Our Eternal Armor

| October 31, 2023The Ramban explains that Yishmael exists in order to drive Klal Yisrael to be mispallel and thus further their relationship with Hashem

Prepared for print by Shmuel Botnick

W

herever you live, whatever you do, if you are a believing Jew, you know that these times demand extraordinary measures. Our nation is under attack and even from afar, we each have a role to play. Rav Uri Deutsch, mara d’asra of Lakewood’s Forest Park community, sheds light on the cosmic nature of this battle, the spiritual ammunition we must utilize, and the proper attitude to fuel our avodas Hashem.

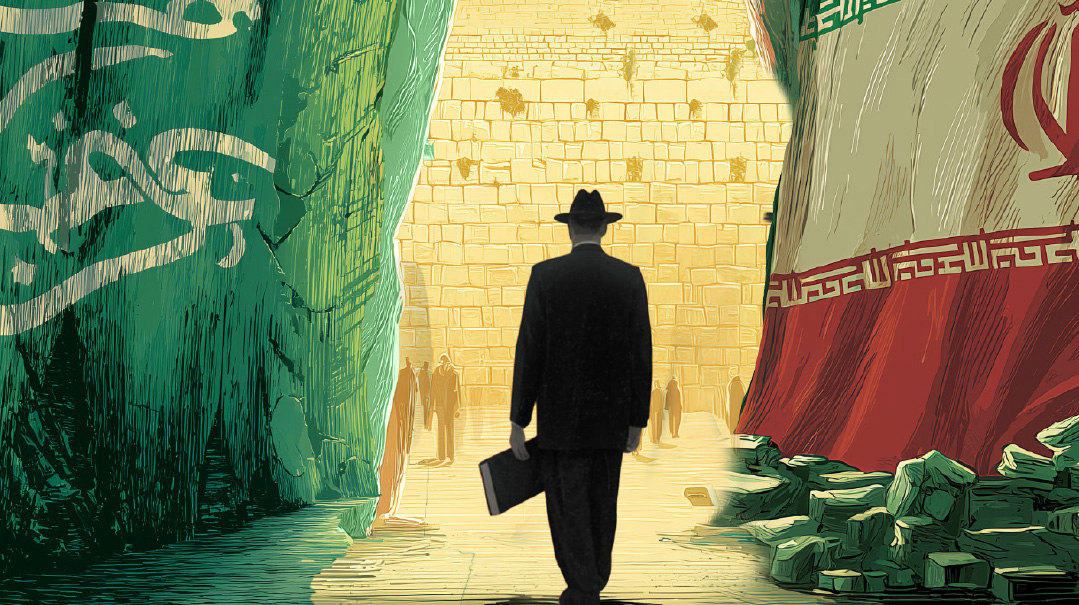

The Jews of Eretz Yisrael are currently engaged in a terrible conflict against Hamas. But seen from a more spiritual perspective, this isn’t limited to a single location or terrorist group; it’s a battle between Klal Yisrael and Yishmael, in which each and every Yid is a warrior. The first thing an army must do is identify the enemy. Who is Yishmael? What does it represent and what is its role in the world’s destiny?

Many in our community still remember when Rav Yitzchak Hutner was taken hostage by Palestinian hijackers in Elul 5731 (1970). After he was released, he delivered a ma’amar in which he discussed the difference between Galus Edom and Galus Yishmael.

In describing the leaders of Edom, the Torah uses the term melachim, kings. The Torah names the chieftains of Yishmael as well, yet does not reference them as melachim. Rav Hutner explains that the term “king” is tied to territorial dominion. The chieftains of Edom were granted an element of command over the region that was allotted to them. Yishmael, on the other hand, has no possessory hold over any territory. To this day, it remains a stateless nation.

Rav Hutner goes on to say that this is the deeper significance of Yishmael’s expulsion from Avraham’s home, as the Torah describes in parshas Vayeira. The eternal repercussions of this act have Yishmael playing no role in our spiritual destiny of Avraham’s household and deprived of any claim to his legacy. Therefore, his rage is that of the utterly dispossessed.

