Onward to Identity

A former SS soldier finds his true calling as a member of the Chosen Nation

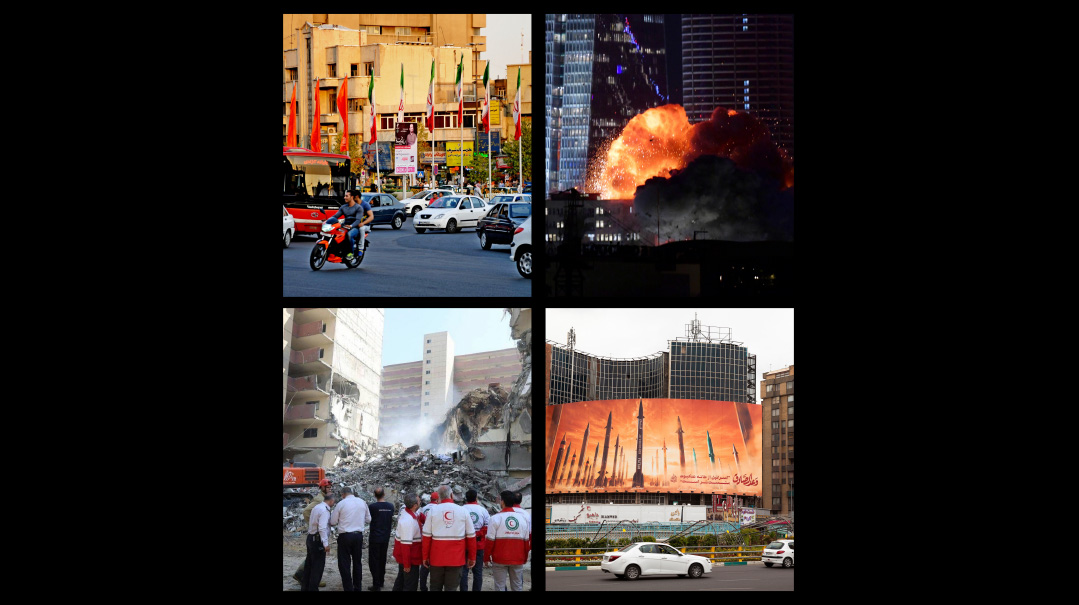

Photos Mendel Photography

T

o those who see him shopping in the kosher grocery in Edgware, London, a velvet yarmulke atop his snowy mane, Yitzchak von Schweitzer is another friendly older face in an increasingly chareidi and youthful neighborhood. Still active at 97 years old, he could be anyone’s great-grandfather.

Even if you happen to know his name, with its aristocratic Germanic overtones, or catch the shades of South African in his accent, there’s no hint of anything out of the ordinary.

But Yitzchak von Schweitzer is no run-of-the-mill retiree, come to spend his golden years puttering around this sedate London suburb.

He’s a man who’s been on a journey and a man with a past — one that contrasts strangely with his current humdrum surroundings.

Born Helmut von Schweitzer to a family of Austrian Catholic aristocracy, he served in the Hitler Youth, fought in the Waffen SS against the Russians, removed unexploded ordnance in London’s blitzed ruins, then became a successful businessman in South Africa where he and his wife (Pam, now Rivka) converted to become Orthodox Jews.

For many years, Yitzchak didn’t hide that astonishing biography, but neither did he advertise it. He well knew that his short service in the combat branch of the SS, together with his subsequent conversion, raised uncomfortable questions.

So he largely stayed quiet. Those who sat next to him in his local shul in South Africa and then Edgware knew him as the pleasant, unassuming gentleman who put on his tefillin, attended shiurim, conscientiously asked sh’eilos from his local rabbi, and donated toward the shul’s youth program.

From the vantage point of decades, though, Yitzchak von Schweitzer is now able to survey his past and the questions he wrestles with. After a process of soul-searching that has taken years to unfold, he’s decided to share his journey through a self-published memoir.

