Our Woman at the Hostage Headquarters

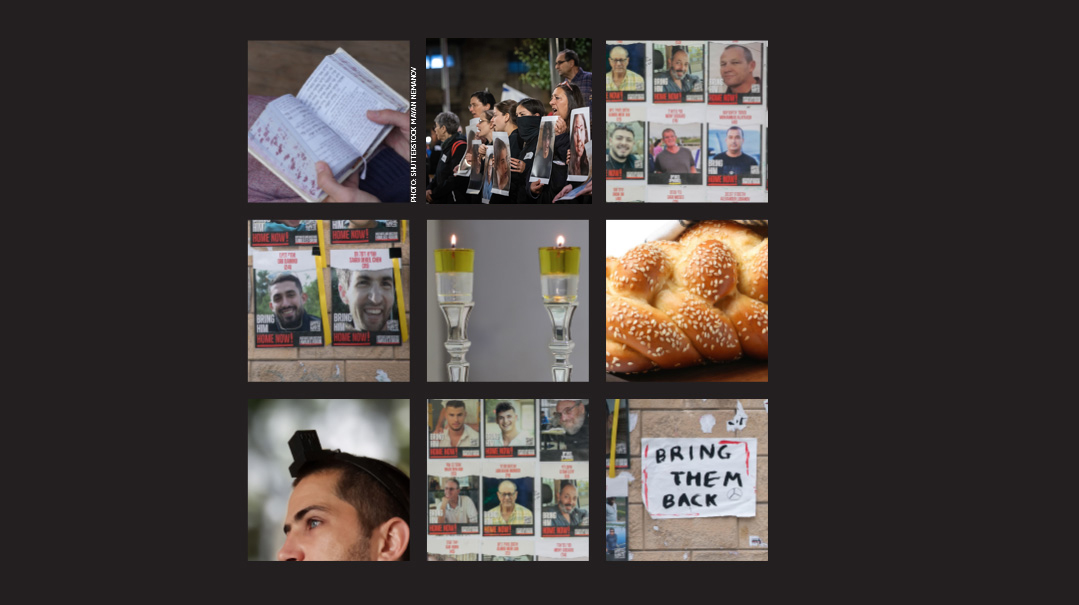

| July 23, 2024Armed with tefillin and neiros, Riki Siton is fighting to free the hostages

Photos: Flash90, Riki Siton

She may look out of place in her sheitel and long sleeves, but Mrs. Riki Siton is a familiar presence at the Mateh Mishpachot Hachatufim — the Tel Aviv-based Headquarters for the Families of the Hostages — and at Hostage Square, where she does her utmost to bring frum-flavored chizuk to the hostages’ families

When Riki Siton rode the elevator up to the Mateh Hachatufim in October, she questioned her sanity. “I asked myself, ‘What am I thinking coming here? I’m a chareidi woman from Bnei Brak! How can I look someone whose child is being held hostage in Gaza, in the eye?! What can I possibly say?’ ”

Instinct told her to do an about-face and return home, but Hashgachah intervened. At that moment, the elevator doors opened and Sheli Shemtov — whose 24-year-old son Omer was taken hostage on October 7 — looked straight at Riki, and with a broad smile said, “Achoti hachareidi, thank you for coming, we were hoping you would come. Please, bring your friends!” Immediately after she’d heard her son had been kidnapped, Sheli had called for achdus among Am Yisrael.

Where Are the Chareidim?

Riki is a program director at Ayelet Hashachar, a renowned Israeli bridge-building and Jewish education organization, and today also spearheads a movement of women backed by Ayelet Hashachar, who endeavor to bring a frum presence to the Mateh Hachatufim. I catch her at nine p.m., when she’s in her car, on the road up north to deliver tefillin to a man interested in keeping the mitzvah as a zechus for the hostages’ return. She’s accompanied by Julie Cooperstein, the mother of 20-year-old hostage Bar (Bar ben Julie), who was also kidnapped from the music festival, where he was part of the security team.

Riki tells me how her involvement with the Mateh Hachatufim began. “Often groups of secular people visit Bnei Brak to see how chareidim live,” Riki tells me over the phone. “I’ve never advertised. Somehow they find me. Some of them come through government programs, others by word of mouth. So someone from Hod Hasharon reached out to me at the beginning of the war, someone who’d once been in my house on one of these trips. This woman asked me, ‘Where are the chareidim? Why aren’t they visiting the families of the hostages? Do they care? You know a lot of people, bring them so the hostages’ families will see that their plight matters to the chareidi world as well.’

“I told her that I had to first see the situation before I brought other people with me, and that’s how I found myself in the elevator on my way up to the Mateh in Tel Aviv.”

“When the war broke out,” Riki continues, “I was in a state of total shock, numb with disbelief and pain. I went to many of the funerals of the residents who were killed, and traveled down to Eilat to visit displaced families from the kibbutzim that had been targeted.”

