One in a Million

Mourning Rabbi Moshe Grylak, founding editor of Mishpacha

“A million children were killed during the Holocaust. For some reason, Hashem chose to spare me. Surely I’m meant to do something for Him in return!”

That was the refrain Rabbi Moshe Grylak’s family heard throughout his life. This week, his 87 years of devoted service came to a close, and there was no doubt that he had fulfilled his mission.

Young Moshe, named for Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzato and buried on his yahrtzeit, survived the Holocaust as a child, first in France and then in Switzerland. Upon the war’s conclusion, he left behind war-torn Europe and settled with his parents and siblings in the fledgling chareidi community of Israel — a country riven by conflict without and within. He learned new languages and a new culture, finding mentors and rebbeim among the gedolim of the era, including the Chazon Ish, Rav Elazar Menachem Shach, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, and the mashgiach Rav Gedalia Eiseman, among others.

With time, he found his calling as a pioneer in both the kiruv sphere and the world of chareidi journalism, as an acclaimed master of the written and spoken word who conveyed ancient truths in a current medium.

Rabbi Grylak was one of the earliest lecturers of the Arachim kiruv organization; he could connect with even the most skeptical of secular Jews, and welcomed any question without fear or cynicism. His Shabbos table accommodated any number of guests, many of whom went on to embrace full mitzvah observance. When his family was still young, they moved to São Paulo, Brazil, as emissaries of the Jewish Agency to draw Jews closer to their heritage. The new language and new setting could not deter him from conveying his message.

Even as he gained a name for his public speaking, he also gained a following for his writings. In a pioneering move, he took on a weekly column for the secular Maariv paper conveying thoughts from the parshah to the Israeli public — who lapped up his insights thirstily, recognizing the enduring truths that lay in his very current prose.

In the summer of 1986, Rabbi Grylak was invited by Rabbi Shmuel Chasida to join the editorial staff at the Hebrew language Yated Ne’eman. When Rabbi Chasida left his post three months later, Rabbi Grylak was appointed by Rav Shach as the editor-in-chief. In that capacity, he brought his talent for writing and his skill for reaching the reader to a new audience.

In 1993, he was hired as editor-in-chief of Mishpacha Magazine, which he nurtured and developed to become the most widely read weekly publication among the Orthodox community. Throughout his many years at the helm of the publication, he maintained his kiruv activities, mentoring a new generation of mekarvim, and succeeding in finding the right lexicon for changing times.

Rabbi Grylak was propelled in all his endeavors by a deep inner drive for emes — a drive his readers sensed and respected between the lines of everything he wrote. He was a speaker and editor, a columnist and novelist, a talmid chacham, and keen social commentator — but more than anything, he was a communicator of Hashem’s Word and of Torah values.

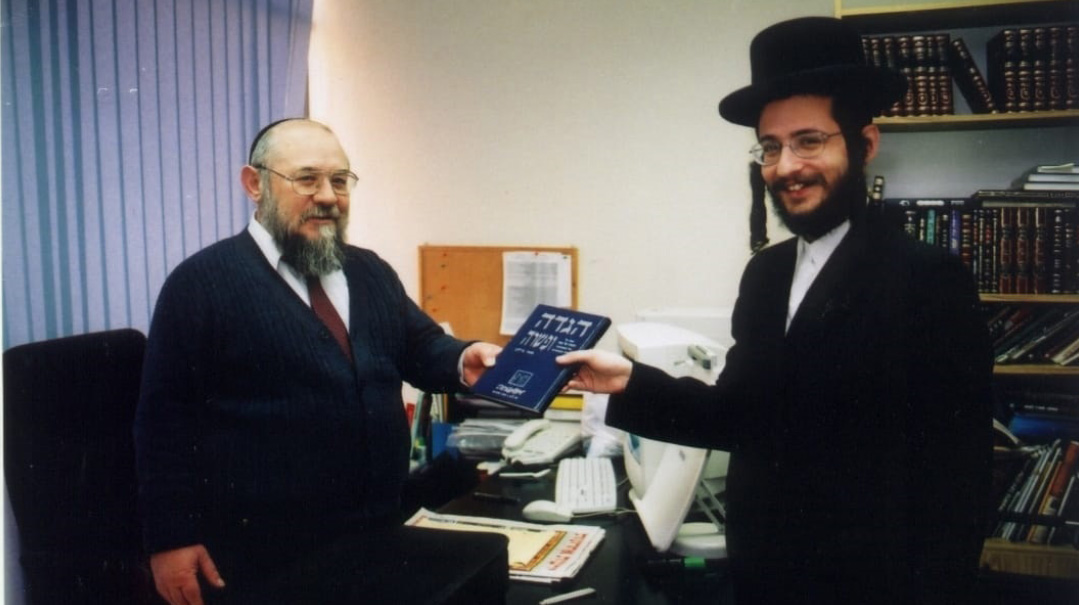

He found the words to relay Torah concepts to a new generation. Rabbi Grylak (seated) greeting Rabbi Menachem Cohen of the Hebrew edition’s rabbinic board as publisher Eli Paley and CEO Yehuda Nachshoni look on

Back to Sinai

Eli Paley

I

spent 33 years with Reb Moshe, meriting to stand beside a great man who was a teacher, a rav, and a mentor.

Reb Moshe was the man who established and laid the foundations of this great enterprise, and who aimed to bring Am Yisrael closer to their Father in Heaven with faith and honesty, with dedication and responsibility.

I first met Reb Moshe in the home of my father zichrono livrachah on a winter day 33 years ago, when I was asked to leave the beis medrash and assume responsibility for running Mishpacha. I had no idea what I was supposed to do.

Already then, as a talmid in Yeshivas Chevron, I read Reb Moshe’s columns, and I sensed how he’d created a new language, a means of communicating the ancient Torah and pouring it into the vessel of our generation.

Reb Moshe viewed the media as a conduit to disseminate Torah ideas to this generation, and made it his life’s mission to do so. In fact, when we were considering where to establish the headquarters of the international edition, he insisted that it be based in Israel: “Ki mi’Tzion tetzei Torah.”

Today we have talmidei chachamim, and we have philosophers and thinkers, and we have roshei yeshivah, but we struggle to find the right language, to take this wonderful gift and convey it to the next generation.