“For much of my life, I left my Nazi and brief Waffen-SS experience unmentioned as something that could only stir up trouble and rejection for me,” he says. “After all, what choice did I have? Yet I did have a choice; several in fact. I could have chosen otherwise with dire consequences. That would have required a boy with more insight, conviction, and courage than I had at that time.”

But beyond the personal reflection that as Helmut he was part of the Nazi war machine, Yitzchak’s story contains nuance about the bystanders to the Holocaust.

His story is about the millions of Germans who, in a murderous, anti-Semitic state, may not have supported the warmongering, but refused to think about the killing machine that their country had become.

It’s about a whole generation of postwar Germans who scorned as unpatriotic anyone who highlighted the Fatherland’s failings.

And it’s about those rare individuals like Yitzchak himself who felt driven to do the unthinkable even after Nazism’s defeat: leave the German Volk behind to join their victims.

From the vantage point of decades, Yitzchak von Schweitzer, 97, is able to face the questions he still wrestles with

Heirs and Graces

When Yitzchak von Schweitzer stands at his living room window, he sees two worlds and three centuries. Outside is all the bustle of a Jewish neighborhood: front doors do brisk business, children ride their bikes, and parents maneuver large family cars through the streets.

Inside, behind him, 19th-century Austria lives on. Stern men in tail coats and women in bonnets gaze down from picture frames. A portrait of three young children from the turn of the last century dominates the wall. An imposing mansion, Schloss Gneixendorf in Lower Austria, is visible in a black-and-white photograph.

The von Schweitzers’ ancestral estate provides the backdrop for the opening scene to Yitzchak’s odyssey.

A chateau with a clock tower, outbuildings, and large grounds, the Schloss had stood for three centuries by 1926, when Otto and Margeritha von Schweitzer had a second child, whom they named Helmut.

The newest addition to the Schweitzer dynasty arrived into a once-wealthy family who had come down in the world. Otto was the mayor of Gneixendorf, a village whose residents still referred to him as “Herr Barron” in deference to his family’s historic standing, despite the abolition of aristocratic titles.

Otto himself was a keen farmer who brought in American agricultural methods in an ultimately failed bid to revive the family’s fortunes. The couple also rented out rooms to visitors as a source of extra income.

For Helmut, who became the heir after his older brother Gottfried drowned, life at Schloss Gneixendorf meant a staff of domestics and lots of time spent with younger sisters Rosemarie and Irmingard.

