Our Mensch in the Senate

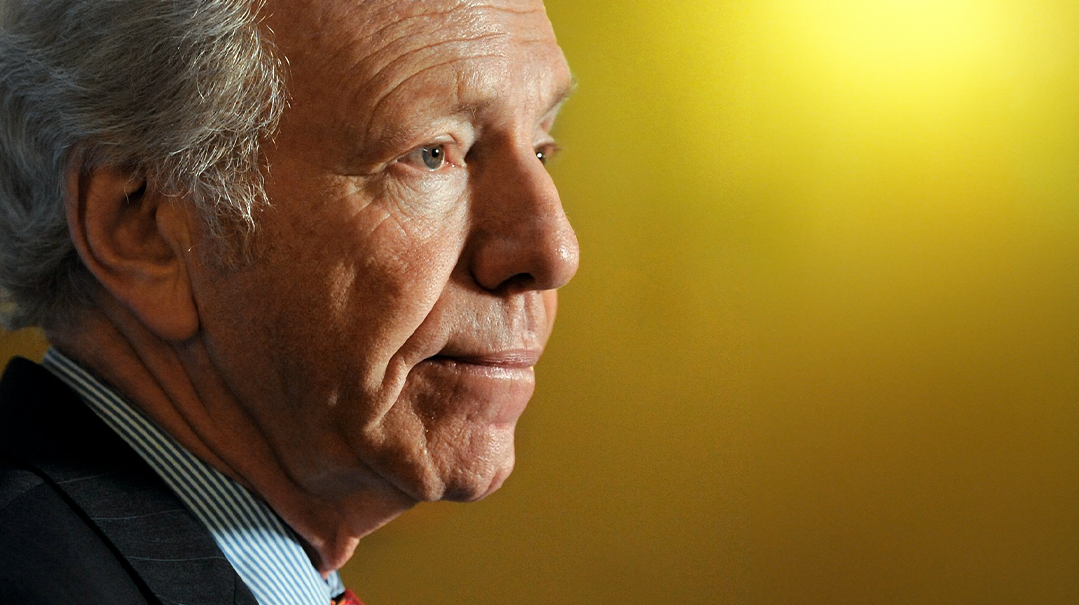

Senator Joe Lieberman was from a disappearing breed of politicians and statesmen

Photos: AP Images, Flash90

Conscience of the Senate

Rabbi Menachem Genack

S

enator Joseph Lieberman, who died unexpectedly last Wednesday following complications from a fall, was a man of extraordinary character, grace, humility, and devotion to his family, nation, and G-d. We were close friends, and we studied Torah together for decades. We studied together the previous Friday and set up a time to do so again last Friday. Instead, tragically, last Friday I attended his funeral.

