Out of the Woods

A hiker’s nightmare becomes Search and Rescue’s midnight challenge

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

The alert went out on a rainy, windy night in the fall of 2020:

November 1, 5:41 p.m. We have an activation for a lost hiker with no communication. Please respond to Kakiat Park parking lot for staging.

Information was spotty. The hiker had sent a picture of his location on Google Maps to a friend, along with a distressing message: I’m lost in Kakiat, and my phone’s about to die. I’m going to keep moving to prevent hypothermia.

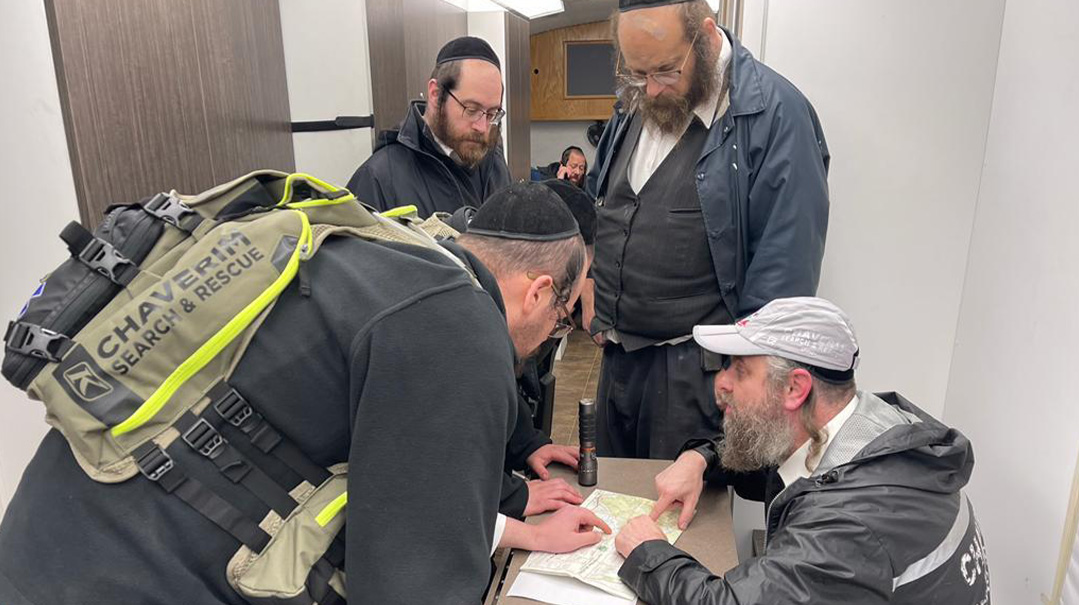

The Google Maps picture didn’t show much — just water lines, elevations, and a dot indicating the hiker’s location. The tough job of trying to pinpoint that location belonged to Chaverim of Rockland’s Search and Rescue coordinator Moshe Jacobowitz, and he got to work downloading park terrain maps and searching for an area that matched the information on the picture. And then he found it, sharing with his team: “The hiker’s last known location is somewhere between Raccoon Brook Hill Mountain and Cobus Mountain, not too far from the Pine Meadow Lake Trail.” The hiker was off-trail and moving. It was like looking for an ant on a pitch-black, rainy football field — but at least they had a starting point.

The amount of time that elapsed since the hiker texted allowed Jacobowitz, owner of a waste management company, to create a circumference within which the hiker would almost certainly be located, and five search and rescue teams were dispatched throughout that area.

For all the high tech equipment employed on the back end of a search, finding a person almost always comes down to a $3 whistle or vocal cords: whistle or scream, listen for a response, advance for two minutes, and repeat.