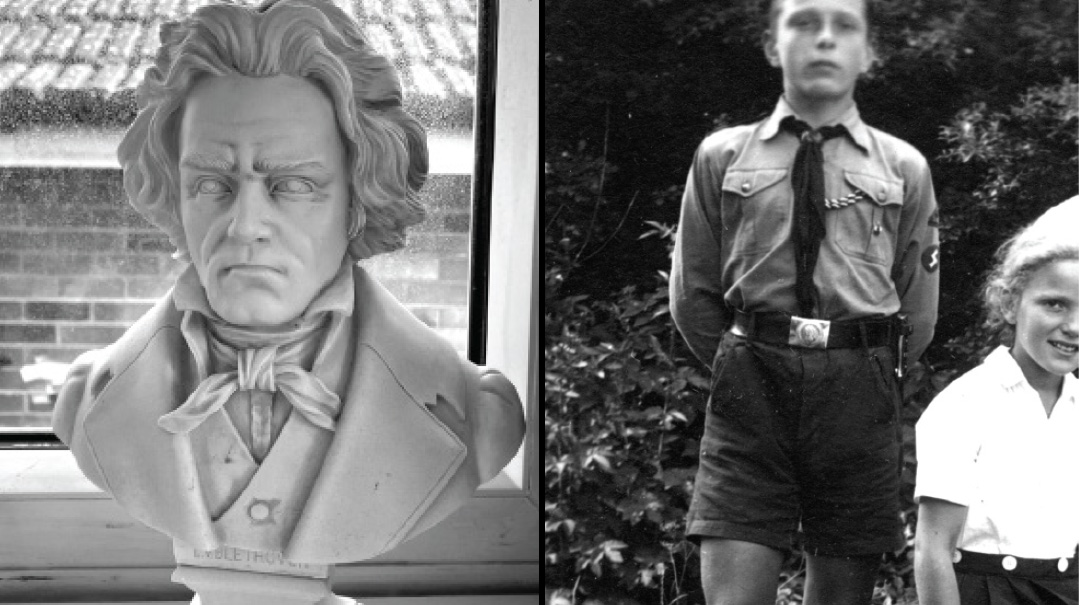

A white bust of Ludwig von Beethoven, which now sits in Yitzchak von Schweitzer’s London home, is testament to the link between the composer and the Gneixendorf mansion. A century before Yitzchak’s birth, the Schloss became the property of Johann von Beethoven, Ludwig’s brother.

The composer stayed at the manor, where he completed his final published work. That connection was enough to turn the Schweitzer home into a place of minor pilgrimage, with slightly comical results.

“We occasionally experienced visitors driving up in big, flashy American cars, asking to see ‘the Beethoven room,’ ” recalls Yitzchak. “They quickly left, embarrassed when they were shown into our toy-strewn first-floor nursery, with only the bust of Beethoven perched on top of the wardrobe as evidence of the connection.”

Little Helmut loved to spend time in the great outdoors, rambling around the countryside on his own for hours on end, and returning with a bunch of wildflowers.

On one of these excursions, he had his first interaction with Jewish history, in the shape of an old cemetery in Krems, a neighboring town whose medieval rabbinate included Rav Aharon Blumlein, uncle and rebbi of Rav Yisrael Isserlein, the famed author of Terumas HaDeshen.

“Along a stretch of old Roman road was the forgotten Krems Jewish cemetery, which was completely overgrown in bushes and nettles,” he says. “We kids had no idea what it really was, but for me, it later became a pointer to the many precursors of a Jewish presence in my life.”

Photo of the ancestral mansion

Early Loss

The death of his mother when Helmut was just shy of four years old — an event seared into the boy’s mind — provides a glimpse into the kind of home and society that he was raised in.

“Five weeks after my sister Irmi’s birth,” he recalls, “I was awakened in the middle of the night by Dad and led to our parents’ bedroom. My mother, whom we called Mutti, was lying there on the bed. I bent down, and she kissed me on both cheeks. Not a word was spoken before Dad took me back to my bed.”

That was the night his mother died of blood poisoning. But typical of an era when children were expected to cope, the little Schweitzer children were not told about their mother’s death; she simply disappeared.

Even after their father Otto remarried two years later, giving the children a new mother whom they called Ulla Mutti, Helmut and his younger sister Rosi tried to preserve their birth mother’s memory by gazing at her portraits and holding on to her personal objects.

Their mother’s diary sheds light on the anti-Semitism that bedeviled Austrian society. Gritta von Schweitzer had kept notes of what she read from 1919 until the end of 1929, including a book titled The False God, by Theodor Fritsch, a virulently anti-Semitic polemicist of the 1920s and founder of the Nazi Party’s political forerunner.

Despite the deep roots that anti-Semitism had in Austrian and German society — soon to propel a Jew-hating Austrian corporal to lead Deutschland — Helmut’s mother disagreed with the anti-Jewish zeitgeist.

She’d befriended Baby Schmidt, a Hungarian Jewish woman who’d married a local, and so she had no patience for Fritsch’s arguments.

“There should be no need to hate when we are faithful to what is good for all of us,” she wrote.

Such tolerance was noticeably missing when the von Schweitzers moved to Germany in 1935, prompted by the family’s financial woes. Despite Otto von Schweitzer’s experiments with advanced American-style agriculture, the Gneixendorf estate fell victim to the Great Depression.

