Once a King

| June 18, 2008Sassoon Abda is one hundred years old now, but the last four decades of his life have been a free gift. He was whisked away from the gallows at the last moment and survived years of torture at the hands of the evil Iraqi regime. The indictment of this former millionaire: serving as a Zionist spy.

He is one hundred years old, but you’d never suspect it. He finishes up the last prayers of Shacharis, carefully winding up his tefillin, before welcoming his guest into his sixth-floor Tel Aviv apartment. That Sassoon Avraham Abda overcame years of cruel, unspeakable torture at the hands of the Iraqi government after the Six Day War is another surprise. Sassoon’s seventy-one-year-old son, Eliyahu Abda, translates the incredible story of his father, who speaks only Arabic.

For many years in Baghdad, Sassoon, a Jewish real estate broker, was treated “like a king” by the prime minister and government officials alike. He was invited to important state events and was entrusted with the confidences of top officials because of his sincerity and uprightness, Eliyahu explains. Through his real estate dealings and the villas he built in Baghdad, he had succeeded in creating a small fortune which allowed his wife and five children to live in comfort. “We were half a Rothschild,” Eliyahu says. “My father made 90,000 dinar, which was like 3 million dollars.”

As history has it for Jews living in comfortable exile, the situation of the Jews in Baghdad took a deadly turn after the establishment of the State of Israel, and then again after the Six Day War in 1967. Jews were killed without reason, tortured, or falsely accused of plotting against the Iraqi government. At that time, the Ba’ath Party, under the chairmanship of Saddam Hussein, retook the power it had lost in 1963. It took another ten years before Saddam was officially named president, but he held the reins of power nonetheless.

Many of the abductions, tortures, imprisonments, and murders from this period are documented in the book Fascinating Life and Sensational Death — The Conditions in Iraq Before and After the Six Day War by Gourji Bekhor. The book includes a section devoted to the horror story of Sassoon and his brother Meir, Jewish victims of an evil regime.

On Friday. January 5th 1968, police knocked on the door of Sassoon’s newly-built villa and said that they were interested in asking him and his brother some questions and would return them home in five minutes. Those five minutes became nearly five years of torture. The brothers were imprisoned separately in the Iraqi Ministry of Defense, accused of being spies for America and Israel. There they were fiercely beaten for four days, and then they were moved to a torture prison, which began a year and four months of horrifying punishments, followed by three years of prison labor.

Sassoon laughs, recalling the moment of incarceration. “Meraglim! They thought we were spies.” The news of the brothers’ imprisonment reached Israel and, as Sassoon remembers, he found out that Golda Meir expressed publicly that “they are my brothers; they are not spies.”

Initially, the brothers were each placed in a solitary cell, one and a half meters in width, length, and height, with one blanket. They were kept there for seventy-two hours without food or water. Following this, they were moved to a normal cell, fed minimal amounts of food, not allowed to see other prisoners, and insulted and beaten constantly.

They were taken to the Muasker Al-Rashid military camp after four months and were sent bedding and other items by their families, who found certain channels to reach them. Here they were similarly served minimal amounts of food and beaten in their cells every two weeks. After seven more months, in December, they were moved to an underground cell where tortures continued, this time being beaten every six hours, day and night. One month later they were moved to upper level cells where their main torture — the position of which Eliyahu demonstrates — was being tied by their hands to a ceiling fan, which would then be turned on.

Only in May of 1969, four months later, were they called for interrogation, where again they were severely beaten. At one point Sassoon lost consciousness and Meir believed he was dead. Following were more unspeakable tortures followed by failed suicide attempts — one by Sassoon and six by Meir.

At last, three months later, the brothers were taken to the Revolutionary Court and instead of being sentenced to death by hanging, as many others had been, they were allowed two lawyers to defend them, which Eliyahu had helped to find for the family. The brothers were sentenced to three years in prison with hard labor. All of their newly built property was confiscated when they were finally released on January 11th 1971, and the brothers were left penniless and denied passport rights.