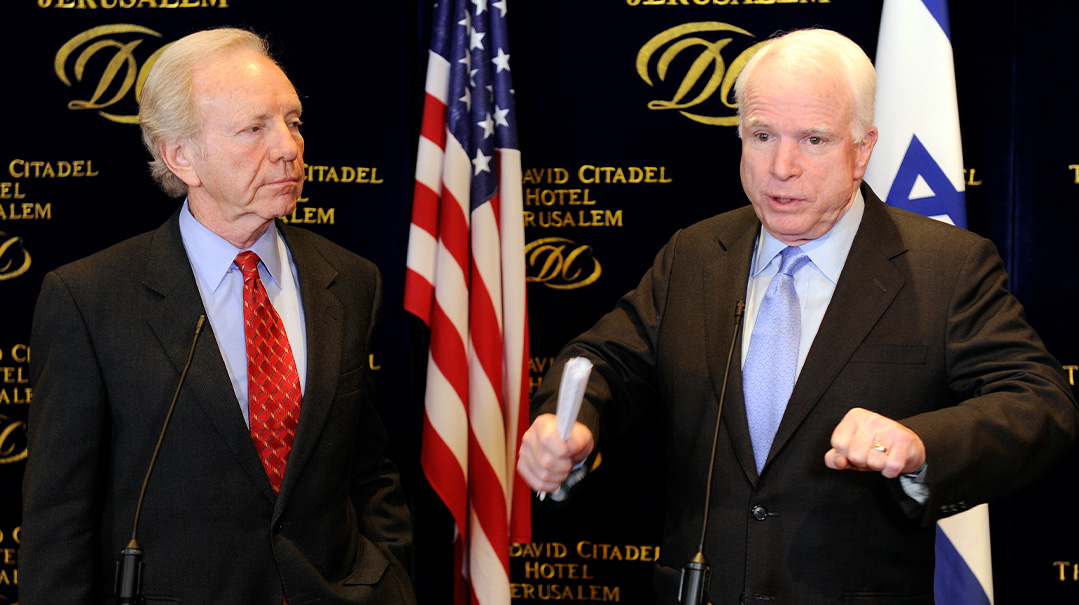

Senator Lieberman’s life and work were distinguished by his integrity, his adherence to principle, and his moderation. Sadly, he was from a disappearing breed of politicians and statesmen. He was known for his commitment to bipartisanship and his friendships with both Republicans and Democrats; together, he and his Republican friends Senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham were known as “the Three Amigos.”

Senator Graham once told me that when he grew up, he wanted to be like Senator Lieberman. Senator McCain and Senator Lieberman would often travel together on Senate business. On one such trip, McCain told me, he woke up to find Senator Lieberman wrapped in tefillin, praying. McCain said he thought he had died and gone to heaven. On another occasion, Senator McCain, in his colorful military language, expressed his frustration at having to ride with Senator Lieberman on a Sabbath elevator that stopped at every floor.

Shabbos was in fact central to Senator Lieberman’s identity. If he had to vote on Shabbos, he would walk to the Senate. When he was selected as Al Gore’s running mate in 2000, Senator Lieberman was the first Orthodox Jew to achieve such prominence. But instead of being impediments, his steadfast faith and religious commitment made him a more appealing candidate, and also gave Jews and other minorities the pride to stand up for their beliefs. His book about Shabbos, The Gift of Rest, published by OU Press, is an eloquent testament to the power and meaning of this day. When it was published, I sent copies to all OU-certified companies to give them an understanding of what we are all about.

A staunch defender and ally of Israel, Senator Lieberman was especially proud of his daughter Hani, who made aliyah with her family, and he would visit them in Israel often. At Hani’s wedding, I was dancing with Senator Lieberman and his Connecticut colleague Senator Chris Dodd next to a large mechitzah decorated with images of Israel. Senator Lieberman, with his ever-present sense of humor, commented to Dodd that he took the dance to be an endorsement of settlement expansion. Last Friday, after our Torah study session, Senator Lieberman told me he had just published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal in which he criticized his friend Chuck Schumer’s speech about Bibi Netanyahu.

With regard to foreign policy, Senator Lieberman was an old-school Scoop Jackson Democrat, in favor of a muscular United States protecting world order. His support for the Iraq War cost him dearly in his party — although, even after he was defeated in the Democratic primary in Connecticut, he still won his Senate race as an independent.

Senator Lieberman was known as the conscience of the Senate. He was always proud of his advocacy for civil rights in his student days; he once introduced Martin Luther King Jr., who had come to speak in his school. In my book Letters to President Clinton, I included a letter from Senator Lieberman that asks a fundamental question. Why in Judaism does day follow night? Wouldn’t it make more sense for the day to begin with sunrise, when man wakes up and begins his work, rather than at night, when we sleep?

His answer contained a fundamental idea:

One answer may be that the Bible thought that we could not properly appreciate the daylight if we did not first experience the night. Night represents adversity, challenge, non-cognition. Even the mighty King Solomon is seized by terror at night: “Behold it is the litter of Solomon. Threescore mighty men are about it… because of the dread in the night” (Song 3:7–8).