The solution was to leave rural Austria and head for a better life in neighboring Germany — home to Ulla Mutti’s family. Ulla’s father was a lung specialist, whom the children were told to refer to with Teutonic ponderousness as “Professor Dr. Onkel Grosspapa” — the “uncle” denoting the lack of blood relationship.

So, the Schloss was sold to a prosperous Vienna family and the von Schweitzers got on a train to Frankfurt.

As they approached the border, the children received an unpleasant lesson about Germany’s turn for the worse. It came via Rosi von Schweitzer’s doll, which — unusual for Europe at that time — was a dark coffee color. It had been given to her by Baby Schmidt, the Hungarian Jewish family friend back in Gneixendorf.

As the train rolled toward Germany, the children’s stepmother unwrapped an expensive white doll with blonde braids and blue eyes and tried to persuade Rosi to part with her beloved doll in exchange for the Aryan-looking one.

When the little girl obstinately refused, her stepmother tried persuasion, but when that failed, her father Otto did something uncharacteristic: He resorted to force, snatching away the black doll, leaving Rosi crying bitterly.

“Later I learned that the German border police would probably have confiscated the dark-skinned doll,” says Yitzchak, “and we would certainly have made a bad impression with the German authorities. We already had to prove our racial purity according to the standards of the German Reich, with papers going back over four generations.”

A bust of Beethoven, and a picture of Helmut in Nazi days are Yitzchak’s link to a past that, at some level, still lives on

Seeing Evil

The von Schweitzers’ first encounter with official German racism inaugurated the period that, in light of Yitzchak’s journey toward Jewishness, looms largest.

It’s a period in which then-Helmut went about a normal teenage existence in Hitler’s Germany, in a family that seems to have been willfully oblivious to the growing climate of hate.

Over the coming years, there were glimpses of the worsening condition of Jews in Germany, and the pervasive Nazi propaganda and anti-Semitism were impossible to ignore. Yet, says Yitzchak, in the von Schweitzer household, what they called “politics” wasn’t discussed.

Instead, any mention of anti-Semitism or the Nazi program was left at the door in favor of familial harmony.

“My father’s older brother, Uncle Georg, was an early member of the Nazi Party and, after the war, a convicted political criminal. But we had no idea what he did, because it was something that we didn’t talk about. Family peace was always achieved at the cost of unspoken and unresolved tensions.”

The new Germany was rearming and educating the next generation for their part in the coming struggle. As part of the national effort, the Nazis encouraged farming, which suited the von Schweitzers, who bought a farm in the central German state of Hesse. For 11-year-old Helmut, there was the Jungvolk, the Hitler Youth’s junior division.

The Hitler Youth gave the Austrian émigré the chance to see the hero of German-speaking peoples: Adolf Hitler himself, who visited Kassel, a district town.

“As a long procession of black Mercedes cars passed by us,” von Schweitzer describes, “our Fuehrer stood upright next to the driver in his brown uniform, stony-faced, looking neither left nor right. We stood silently at attention and looked at him in awe — the leader of the whole German Reich was passing by a mere three meters in front of us! What greater honor could there be, being briefly so close to him?”

The adulatory encounter with Hitler wasn’t the only meeting with a high-ranking Nazi. In 1940, with Germany at war and father Otto in army service, Stepmother Ulla took the rest of the family to her new workplace, managing the household of SS-Obergruppenfuehrer and Agriculture Minister Herbert Backe.

Over the New Year’s holiday of 1940, Helmut joined his stepmother and younger siblings at the Backe family. At dinner, the kids sat at the bottom end of the large table listening to the great man speaking passionately about the aspirations of German agriculture after the victorious war.

“Little did anyone know then that in the following years, this man would implement ‘Operation Hunger’ following the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union,” says Yitzchak. “The program aimed to starve millions of Slavs and Jews, diverting Ukrainian food for the benefit of the invading army and preparing to settle the population of greater Germany in the cleared area.”

The encounter with Backe — who committed suicide when awaiting trial at Nuremberg in 1947 — is notable in that it’s an instance of the coded language that was a feature of Nazi official talk about the Holocaust.