Through her work at Ayelet Hashachar, Riki had been close to many families from the ill-fated Gazan-border communities of Kerem Shalom, Re’im, and Be’eri. “Ayelet Hashachar has an initiative that sends avreichim to live on secular kibbutzim,” she explains. “By simply living together with ‘the other,’ the kibbutznikim started to taste and see the concept of ki tov Hashem. Through personal connection with their chareidi neighbors, the walls between the sectors dissolve and stigmas fall away. Because when you meet a person up close and have an opportunity to speak to them, you start to understand more and are open to learning from them.”

Riki is also involved in Ayelet Hashachar’s Chavrusa Project, which pairs secular men and women with a frum one. The word chavrusa is used loosely here, not strictly in its classic context of study partner. There’s another objective: friendship and connection.

“You can’t make a person become frum,” Riki explains. “You can’t change a person. You can get to know them, see them for who they are, show them your lifestyle. That has a tremendous effect.

“Don’t get me wrong, if you have the zechus to be a part of someone’s journey to Yiddishkeit, that’s fantastic. But that’s not the main goal. Eleven years ago, I had a chavrusa who saw our relationship as something of an anthropological foray into the world of chareidim. She had no intention of ever becoming frum and was entirely uninterested in learning anything related to Judaism. I sent a question to Rav Aharon Leib Steinman: Should I still be her chavrusa? Rav Steinman’s surprising answer was that if she wants a chavrusa with a frum person, I must provide her with one. However, her chavrusa must be someone adequately grounded in her own Yiddishkeit.”

Riki pauses. “‘Because,’ said Rav Steinman, ‘if one Jew will hate another Jew a little bit less, that is chazarah b’teshuvah.’ ”

Accruing Zechuyos

Riki’s initial visit to the Mateh Chatufim opened an entirely new front in her expansive chesed enterprise. “When I met Sheli Shemtov at the hostage headquarters, I asked her what she needed,” Riki says. “And she answered, ‘A tefillah and a hug, in that order.’ ”

Sheli’s frank request inspired Riki to initiate the Tefillat Ha’imahot, a gathering of 400 women and families of hostages at the Tel Aviv art museum, a bastion of secularity. “Four mothers of hostages led the crowd in tefillah and literally rent the Heavens. Hundreds of other women from across Israel and the world joined via live hookup. The women then broke into groups and engaged in other activities, like hafrashas challah, seudos amen, and singing. It was a super emotional evening.

“We thought of what we could do next, how to keep the momentum going,” says Riki. “We wanted to open an Ohel Tefillah at hostage square in Tel Aviv, a dedicated place for people to daven on behalf of the hostages, but things weren’t moving forward.”

That’s when Riki met Julie Cooperstein. Julie’s no stranger to challenge. Her husband was permanently disabled in a car accident and Julie has four young children to care for, in addition to Bar. Julie is a baalas teshuvah — she became frum on her own, once she was already married with children — and with her scarf-wrapped head, she stands out among the constellation of hostage parents. But she also wanted to claim her space at Hostage Square, space where she could daven and bring frum people to show support to the hostages’ families, and most significantly, provide the hostages with spiritual merits. It’s to her determination that the Ohel Tefillah was born.

“Understand,” Riki emphasizes, “that an Ohel Tefillah at hostage square in the heart of Tel Aviv is an oxymoron. It’s entirely unprecedented.”

Julie’s partnership with Riki was also the catalyst for other spiritual ventures with secular women, like Rosh Chodesh trips to kivrei tzaddikim, visits to gedolei Yisrael, major tefillah rallies, Shavuos in the Old City of Jerusalem for hostage families, and other Yom Tov events.

The Shabbos Project was yet another Julie-Riki collaborative brainchild. It developed from a question Riki asked Julie when they first met, the same question Riki had asked Sheli Shemtov: “What can I do for you?”

“Julie, despite her significant challenges at home, is a tzaddikah. She didn’t want to ask for anything, certainly nothing material,” Riki avers, “but she requested we do something related to strengthening Shabbos observance as a zechus to bring Bar home. So I recorded a video of her pleading, as a mother, for people to do something toward Shabbos observance. More than three thousand people signed up on the Google form that accompanied the recording, people who otherwise weren’t keeping Shabbos, declaring they were committed to doing something for shemiras Shabbos.”

Julie’s call from the heart materialized as Shabbat B’tik — Shabbos in a bag. These Shabbos kits were outfitted with everything a person endeavoring to keep Shabbos would need — candlesticks, a kiddush cup, challah cover, bentshers, hot water urn, hot plate — to name a few. At this point generous donors from Long Island who Julie met at the Ohel Tefillah hopped onto the initiative, sponsoring and assembling some of these kits. They were distributed to families of hostages as well.

Bar’s 22nd birthday on Pesach was the incentive for another Shabbos campaign. Employing a clever slogan, “Hashabbat L’hashavat Hachatufim — Shabbos for the Return of the Hostages,” Riki and Julie designated Shabbos Hagadol as the target Shabbos in a worldwide initiative toward more Shabbos observance.

“We interviewed women who had returned from Hamas captivity and mothers awaiting the return of their children. They spoke about Shabbos and asked people to light candles and contribute to Shabbos observance in some way, as a zechus for the hostages’ safe return,” Riki says.