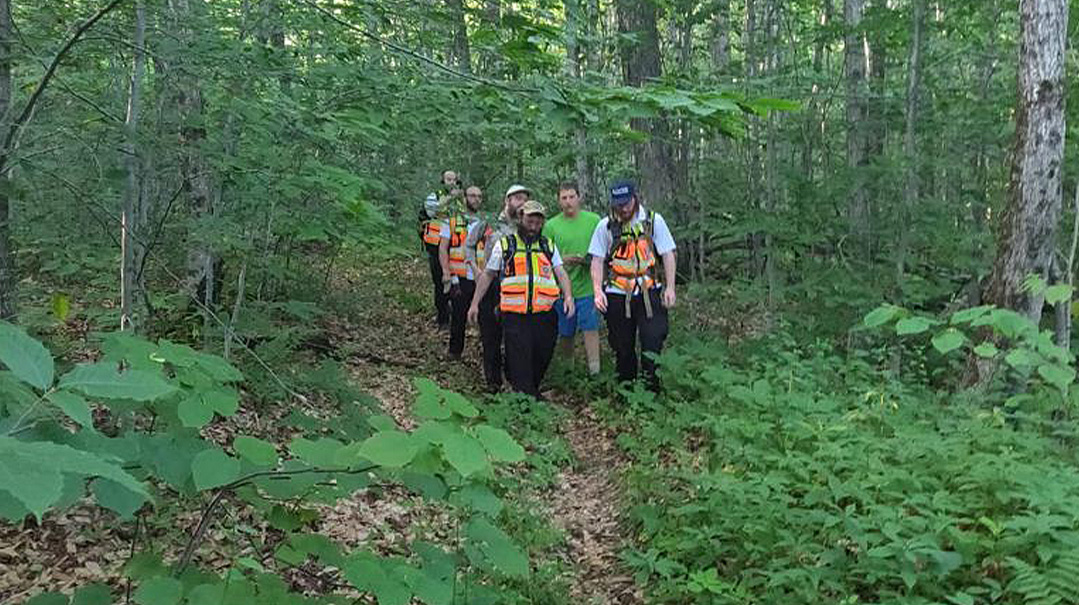

Nosson Kuznicki, a property management director for assisted living communities, and a founding member of Chaverim Search and Rescue (SAR), was there that night. “About 40 minutes in, my partner and I saw a light, far in the distance,” he recalls. “I immediately asked the command center if any other teams were nearby — maybe the light was theirs. They answered in the negative, and to confirm, I sent out our in-house whistle code — one long blast is responded to with a few short blasts in a row. The short blasts never came, but a minute later we heard one long whistle blast back. My heart started racing — someone was out there. We continued using whistles to find our way toward each other, and soon the light grew closer. We began calling his name, and then suddenly there he was, scrambling toward us. He grabbed us in a bear hug and repeated emotionally, ‘Wow, chasdei Hashem! Chasdei Hashem!’ And then he added, ‘I need to join you guys!’”

After the longest, darkest, and most terrifying two- and-a-half hours of his life, the hiker, himself a Hatzolah member, was found nearly a mile and a half from his last known location.

Trail Blazer

It was 1991, and 21-year-old Shaya Erps was riffling through a camping catalogue, looking for information on what to do when sprayed by a skunk. On a whim, the chassidish yeshivah bochur decided to order a pack of picture cards labeled “wild edibles,” featuring vegetation found in the wild on which a person can survive.

That pack of cards helped chart the course of his life, as his interest in all areas of wilderness survival took on a life of its own. “I became driven to know everything — how to build a shelter, how to construct survival weapons like bows and arrows, how make a fire without matches, as well as navigation, protection from animals, and so much more,” says Rabbi Erps, Chaverim of Rockland founder and longtime pre-1A rebbi in Yeshiva of Spring Valley, who also teaches science and wilderness survival skills to sixth-grade boys, and survival, first aid, and public speaking to 12th graders.

“Over the years I’ve interviewed dozens of people who survived alone in the wilderness, making use of the land to be self-sufficient, and I’ve read countless books. Each time I learn something new, I head into the woods and put it into practice. And 30 years on, I’m still learning.”

Ever community conscious, in 1999, Rabbi Erps founded Chaverim of Rockland, a volunteer emergency service organization. If you were locked out of your car, or needed a cable boost, or your toddler disappeared out the front door, his volunteers were there in a jiffy. But wilderness wasn’t on the service list, until one harrowing night in 2002.

“A Zeidy and his grandson went into the woods and never came out,” recalls Moshe Jacobowitz. “The family called us, frantic, and we called law enforcement, who put us in touch with New York State Park Rangers. Their response: ‘If they don’t come out by the morning, we’ll go look for them.’ The family kept us on the phone through the night, begging us to do something, but we were just as helpless as they were. In the end, grandfather and grandson emerged the next morning, having made the wise decision to spend the night in a shelter rather than trying to find the way in the dark. But our inability to help that anguished family made it clear to us that we needed to create our own team.”