Although no one could be under any illusions about their genocidal anti-Semitism, the Nazis’ exact plans for genocide would not have featured as dinner party conversation.

But in a Germany where the sizeable prewar Jewish community was Hitler’s first victim, it was impossible for ordinary Germans not to be aware of their country’s dreadful actions.

As late as 1941, through his Hitler Youth work, Helmut encountered what may have been terrified Jews.

The encounter took place in Wiesbaden, capital of the state of Hesse, where his step-grandparents, the Roepkes, lived. One of the only able-bodied boys in the district to be allowed to complete high school and defer military service, Helmut rose through the ranks of the Hitler Youth, eventually becoming a Stammfuehrer, leader of approximately 1,000 boys from ten years old to call-up age.

Assigned Jungvolk leadership in a more deprived part of town, Helmut decided to collect money in his grandparents’ upmarket district.

“Several times the residents were clearly upset seeing me in my neat Jungvolk uniform as they opened the door to my knock. They either slammed the door in my face or threw some coins out in the street before firmly closing their doors.

“Puzzled, I asked Grossmama Roepke about this. She suggested that these people might be Jews afraid of the Nazis.”

Two years later, another brief encounter gave Helmut a close-up view of the Nazis’ Jewish slave empire.

The Kluges — a family of wealthy textile industrialists — were cousins of Helmut’s mother, Gritta. They were cosmopolitan, having had a prewar relationship with the British manufacturers of their machinery, and spoke openly about the failures of the Hitler regime.

But that relative moderation went only so far; their factories were sustained by Jewish slave labor. So on a visit with his Uncle Hannes Kluge to one of the factories, Helmut came face-to-face with the workers wearing yellow stars.

“A girl stared at me,” recalls Yitzchak, “and I stopped and stared back.”

In 1944, Helmut joined the Waffen SS. Although he knew there was “something sinister about Himmler with his security services,” he and fellow soldiers, who were fighting on the Russian front, didn’t actually know about the atrocities of the Holocaust until they read about it in the postwar papers

Nazi Ranks

Having avoided the draft until this late in the war, it was social pressure that finally brought Helmut to the front lines. In the 1944 high school year, he was the only fit male in the whole district to take the Abitur high school graduation exam.

There was no string-pulling involved; German bureaucracy had simply marked him as a successful student whose draft should be deferred. But that led to awkward questions and social pressure: “People on the bus and in the street would ask me what was wrong with me. I looked healthy. Why was I not at the front?”

Worn down by the constant questioning, Helmut decided to take the plunge before he was called.

“One day in 1944, an elite motorized Waffen-SS band arrived in the village playing cheery tunes to a gathering crowd. As I was chatting with the band members, they told me about the camaraderie among the ranks and their sense of purpose, without the tedious parades and drills of the regular army.

“Yes, I could choose which branch I wanted to join. Yes, I could join the tank regiment. My deferred call-up? No problem. I signed up: It seemed to be worth a try.”

The very name of Heinrich Himmler’s SS — suppliers of the death camp guards and Einsatzgruppen killing squads that slaughtered Jews across Eastern Europe — evokes horror.

The Waffen SS was Himmler’s fighting force (Waffen means “weapon”). But while it was a major component of the German armed forces, ballooning to 38 divisions, and fighting in some of the war’s fiercest battles, the Waffen SS perpetrated war crimes on both Eastern and Western fronts. It played an extensive role in the Holocaust, including the brutal liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto.

In that light, it seems difficult to credit that a recruit would have been unaware of the Waffen SS’s savage reputation.

But as Yitzchak von Schweitzer says, these issues weren’t discussed in polite company at the time. “Although I knew there was something sinister about Himmler with his security services, I didn’t know about the Holocaust until I started to read about it in the postwar British papers.”