Reb Moshe held that key. He established generations of talmidim, and he generated a language that takes Torah in all its glory and brings it to our generation. He did so in Tel Aviv, in São Paolo, in the pages of Maariv, and in the pages of Mishpacha.

The same dynamic was at play when he wrote about Torah, about Pirkei Avos, and when he dealt with questions of science and emunah. Back when I was a yeshivah bochur, I saw him as a hero, the man who took great ideas and knew how to convey them in our lexicon. I knew that if he were to lead us at Mishpacha, we would have a chance of succeeding.

In the early years of the magazine, Reb Moshe worked largely alone. With dedication, sleepless nights, toil and grit, he sifted word after word uncompromisingly. He was an artisan who wouldn’t quit until he found the precise word for the message he wanted to convey.

The Mishnah says that Mordechai was called Pesachya, because he would open things [pasach] and make them accessible, with his fluency in 70 languages. Reb Moshe translated the Torah into various languages without altering it even one iota.

And he did so without fear. As it says in last week’s parshah, “And Moshe approached the fog where Hashem was.” After our nation emerged from the crematoria of the Holocaust battered and beaten, after so many people had lost their emunah, Reb Moshe visited Auschwitz to search there. “Moshe nigash el ha’arafel asher sham ha’Elokim.” And there he found Him — in the great hester panim, the darkness.

In the postwar decades, when the question “Where was G-d in the Holocaust?” became a challenge to many people’s faith, Reb Moshe was the one to demonstrate that, on the contrary, the unfathomable suffering revealed Hashem’s existence, rather than challenged it.

“If the Torah predicts a time of intense suffering and hester, and it indeed comes to pass in the exact way predicted — can there be a greater revelation of Hashem’s presence that that?’ Reb Moshe wrote.

Reb Moshe found emunah even in the darkest of places because he sought it with real, genuine effort. He saw his survival as a mission, as an obligation to convey faith to the coming generations.

Gadol shimushah yoser mi’limudah. Reb Moshe’s experiences serving gedolei Yisrael became his guiding light in every sentence, every word, every column that he wrote.

Lo kein avdi Moshe — B’chol beisi ne’eman hu.

Rav Grylak used the power of his pen in multiple forms — philosophy, current affairs, and storytelling — to relay timeless lessons.

But it wasn’t just skillful writing. He wrote from the heart. He saw himself as a shaliach tzibbur, a representative of the public, who took upon himself the responsibility to bring the voice of Torah to us.

As a founding father of Israel’s teshuvah movement, he played a crucial role in developing both the organizational frameworks and ideological content that exist today to convey the truth of Torah and emunah.

He brought us back to Sinai. He took us back to the days of Creation, addressing the major questions of humanity and science without fear. He searched in the words of Chazal for the eternal answers to the questions of our generation.

He was a beacon for us, a guide, a rav, a father. Now, with his passing, we are all the poorer.

No Better Mentor

Rabbi Eliyahu Gut

I first encountered Rabbi Grylak’s name when I was a boy, as I heard it from my grandmother, Mrs. Shulamis Fradel Greenbaum-Osterzetzer a”h, when she spoke about her youth in Antwerp before the Holocaust. She, and her brother Reb Shmuel Osterzetzer ztz”l, established the Jesode Hatora institutions, and she occasionally mentioned “the Grylaks.”

Rabbi Grylak’s name was also mentioned in my childhood home as the editor of the Nitzotzot magazine, which led to a revolution in the field of Jewish hasbarah, for those both near to and far from their heritage.

Many years later, in 1994, a few years after I married, and I joined the team of Manof — the Center for Jewish Hasbarah, headed by Rabbi Mordechai Arnon z”l, and managed by ybl”ch Rabbi Danny Nasi. One of the members of the board, alongside Rabbi Mordechai Neugroschel, Rabbi Shalom Dov Srebrenik, and Rabbi Yisrael Eichler, was Rabbi Moshe Grylak.

Two years later, I found myself at the Mishpacha office at Ki Tov 8. A 50-something-year-old man of short stature with a big smile emerged from the room, and in our conversation he began to tell me about the connection between our families.

It may have been Rabbi Grylak’s childhood years in Antwerp, and later as a refugee boy living with a family in my hometown of Zurich, or perhaps our similar European background and languages (German, French, and of course, Hebrew and Yiddish) and general knowledge — to this day I can’t put my finger on it. But I very quickly found myself working at Mishpacha from 1996, and often, we were on the same wavelength.

The batei medrash that influenced our lives were similar. He was a talmid of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach and Rav Gedalia Eiseman, and while I didn’t merit to learn from them directly, I was raised under their influence, secondhand. Likewise, because of his relationships with Rav Shach and Rav Steinman, and as someone who saw the Chazon Ish as a child, and was involved in recording his biography — I saw Rabbi Grylak as another link in the chain of handing down the right hashkafah.

As noted, we come from similar backgrounds — not the same, but similar. So there were times when we had different reactions, and that was just fine. That is what Rabbi Grylak tried to convey. In conversation with him about current events, such as before he wrote his weekly column, “Point of View,” we were largely, if not always, in agreement about the message, although not always about the way to present it. But the mission remained the same, as did the tools to achieve it. Write, publish — it has an influence. On adults, and — perhaps most importantly — on the youth. I personally heard from gedolei Yisrael, both who are with us today, and those who are no longer here, about the importance of publishing articles faithful to Torah. Regretfully, a newspaper article sometimes has more influence than all the mussar shmuessen combined.

To this day, I always remember the instructions Rabbi Grylak gave me: “Always remember that it’s possible that the newspaper will fall into the hands of Yossi Sarid and Shulamit Aloni (the Lapid and Liberman of those days when it comes to hating chareidim, albeit much more intellectual than today’s personalities), for example in the waiting room of a doctor’s office. And they will read your article, and through it, they will be exposed to the chareidi world and the world of mitzvah observance. So make sure you do it properly.”

Later, I stepped into his huge shoes as the editor of the Kolmus Torah periodical, and as an editor of the magazine, and only then, did it once again become clear to me how much I had learned from him on a personal level, about interpersonal relationships, how to manage the writers and to guide them. How to convey delicate messages of constructive criticism, and how ultimately, to make decisions even if they are difficult and unpopular. I don’t think I could have wished for a better mentor.

