washington’s Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1991, they described the chain of events that the Polish diplomat was a part of. Bill had been a young Jewish editor at Die Welt am Montag, a leading liberal — and anti-Nazi — weekly. Friedel was a law student when Hitler came to power. Both fled to Lyon, France where they met. By now stateless, when they wanted to marry, they discovered that without papers, the French state wouldn’t recognize their marriage.

“My future husband wrote to his father, who was still in Germany, to ask him for help,” said Friedel Katz. “His father went to Leipzig, to see the Polish consul general Brzezinski, who provided him with two Polish passports, one for me and one for H. W. Katz. These passports allowed us to get married.”

The precious passports went much further, though. Bill volunteered for the huge but ramshackle French army, which rapidly collapsed in the face of the German assault, and his regiment retreated southwards toward the Spanish border. Friedel, by then a mother and living in Paris, took her baby girl and fled southward too, to escape the German onslaught on the French capital.

“My Polish passport saved my life more than once, when I had to flee Paris,” she said. “For a refugee, as you know, a passport is a lifesaver.”

Reunited with her husband in Marseille, the couple were able to cross the border into Spain and then Portugal, and then sail for America, and life — all because of a Polish consul to Leipzig whom they’d never met.

Begin and President Carter

Time of Need

Refusing to stand by while others suffered landed Tadeusz in hot water with the Polish and German authorities.

“He got criticized by his Foreign Ministry superiors,” says Mark Brzezinski. “When I visited Leipzig, I was shown documents of the Nazis complaining to Poland about my grandfather’s rescue activities.”

For a junior Polish diplomat to poke his nose into the internal affairs of a rising Nazi Germany was a risk, at least on the professional level. What persuaded him to join the likes of far better-known diplomatic rescuers like Japan’s Chiune Sugihara and Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg, who used their diplomatic standing to save Jews?

“I would speculate that it was a basic sense of humanity, that there are these people who have terror in their eyes, and I’ve got to do something for them,” says Mark Brzezinski. “It wasn’t more than that, and it wasn’t just Jews — it was also Poles living in the Leipzig area who were having their passports taken away by the Nazis.”

Philo-Semitism surely played a part, though. Tadeusz’s son Zbigniew told of the time that his father had intervened to prevent Polish anti-Semites from roughing up a Jew, using his cane to beat them.

Whatever moral or religious convictions were at work, they propelled Tadeusz Brzezinski into the same rescue operations across the Atlantic. In 1938, after a posting in Kharkiv, Soviet Ukraine, he was dispatched to Montreal as consul general. With the Canadian government enforcing a near-total ban on Jewish refugees, he tried to bring in Jews from Japan, in order to free up permits for others to leave Europe and head to Japan in their place. The struggle and the paltry results are chronicled in None Is Too Many, a book about Canada’s hardline policies during the Holocaust.

The German invasion of Poland in 1939 meant that the country that Tadeusz Brzezsinki represented no longer existed. His consulship continued in attenuated form during the war years as he represented the Polish government-in-exile. But the death knell for his diplomatic career sounded when the USSR swallowed Poland and the “London Poles” were thrown under a bus in the postwar carve-up that reduced Europe to Communist and capitalist blocs.

The Communist takeover meant that the former diplomat was now unemployed. “My grandfather sold insurance door to door in Canada for the rest of his life, and wasn’t very successful,” says Mark Brzezinski. “And my grandmother — I don’t know how to say this — had a different outlook. She said, ‘You know, Tadeusz, why don’t you go to the people who you helped, and ask them for help?’ And he refused to do that. ‘What I did, you don’t go ask for payment for,’ he said.” So finances were a big problem in my dad’s parents’ family.”

A young Mark Brzezinski spends time with his father Zbig,

Poles Apart

Somewhere in the upper reaches of the American foreign policy pantheon, peopled by icons like Henry Kissinger, his successor as national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, has a place of honor. How the young Polish refugee rose to such heights is a story similar to Kissinger’s — one of talent, iron will, and the American Dream.