They were finally able to escape in July 1973 and made it to Israel via France. “We left Gehinnom,” Sassoon says.

Eliyahu recalls the initial eight months during which the family did not know where their father was and whether he was even still alive. The family began to live undercover; Eliyahu recalls not walking with a kippah in the streets, and not doing anything to demonstrate their Jewishness in public. However, the family continued to keep mitzvos in the home.

It wasn’t until Eliyahu saw a newspaper article about a group of spies that were imprisoned, his father included, that they knew what had happened to Sassoon, and that he was still alive. He told his mother he would search for a lawyer; meanwhile, they found various channels through which to send Sassoon and Meir food and provisions.

With great perseverance, Eliyahu went from lawyer to lawyer to find one that would agree to defend a Jew. Then, the idea came to him (Eliyahu believes he was divinely inspired) to look for a lawyer from the Ba’ath party, the Arab secular socialist party of which Saddam Hussein was already on the way to becoming the leader. A Ba’ath lawyer did indeed agree to take the case, but asked for a very large sum of money that the family did not have after Sassoon’s abduction.

In a most courageous act, Eliyahu’s strong-willed mother went with her sister-in-law, the wife of Meir Abda, to the home of Saddam Hussein himself to see if he could help find and release their innocent husbands. They spoke directly to both the wife and mother of Saddam Hussein, who explained to them that if anyone went against the government “even by a hair’s breadth” they would be killed. The visit did not, at least directly, contribute to the Abda brothers’ release.

Again, Eliyahu recalls, “G-d gave me a mind, and somehow I found money.” Though he only came up with half the requested price, a lawyer was procured and the case was brought to court. It was this court case that got Sassoon and Meir three years in prison as opposed to the sentence of death by hanging. “It was a miracle that they lived,” Eilyahu says. “G-d saved them from death.”

Eliyahu did not see his father immediately upon release, however. Soon after the court case, he and his wife were granted passports and they took that short window of opportunity to fly to Israel through Turkey.

In truth, Jews had been officially granted emigration rights by the Iraqi government in 1950, provided they relinquish their Iraqi citizenship, but thousands remained.

Eliyahu says that his mother felt the call to be one of these first people to leave Iraq and had told Sassoon early on that they should leave all of their possessions in Baghdad and move to Israel. “She always knew we had to leave, but he didn’t want to,” Eliyahu explains. “He thought he was a king!”

Iraq’s connection with the Jewish people began with Avraham Avinu and continued on after the Babylonian exile. Sassoon’s story is one of many that mark the tragic end of the Jews’ great exile in Iraq. At the time, Rabbi Sassoon Kahdouri served as Chief Rabbi and President of the Jewish Community in Iraq and passed away in 1971, which caused a further dissolution of the Jewish community in Iraq. Now, Eliyahu reports, there are only a handful of Jews living in Baghdad who took it upon themselves to take care of the once-thriving synagogue.

In Bekhor’s book, the caption under the photographs of a younger Sassoon and Meir Abda states simply: “The tortures inflicted on the two brothers are filled with horror beyond belief. Their survival was a miracle.” Sassoon found himself an older man in a new country, with a body that had sustained years of torture. He did not return to work in Israel, but rather spent his years at home, where family and friends continue to visit.