Rabbi Eliyahu Gut is the Secretary of the Rabbinic Board of the Hebrew Mishpacha.

“His lunchtime conversation ranged from prewar Zionism to an encounter with the Chazon Ish to the sports interests of estranged Jews in Brazil.” With Rabbi Ephraim Galinsky

He Created the Language

Rabbi Efraim Galinsky

INrecent months, I had the great privilege of spending many hours with Rabbi Grylak in an attempt to retrace the footsteps of his multifaceted life since his very early childhood years during World War II.

Rabbi Grylak was one of those rare people who could have lunch with you and candidly recall sitting on the lap of the legendary prewar intellectual Zionist baal teshuvah Dr. Nathan Birnbaum (probably the last remaining person on earth who met this giant of a Yid), and continue with a description of himself as a child hearing a live broadcast of Hitler yemach shemo ranting against the Jewish people. He would then describe a meeting with the Chazon Ish ztz”l, and end off l’havdil rattling off the names of popular South American soccer players he remembered from his years as a shaliach in Brazil.

Rabbi Grylak’s pioneering kiruv and hasbarah efforts had — and continue to have — a tremendous impact until this very day. In one discussion, Rabbi Grylak described his late-hour meeting held decades ago with two of his colleagues, ybl”ch Dr. Tzvi Inbal and Dr. Shalom Srebrenik, in order to hammer out the syllabus for the first Seminarim (weekend Hotel Shabbatonim) geared for the academic secular populace. These programs eventually mushroomed to the famed seminars of Arachim and many other kiruv organizations in Eretz Yisrael and abroad. As part of these efforts, Rabbi Grylak initiated a weekly hashkafah column in the widely-read secular Maariv newspaper. The column, titled “Da et Yahadutecha” (Know Your Judaism) was enthusiastically received all over Israel, and many have testified that this is what caused them to make a change in their life. Rav Moshe Shapira ztz”l once commented that these columns were the first successful attempt in translating lofty Torah concepts into modern Hebrew.

At the levayah late Tuesday night, Rabbi Mordechai Neugroschel, a kiruv phenomenon in his own right, said that all kiruv lecturers are Rabbi Grylak’s talmidim, whether or not they knew him personally, because he is the father of the field. Reb Moshe, he said, “created the language of kiruv” that is used until this very day.

Another herculean effort of Rabbi Grylak was the production of a high standard full-color magazine titled “Nitzotzot” (Sparks), which was a trailblazer in accessing the secular (and eventually the religious) public with high-level content relating to Torah and science, emunah and hashkafah.

Aside from his great efforts within the world of kiruv (both through the written word and through extensive public speaking), Rabbi Grylak channeled many of his efforts inward in creating kosher and inspirational reading material for the frum public in Hebrew and in English. Originally tapped by Rav Shach as editor-in-chief of the newly founded Yated Ne’eman, Rabbi Grylak later took the helm of Mishpacha Magazine and had led us for close to 30 years.

Years ago, a well-meaning individual once approached Rav Elyashiv ztz”l with a suggestion to raise awareness about a thorny problem relating to the frum community. Rav Elyashiv responded, “If this issue would be raised by Reb Moshe Grylak with his characteristic sense of achrayus it may be done, but no one else today has the necessary qualities for such a task.”

Rabbi Efraim Galinsky is a member of Mishpacha's English and Hebrew Rabbinic Boards.

Keen Mind, Gifted Pen

Yonoson Rosenblum

TOdescribe Rabbi Moshe Grylak as the greatest Torah journalist of the last two generations is like describing Warren Buffett or Bill Gates as a millionaire: It does not begin to do justice to how far he towered over all the rest of us.

For one thing, he enjoyed the absolute confidence of the leaders of the generation. As a young man, he was entrusted with gathering most of the material for Pe’er HaDor, the classic five-volume work on the Chazon Ish. When the leader of the generation, Rav Menachem Elazar Man Shach, decided to open a newspaper in 1989, it was natural that he tapped Rabbi Grylak to be the founding editor.

Later, as the founding editor of the Hebrew language Mishpacha, he gave instant credibility to the new magazine, and when an English edition started almost 20 years ago, his brilliance and eloquence gained a new English-speaking audience.

At a time when the mainstream Israeli press was hermetically sealed to writers from a Torah perspective, he began writing a two-page spread for Maariv, then Israel’s second largest circulation paper, every week, in which he linked the parshah and current events.

By any measure, he led an extremely eventful life. As a young child, no more than six I believe, he had the responsibility of leading a younger sister to Switzerland, across a border patrolled by gendarmes only too eager to send Jews back to their fate.

He learned for years in Ponevezh and Kol Torah, but unlike practically every other yeshivah bochur of the generations after him, he also saw combat during the Sinai campaign. His wife and he spent two years teaching in Brazil as shlichim of the Jewish Agency, and the country subsequently provided the setting for one of the thrillers he penned under the pseudonym Chaim Eliav. As a speaker and thinker, he was one of the early pioneers in the Israeli kiruv movement and highly sought out.

There was simply nothing he could not do with his pen: a commentary on the Haggadah; analyzing current events from a Torah perspective; sharing memories of the greater Torah figures with whom he was close; even the aforementioned thrillers. The only tragedy is that he never had the financial security to devote himself to major projects he had long hoped to undertake — e.g., a biography of Dr. Nathan Birnbaum.

His gifted pen, however, would have been wasted had it not been linked to a keen intelligence and almost boundless intellectual curiosity. He could write about everything because he read about everything. And he was always eager to meet those who could expand his intellectual horizons.

Those of us who treasured his company and saw in him a role model are left bereft. But we still have our memories, and his example, and the huge body of writing he left behind to guide us.

Yonoson Rosenblum is a widely read author and columnist.

He found the elusive key to communicate ancient values in modern terms

Farewell to the Capitán

Faigel Safran

Although he was already in his later years when we met, Rabbi Grylak was incredibly up to date. He just got it. He understood everything, including, to my great surprise, me.

When I joined the newly launched English language Mishpacha in 2004 as Managing Editor, I wasn’t coming from another high-powered position. I was coming from my kitchen after 15 happy years of being an akeret bayit. Why they offered me the job remains a mystery to me to this day, but it was all worth it to have merited Rabbi Grylak as my mentor.