“In the beginning, my father thought that his name would hold him back in America, but he realized that he could do something in American political life, when a young man whose name was Heinrich — later, Henry — Kissinger became national security advisor and secretary of state.”

Like Kissinger, Brzezinski had an acerbic wit and a love for geopolitics. His son Ian Brzezinski recalled the time that the government of Lithuania treated him to a boar hunt. He shot two boars and then named them Molotov and Ribbentrop.

Kissinger and Brzezinski were very different. Jew and Catholic, Republican and Democrat, advocate of détente with the USSR, and aggressive anti-Communist — they were two very big characters with two different worldviews. They were also rivals for the same university chair; when Kissinger got a coveted position at Harvard, Brzezinski, who’d missed out, left for Columbia.

But Mark Brzezinski rejects the contention that they didn’t get along. “Some people say that they didn’t like each other. Nothing could be further from the truth. I have a copy of Henry Kissinger’s book about China, inscribed: ‘To Zbig Brzezinski, who traveled a parallel road, with distinction from his friend’ — and then he added in parentheses — ‘we’ll keep that secret, Henry Kissinger.’ ”

The Bavaria-born Kissinger became the more iconic of the statesmen, but Brzezinski presided over American foreign policy at some of its most dramatic moments of the second half of the 20th century. One — the Camp David peace deal between Israel and Egypt — dramatically altered Israel’s strategic environment. It removed the threat of war with the Arab world’s biggest power, and opened the way for peace with Jordan, and arguably the recent Abraham Accords.

As that process got underway, initial meetings between President Carter’s national security team and Prime Minister Begin in 1978 turned frosty over the issue of Israel building in Yehudah and Shomron. Throughout his life, Brzezinski remained a supporter of Israel, albeit sometimes a harsh critic in the Obama mold. As the negotiations unfolded, he was accused by Israel’s supporters of harboring ill will toward the country, said to be rooted in his Polish Catholic background.

But according to Shlomo Avineri, a Polish-born Israeli political scientist and former director-general of Israel’s Foreign Ministry who passed away last year, the anti-Semitism allegations were nonsense. The friction, he said, emanated from his detached, clinical attitude to the country that often draws heartfelt support from Americans. “He felt nothing of the special empathy that American politicians often have for Israel.”

All of that meant that when Menachem Begin met Zbigniew Brzezinski, it was a clash of worlds. Ahead of the meeting, writes Yehuda Avner, a Begin aide, in his classic fly-on-the-wall account The Prime Ministers, there was intense curiosity as to the nature of their interlocutor.

“All of us on the prime minister’s staff were curious to know if there might be some sort of cultural affinity, some natural rapport between him and Begin, both of them being of Polish origin.”

Those expectations were disappointed. “Poles apart,” quipped Begin’s chief of staff, the irreverent Yechiel Kadishai.

But according to Mark Brzezinski, that remark is inaccurate: There was mutual respect, despite the differences. “They were at very different points in terms of the West Bank and the settlements, but underneath there was an affinity. They both came from occupied Poland, and they were both in their own ways, warriors.

“Begin was a real warrior, but my father had polio when he was little. And he was an intellectual warrior. His half-brother, George, was an actual warrior in the Polish division of the Canadian Army, and my father always had tremendous respect for people who were warriors, and who would stand their ground. And that was the two of them. Two tough guys from Poland, each tough in their own way.”

Hearts and Minds

Be that as it may, Menachem Begin sought a way to the heart of Carter’s top aide, and he found it in Tadeusz Brzezinski’s story. Arriving at Blair House, the president’s official guest residence, for breakfast, Zbig Brzezinski was surprised to find that Begin had invited the press corps.

Holding up a file, he told the reporters that the contents were a dossier on the national security advisor’s father Tadeusz’s Holocaust rescue activity that were found in an archive in Jerusalem.

“The Jewish People never forgets a mitzvah,” Begin told his guest.