The learning curve was steep. One night in the very beginning, Rabbi Erps recalls, a crew of well-meaning but untrained Chaverim members gathered in the Pathmark parking lot. A hiker was missing and they wanted to help.

“I knew my guys weren’t trained for this, but I wanted to see if it was really so bad,” he says. “So I went over to a guy holding a shopping bag, and asked what was in it. The bag was filled with heavy D batteries, ‘so my flashlight can last the entire night,’ he told me. Not only would he exhaust himself with that load, but he hadn’t thought of bringing water or first aid essentials. I realized at that moment that for this to work, we needed to go professional.”

Over the past 20 years, the group has grown from a ragtag crew of well-meaning volunteers to a highly trained, sophisticated team that coordinates with law enforcement up to the state level, has participated in searches from Vermont to Virginia, and has a perfect track record of finding hikers who want to be found.

All’s Not Lost

Chaverim of Rockland Search and Rescue (SAR) is a specialized team within Chaverim of Rockland. All 65 members, aged 22 to 47, live in Monsey. They have a designated ringtone on their phone so they don’t miss phone tree alerts, such as “Family of four lost for eight hours, manpower needed, meet in the parking lot of Pine Meadow Trail.”

When Nosson Kuznicki hears the special ring tone, he says his first thought is, “Someone needs us, I’d better run.” Next, he asks his wife. “I’ll probably be gone for many hours so I always check with her first, and she always tells me to go. Calls tend to come in at the end of the day, and sometimes I’m exhausted, haven’t yet eaten, and think there’s no way I’ll have the strength to hike for hours. But adrenaline kicks in every time.”

He checks the weather and puts on hiking boots. Sweatshirt and hat are in his car. He grabs his headlamp and camelback knapsack, which holds three water bottles, a first aid kit, ice and heat packs, and 100 feet of rope for splinting or making a stretcher. He throws in a bite for the car, and is on his way.

Kuznicki arrives at the mobile command center, a refurbished old bus. This office on wheels is driven to a parking lot near the search area, and serves as the nerve center of operations. Through the door on the left is a conference room with a table, chairs, computers, and phones — this room is used to coordinate with other agencies, debrief family members, and to make search plans. Through the door on the right is a communications room with five fully equipped work stations, computers with high-speed Internet, fax, printer, two-way radios, and other office equipment. The fellows at the work stations are busy tracking and directing each team via the satellite trackers they carry. A map of the entire search area is projected onto a huge screen, and team members appear as blips of moving light. The only way to communicate is by text, with communiques such as, “Team 6, you’re veering off trail, head over to the left,” or “Yarmulke found at coordinates 4.16606°N, 74.17914° W. Teams 2, 3 and 7 divert east via Cone Trail.”

Plans are being made with whatever information is available. Is there a last known location? What time did the hiker set out? Is the hiker on a trail or off, and does he or she have cell service? Is the party injured? If the hiker is in communication with the command center, they are generally told to stay put and prompted to recall landmarks they’d passed. Did you pass a stream? A bridge? A shelter? Was it on your left or right? How many minutes ago?

“Most people in the woods just see mountains and trees, but we see a neighborhood with streets, avenues, and cul-de-sacs. Power lines, streams, lakes, gullies, and bridges form our street map,” explains Yossi Margareten, a founding member of Chaverim SAR and coordinator of the entire Chaverim of Rockland, who works for the Office of Emergency Preparations for the Town of Ramapo. Coordinates of the last known location are identified and pinned on a digital terrain map. Factor in the time that has elapsed since the hiker was at that location, and the search can be narrowed to a tighter locus. Routes are planned; if the hiker’s location is known, the most direct route there is often off-trail, and a terrain map is used for them to chart their own path.

Teams are formed by balancing strengths: A good map reader, an EMT and a fast hiker would be an ideal mix. Each team has a designated communicator, who is in contact with the command center, a navigator, and a sweeper, who stays in the back to make sure no one is left behind. Depending on the circumstances of the search, between two and seven teams are deployed, with three to four men per team.