Helmut in his British Army uniform, navigating postwar London and preparing to assimilate into British society. “I was leaving the guilty sphere for the realm of the rightful accusers”

Forward March

Waffen SS recruit Helmut von Schweitzer reported for basic training in Riga, Latvia, in a German army that was on the verge of collapse, buffeted by the Allied war machine from the outside and eaten away by corruption and rivalries from the inside.

The internal meltdown was exacerbated by the attempt on Hitler’s life by staff officers led by Colonel von Stauffenberg, which took place on the day in July 1944 that the new recruit’s call-up papers arrived.

In the chaos, von Schweitzer’s cohort was shipped around aimlessly by train and boat for six weeks before their basic training began.

Much time was wasted with guard duty over nearby Soviet prisoners of war, and stealing potatoes and turnips from nearby farms to supplement rations.

Officially an armored regiment, there were no tanks — only one artillery piece mounted on a platform, which the green soldiers got to fire once.

In March 1945 — less than two months before the war’s end — Helmut and a squad of about 100 men were sent off to fight the Russians, by now only 60 miles northeast of Berlin.

It was difficult to imagine that this was part of a tank regiment. It had come down to foot soldiering, which ruled out even the use of machine guns, which were too cumbersome, even if ammunition could be found.

For three weeks, von Schweitzer’s detachment did nothing besides try to fend for themselves at their forward base amid the collapse of the German supply chains.

But then in mid-April — two days short of his 19th birthday — the play-acting turned into real war for the new recruit. Von Schweitzer’s detachment of about 20 soldiers was loaded onto lorries and driven down to the nearest contact point with the Red Army, on the Oder River.

As Hitler’s Thousand Year Reich imploded, the vaunted German military was reduced to sending von Schweitzer into battle with a rifle from 1914. Red Army artillery fire lashed the green soldiers as they dug foxholes along the riverbank and awaited the onslaught.

After almost a week fending off cross-river raids and conserving ammunition, with no food reaching the German positions, the Russians struck as an amphibious tank began crossing the river.

The defenders began firing their rifles at the Russians, who threatened to overrun the foxholes. Helmut’s platoon leader, a 20-year-old baker from Bremen called Horst, loaded his Panzerfaust, an early anti-tank bazooka, and fired.

The round hit the tank, which sank, and with it died the onslaught, as the Russians fell back to the other riverbank. Yitzchak discovered a dead Russian three meters away from his foxhole. In the Russian’s pocket was a bread crust, which von Schweitzer wolfed down — the first morsel he’d eaten in four days.

Turning to Horst in the next foxhole, he saw a terrible sight: the troop leader’s back had been flayed to the bone by the rocket’s hot exhaust, and he lay dying in terrible pain.

The next day at dawn, von Schweitzer awoke to the sight of the Russians a few hundred meters away. They’d managed to cross the river, and the Germans faced capture and possible death if they didn’t escape.

“Without thinking, I took command. I yelled to the men, ‘The Russians are coming — follow me!’

“By that stage, I was just determined to escape and prevent the death of my comrades. I was the youngest of the squad, but because I spoke with such authority, they obeyed, and we began to escape to the west, toward the Americans.”

Identity Change

Almost as soon as von Schweitzer’s group of ragged escapees reached American lines, the war was over. As a Waffen SS member, Helmut was interned in a separate camp from normal Wehrmacht soldiers. He soon discovered just how perfunctory the Allied Nazi-hunting effort was.

Interrogated by a young American officer, von Schweitzer was ready with the right answers.

“Hitler? The greatest war criminal. The war? The greatest crime against humanity. The Nazi party? A band of evil fanatics.”

“The officer nodded his approval,” says Yitzchak. “I was dismissed before I even had finished what little there was to tell of my past. He did not even ask me why I had volunteered for the Waffen SS.”

When the British took over control of the POW camp from the Americans, von Schweitzer’s metamorphosis from suspected Nazi war criminal to British citizen began.

What’s noteworthy about the change — indeed, Yitzchak von Schweitzer’s entire evolution — is how completely he was able to slough off his past and adopt a new identity. The 19-year-old started with an advantage in the English skills that he’d gained from early lessons at Schloss Gneixendorf with the family’s British nanny.