He understood all the dilemmas, all the crises, all the conflicts that would come up in an editor’s day, and would sum it all up in a pithy word or two. But he had a trick: he never let on what he knew. He’d wait for you to realize on your own that he understood you, believed in you, got you. And when the penny eventually dropped, you’d look at him and he’d give a little nod of his head, as if to say, “Finally!”

He was one of the biographers of the Chazon Ish, one of the founders of the Yated Ne’eman, one of the first lecturers for Arachim. He was an innovator, original thinker, a brilliant journalist and a fabled novelist.

After I left Mishpacha, I, too, became a novelist. Rabbi Grylak claimed that I could never write a book because I was too impatient (true), so that problem was solved by writing serial stories. Rabbi Grylak would speak from time to time about his escape from Belgium into Switzerland during the war, that his parents had entrusted him at age six to lead his younger sister to safety. “I was the capitán!” he would say. And then, sotto voce, “I had no childhood.”

Any writer will tell you that you only need to hear something once for it to end up in a story at some point. The seed was planted, and years later, my protagonist was leading his two younger brothers through Europe to Eretz Yisrael. I never told him about the book, but I guess he knows about it now; I hope he doesn’t mind.

I still remember an editorial meeting. I had been asked to prepare a short talk on a certain somewhat controversial subject. As I stood up shakily, I started my shpiel and I soon noticed an odd look on Rabbi Grylak’s face. After the meeting, I went to stand next to him. You didn’t have to ask him too much; he usually knew intuitively what you wanted to say.

Instead of addressing me directly, he said to the person next to him, sort of gesturing to me, “Can she speak!” I didn’t know it before, but once he said it, I knew it was true. I could speak, I had what to say, and I’d received semichah from the master. It was a good day.

Goodbye, my friend. Please be a meilitz yosher for us. If anyone of us can convince Hashem to bring Mashiach, it’s you.

Faigel Safran is the founding Managing Editor of Mishpacha and a freelance editor and novelist.

Oldest and Youngest

Shoshana Friedman

W

hen I joined Mishpacha’s editorial team, Rabbi Moshe Grylak was the oldest staff member. But I quickly learned that in the ways that count, he was also the youngest.

He was one of the “elder statesmen” of the industry, with a long résumé in publishing and hard-won experience as a prime architect of chareidi journalism. Over the years, he had gained the trust of gedolim and the authority to set policy. I remember asking him about featuring a security expert who was not religious. “When I asked Rav Shach this question…” his answer began.

But his demeanor was anything but elderly. He was a fount of creativity, intensely curious, with a strong sense of adventure. A few years ago, when he was in his early eighties, the editors wondered if he’d consider a trip to Portugal. His eyes lit up. He’d always been curious about the crypto-Jews, he said. After years of reading and researching, what could be better than exploring the story on-site?

The scope of his writing is more varied and original than that of any frum writer I know. He wrote incredibly wise and deep hashkafah columns, colorful travelogues, historical explorations, short stories. He crafted the most vivid personal essays — the two accounts I remember most describe his childhood escape from the Nazis in a dark Swiss forest, and the story of the Bnei Brak shul of his youth, a converted classroom where all the hardened Holocaust survivors broke down during the Yamim Noraim davening. And he innovated the genre of frum thrillers, weaving complex sagas with threads of history, scenes from his own experience living in the Nazi refuge of South America, and characters seeded with his deep understanding of human nature and family ties.

One of the first times I watched him brainstorm was at a Yom Tov planning session many years ago. The editors in the room raised various ideas — a conversation with a rav, a travel piece, an interview with a popular singer. He seemed bored. Then there was a lull and he piped up, “Why don’t you do something different? Give your readers something new, something they haven’t seen! Like maybe” — and we could almost see the wheels turning inside his prodigiously creative mind — “maybe we can do a project on Jewish kingdoms of the ancient world? There were several of them, you know — one even had a Jewish queen! — and it would be so fascinating to read detailed pieces about four or five.” He then ticked off a list of candidates from various historical eras and locations.

That sense of adventure, of opportunity, of open doors was something he instilled in the magazine. His status of talmid chacham (as Rav Mordechai Neugroschel put it at the levayah, he was a talmid chacham chacham — a truly wise scholar), his identity as the face of Orthodox Judaism to generations of mekuravim, and the weight of his responsibility as chief architect of a Torah publication never held him back from exploring new formats or genres. His deep roots were evident — but he was eminently current.

The fusion of tradition and innovation, of enduring values in contemporary packaging, became the DNA of the publication he built. He urged his team to be the “adults in the room,” to produce a magazine with fealty to our mesorah and allegiance to daas Torah, but he also propelled us to innovate and experiment and reinvent.

For Rabbi Grylak, those two identities weren’t a contradiction. He was broad enough to meld them into one, and in doing so he set an example for all of us who struggled to keep pace with the most youthful elder statesman we had ever met.

Shoshana Friedman is the Managing Editor of Mishpacha.

The Value of Every Word

Binyamin Rose

Rabbi Moshe Grylak innately understood the value of every word.

He also appreciated the value of every reader, and knew how to engage them with wisdom and wit.

I experienced this firsthand after joining the English Mishpacha at its inception in March 2004. Rabbi Grylak entrusted me with translating his “Point of View” column, the magazine’s opening piece for many years.

It was an honor, and also an enormous challenge.

Many words and terms in lashon hakodesh get lost in the translation. All the more so with Rabbi Grylak, whose prose was sophisticated and nuanced, and whose lexicon was rich and scholarly. He trained himself to analyze current events through a Torah-true prism, shaped by his hashkafah and unique life experience.

He would submit his column on Sundays, often perilously close to our print deadlines. It could take up to three hours for me to do his column justice in English. At times, I struggled with an idiomatic phrase or concept. Usually he was available for last-minute consultation, but on one occasion, I indulged in some editorial overreach to interlace one of his ideas with my own hashkafah.

Big mistake.

Rabbi Grylak didn’t write in English, but his comprehension was just fine, and when he saw my change in print, he voiced his displeasure. He reminded me that “Point of View” was his column and that I’ve got my own, and he was 100 percent justified. But he didn’t leave it with a reprimand. His secondary goal was to make me a better editor. He explained what he intended to say, and where I had erred. I ended our conversation with a greater respect for a brilliant writer who understood the value of every word and the impact he wanted to make.