Day, blessed by the warmth and light of the sun, is a period of security, productivity, growth, and hope. It is touched by all G-d’s blessings. However, to appreciate and properly evaluate the gifts of the day requires the experience of the emptiness of the night, because the night teaches us the importance of faith and courage.

Psalm 92 is a song for the Sabbath day. In it, the Psalmist chants, “It is good to give thanks to the L-rd… To declare Your lovingkindness in the morning, and Your faithfulness in the nights” (Ps. 92:2–3). The morning, replete with G-d’s bounty and benevolence, requires that we are grateful for His infinite kindness; but the night, enveloped in dark trepidation, requires faith.

There is a rabbinic tradition… that this Psalm was not written by David, but by Adam. Adam came into being, sinned, and was expelled from Eden at the close of the sixth day. When the night of the first Sabbath descended, Adam thought that his sin had brought the end to Creation. The light was gone and he was surrounded by gloom. When the sun rose that Sabbath morning, and with it the message of hope and redemption, Adam sang this song of praise to G-d. After the night comes the day, with its promise of salvation and the hope for a new and better tomorrow.

President Clinton responded to this note:

Dear Joe:

Thank you for your reflections on night and day, sin and repentance. All of us need to reflect on these things, no one more than me.

After I published an article about Rav Soloveitchik and his warm relationship with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Senator Lieberman wrote to me to express his appreciation: “The stories are compelling in their content but also because of what they say about the respectful and embracing relationship between these two great Rabbis, who were the leaders during the 20th century of two different branches of Judaism generally thought to be divided… You have [imparted] the message of how possible and important Jewish unity is if we respect each other and work to achieve it.”

This message was one that Joe Lieberman embodied — that despite our differences, what united us was greater than what divided us. This was a message he stood for both as a Jew and as an American. Senator Lieberman was a one-of-a-kind mensch who uniquely represented the Jewish People at the highest levels of government with such dignity and charm. He will be sorely missed.

Here He Was, with Us

Yosef Zoimen

ATKabbalos Shabbos, the Carlebach shul in Tzfas is adorned with the tapestry of Klal Yisrael. An eclectic group of men, seemingly with little in common — from white, bedazzled, free-flowing Carlebach followers to chassidim straight out of Boro Park, and so many in between.

Then came us — four bochurim from the Mir, talmidim of Rav Elya Baruch Finkel ztz”l and Rabbi Elimelech Resnick — having rolled into our kloiz (closet — it was not big enough to be called a tzimmer), just an hour before, during this off Shabbos in June 2004. We were all there to connect to HaKadosh Baruch Hu in one of the coziest places on earth, this shack of a shul in the mystical city of Tzfas.

Out of the corner of my eye during Minchah, I saw a Yid with a beautiful smile and a twinkle in his dark eyes. From far away I could tell he was an older American, likely Modern Orthodox — no surprise in a place like this — also wanting to connect to the One Above.

Looking closer, I was taken aback: It was the same man I had seen onstage just four years earlier with Al Gore, stumping across America as the first-ever Jewish candidate on a major-party presidential ticket, with plans to be our shomer Shabbos vice president. Still a prestigious United States senator, Joe was here with some of Klal Yisrael’s finest neshamos in the hills of Tzfas. He probably could have been headlining a VIP Shabbos in Yerushalayim’s King David Hotel; instead, here he was, in a shul infused with a musty smell like the famous mikveh nearby, but one of the holiest places to connect.

No one gave Joe a second glance the entire Shabbos. He danced round and round in circles during Kabbalas Shabbos, on one side clasping the hand of a Teimani Yid with trailing techeiles tzitzis and on the other gripping the hand of the shaved-head ex-Mossad bodyguard — just a regular Yid in the crowd, singing along to Reb Shlomo’s niggunim.

After Maariv on Motzaei Shabbos, Joe Lieberman, probably one of the most highly placed Jews on the planet, gave a Havdalah tutorial to three Israel bodyguards who, by the looks of them, probably never experienced Havdalah before. He showed them the candle we hold, described to them the sadness we feel when Shabbos departs, and explained how smelling the spices symbolizes consolation for losing that special Shabbosdig neshamah.