The team owns a collection of ATVs, but they’ve learned that when it comes to the woods, hoofing it is the quickest way forward. The tree canopy severely limits the value of photography drones in a search, but they’re hoping to acquire a drone that uses infrared technology to home in on humans. They’ve recently added a specialized, made-for-the-woods stretcher — extremely lightweight, and with superior shock absorption — to their stock. Regarding search dogs, which the team has used on occasion, despite their reputation, the canines haven’t led the team to a lost hiker even once.

Jacobowitz relates the case of four exhausted 19-year-old boys who had been hiking in Catamount Mountain off Route 202 in Rockland County for five hours and decided to leave the trail and follow a wooded road that ran downhill, assuming it would be a shortcut out of the woods. Instead, they wound up at the top of a cliff.

“They didn’t have the strength to backtrack to their trail and complete the hike, plus it was getting dark. Feeling desperate, they called us. We asked them to describe what they saw, and they told us they were near a power line (the “shortcut” they took was an ATV road used to access the power line). There were three power lines in the area, and we sent teams to areas where these power lines crossed over cliffs. Team 1 shined a light on from the mountain they were on, but the boys said they didn’t see it. Team 2 shined a light from their mountain, and the boys saw it. The team then separated and shined three separate lights, and the boys saw all three, confirming that it was our lights they were seeing — and 25 minutes later, they were out of the woods.”

If there is no communication with the hiker, then his car is the last known location, and all trails in the broader area must be covered. One Erev Yom Tov, a call came in close to the zeman.

“A father took three of his kids on a hike late in the afternoon, so his wife could finish cooking,” Kuznicki relates. “All she knew was he went somewhere ‘close by.’ The first step was finding his car, and regular Chaverim members combed trailhead parking lots, starting with those closest to Monsey, where he lived. When his car was found, he had already been gone for three hours, so we calculated how much ground he could have covered, in every direction from the parking lot, and constructed a circle of area we knew he must be in. Teams were dropped off at strategic roadside locations to get into that circle from different points. We finally found them a few hours into Yom Tov.”

Waiting for Salvation

Being in the woods at night is like sitting in a bottle of black ink, say team members.

“Everyone is scared the first time — you’re convinced there’s a bear or coyote a foot away from you, and you just can’t see it. But even though we can’t see them, animals sense humans and generally know to stay away,” says Kuznicki. “Night training breaks that fear. We enter the woods before sundown and hike as the sun fades, so we slowly adjust to the darkness. We don’t turn on our headlamps until it’s pitch black, so that we’re forced to keep our eyes trained on the ground to avoid falling, and that intense focus crowds out any other scary thoughts. We also talk to each other to drown out strange noises. After doing this multiple times, one gets to the point of being able to enter the woods at night, alone, without fear.”

On the trail, the mood is focused and serious. Talk is limited to the needs of the search. The pace is brisk, but no one runs — energy needs to be conserved, and a fallen, injured team member would be an unwelcome impediment.

If the hiker has been off-trail for a long time, or if the search teams have covered all the trails in the area without success, more intense tactics are called for.

“Grid searches are tedious and require a lot of manpower, and we don’t do them often,” Kuznicki says. “You calculate the area you believe the hiker is in and comb through it methodically, in order to lay eyes on every foot of woods. Searchers are positioned every X number of feet, all walking at the same pace to ensure they’re walking in a straight line and not veering off course.”

Margareten recalls the 15-year-old nonverbal boy with Down Syndrome who wandered away from his campsite in the Catskills. “The call came in at 2 a.m., and he had already been lost for five or six hours, in an area of the woods with no trails. Since it was doubtful that he’d respond to our whistling or calling his name, we had to do a grid search.”

Teams were deployed to the furthest areas the boy could have reached, in every direction, and each team combed its designated area in a grid-like fashion. The teams slowly converged toward each other. At one point a hat with his name on it was found in a creek, and they were able to narrow the search.

“One searcher’s area of the grid included a private dirt road that led to a few houses in the woods,” Margareten says. “He found the kid sitting on the road, exhausted, having been lost for 17 hours. Park rangers had been within 1200 feet of him, calling his name, but he hadn’t responded because he was nonverbal.”

Kuznicki brings us into the headspace of a lost hiker. “Imagine yourself sitting on rocky ground, propped against a tree amid a sea of endless trees. It’s been five hours, and your back and limbs are in agony. You’re shivering with cold and desperate for a drink. And all that’s nothing compared to the terror of watching the woods grow dark, the sounds of the night awakening around you.