I was humbled, but Rabbi Grylak could be humble as well. At times, he had two or three good ideas for his next column. Knowing that in my role as news editor, I was in contact with a wide range of US-based sources, he would ask me which idea I thought to be the most relevant, and he would accept my advice. On the rare occasions when I thought his nuanced observation would be lost on readers outside of Israel, he was also open to feedback.

If Rabbi Grylak learned one or two things from me, I learned so much more from him.

When we inaugurated our first news section, known as Jewish Geography (JG), we would brainstorm almost every Thursday morning. He would stop by my office, or call, and ask what I was writing about. If he thought my topic or my slant was too “Israeli,” he would ask me, in a fatherly but firm tone: “How will this interest a reader in Flatbush?” He wasn’t necessarily suggesting the topic wasn’t of interest but was reminding me to make of it of interest.

He taught us to work under the assumption that because of our lag time between deadlines and distribution, we had to assume our readers were already familiar with the news. Our role was to deliver a Jewish angle and to provide cogent analysis.

Rabbi Grylak was as perceptive and as sensitive as a person as he was as an editor.

Once on an assignment together in Europe, he heard me conversing with some colleagues, and he got the sense I was looking for kavod for my work. He sidled over to me and reminded me my job was to do my job and to be satisfied every time my byline appeared in Mishpacha.

On that same trip, our media caravan was headed to a new location, and I sat in the back of the van studiously scribbling notes so that I could add some color to my article. When one of my colleagues ribbed me for being standoffish, Rabbi Grylak stuck up for me and said, “Leave him alone, that’s the way he works.”

In recent years, our contact was limited to the twice-yearly “toasts” that Mishpacha holds for its team before Pesach and Succos. I missed this year’s Pesach event, but before Succos — the last time I saw Rabbi Grylak — I made sure to thank him for having been a mentor to me. His face gleamed.

That was a kavod he richly deserved and a sentiment that I know would be shared unanimously by chareidi journalists who worked at Mishpacha and elsewhere.

May his memory serve as a blessing for all of us.

Binyamin Rose is the Editor-at-Large of Mishpacha.

Like his old friend Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau (center), he emerged from the ashes of the Holocaust, learned the language and culture of a new country, and became a face of enduring faith

The Final Link

Bassi Gruen

I

sh emes.

That’s the first term that comes to mind when I think of Rabbi Grylak. He spoke the truth, and he lived the truth. Even if others didn’t agree, even if he knew he’d get criticized for it — when he felt a message needed to be shared, he shared it simply and powerfully.

He was fearless, willing to touch topics that others avoided. Ready to show us another way to approach the burning issues of the day. To cajole us into removing our blinders, and look at the larger picture.

He was simultaneously able to view the world with the crystal clarity of a Torah lens, and also to genuinely understand where others were coming from. He could decry painful breaches in Israeli society, and also love every Jew genuinely and fiercely.

He was humble, so humble.

He was a master wordsmith, and yet, at Mishpacha events, when another writer would speak about how to hone the craft, he listened avidly. Never mind that he had been writing eloquent columns before the speaker was born; he was eager to learn from every person in his orbit.

One day he came into my office to speak with another one of the editors. On my desk was a popular self-help book about how to boost one’s productivity. He asked if he could borrow it.

I was dumbfounded. He no doubt could have written such a book. But that’s not how he saw it. Here was a chance to gain knowledge, and he embraced that opportunity. When he returned the book, he shared several insights he’d gleaned, adding his perspectives on the concepts.

He was the ultimate talmid, quoting his rebbeim decades after they’d left the world. Able to sense how they may have approached current issues, to connect advice they’d given him years before to the thorny problems of the day.

He shared the advice of the gedolim of yesteryear, but even more, he shared the stories. The brief encounters, the wry quips, the mundane interactions that he knew were never mundane. And through those stories, he pulled back a curtain and let us glimpse a world that’s vanished.

He was our link to the glory and struggle, the passion and pain of a fledgling Eretz Yisrael, to a tiny band of chareidim desperately fighting to ensure that Hashem’s palace remain a place in which He’d feel welcome. He could give us context to current battles, trace today’s struggles to their tumultuous roots, and offer advice on how to move forward, how to build bridges and mend the ragged fabric of our country.

He was a visionary with one eye facing forward to the future and one eye fixed firmly on the past.

And now he is gone, and that final link has vanished.

Yehi zichro baruch.

Bassi Gruen is a freelance writer and editor who served as former Managing Editor of Mishpacha's Family First publication.

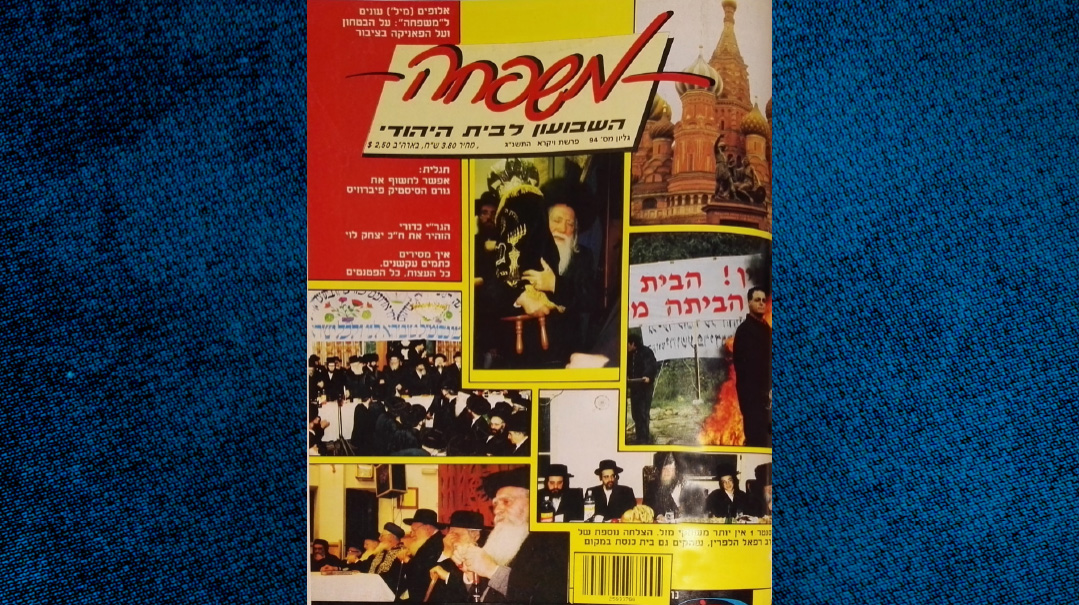

An early edition of the Hebrew-language Mishpacha. He had the vision and journalistic skills to take it into the new era