Throughout Havdalah, Joe showed these towering hulks what to do, motioning them to look at their hands in the light of the fire, sparking the pintele Yid deep inside each of them. While we may have been in Tzfas that weekend to take a break, we witnessed a proud Yid who never took breaks.

When the Senator Came to Shul

Gedalia Guttentag

IT was Friday night a few years ago when Michael, a friend from Atlanta, Georgia, then living in Tel Aviv, came to visit us in Ramat Beit Shemesh for Shabbos. I knew that Michael, who grew up traditional, would appreciate the low-key, out-of-town America feel of Ahavas Sholom, my local shul, and so we headed there to daven.

Sometime during Kabbalas Shabbos, I looked to my right and did the proverbial double-take. There, on one of the shul’s modest pews, sat an honest-to-goodness United States senator. And not just any old senator. It was the one who’d almost become vice president.

Naturally, I nudged Michael, who immediately recognized Joe Lieberman. I went back to my siddur with all the nonchalance of someone who’s used to VIPs roaming his local shul.

After davening, we went over and I introduced my guest as a fellow countryman. In his patrician yet genuinely warm way, the senator exchanged a few words with Michael, and then it was my turn.

I’d been moved by Joe Lieberman’s The Gift of Rest — an ode to Shabbos and to maintaining one’s values at the top of America’s political ladder — and so I said so.

The senator paused for a second, and then replied with some words that said a lot about this proudly Orthodox Jew who’d risen so high, and his sense of priorities.

“Out of everything I’ve ever done,” he said thoughtfully, “that book means the most to me.”

Bringing Pride to the Jewish People

A. D. Motzen

Ifeel wholly inadequate to be sharing personal reflections about Senator Joe Lieberman. Videos and pictures of us together have been circulating recently, but, unlike my family members from Stamford or Riverdale, I didn’t attend the same shul as Senator Lieberman; and, unlike my senior colleagues at Agudah, my interactions with him over the last 20 years were limited. However, that didn’t stop the senator from making his neighbor, my grandmother, think that we were old buddies.

When, in recent years, Senator Lieberman would see my grandmother on Shabbos, he would frequently tell her I was making a kiddush Hashem, emphasize how important my work at Agudah was for the Jewish People, and fill her heart with pride. Cynics may see in his words a politician’s providing a constituent with what she wanted to hear. But my even own limited interactions with Senator Lieberman, like the experiences of so many others, proved that the feelings he expressed were genuine and fit perfectly with who he was and what he stood for.

One of the issues that he was most passionate about as a senator was school choice. He helped enact the DC Opportunity Scholarship and later saved the program from elimination (twice) during the Obama administration. At a 2015 event hosted by the American Federation for Children, on whose board he served, Senator Lieberman described school choice as the most important domestic issue in the country.

At that conference, and at many subsequent school choice events, he thanked me and my Agudah colleagues profusely. He was genuinely proud that the Orthodox community was now helping to lead the school choice movement. He used the same words that he would later tell my grandmother, “What you are doing is so important.” Perhaps he saw in us the continuation of the work he had started.

Senator Lieberman frequently encouraged Orthodox individuals and groups like Agudah to be active in the public policy arena and to strive to make a kiddush Hashem by being true to Torah values in our words and actions. It’s what he did. As my colleague Rabbi Abba Cohen said, “He didn’t try to impress or hold himself out as a role model, but he influenced others by his actions, modestly, naturally, and without fanfare.”

Senator Lieberman was especially close to Agudah’s late president Rabbi Moshe Sherer. In a letter sent to Senator Lieberman in July 1995, Rabbi Sherer wrote, “I owe you a very great debt of gratitude for your redeeming my faith in the political scene, that there can indeed be individuals who enter what is often a subterranean cesspool, and demonstrate how they can emerge not only untainted but also shining with eternal values.”