“And then you hear a guttural noise. Is that an animal? You hear it again….and then you think you hear your name. I must be imagining it. But then you hear your name again, unmistakable this time. This is it, it’s over. Oh my gosh, oh my gosh, oh my gosh. You scream back, and then see a light, followed a minute later by three strapping men.

“At this point, many hikers start screaming, and some dance around in circles, giddy with relief,” Kuznicki says. “And then the praises flow: ‘You guys saved my life, I never could have imagined there’s a group like this, mi k’amcha Yisrael…’ and then an embarrassed, ‘I can’t believe this actually happened to me, I feel terrible to have bothered you like this!’ The relief is indescribable — and even more so for those who’ve had no communication with the outside world since becoming lost.”

Still, they’re not out of the woods until they’re out of the woods — which often requires hiking off-trail in the dark — but there’s an underlying current of euphoria as well.

Staying Skilled

Back in 2004, when Margareten was at the helm of a fledgling team, he reached out to New York State Park Rangers for wilderness search and rescue training. Twenty Chaverim members took the classroom and field course, and the group continued to train, not just in search techniques, but in all aspects of wilderness survival — because anyone on a search and rescue team is at risk for becoming lost himself.

“The more we experienced the woods, the more professional we became,” Margareten says. “One icy winter night we used the 200-acre property of a team member’s relative, and Rabbi Erps taught us how to navigate using the moon and stars. A few members had to be treated for hypothermia, but that, too, was part of the learning experience.”

Rabbi Erps recalls a survival training session one freezing winter night. “We had been walking for hours, in 16-degree weather. I was busy pointing out which plants were edible, how to identify different animal tracks, and what to do if someone falls into a stream, when suddenly one guy says, ‘My feet are frozen, I can’t walk.’ I looked down and saw a pair of dress shoes. We built a fire and brought his feet back to life. Now, each time he’s on a search, he thinks, I had a whole team to help save my feet. This lost individual has no team to help him out of trouble, we gotta find him quick. He’s become one of our most devoted volunteers, and this thought is what propels him forward.”

The team heads into the woods weekly for practice runs, and before each hiking season (when calls average at least once a week), they take a series of 15 training sessions to brush up on dozens of skills, from building shelters, fires and rope stretchers, to stabilizing and evacuating injured hikers. In 2021, many members completed a six month course in Wilderness First Aid.

“We rescued a woman who fell and had a shoulder injury,” Kuznicki says. “We had to evacuate her by stretcher via a complicated route that involved crossing over streams, while keeping her shoulder stabilized the whole time. The surgeon later commented that whoever splinted her shoulder had done a great job, and prevented a much more severe outcome.”

In the beginning, the team relied on law enforcement to run searches, but today, they assess the situation themselves and decide if it’s something they can handle on their own or if they should call in backup. And conversely, the police will reach out to Chaverim Search and Rescue when they need extra manpower as well.

“We’ve built incredible relationships,” Margareten says. Ramapo Chief of Police Martin Reilly agrees, noting how focusing together and combining resources gets the job done. “Chaverim Search and Rescue is a professional organization,” he says, “Coordinating with them is a smooth, positive experience.”

For example, if a hiker is believed to be in danger, upon Chaverim SAR’s request, the police will ping his phone, even if they’re not working on the case. This identifies the phone’s last known location to within 500-1,000 feet. A clue like that can dramatically shorten the search time.

This interorganizational friendship opens doors to helping Jews lost many miles from home, as well.

“In Vermont in 2019, a boys’ camp director called us from the woods in the middle of the night,” Kuznicki recounts. “They were hiking in the Green Mountains, at a massive ski resort with numerous trails, when they realized that a 15-year-old camper hadn’t been seen for hours. To complicate matters, the boy wore hearing aids, and if the batteries died, he wouldn’t hear searchers calling his name. He was wearing a green T-shirt — not too helpful either in the woods. Local authorities were called, but the camp director wasn’t convinced they were making it a priority.

“Entering territory not under our jurisdiction is sensitive, and we couldn’t just barge in. So we woke up our friends in the New York State Police, who reached out to the Vermont authorities on our behalf, and explained the benefit of letting us on board.