He may have no inheritance, but that’s not to say Yishmael has no purpose. The Ramban explains that Yishmael exists in order to drive Klal Yisrael to be mispallel and thus further their relationship with Hashem. This is particularly true in the area of tefillah, as we glean from Yishmael’s name, whose root word is shema — connoting that the pain he causes us prompts us to cry out and be heard. We see that Yishmael is a nation whose essential role is to compel Klal Yisrael to grow ever closer to Hashem Yisbarach.

The Rambam begins Hilchos Taanis by discussing, in dramatic terms, the proper response to an eis tzarah. He focuses on fasting, davening, and the blowing of chatzotzros. Today, in our current eis tzarah, we have seen a great intensification of tefillah, but we generally aren’t receiving the instruction to fast. We’ve also heard calls to increase limud haTorah and to strengthen shemiras Shabbos. The Rambam doesn’t mention either of these. Why is this so, and what, in fact, should be our primary focus?

As a general rule, the Shulchan Aruch writes that it is not our custom nowadays to place an emphasis on fasting. He also writes that when we do contemplate decreeing a fast, we must take into consideration the effect it will have on talmidei chachamim and its impact on their limud haTorah.

When it comes to tefillah, that should absolutely be the primary emphasis. The reason that the Rambam does not mention limud haTorah is because he is outlining the chiyuv d’Oraisa mandated during an eis tzarah. Limud haTorah is relevant as a zechus serving as a protection — but there is no specific mitzvah d’Oraisa relating to increasing limud haTorah during a tragic time. It is an objective we should always pursue. But when it comes to tefillah, the Rambam states that there’s a positive commandment to increase our davening in face of difficulty. The Ramban concurs with this view.

Regarding the role of limud haTorah, this comes from Chazal’s interpretation of the pasuk in parshas Toldos: “hakol kol Yaakov, v’hayadayim yedei Eisav — the voice is the voice of Yaakov and the hands are the hands of Eisav.” Chazal understand the “voice of Yaakov” as an allusion to both tefillah and limud haTorah, which counter the combative “hand of Eisav.” Klal Yisrael’s power is in its peh, its mouth. Limud haTorah is an exercise of the mouth — particularly Torah shebe’al peh, as its name suggests. Through the Torah learned with our peh, we can overcome Eisav.

The role of shemiras Shabbos can be explained based on the words of the siddur Siach Yitzchak by Rav Yitzchak Maltzan in his comment on the words of Pesukei D’zimra, “zera Yisrael avdo, bnei Yaakov bechirav.” There, Rav Yitzchak Maltzan speaks extensively about the meaning of being a part of Klal Yisrael. He explains that there are two critical distinctions between Klal Yisrael and the umos ha’olam.

The first is an absolute belief in the Hashgachah pratis of the Ribbono shel Olam. The second is the responsibility of bearing the load that Hashem places on Klal Yisrael’s shoulders. He continues to write that the primary medium through which our emunah in Hashgachah pratis is expressed is shemiras Shabbos, when we affirm our belief in the most basic principles of brias ha’olam and Yetzias Mitzrayim. The special protection afforded by shemiras Shabbos stems from the emunah that it generates, which is the distinguishing factor of being a member of Klal Yisrael.

So it seems that tefillah should be the primary focus during these very trying times. How should one balance increased tefillah vis-à-vis his responsibility to maximize all available time for limud haTorah? Should a yeshivah schedule increased Tehillim at the expense of scheduled sedorim?

These are weighty questions best left to our gedolim. Judging from past experiences, it is clear that, in a general sense, Torah is our primary protection. On the other hand, as we mentioned, there is an actual mitzvah to daven during an eis tzarah, and the responsibility of fulfilling a mitzvah takes precedence over learning. This is the factor that our gedolim are taking into consideration — we must certainly increase our davening, but how much tefillah should we engage in at the cost of limud haTorah?

Bakashos, requests for specific needs, are generally forbidden on Shabbos. However, in hilchos Shabbos, the Shulchan Aruch outlines the parameters for when bakashos are permitted, and distinguishes between ongoing tzaros versus acute present ones. When a tzarah presents immediate sakanas nefashos, then bakashos are permitted.