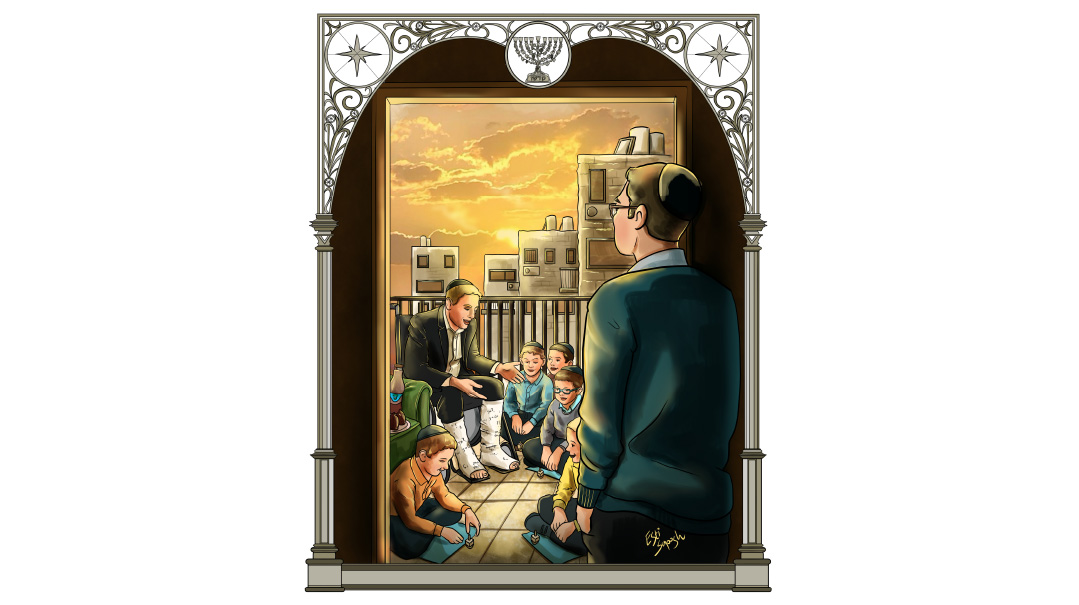

Sassoon Abda and his son Eliyahu live on the same street in Tel Aviv, finally able to express their Judaism and keep mitzvos without fear. Sassoon enjoys the company of his son, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, who visit from different cities in Israel and all over the world. A king once again, albeit with quite a different type of crown, this time in the Holy Land.

ZIONISTS OUT

In 1948, there were approximately 150,000 Jews in Iraq, but like most Arab League states, Iraq initially forbade the emigration of its Jews after the 1948 war, on the grounds that allowing them to go to Israel would strengthen the fledgling country. At the same time, increasing government oppression of the Jews fueled by anti-Israeli sentiment, together with public expressions of anti-Semitism, created an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty.

In March 1950, Iraq passed a law — to be in effect for one year — allowing Jews to emigrate on condition that they relinquish their Iraqi citizenship. Iraq apparently believed it would rid itself of those Jews it regarded as the most troublesome, especially the Zionists, but retain the wealthy minority who played an important part in the Iraqi economy. Israel mounted an operation called “Ezra and Nehemiah“ to bring as many of the Iraqi Jews as possible to Israel, and sent agents to Iraq to urge the Jews to register for immigration as soon as possible.

The initial rate of registration accelerated after a bomb injured three Jews at a cafe. Two months before the expiry of the law, by which time about 85,000 Jews had registered, a bomb at the Masuda Shemtov Synagogue killed several Jews and injured many. The law expired in March 1951, but was later extended after the Iraqi government froze and later appropriated the assets of departing Jews (including those who had already left). In 1951 the Iraqi Government passed legislation that made affiliation with Zionism a felony and ordered “the expulsion of Jews who refused to sign a statement of anti-Zionism. During the next few months, all but a few thousand of the remaining Jews registered for emigration, spurred on by a sequence of bombings that caused few casualties but had great psychological impact. In total, about 120,000 Jews left Iraq.

The remainder of Iraq’s Jews left over the next few decades, and had mostly gone by 1970. In 1969 eleven Jews were hanged, nine of them on January 27th in the public squares of Baghdad and Basra, accused of being spies for Israel. This was just weeks after Sassoon and Meir were taken prisoner, and was intended to be their fate as well. The 2,500-strong remnant of the community almost entirely fled shortly thereafter.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 213)

Oops! We could not locate your form.