He Thought for Himself

Yocheved Lavon

I had the privilege of translating Rabbi Grylak’s “Point of View” columns from Hebrew to English for over 15 years. When I say privilege, it is no empty cliché. Oh, it was a hard job, especially because I usually received the columns on Sunday mornings, hours before the deadline, and as Rabbi Grylak’s prose didn’t lend itself so easily to translation, it took every ounce of my ability. And that is just one reason why it was a privilege.

Once, when I was the guest of the former literary editor of another Jewish magazine, he remarked to me, “Rabbi Grylak doesn’t just parrot the party line, does he?”

“No,” I answered. “He thinks for himself.”

What my host meant was that Rabbi Grylak was his own man, speaking from his own conscience and his own heart, a conscience and a heart that were infused with the Torah he learned and the influence of his many teachers, but always himself and never an empty mouthpiece for slogans from the chareidi street.

My host nodded. “He thinks for himself,” he agreed.

Rabbi Grylak quoted gedolim, of course. Usually, his sources were his own encounters with great talmidei chachamim or with their seforim. That was the thing — they were his own encounters, processed through his own mind, and what emerged was pure Rabbi Grylak.

As I write, I’m still in shock, the morning after his petirah. And once again, a tight deadline is looming. Before I sat down to write, I davened for a core idea for this piece, and it came to me as the word paz, the gematria of Rabbi Grylak’s 87 years. Don’t cringe. I won’t turn that into a corny platitude, the antithesis of what he was all about.

Paz is refined gold. In addition to being a talmid chacham, Rabbi Grylak was well-read in history and current events, and all that knowledge was incorporated into who he was, and filtered through a mind that thought for itself. The refined gold that emerged was a product of self-realization in the best sense of the term. He gave all he had, and didn’t pretend to be what he wasn’t.

He was tough, warm, genuine, and straightforward. He knew how to show appreciation. Now and then he would email me to let me know that on his travels he had met people who hadn’t previously realized he was Israeli and expressed admiration for his command of English, and he hadn’t failed to give credit to his translator.

He was a good sport. Once, when I wrote a spoof of his column for a Purim issue of Mishpacha, he demanded that the English-speaking editors explain to him what was so funny, and when he finally understood, he agreed to let it be published and emailed to compliment me on it.

But he made one condition: The graphic designers had to make it obvious that he had not written the piece. Because he thought for himself.

Yocheved Lavon is a freelance editor and translator.

My Dear Friend

Rabbi Yehuda Heimowitz

Shortly after I met Rabbi Grylak, he took to calling me, “Yedidi hatza’ir (my young friend).” Frankly, I felt wholly undeserving of the title “friend,” but it was obvious that he meant it.

Here was a man who had escaped the Holocaust, learned under gedolei hador who molded him and imprinted upon him the worldview that he would share with his readership for nearly five decades, led the way as one of the very first stars of the kiruv rechokim movement, among so many other accomplishments — and more than seven decades into that illustrious life, he was addressing me, with all seriousness, as yedidi hatza’ir.

You could sit with Rabbi Grylak for hours without uttering a word, just listening to him recounting his memories and the incredible insights he gleaned from daily interactions with gedolim. He was a master raconteur, with a twinkle in his eyes and a wry smile almost permanently on his lips, so you could sense the witty conclusion coming even before it was out of his mouth.

But with all of his humor and wit, he took his role as editor in chief deadly seriously.

At our very first meeting, he shared the ethos behind Mishpacha Magazine. “People think that we address difficult issues facing our community just to be controversial. The truth is that we only raise issues that have been swept under the rug for years when we feel that the only way to improve the situation is by raising awareness.”

But he didn’t want to limit his influence to behind-the-scenes guidance of the editorial board of the English Mishpacha. It was important to him to share his wisdom with the broader public in his weekly columns, and he wanted to make sure that his message would resonate with all of the readers. In his typical humility, every so often he would make his way over to our side of the office to “consult” about how a column might be perceived by the English reading audience — as though he needed my opinion.

The word irreplaceable is sometimes overused, but there are people who truly cannot be replaced, because their accomplishments were not merely a product of talent — although finding someone with his writing talent alone would be difficult — but of the people they were, as a composite of their life experiences.

The Yiddishkeit Rabbi Grylak presented to the public was a beautiful tapestry, threads of the warmth and understanding of his chassidic roots interwoven with the analytical brilliance he absorbed in Kol Torah and Ponevezh upon reaching Eretz Yisrael after the war — all adapted to current events and to the current generation.

No one has lived the life Rabbi Grylak did, and all that’s left to say — paraphrasing, quite abashedly, the title he chose for me — is: Yedidi hagadol, mi yiten tmurosecha?

Rabbi Yehuda Heimowitz is a writer and editor who served as former Deputy Editor at Mishpacha.

"He was a chassid at heart." Sharing a light moment with David Damen

The Father of Our Mishpacha

David Damen

“DO you know how to write?” Rabbi Grylak asked me on the phone.

“I think so,” I answered modestly.

“So write it yourself, and we’ll fix it up if necessary,” he instructed.

That’s how it began, perhaps more than 20 years ago. I knew a Jew in Antwerp who had survived the Air France hijacking to Entebbe, and I called Rabbi Grylak to see if he was interested in the story. I asked him to assign the story to a professional writer, but he suggested that I write it myself. I began to write, and I haven’t stopped since. The magazine then was not what you are holding in your hand. There were no additional sections at all. No one even dreamed then of an English edition. We were a small, homogenous “mishpachah,” and Rabbi Grylak was the father of us all, the heart of the paper. The mentor and the instructor for all of us on how to write in a Jewish, professional and original fashion.