The Tefillin Project

Riki’s current initiative, the Tefillin Project — the reason she’s driving hours up to northern Israel as she speaks with me — is also to Julie’s credit. Like most of Riki’s other initiatives, it evolved from the prosaic. Julie was distressed that Bar’s tefillin were languishing, unused, while he was in captivity. Riki sent out a message out asking if there was anyone who didn’t ordinarily don tefillin and was interested in committing to wear Bar’s pair until his safe return. “In my naivete, I left my phone number as a contact, assuming only four or five people would be interested,” Riki says.

To her utter shock, dozens of men responded, each one justifying why he specifically should be the one to wear Bar’s tefillin. Strikingly, none of the respondents wore tefillin themselves on a regular basis, yet here they were, fighting for the coveted role of donning Bar’s pair in his absence.

Riki and Julie identified a thirst for this daily mitzvah in this outstanding response and immediately capitalized on it. “We ordered thirty tefillin sets for male hostages and matched up men who were not otherwise wearing tefillin, giving them the responsibility of donning ‘their’ hostage’s tefillin, until he returns from captivity.”

To ensure this matchup was endowed with the requisite commitment and spiritual significance, Riki and Julie purchased tefillin bags and embroidered each one with an individual hostage’s name, a gesture that would keep the hostage in the forefront of the tefillin wearer’s mind and an indication that each pair of tefillin was awaiting a hostage’s safe return. They also had the volunteers sign a contract, pledging to wear the tefillin every day and obligating them to return the tefillin if they no longer wore them.

They’ve distributed countless sets to their surrogate wearers, whose tefillin merits will be accredited to “his” hostage, and there are more sets patiently waiting for volunteers to wear them.

“Right now, we’re on the way to deliver a pair of tefillin to a fifty-seven-year-old man who hasn’t worn tefillin since his bar mitzvah.

Another pair went to a kibbutznik who asked to wear them for a friend who’d been kidnapped to Gaza. The friend had never worn tefillin; he hadn’t even celebrated a bar mitzvah in his youth. “When he’s released, I’ll show him what it is, that I had to wear tefillin for him,” the friend said with a chuckle, “and then I’ll teach him how to do it himself!”

The tefillin project has prompted many deeply moving accounts from first-time wearers. The youngest person committing to tefillin is 17; the oldest is 83. They’re paired with the youngest and oldest captives, respectively. A pair of identical twins committed to donning tefillin for Gali and Ziv Berman, a set of identical twins in captivity. Two bosses accepted the mitzvah on behalf of their employees, one of whom is Sasha Trupenov (see “Here For a Reason” Family First Issue 890).

Perhaps most poignant is the story of Almog, who was rescued in a daring operation several weeks ago, along with Noa Argamani, Shlomi Ziv, and Andre Koslov. “The tefillin project was launched a week before their rescue,” Riki says, “and two days after their release, we were on the way to deliver tefillin to Sasha Trupenov’s boss when we met Almog. Obviously, we were thrilled to see him, and our meeting was very emotional. Then we realized we had his tefillin in the car! We were planning on dropping them off with ‘his’ volunteer, but we gave the tefillin to him directly instead, two days after his rescue.

“But the story doesn’t end there,” Riki continues, “because that morning Almog had decided to go to shul to daven, and asked his uncle for a kippah. He’d looked at the kippah his uncle gave him and had said, ‘Wow, you gave me the kippah I used at my bar mitzvah!’ At shul, Almog had received an aliyah, and to his surprise, the baal korei read the pesukim from his bar mitzvah parshah, parshas Naso. When Riki and Julie handed him his tefillin, he told them, ‘You brought my bar mitzvah full circle.’ ”

The Female Hostages

With the tefillin project in place, Riki determined that the female hostages needed a project of their own as well.

“There are girls and women held hostage in Gaza. It’s unthinkable! What could we do for them? We thought for a long time and found a mitzvah for them, similar to tefillin for men, and commissioned forty siddurim for forty female hostages, each one embossed on the front with the name of a hostage and inside a picture of her and her name for tefillah,” Riki says. “We give these siddurim to women who wouldn’t otherwise daven and ask that they say birchos hashachar and Shema. This week we’ll travel to army lookout points and distribute the siddurim of hostages who operated at military lookouts to their military lookout counterparts. We want each woman’s hostage to be close to her heart, so we match them up according to commonalities like these.

“In addition, we had an evening in the Old City dedicated to the female hostages called Lo B’li Biti — Not Without My Daughter, where we invited the mothers of captive women, we sang shirei Geulah, and heard words of chizuk.”

At this point, Rikki informs me that she’s arrived at the home of her tefillin dropoff, and the conversation winds down. It’s past ten p.m., and I picture the hours-long ride she has ahead of her, back to Bnei Brak. How does she have the energy to keep innovating, investing physical, emotional, and creative energy into these outsized projects?

Unwittingly, Riki answers the question for me. “We all have a responsibility to do something small to garner more zechuyos for the hostages, to be more aware, because when every small bit comes together, it grows into something immeasurable. When I started all of this, I never imagined or intended for it to look like this. I simply came to be there and try to do what I could. And when Hashem sent things my way, I answered the call.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 903)

Oops! We could not locate your form.