Shlomo Avineri was partially responsible for the dossier. Two years before, he’d met Brzezinski in Washington, and at the end of their meeting, Zbig turned to him with a strange question: “What is Keren Kayemet L’Yisrael?” he asked in his Polish-American accent.

It turned out that in gratitude for the help that Tadeusz had rendered them in the 1930s, the Leipzig Jews had made a donation to Israel’s Jewish National Fund in his honor. Back in Jerusalem, Shlomo Avineri procured a copy of the original: JNF records showed that the Polish Jewish community of Leipzig contributed £45 to inscribe Consul Brzezinski in the organization’s “Golden Book.”

Visiting Israel later in July 1976 as foreign policy advisor to the Carter presidential campaign, Brzezinski arrived in the tense week of the Entebbe kidnapping. On the evening before the rescue, he joined then-defense minister Shimon Peres for dinner and asked why no military rescue effort had been mounted. Peres had to coolly deflect him, aware that the commandos were gearing up for the top-secret rescue attempt.

At the end of the crisis, Brzezinski spoke of the remarkable national solidarity he’d seen over the course of the week. “I was deeply impressed by how the whole country virtually stopped breathing in solidarity with the hijacked victims,” he said.

Against that background, Brzezinski — normally an unemotional, even tough man — was unusually moved by the recognition of his father’s rescue work, especially given the insinuations in the media of his anti-Israel positions.

“I cannot but express to you, Mr. Prime Minister,” he said, “my admiration for the degree to which you live the suffering of your people, and yet are also the personification of the triumph of Israel.”

Turning Back the Clock

As a young teen, Mark Brzezinski saw the Camp David process play out before his eyes, including moments of camaraderie between the two Poles — Begin and Brzezinski — such as in the iconic photo of the two playing a game of chess at Camp David. Today’s American ambassador to Poland was at the signing of the Israel-Egypt peace treaty in 1979, in what was a high point for the Carter administration. “I remember talking to Menachem Begin, and him saying that ‘my fellow Pole is Zbig Brzezinski,’ and that the two of them were able to have secret conversations in Polish.”

With such a heritage, it wasn’t surprising that after a career in law, he headed to diplomacy. “When I was in law school, the Berlin Wall came down, and I spent a summer in Poland. I thought to myself that I could probably do more by focusing on this part of the world than I could do as a federal prosecutor.”

Dispatched by President Obama to be ambassador to Sweden in 2011, he focused on Raoul Wallenberg’s work on anti-Semitism. “I made the narrative of Raoul Wallenberg very much a focal point of my four years as US ambassador to Sweden, because Raoul Wallenberg more than anyone gives life to the theme of not being indifferent.”

For the legendary Swedish diplomat and Holocaust rescuer’s 100th birthday in 2012, Brzezinski arranged for President Obama to visit Stockholm’s Great Synagogue and meet Wallenberg’s still-living half-sister and survivors who were saved by him. He also used the US embassy’s bully pulpit to intervene when the mayor of Malmö, a Swedish city with rampant anti-Israel hatred, said that the local Jews were responsible for anti-Semitism.

Just two days after Brzezinski presented his credentials as ambassador to Poland’s president in February 2022, Russia launched its attack on neighboring Ukraine. With Poland a rising pro-Western power in Eastern Europe, and a prime conduit for American arms to Kyiv, that has made the mission to Warsaw a high-profile one.

For Ambassador Brzezinski, his father and grandfather’s career-long suspicion of Russian power has become relevant once again as Moscow tries to turn back the clock. “It’s a collision between dictatorship and democracy,” he says simply of the Russian revanchism.

Coming from Mark Brzezinski, a humanitarian call isn’t just diplomatic boilerplate, but family history. It’s the heritage of a man whose grandfather ignored protocol to do everything he could for human beings he didn’t know.

“For me it’s so meaningful that I can be here as US ambassador,” says the diplomat whose career completes a family circle, “in the shadow of a diplomat who risked his career to give passports for life.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1015)

Oops! We could not locate your form.