More than he was a gifted writer, he was a man of hashkafah. He had a clear Jewish hashkafah about our lives, and he didn’t hesitate to be critical when necessary. He wasn’t the establishment writer. Deep inside this exceptional person burned a revolutionary desire to change, to improve, to bring us all to a maximum self-awareness.

Rabbi Grylak was among the pioneers of independent writing in the chareidi media. He was very well-known. His articles were widely read, with great interest. His books were swallowed up by the readers. But Rabbi Grylak always remained modest and humble: A mensch with every fiber of his being. A convivial conversationalist. A friendly personality.

I spent lots of time speaking to him on a personal level. Whenever I visited Mishpacha’s Israel offices, I found myself in his office, and I waited politely for him to lift his eyes from his computer and say to me, in his rich Yiddish, “Nu, Duvid, vos machst du?”

He loved to talk to me in his polished Polish Yiddish, one of his childhood languages. He enjoyed speaking about chassidim, which reminded him of the chassidic home in which he was raised. He had a chassidic soul. He could quote the Sfas Emes and the Tzidkas Hatzaddik, and admired chassidim, who were groundbreakers in so many ways. He especially liked the originality and the wise and realistic views of my rebbe, the Belzer Rebbe shlita. For a time, he even wrote in the chassidus’s Hamachaneh Hachareidi newspaper.

I merited to have a special chemistry with him. He was very fond of me. His family knew about it as well, and a few years ago, they urged me to write their father’s memoirs. I even met with him to work out the framework for the job. But his health took a turn for the worse, and it became impossible. I deeply regret that. He was a treasure trove of thousands of memories of gedolim of the previous generation. He spent hours in conversation with Rav Shach, and with so many other gedolim of his time, from whom he imbibed the principles of hashkafah that he then spent the rest of his life disseminating. His work in hasbarah and for various kiruv movements showcased his ability to present Yiddishkeit in a contemporary language, and became a catalyst for many fascinating stories.

Writing was the joy of his life. Until the last minute when he was able, he did not stop typing. He knew several languages, and he made good use of them. Over the years, the magazine grew, sections were added, editors were recruited, and many, many employees joined the enterprise. And throughout it all, Rabbi Grylak remained the centerpiece of it all. The inspiration for all of us. The void that he leaves is painful and gaping.

Yehi zichro baruch.

“Every writer needs an editor – even I do.” Rabbi Grylak was an early mentor of Eliezer Shulman

Writing Lessons

Eliezer Shulman

Twenty-nine years have passed since that day I arrived, as a young and energetic bochur, to Mishpacha’s offices. I had come for a meeting with the paper’s editor, Rabbi Moshe Grylak. A few days earlier, I’d sent him a few articles that I’d written, and asked to be considered as a staff writer. I was very excited to be invited for an interview.

As soon as I entered his office, he noticed how nervous I was, and so he began with some small talk. By the time we got to talking about the articles, I was calm. With great skill, he pointed out the good parts of my writing, and the parts that needed improvement. “In every article, look for the angle that is less known, the chiddush on the subject. Remember, you’re battling for the heart of the reader. There are other articles that he can read. Think about which words will persuade him to read specifically your article on this subject, and not an article on a different topic.” Then he shook my hand and said, “Good luck to you.”

I walked out on a high and returned with a list of potential subjects for articles. He quickly scanned my list: “Very nice,” he said. “Is it okay if we speak about these subjects in the evening?”

That evening, I came back and found him deeply immersed in writing. “Welcome,” he said with a smile as soon as he noticed me. He pulled my paper with the list out of a whole stack of papers on his desk, and began to break them down into practical terms. Most of the subjects could not be turned into articles, he explained. There were two potentially suitable topics, but he asked me to first verify their suitability with a few people. Then, with great patience, he guided me in how to turn the subject into an article.

It was an unbelievable writing lesson. At one point, I took a pen and began to write down his requests (“these are not instructions,” he said).

Three days passed before I returned with an article. He read it with interest, expressed satisfaction with the writing, and said, “It will be in the paper next week, b’ezras Hashem.”

A week later, I excitedly opened the paper and found my name on an article that had been significantly altered. Tearfully, I approached him in his office. He looked at me in surprise. “What happened?” he asked, and handed me a tissue.

“Was it written so badly?” I asked.

“It was written well,” he replied.

“So why so many changes?” I wondered.

“There’s writing and then there’s editing, which is a craft in and of itself,” he replied. “You write well and you have potential. Every writer needs an editor. I also give my columns to an editor to work on. A person cannot see his own flaws,” he explained.

Then he added, “Now start working on the next article.”

Eliezer Shulman is a Deputy Editor at the Hebrew Mishpacha.

A sense of cohesiveness united all his disparate activities

Ascending with the Auleh

Gedalia Guttentag

“This hand merited to pull Nathan Birnbaum’s beard!” were practically the first words that Rav Moshe Grylak greeted me with, a rookie journalist, when I first stepped into Mishpacha.

Delivered with the trademark twinkle in his eye, the pronouncement would have been incomprehensible to anyone else, but meant the world to me.

It was a reference to my great-great-grandfather, the legendary baal teshuvah of the early 20th century who founded Zionism, then secular Yiddishism, and lastly Agudas Yisrael.

While the memory of Dr. Birnbaum, who passed away in 1937, has faded across large sections of the frum world, Rabbi Grylak was likely the last person alive — besides my own grandmother — to have met the man himself.

Toddler as he was at the time, he didn’t remember anything from the encounter. But his father — a close member of Dr. Birnbaum’s inner circle during the latter’s final years in Holland — had conveyed the impression of his mentor in such detail that Rabbi Grylak was, in a sense, a talmid of the prewar leader.

So, there he sat in his small office in Mishpacha’s old HQ in Jerusalem’s Har Hotzvim, singing the hymn of the “Aulim,” the movement dedicated to the spiritual revitalization of the Torah world that was Nathan Birnbaum’s last contribution to communal life.

And although Rabbi Grylak had many great teachers, from the Chazon Ish to Rav Shach, part of what made him a leader himself was the ever-present memory of Nathan Birnbaum.