“That settled, a bunch of us jumped into cars, aiming to get there for first light. I was in the backseat downloading maps — as nonlocals, we were pretty much going in blind. We calculated the area he could be in — it was huge — and dropped off teams at strategic points. Hours later, we got a call from a group of hikers — the boy had met up with them and used their phone to call his mother, who then called us. We immediately shared the tip with the local police. The hikers agreed to stay with the boy until he was rescued. He was at the far outer reaches of the identified search area, and neither we nor the local police were searching in the area yet. Despite not knowing the lay of the land and needing to download maps to figure out how to reach him, we got to him before the local rangers did. When he saw us, he started dancing. Spending the night alone in the woods will do that.”

What compels these men to drop whatever they’re doing — be it a daf yomi shiur, a relative’s wedding, or sleeping in bed — to head into the freezing night, for an unknown number of hours of grueling physical exertion, over and over again?

“When I answer the calls and I hear the raw fear and panic,” Jacobowitz says. “No one else is coming for them, so how can I not go? And seeing their relief at the moment of contact — there’s nothing in the world like it.”

“Many years ago, before I had any experience, Catskills Hatzolah asked for volunteers to help find a man with Alzheimer’s who wandered into the woods,” Margareten says. “Police choppers were circling overhead, but of course they couldn’t see through dense wood. We found the guy just in time — he was barely conscious, and with Hashem’s help, we saved his life. Another time I went to New Hampshire to help find a vacationer missing in the woods. We were untrained, and by the time we found him it was too late. Events like these have taught me that every minute can mean the difference between life and death, so of course we’re going to run — is there any other choice?”

DAY OF REST?

If you pick apart a search, the number of prohibitions involved on Shabbos is daunting. While calls generally don’t come in on Shabbos, searches on Erev Shabbos often continue into Shabbos.

“Even though we have general psakim for Shabbos, our rav is consulted each time for sh’eilos that pertain to that particular scenario,” says Chaverim SAR’s Yossi Margareten.

Until the missing person is found, Margareten explains, a Shabbos search proceeds exactly as if it’s a weekday, because it’s a safeik pikuach nefesh. If a search seems likely to continue into Shabbos, “Shabbos goyim” (unpaid volunteers) come to the command center and wait until the search ends — ten minutes or ten hours, there’s no way to know — in order to drive everyone home.

When the hiker is found, can the family be notified? “We can’t use the phone at that point,” Margareten says, “but often there’s a family member at the command center. If not, a Shabbos goy drives to their home to share the good news.”

It’s not just the SAR team that can face complex halachic situations. A lost or stranded hiker, too, can encounter scenarios that are off the beaten path. Chaverim of Rockland founder Rabbi Shaya Erps is currently writing a one-of-a-kind halachic guide to wilderness survival called Survival K’halachah. The sh’eilos in the book are as fascinating as they are unusual: If you lose consciousness in the wilderness and are unsure of what day it is when you wake up, when do you observe Shabbos? (On the seventh day after waking up, make Kiddush and Havdalah; avoid chillul Shabbos every day, except for whatever is necessary to stay alive; walking distances is permitted every day). If your tzitzis get stuck on a branch and the strings are torn off and unusable, what can you use to make new strings? (Spider webs, for one). If you’re stuck without food and need to eat protein-rich worms for nourishment, how can you minimize the issur? (Eat half a worm, wait a specified amount of time, and then eat the other half.) How do you avoid bugs that may be in the stream water you’re drinking? (Cover your canteen with a corner of your shirt, and drink through the shirt to filter out bugs.)

Chaverim Search and Rescue’s Moshe Jacobowitz (L) and Yossi Margareten, who to date have a perfect track record, coordinate in the wilderness. “For it to work, we needed to go professional”

IT CAN’T HAPPEN TO ME

Even seasoned hikers can get lost in the woods, but common misconceptions practically beg for trouble:

“I’ll just go a little off the trail to see if I can pick up cell service.” Staying on the trail means you’re not lost, experts say. All trails can be covered systematically by searchers, but off-trail, the woods become endless.