Earlier this year, I asked Senator Lieberman to participate in a film Agudah was producing in advance of Rabbi Sherer’s 25th yahrtzeit. Asked on camera how to define leadership, Senator Lieberman said, “The ultimate test of leadership is: Did you achieve anything for the group that you are a leader of?” Senator Lieberman was a leader of many “groups,” but as the undisputed leader and mentor of the now growing number of Orthodox elected officials and Jews in politics, he achieved a lot.

Thanks to the media coverage of the 2000 campaign, and later through his book on the topic, Senator Lieberman helped educate millions of Americans about Orthodox Jewish practices and Shabbos in particular.

My colleague Rabbi Cohen told me that when he was meeting with Jewish students, they were more interested in knowing about “Senator Lieberman, the Sabbath-observant Jew” than whether or not he had ever met the president or vice president. Similarly, when Mr. Lieberman ran for vice president, random people stopped Rabbi Cohen on the street to ask him about Orthodox Judaism. It was clear the senator and his Torah observance had made an impression on them and intrigued them.

When Mr. Lieberman was criticized by some liberal Jewish groups in 2000 for the “overt expressions” of religious belief in his campaign speeches, Agudah defended him. Yet ten days later, Agudah felt compelled to publicly but respectfully take issue with something Senator Lieberman said about Orthodox Judaism.

As my colleague Rabbi Avi Shafran explained at the time, Lieberman “was running for vice president and not chief rabbi,” and never claimed that every decision he made or the policies he supported were representative of Orthodox Judaism. The senator would later use a similar line to explain that while he was a proud Orthodox Jew, he was simply a lay person and not a rabbi.

Senator Lieberman once spoke at an Agudah dinner a week or two before Shavuos. He started his remarks by saying how all peoples — Jews and non-Jews alike — have embraced Pesach, the festival of freedom from oppression, but that somehow nobody knows about Shavuos. That is a terrible mistake, he said, because freedom without Torah — without morality, without restraint, without Hashem — is dangerous and destructive. Too many people, he said, are familiar with only the first words of Hashem’s admonition to Pharaoh — “Shalach es ami [Let my people go]” — and totally ignorant of the second part of the admonition — “V’yaavduni [so that they may serve Me].”

After the dinner, Rabbi Zwiebel had occasion to speak to the Philadelphia Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Elya Svei ztz”l, who said, “Der Senator hut gut gezogt — the Senator spoke well.”

The senator’s frustration over Shavuos being so ignored by so many was why he later wrote the book With Liberty and Justice: The Fifty-Day Journey from Egypt to Sinai. This week I took my copy off my bookshelf and re-read the inscribed cover. It says, “For A.D. Thanks for your work.” Once again, his message of appreciation was consistent!

Interestingly, I purchased the book soon after it came out in 2018, and I was reading it on my way to the annual conference of the American Federation for Children. The gentleman sitting next to me “bageled” me and revealed me that he too was Jewish and that his grandfather was an Orthodox rabbi in the Dakotas and later in Boro Park. He talked about how my wearing a yarmulke puts a greater responsibility on me to act properly, since those around me will be looking at everything I do. He then mentioned that he was a big fan of Senator Lieberman and inspired by his principled reputation. A few hours later, my seatmate was my guest at the Agudah table, eating a kosher dinner… and meeting Senator Lieberman in person.

In 1999, Senator Lieberman was one of several lawmakers to eulogize Rabbi Sherer on the Senate floor. At the end of his comments, he said that in Judaism, we believe that the best way to honor someone’s memory is to live by the principles that guided his own life.

While the greatest tribute to Joe Lieberman is that there are Jews whom he inspired to strengthen their Shabbos and other observance, he will also be honored by the emergence of new generations of Orthodox Jews engaged in public service, taking pride in their Jewish faith and, in their work, bringing pride to the Jewish People.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1006)

Oops! We could not locate your form.