Along these lines, in the past, the hadrachah has been that, when there is a specific and intense crisis, and the potential loss of a Yid’s life is, chas v’shalom, imminent, then yes, we do take time off of sedorim to daven. When the tzarah is prolonged, however, then tefillos are added, but time is not taken from sedorim.

This is the general guideline — although it is very difficult to determine when a tzarah moves from being specific and imminent to being prolonged.

It’s easy to say that one should “increase his dedication to learning” — but not quite as easy to translate that to action. Some are doing their best to increase their learning time, but many are already learning three sedorim a day, or learning as much as they can outside of their work hours. If one is already learning as much as he can, how can he “increase his learning?”

If someone is going through a personal tzarah, we’d all expect him to daven with an increased sense of urgency, beyond his usual practice. Although we don’t usually view limud haTorah as an emotional engagement — that’s something more commonly associated with tefillah — there does exist a concept of “learning with urgency.”

This means strengthening our awareness that, aside from the intellectual aspect of Torah, it is also the greatest vehicle toward dveikus in Hashem. The first step in furthering our learning is strengthening our cognizance of the spiritually transformational impact inherent in limud haTorah.

In addition to that emotional urgency, there is another point. The same way we currently find ourselves murmuring words of Tehillim even when not formally designating time to do so, we should be seizing our free moments to learn Torah.

Everyone has certain subjects in Torah that they particularly enjoy. It may be a certain masechta, or it may be a perek in Nach. One can take the current events as an opportunity to learn the nevuos in Yeshayahu, Yirmiyahu, and Yechezkel that prophesy the era of geulah. Engaging in limudim to which one feels a personal draw brings one to have thoughts of Torah on his mind constantly, even while not participating in a formal seder limud.

We usually associate “urgency” with tension and stress. During this time, should our learning take on a tone of severity? Should the joy and uplift usually experienced when learning Torah be somewhat toned down? And, speaking more generally, being b’simchah is always a central value in Yiddishkeit — ivdu es Hashem b’simchah. How should current events affect our application of this principle?

It’s important to clarify the definition of simchah. The Chazon Ish presents what seems to be a difficult dichotomy. The Gemara tells us that “ein nevuah shoreh ela mi’toch simchah, one cannot merit prophecy unless he is in a state of joy.” The Chazon Ish questions this by pointing to the many nevuos whose message is the terrible calamities that Klal Yisrael will face in retribution for their aveiros. How is it possible for such nevuah to materialize? Surely the navi was not in a state of simchah upon hearing of such terrible tidings.

The Chazon Ish explains that a Yid can in fact fully participate in the pain of Klal Yisrael while still being in a state of simchah. To understand how this is so, we must establish a working definition of “simchah.”

We typically translate it as “joy,” which infers a sense of joviality, of lightness, even comedy. This is not correct. The Chazon Ish explains that the concept of simchah is the idea of an inner calm, an inner sense of satisfaction that comes from being connected to that which is meaningful, eternal, and self-fulfilling.

Rabbeinu Yonah, in the beginning of the fifth perek of Berachos, discusses at length the term found in Tehillim: “v’gilu bire’adah, and rejoice with trembling.” There is no contradiction between these two values. The gilah that the passuk refers to is the joy of the satisfaction of fulfilling one’s purpose. This does not conflict in any way with our obligatory sense of awe of Hashem.

It is true that we are living through difficult times, but there is no mitzvah to be b’atzvus, there is no mitzvah to be anxious, and there is no mitzvah to remain in a constant state of fear. Throughout the Torah, we never find a command to feel a certain emotion unless it helps advance our aliyah in avodas Hashem.

The phrase that should define our current state of mind is “v’gilu bire’adah.” We must be serious and focused and do whatever we can to increase our zechuyos. But at the same time, we should maintain a sense of joy at being able to fulfill life’s purpose, along with the awe we must have for Hashem Yisbarach.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 984)

Oops! We could not locate your form.