Rav Moshe Grylak was the last of a generation of multifaceted Torah activists, big men whose careers spanned a dizzying array of enterprises. Like his friends, Degel HaTorah leader Rav Avraham Ravitz and Rav Yudke Paley, Rav Grilak was an ish eshkolos — a rav, kiruv pioneer, mechaber seforim, newspaper editor, and novelist.

His bonhomie, charm, and rapier wit were a byword, but like his numerous endeavors, there was a sense of coherence, of being part of a greater whole in his many disparate activities.

It was the same Rabbi Grylak who gave us seforim on hashkafah, and page-turners about the Mossad because he believed we needed kosher literature. Wearing one hat, he defended the chareidi cause in the secular Israeli public square, and donning the other, he would attack wrongdoing inside the frum world in the pages of Mishpacha, because that was the call of the hour.

That sense of consistency was possible only because to Rabbi Grylak they were truly all the same cause: a spiritual struggle on multiple fronts. The battle for those out in the cold being lost to the Jewish people, and for those inside the big Torah tent.

In that wide-angle view of Am Yisrael, the determination to wield the pen for eternal Jewish ideas, and a lifetime of striving ever upward, it was possible to detect the fingerprints of the man on whose lap he’d sat all those years ago — the great “Auleh” himself.

Gedalia Guttentag is a Deputy Editor at Mishpacha.

“Why is this topic the main feature this week? How is it important to our readers — how does it impact their lives?” Rabbi Grylak had an unerring instinct for his craft

The World He Shaped

Nomee Shaingarten

“D

id you read this book?” Rabbi Grylak asked me one day, holding up a paperback edition of the iconic novel, The Spider’s Web.

It was a couple of months after I began working as the administrative assistant of the soon-to-be-launched English Mishpacha, and had already realized that the unassuming editor-in-chief whose office abutted my workspace was a fountain of wisdom borne of fascinating life experiences, and a master of the craft that our fledgling team was just beginning to learn, under his skillful guidance.

But I had no idea why he had this English-language novel among the piles of books on his desk, as I responded enthusiastically, “Did I read it? I know it by heart! Do you know what this book was? It was the first of its kind to be published in English, and we couldn’t get enough of it! Even my friends who never read, got through the whole thing and loved it!”

I carried on in this vein for a few minutes, until he remarked casually, “I wrote it.”

Whaaaat? I was shell-shocked, trying to align everything I’d learned about Rabbi Grylak over the past few weeks, with my perception of the person behind the pseudonym of the intricate thriller.

But after nearly two decades — and thousands of magazines shaped by his vision — it makes perfect sense. As is abundantly clear from the hespedim at his levayah, and the tributes written by his contemporaries, colleagues, and proteges, Rabbi Grylak contained multitudes.

He devoted his tremendous talents to a range of groundbreaking initiatives that were seemingly unrelated, yet he seamlessly integrated elements from each of them into everything he did. So The Spider’s Web was not only a literary masterpiece with ingenious plot twists and strategic thinking, it was also a work of mussar and emunah, and at the same time, a history lesson and a window into the complex world of the Holocaust survivor experience.

But what stands out most when I think of Rabbi Grylak and everything he accomplished, is his humility.

That winter day, when I stood star-struck facing the now-revealed literary hero of my youth, he responded warmly to my enthusiasm. He was so happy to hear that the book was well received in America; he hadn’t really had access to firsthand feedback until then. He peppered me with detailed questions: What did I enjoy? What did my friends discuss? How about my brothers, he was curious to hear if the boys read such a thick book, and if their opinions were the same as the girls….

I was young, and the book was over five years old at that point and a proven bestseller, but that did not stop him from asking my opinion about his work, with authentic interest to extract insights that he could keep in mind for his next effort.

This kind of conversation was echoed many times over the years, in different contexts. No matter that Rabbi Grylak was the undisputed master of the frum media world that he was so instrumental in shaping, and that he was the mentor from whom so many aspiring writers sought advice — he approached the whole enterprise of the English-language Mishpacha with the humility of a novice, perpetually curious about how the dynamics of the industry differed in the US.

He sought the input of his translators and editors on his weekly column, as well as his rare — but always exquisite — feature articles. He did not cut any corners professionally, and he viewed the added dimension of addressing the international readership as a welcome challenge.

Every new member of our editorial team was introduced to Rabbi Grylak as the veteran expert — and he shared his expertise generously. But he was quick to tell us all that any guidance, advice, or strategy he shared was only as valuable as our ability to apply it to our audience. His oft-repeated mantra was, “Love your reader” — that was the key to successful journalism.

And he loved his readers, each and every one. For many years, he read every letter to the editor and singled out the ones that raised valuable points that he felt should shape our policy going forward. He was particularly interested in the many readers who sent feedback to his column and took the time to personally respond to as many of them as he could, especially when he felt that a reader misunderstood his point and he wanted to clarify. He frequently approached me holding a copy of the latest issue of the magazine, flipping through the pages, and stopping at the articles that caught his interest: “Why is this topic the main feature this week? How is it important to our readers, how does it impact their lives?”

His intuition was always spot-on, even though the product was not in his native language. Although he was not fluent in English, he knew how to spot talent in English a mile away. When he succeeded in conveying to the people he tapped the ethos of the Mishpacha mission and the journalistic craft, he didn’t hesitate to assure them of his confidence that they would thrive. And he couldn’t have been prouder when they did.

The last time I saw Rabbi Grylak was at our Erev Pesach gathering, which was attended by over 150 employees of the Hebrew and English editions, in the expansive office that is worlds away from the small apartment-turned-office that Rabbi Grylak worked out of in the early days of Mishpacha three decades ago.

I approached him to wish him a good Yom Tov and refuah sheleimah, and in response he motioned toward the bustling scene around him, with all of the spirit that accompanies the completion of a Yom Tov issue, and the onset of a welcome break.

“Olam k’minhago noheg,” he said meaningfully. Loosely translated: “The world moves on.”

I tear up now, as I did then, and I hope he heard my response through all the surrounding noise: “Zeh haOlam Shelcha – it’s your world.”

You shaped it; you transformed it; and you gave us all the gift of your wisdom and insight with which we hope to continue your legacy.

Nomee Shaingarten is the Chief Content Strategist at Mishpacha.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 962)

Oops! We could not locate your form.