“I have a trail map on my phone, I won’t get lost.” Phone batteries die quicker than you’d expect when in a location that requires a constant search for a signal, especially when using the maps app and flashlight at the same time. Fully charge your phone before hiking, and bring a paper map along. Never enter the woods without letting someone know exactly where you’re heading, and tell them that if they don’t hear from you by a certain time, they should assume you’re lost.

“It’s only 5:00 p.m., it’s a two-hour hike, and sunset isn’t until 8:00 — I have plenty of time.” If you take a wrong turn, you’ll likely end up spending the night in the woods. Start out much earlier than you think you need to.

“I’ll follow that stream — it will bring me to civilization.” Not necessarily. Don’t be enticed to leave the trail.

“As long as I follow my trail color, I’m good.” Careful: Loop hikes often include parts of different trails, and the color will change accordingly. Know the colors you need to complete the loop, and be on the lookout for the next color you need.

DARKEST BEFORE THE DAWN

As we parked the car and found the trailhead that day in June, all seemed routine in the universe my sister and I created for ourselves in the spring of 2020: a hiking club of two, the perfect antidote to all things Covid. We hiked frequently and felt pretty comfortable in the woods, so setting out at 5:00 p.m. for a 4.1-mile hike around a lake in Harriman State Park seemed perfectly reasonable (no need to rub it in).

The deserted trail we were on was tough, and we loved every minute. About two hours in, though, something began to feel off. Time wise, we should have been nearing the end of the trail, so where on earth was that lake we were supposed to be encircling?

A short while later, the coveted lake came into view, but we couldn’t pretend not to notice how low the sun was.

“Maybe we should turn back?” my 19-year-old sister Hudy suggested.

“I don’t think that makes sense, we should be much closer to the end than to the beginning,” I calculated. At 22, I felt qualified to be the team leader. “Let’s keep going.”

But then the lake disappeared — it wasn’t supposed to — and the trail went on and on, deep into the woods. About an hour later, there was no denying it: We were on the wrong trail. We plowed ahead, desperate to outpace the setting sun, praying this trail would lead out of the woods soon.

Another long while of increasingly anxious hiking, and then it was almost pitch dark. Unfamiliar, eerie sounds began to ring out — the night animals were waking up.

And then I lost it, finding myself in the throes of a full-fledged panic attack. “We’re not gonna make it out. Oh my gosh, Hudy, we’re stuck here all night!” I cried, then screamed, then began to hyperventilate. My body shook violently and became so weak I could barely walk. To top it off, the cool night air against our skin, wet with sweat, left us freezing. And supplies? We entered the woods with one water bottle and one protein bar each, all gone within the first hour.

My thoughts became irrational: A lion will eat us for supper. A man with a knife will pop out from behind a tree and butcher us. One way or another, we’d be dead before the night was over.

Hudy swallowed her own panic to keep it together for both of us. She called our father, who told us to sit tight while he called Chaverim of Rockland. We had been hiking for many hours, which I assumed meant they wouldn’t get here for at least that long — if they managed to find us at all in the pitch dark. It didn’t seem possible.

We saw a shelter in the distance, and we trudged there. Our father called us back a short while later. “Chaverim is on their way, don’t move. They’re trained, they have supplies, and they’ll be there soon. They want you to describe any landmarks you passed.” Thank goodness for the two shelters we’d seen, because other than those it was just endless trees. He also told us that since we were over 18, the Park Rangers wouldn’t search for us until morning — they won’t risk their own safety by venturing into the woods at night.

Hudy and I sat in the shelter playing word games to distract ourselves, the panic somewhat muted but still very much there. About 45 minutes later, there was a beam of light, and we heard the magic words: “Is anybody here?” I ran toward the voice, screaming like a crazed person. “We’re here! We’re here!” The relief I felt was indescribably intense — I couldn’t believe we were safe. My body continued to shake even after I calmed down mentally.

We were in no condition to move yet. The rescue team made us eat and drink electrolyte water, and insulated us with thermal ponchos until we stopped shivering. When we were deemed ready, they led us out of the woods the same way they came in. I have no idea how they knew the route in the dark, but they were very sure of where they were going. Along the way we met up with a backup team; because of my panic attack, they brought in extra manpower to carry me out on a stretcher if needed. It was ten selfless men, my sister, and me.

Within an hour of being rescued, I got behind the wheel and drove home. I walked in at midnight.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 920)

Oops! We could not locate your form.