Those language skills and his leadership qualities meant that Helmut became a translator for the group, and was chosen to be part of a group of German POWs shipped across to London to make the city’s blitzed streets safe from unexploded German bombs dropped during the war.

Over the next three years, he’d work in England, clothed in British Army uniform, navigating postwar London and preparing to assimilate into British society.

That aim was helped along by two achievements: One was enrollment in the London School of Economics (LSE), and the other was his marriage to his first wife, a local girl.

Yitzchak remarks on his own success in distancing himself from the losing side, and effectively, joining the victors. “By settling in Britain, I was leaving the guilty sphere altogether for the realm of the rightful accusers.”

Conversion Course

In Yitzchak von Schweitzer’s collection, there are two photographs that symbolize the stark contradictions of his metamorphosis. In one there’s Helmut, the handsome Hitler Youth leader, pictured before being drafted to defend Berlin as the Red Army crossed the Oder River. The second is of Yitzchak, now a patrician, white-haired figure clad in tallis and tefillin, receiving an aliyah in a local shul.

The third stage in the journey between those two poles was conversion, which took place decades later, when Yitzchak had been settled in South Africa for a number of years. Unlike some geirim, whose story involves some blinding flash of clarity that led them toward Judaism, the journey from Helmut to Yitzchak was a gradual process, formed of many different encounters.

One early incident that would only gain its full import in hindsight was his birthday in 1948.

“I was born on Rosh Chodesh Sivan 1926, and on my birthday in 1948 — when I was still working in bomb disposal — I heard big news: that a Jewish state had been declared.

“At the time, I felt that it was significant, although I didn’t know why it was for me, personally. But the coincidence of my birthday became one of the long series of pointers drawing me close to the Jewish People.”

In the journey toward Orthodox Judaism, Yitzchak wasn’t alone; it was a joint endeavor of his second wife.

Pam, now Rivka, was born to working-class parents in the East End of London, where Jewish neighbors had stepped in to help the family when they hit hard times. Dissatisfied with her Christian upbringing, she spent years feeling unconnected to the various denominations that she experimented with.

Although her mother avoided pointed questions on the topic, Rivka suspected that she had Jewish roots — a fact confirmed recently by DNA test.

When Pam, as she was then, introduced her fiancée to her mother, the older woman reacted to his nationality with dismay: “But he fought for the wrong side!” was her response.

The von Schweitzers’ move to apartheid-era South Africa in 1971 came after a stint working in retail, followed by a move to Germany on behalf of ITT, an American corporation.

Moving to Waverly, a Johannesburg neighborhood with a strong Jewish presence, was the next fateful step in their path to Jewishness: the local Orthodox shul turned out to be located at the end of the von Schweitzers’ road.

Over time spent working with Jewish businesspeople, a sense of identification with the Jewish community and their way of life grew.

As with the rest of the journey, there was no single point of sudden epiphany that led the couple to Judaism. But they had a strong sense that in both of their lives, there was the hidden hand of G-d at work.

“There were so many events in our backgrounds that pushed us toward Judaism — we felt that we had no choice but to convert,” says Rivka.

The giyur, which was performed by the Johannesburg Beis Din, included the couple’s two children, Karl and Gretta, then nine and ten years old, respectively.

When the family went to shul on the first Shabbos after becoming Jews, the newly named Yitzchak again felt like a foreign invader.

“How would this great Jewish congregation feel about this past German interloper? How could I, with my past, dare to face them? Suddenly I was shaken by an amazing exaltation, a burst of gratitude and sense of homecoming. We had been invited in, given a chance to prove ourselves.”

South African Stalwarts

Very quickly, the von Schweitzers became stalwarts of the Johannesburg community.

“They were both very devoted to community life,” says Dayan Boruch Rapoport of the Johannesburg Beis Din, who was also the couple’s rabbi at the Keter Torah shul. “Yitzchak would come to Gemara shiurim, they volunteered their time for the community, and gave tzedakah generously.”

Learning the details of Yitzchak’s story over the years, Dayan Rapaport himself was moved. “There are very few people who would have been willing to undertake his journey,” he says.

For Rivka, some moments stand out in their Jewish journey. “The first time that I heard the shofar blown in shul was one of the most moving experiences I’ve ever had,” she remembers. “I had a sudden vision of standing at the foot of a hill, like Sinai. It brought tears to my eyes.”

Shabbos also became a highlight for the couple. “We discovered what a beautiful experience it was to close the door on the week. Before becoming Jewish, Friday night and Saturday meant shopping and running from one thing to another. This is so much more peaceful.”

Many years later, Shabbos is still a highlight. Throughout the week, they collect snippets of reading material such as parshah sheets to read on Shabbos.

In Johannesburg, the couple took a particular interest in shul programming, sponsoring a Shemini Atzeres kiddush that became a community-wide event.

Dr. Robert Odes became a friend in the years following their conversion. “They were warmly welcomed in the kehillah, and contributed a lot to the shul’s upkeep, including painting the building and replacing worn tablecloths, which came naturally to Rivka, since she was in the textile business.”

Moving to Edgware to follow their children in 2016, the von Schweitzers became active participants in a local shul, Netzach Yisroel. Last year, aged 96, Yitzchak celebrated a “second bar mitzvah” (his “first” bar mitzvah was at age 83, 13 years after turning 70; 13 years after that, he celebrated again), at an event that moved shul-goers.

Rabbi Reuven Stepsky, Netzach Yisroel’s rav, says that their unusual dedication has continued in London. “Anything that is tzorchei tzibbur finds them a willing volunteer.”

And Rivka — indefatigable in her 80s — now works 12-hour shifts as a mashgiach for the London Beis Din in a Jewish old-age home in an adjacent suburb, arriving at 6:30 a.m. to start her day.

“I love working there,” she says. “It’s so much more fulfilling than what I did when I was in the textile business — perhaps this is why I was meant to convert.”

Outside In

Decades after becoming Jewish, Yitzchak von Schweitzer still has a strong sense of being a newcomer; he describes himself as a “perpetual outsider.”

That sense is especially strong when he visits Austria and Germany. “My family could never understand my conversion, and in typical von Schweitzer tradition, it was basically not a topic of conversation between us. I became something of a stranger.”

That attitude is connected to the reality that the wartime generation has never given an honest account of what was done, and continues to avoid the subject.

“In general, there’s a sense among people of my generation that the war is something that is impolite to talk about. That means that my book wouldn’t be publishable in Germany, because people would feel that it’s somehow unpatriotic.”

That attitude was pervasive in the immediate aftermath of the war. In the British prisoner of war camps that he was held in after Germany’s surrender a few weeks later, Yitzchak reports, there was a blanket denial of knowledge of the country’s crimes.

“Newspapers found their way into the camp and were passed from hand to hand. They were full of stories of German war crimes and concentration camp atrocities. The first reaction of us ex-soldiers was righteous disgust at these vile reports. What had really happened was not the issue. ‘We must stick together,’ people said.”

As the erstwhile heir to the bankrupt Austrian baronial estate gazes out over the hum of London Jewish suburbia, his ancestors looking down silently from their paintings, Yitzchak von Schweitzer reflects on his own far-fetched transformation.

“As a Jew today, I feel sick about what happened. But taking a different path back then would have required more courage than I had. Instead, I was ambitious, and intent on surviving.”

Almost 80 years after leading his fellow soldiers away from Germany’s war on the Oder, the country no longer has a claim on Yitzchak von Schweitzer’s loyalties. From that moment on, he’s lived with his own sense of destiny.

“From when I stepped forward to save my squad from the Russians, I felt a sense of mission. Over the years it gradually became clear to me that it was a Jewish mission.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 972)

Oops! We could not locate your form.